Nitrate/Nitrite Toxicity

Clinical Assessment - Evaluation

Course: WB 2342

CE Original Date: December 5, 2013

CE Renewal Date: December 5, 2015

CE Expiration Date: December 5, 2017

Download Printer-Friendly version [PDF - 1.1 MB]

| Previous Section | Next Section |

Learning Objectives |

Upon completion of this section, you will be able to

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Introduction |

The evaluation of nitrate/nitrite-related health effects most often presents as a clinical evaluation of an infant with cyanosis. Symptomatic methemoglobinemia is generally less common in older children and adults. While systematically working through the differential diagnoses with special emphasis on airway, pulmonary and circulatory causes, appropriate supportive care tailored to the individual patient's clinical status should be provided. The differential diagnosis for cyanosis in an infant includes (by mechanism)

In an infant with no known cardiopulmonary disease, cyanosis that is unresponsive to oxygen therapy is most likely due to methemoglobinemia. Methemoglobinemia is a condition of excess oxidized "ferric" hemoglobin where the reducing systems to return hemoglobin to a ferrous state are overwhelmed, impaired, or lacking [Nelson and Hostetler 2003]. Causes of methemoglobinemia can be generally grouped into three categories: endogenous (i.e., related to diarrhea, systemic acidosis, infection); exogenous (i.e. medication or toxin-induced); and genetic (i.e., related to methemoglobin reductase enzyme system deficiency or structural variant of hemoglobin (HbM)) [Nelson and Hostetler 2003, Wright et al. 1999]. A high index of suspicion is the key to proper and timely diagnosis. Note that methemoglobinemia can also occur with subtle or no symptoms depending on the methemoglobin level. Methemoglobin occurs when methemoglobin comprises more than 1% of the hemoglobin [Flomenbaum et al. 2006; DeBaun et al. 2011; Fernandez-Frackelton and Bocock 2009; McDonagh et al. 2013]. This can occur when the methemoglobin reductase system is overwhelmed (acquired methemoglobinemia) or deficient (congenital methemoglobinemia) and when a structural hemoglobin variant (hemoglobin M) is present (congenital methemoglobinemia) [DeBaun et al. 2011]. Other forms of abnormal hemoglobin (dyshemoglobin) that also have an impaired ability to transport oxygen and carbon dioxide include carboxyhemoglobin and sulfhemoglobin. Therefore, carboxyhemoglobinemia and sulfhemoglobinemia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Cyanosis from inherited and acquired forms of methemoglobinemia may present differently depending on the developmental stage of the patient. This is due to developmental differences in amounts of adult (HbA) and fetal hemoglobin (HbF) present as well as the presence of other structural variants of hemoglobin [McKenzie 2010]. Infants with inherited methemoglobin reductase enzyme deficiencies may present with cyanosis and elevated levels of MetHb shortly after birth [DeBaun et al. 2011]. There are several variants of hereditary hemoglobin M (HbM). Alpha chain variants may present with cyanosis at birth, whereas those with beta chain variants may not show cyanosis until 4-6 months after birth [DeBaun et al. 2011]. Consideration should also be given to the fact that carbon monoxide poisoning doesn't produce cyanosis [Haymond et al. 2005]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Exposure History |

The evaluation of a patient with suspected nitrate or nitrite exposure includes a complete medical and exposure history [ATSDR 2008]. For information on taking a complete exposure history including questions to ask adults and children, see ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Taking an Exposure History https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=33&po=0 ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Taking a Pediatric Exposure History http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=26&po=0 Clues to potential nitrate or nitrite exposure are often obtained by questioning the patient or family about the following subset of topics

See Table 2 for a select list of methemoglobin (MetHb) inducers. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medical History |

Additional questions should be asked about the medical history including

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Physical Examination |

All cyanotic patients should be assessed for possible cardiac and lung disease including

A central chocolate-brown or slate-gray cyanosis that does not respond to administration of 100% oxygen is suggestive of methemoglobinemia [Wright et al. 1999; Rehman 2001; Bradberry 2003; Denshaw-Burke 2013; Steinhorn 2008; Skold et al. 2011]. In addition, the patient is often (but not always) less ill than one would expect from the severity of cyanosis [Bradberry 2003; Denshaw-Burke 2013]. On the other hand, infants with a large proportion of fetal hemoglobin may have severely reduced oxygenation before cyanosis appears clinically [Steinhorn 2008]. Physical examination should include special attention to the color of the skin and mucous membranes. In young infants, look for

Note that for best results, the physical exam should be performed on an appropriately warmed and calmed infant [Steinhorn 2008]. Gastroenteritis can increase the rates of production and absorption of nitrites in young infants and cause or aggravate methemoglobinemia [Nelson and Hostetler 2003]. If gastroenteritis is present–especially in infants–evaluate the patient for the possible presence of dehydration (i.e., poor skin turgor, sunken fontanel, dry mucous membranes) [Wright et al. 1999; Zorc and Kanic 2001; Nelson and Hostetler 2003]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fetal Hemoglobin (HbF) |

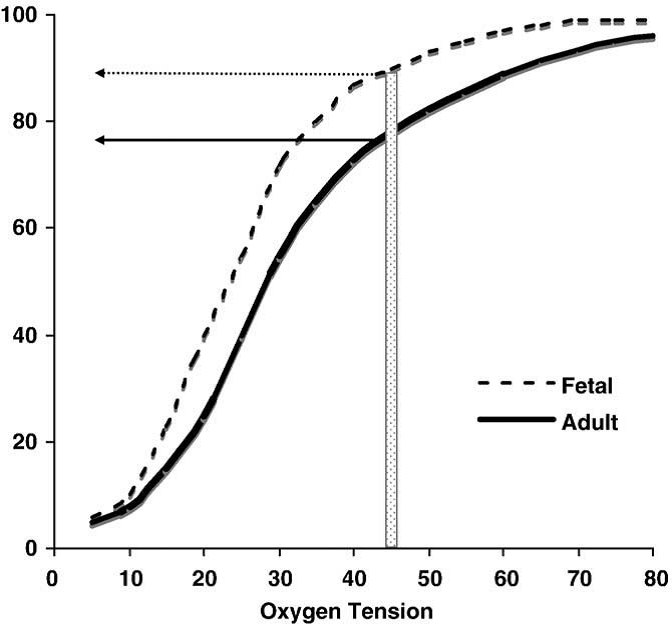

Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) is structurally different than normal adult hemoglobin (HbA). HbF is made up of two gamma and two alpha chains while adult hemoglobin (HbA) is made of two alpha and two beta chains. The level of fetal hemoglobin varies by developmental stage. The reference intervals by developmental stage include HbF: 90-95% before birth, 50-85% at birth, <2% at > 1 year to adult HbA: 10-40% at birth, > 95% at > 1 year to adult [McKenzie 2010]. The proportions of each hemoglobin will affect the oxygen saturation at a given PaO2. For example, if an infant has mostly adult hemoglobin and the PaO2 drops below 50 mmHg, a central cyanosis (arterial saturation 75-85%) can appear. If the infant has mostly fetal hemoglobin, a clinical cyanosis may not appear until the PaO2 drops below 40 mmHg. Therefore, infants with mostly fetal hemoglobin can have severe reductions in oxygenation before cyanosis appears clinically [Steinhorn 2008]. (See Figure 5.) In addition, because most clinically relevant hemoglobinopathies involve beta chain alterations, having higher HbF levels will affect the timing of the clinical appearance of these conditions.  Figure 5. Representation of the different characteristics of oxygen binding in fetal vs. adult hemoglobin. The structural differences between fetal hemoglobin (HbF) and normal adult hemoglobin (HbA) result in HbF's leftward shift from the HbA dissociation curve. HbF has a higher affinity to bind oxygen at lower partial pressures. The transition from predominately HbF to predominately HbA varies by developmental stage. For example, at a PaO2 of 45 mmHg, an infant with more HbF than HbA may not show clinical cyanosis (typically seen at about 80% oxygen saturation) as would an adult or infant with higher amounts of HbA. Figure adapted from Steinhorn 2008. (Open access, public domain author manuscript in NIH public access PMC system). Table 2. Reported Inducers of Methemoglobinemia

*Can also induce sulfhemoglobinemia |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Correlation of Signs and Symptoms with MetHb Levels |

The signs and symptoms of methemoglobinemia listed in Table 3 can be roughly correlated with the percentage of total hemoglobin in the oxidized form (see "Clinical Assessment-Laboratory Tests"). Unfortunately, because methemoglobin (MetHb) is generally expressed as a percent of total hemoglobin, levels may not correspond with symptoms in some patients. For example, a patient with a MetHb level of 20% and total hemoglobin of 15 grams per deciliter (g/dL) still has 12 g/dL of functioning hemoglobin, whereas a patient with a MetHb level of 20% and total hemoglobin of 8 g/dL has only 6.4 g/dL of functioning hemoglobin. Anemia, acidosis, respiratory compromise, cardiovascular disease, sepsis or the presence of other abnormal hemoglobin species (i.e. carboxyhemoglobin, sulfhemoglobin, sickle hemoglobin (HbS) may make patients more symptomatic than expected for a given MetHb level [Wright et al. 1999; Ash-Bernal et al. 2004; Skold et al. 2011]. Due to the large excess capacity of the blood to carry oxygen, levels of MetHb up to 10% typically do not cause significant clinical signs in an otherwise healthy individual. Levels above 10% may result in cyanosis, weakness, and rapid pulse [Ash-Bernal et al. 2004; Hunter et al. 2011]. Patients with comorbidities that decrease oxygen transport or delivery may develop moderate to severe symptoms at much lower MetHb levels than a previously healthy patient [Hunter et al. 2011]. A chocolate-brown or slate-gray central cyanosis - involving the trunk and proximal portions of the limbs, as well as the distal extremities, mucous membranes, and lips - is one of the hallmarks of methemoglobinemia and can become noticeable at a concentration of 10%-15% of total hemoglobin [Mack 1982; Geffner et al. 1981; Wentworth et al. 1999; Skold et al. 2011]. Dyspnea and nausea occur at MetHb levels of above 30%, while lethargy and decreased consciousness occur as levels approach 55%. Higher levels may cause cardiac arrhythmias, circulatory failure, and neurological depression. Levels above 70% are often fatal [Coleman and Coleman 1996; Hunter et al. 2011; Skold et al. 2011]. Features of toxicity may develop over hours or even days [Bradberry 2003; Hunter et al. 2011]. Table 3. Signs and Symptoms of Methemoglobinemia

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key Points |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Progress Check |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Previous Section | Next Section |