Chapter 3: Obtaining Site Information

- (Section 3.1) What information is needed?

- (Section 3.2) How is information obtained?

- (Section 3.3) Identifying information gaps

- (Section 3.4) Documenting relevant information

- (Section 3.5) Recognizing confidentiality and privacy issues

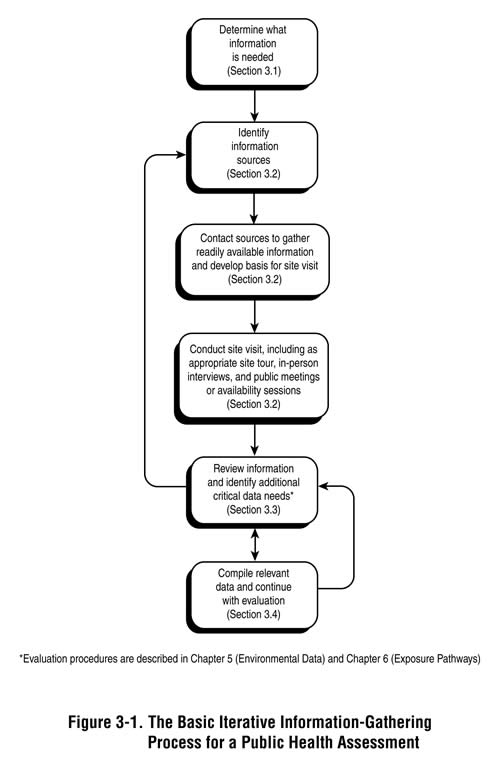

This chapter describes the information needed to conduct a public health assessment and how to obtain that information. Gathering pertinent site information requires a series of iterative steps. The process involves gaining a basic understanding of the site; identifying data needs and sources; conducting a site visit; communicating with community members and other stakeholders; critically reviewing site documentation; identifying data gaps; and compiling and organizing relevant data to support the assessment.

Data are collected throughout the public health assessment process to respond to community concerns (Chapter 4), support the exposure assessment (Chapters 5 and 6) and health effects evaluation (Chapters 7 and 8), and, ultimately, to draw public health conclusions with appropriate recommendations to prevent any harmful exposures (Chapter 9).

Figure 3-1 illustrates the basic information-gathering process. The following subsections detail the key components of this process:

As information is obtained, you will need to sort through it to identify what is most relevant for conducting the public health assessment. Each new source or set of information will likely cause you to refine your information search. In addition, you will need to identify possible information gaps and determine mechanisms to fill critical information needs.

3.1 What Information Is Needed?

This section describes the basic types of information you will look at when conducting a public health assessment and why each is important. You will not be collecting all this information at once. Rather, specific information needs will evolve as you learn more about the site and identify the issues requiring further study.

In general, you will need the following information:

- Site background information (including site operations and history, relevant regulatory actions, area land use and natural resources, tribal resource uses, presence of a tribal reservation or tribal land, and demographics).

- Community health concerns (including the nature of the concerns and the population[s] affected) and other community-supplied information, such as surveys.

- Environmental contamination information (including chemical and radiological data, as well as documentation, where possible, on the quality and reliability of the data).

- Exposure pathway information (including information on how people come in contact with contamination).

- Substance-specific information (including chemical and physical) properties that may affect a substance's fate in the environment or within the human body).

- Health effects data (including toxicologic, epidemiologic, medical, and health outcome data).

These types of information will support the evaluations described in the remaining chapters of this guidance manual and will enable you to develop a site conceptual model—a model of how people may or may not be coming into contact with site-related contaminants. Though it is better to err on the side of collecting more information than will ultimately be deemed useful, you will need to use professional judgment to determine the information most relevant to the assessment. Only those facts necessary to evaluate exposures and health implications should ultimately be considered and presented in the written public health assessment. Each piece of information should be collected with the intent of helping you evaluate whether site-specific conditions may be associated with exposures and if identified exposures might be associated with adverse health effects.

Site-specific circumstances will drive the amount of information that may be available. At some sites, such as Superfund sites under remediation, much documentation will exist. At other sites, background information and environmental data may be very limited. The more specific your knowledge about the site and its potential hazards, the more accurate and definitive your conclusions will be.

The checklist in Figure 3-2 summarizes general information to be considered by the health assessor. Not all the information described in this checklist is necessary to perform every public health assessment. On the other hand, for some sites, additional information may be needed. However, this checklist serves as a good starting point and guide. Appendix C provides another checklist that may be helpful throughout the public health assessment process; this "community check list" was developed by the Community/Tribal Subcommittee of ATSDR's Board of Scientific Counselors and expands upon some of the basic data needs presented in Figure 3-2.

Sections 3.1.1 through 3.1.6 discuss, in more detail, the type of information that should be considered in the public health assessment process. Section 3.2 describes the primary sources of this information and how to obtain it.

Figure 3-2. Basic Data Needs for Conducting a Public Health Assessment

|

Becoming familiar with the site, its setting, and its history is usually one of the first steps in the public health assessment process. Background information about the site is key to understanding the nature, magnitude, and extent of contamination. Background information also assists in identifying potentially exposed populations. This information will support detailed exposure evaluations to be conducted later in the assessment process.

The types of background information you will need include site description, site history and operations, regulatory history and activities, land use and natural resources information, and demographic information, as listed in Figure 3-2.

Obtaining descriptive information about key geographic and other physical features of the site lays the initial foundation for understanding potential associated exposures. A site description may include the following components:

- The site name and address or geographic location, including its relationship to entities such as towns and cities, and information on climatic and geologic conditions (e.g., floodplains, locations of major surface water bodies).

- The site boundaries, including any fenced areas. This allows on- and off-site areas to be delineated.

- The location of the site within the community, including a map showing the distance from the site to the closest residence or potential future residence. This will provide insight about the population potentially affected by the site.

- Visual representations of the site, such as site plans, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) quadrangle maps or other topographic maps, aerial photographs, and satellite images. Such visual tools may indicate the size of site operations, possible extent of surface contamination, conduits for and barriers to potential contaminant transport, and land use near the site, including distances to populations, schools, hospitals, and tribal lands near the site. If possible, collect global positioning system (GPS) data to support future site mapping.

- Any physical hazards (such as stacked drums, accessible chemical products, unexploded ordnance, pits, dams, dikes, and unsafe structures) at the site that may constitute a public health concern.

- Contact information (such as site representatives; local, state, tribal, and federal officials involved with site activities; community members).

3.1.1.2 Site Operations and History

Information about a site's current and past operations and historical development often indicates the types of contaminants that may be present, the possible extent of contamination, and the possible magnitude of human exposure. Obtaining information on the following aspects of site operations and history may be useful:

- The current and past activities conducted at a site, including process descriptions and associated wastes generated. These activities indicate the potential contaminants of concern at the site.

- Current and past hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal practices. These practices provide information on the potential for releases of contaminants to the environment.

- Dates of specific site operations. These dates indicate periods during which contaminant releases may have occurred, potentially influencing the extent of contamination and contaminant migration.

- Uses of the site (past, current, and planned future, if different), including all areas where the public or workers may be or could have been exposed to contaminants. This site usage provides information about exposure potential.

- Any significant events in the site's history (such as changes in site size/boundaries, site ownership, and development of the site, or fires, explosions, and other non-routine events) that may affect the types, rates, and times of contaminant releases.

3.1.1.3 Regulatory History and Activities

Certain (but not all) information about a site's regulatory history may assist you in evaluating a site's public health implications. You may have to sort through many regulatory documents, focusing on information in them that is relevant to public health exposures. For example, a detailed understanding of a site's permitting history may not be directly relevant to understanding site exposures, but a general understanding of the operational processes and types of regulated emissions/effluents permitted at a site may allow you to relate certain environmental contaminants to site operations. In addition, permit applications may provide useful information if limited historical data end up being available. Those activities associated with environmental releases, site investigations, and remedial actions will be most pertinent. Listing the names of all the site owners, for example, is not necessary when documenting regulatory history in the PHA. However, knowledge of different owners will help you understand site activities and processes as you are reviewing the site history.

Information about a site's past, current, and future regulatory status that may contribute to your understanding of the site's potential hazards includes:

- Information on the current Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) or Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) status of the site (e.g., is the site on EPA's National Priorities List [NPL], and why?).

- Results of any site investigations that have been conducted.

- Types of permits (air, water discharge, hazardous waste) held and compliance information and monitoring data available for the site.

- Actions taken by EPA, state agencies, or site operators to address contaminant releases from the site.

- Remedial activities and other risk management strategies implemented, planned, or proposed (including past, current, and future monitoring practices and/or institutional controls).

3.1.1.4 Land Use and Natural Resources Information

A review of land use and natural resources at and near a site provides valuable information about the types and frequency of the surrounding population's activities and the probability for human exposure. Land use in the area can affect the degree of contact with contaminated soil, water, air, waste materials, plants, and animals. (Guidance for evaluating site-specific exposures is provided in Chapter 5). Further, you will need information about past, current, and planned or proposed future land use to evaluate how site conditions and exposure scenarios may have changed or may change over time. Photographs (including aerial photographs) and maps indicating site conditions, proximity to populated areas, and area land uses are often helpful tools.

The following specific information may be useful:

- Site accessibility (including the presence, integrity, and suitability of warning signs, fences, gates, and other security measures, as well as any physical signs that people or animals have gained access to the site).

- Residential, commercial, and industrial land use on or near the site and the types and levels of activities (residential, recreational, and occupational) of potentially exposed populations. (Different types of activities can affect whether people are exposed and the frequency and duration of exposure).

- Schools (including daycare operations; elementary, middle, and high schools; children's athletic or recreational facilities).

- Other nearby industrial sites, including any CERCLA or RCRA sites, that may contribute to contamination and/or exposure.

- Waste and disposal sites such as landfills, surface impoundments and smaller sources of contamination (e.g., junk yards, gas stations, etc.) that do not necessarily represent industrial sites but can still contribute to contamination and/or exposure.

- Recreational uses of the site (such as dirt biking, camping, fishing, and hunting) and areas around or near the site (such as parks, playgrounds, and beaches).

- Planned or proposed future use of the site and proposed land transfers.

- Locations of public and private water supplies—including groundwater wells or surface water intakes (particularly hydraulically downgradient or downstream of the site) used on-site or off-site for drinking water, agriculture, or commercial purposes—and their distances from the site.

- Surface water use (e.g., swimming areas, boating areas, and commercial, sport, or subsistence fishing).

- Locations of any drainage systems (e.g., springs, creeks, drainage ditches) that may be conduits for contamination.

- Nearby agricultural areas (e.g., crops, orchards, gardens, feedlots, pastures, dairy farms, bee hives) and the market/consumption patterns for these foods (home, local, regional, commercial, or subsistence).

- Biota (plants and animals) potentially affected by the site (such as fish and game) and patterns of human consumption of these biota (e.g., tribal populations preparing and using food in traditional ways may experience increased exposure to contamination).

3.1.1.5 Demographic Information

Demographic information helps identify and define the size, characteristics, locations (distance and direction), and possible susceptibility of known populations related to the site. Demographic information alone does not define exposure. However, since demographic data sets do provide information on potentially exposed populations, they can provide important information for determining site-specific exposure pathways. Keep in mind that demographic data may be dated (e.g., the national census is conducted once every 10 years) and thus may not accurately reflect more recent changes in the numbers and/or types of populations in an area. Population estimates for certain areas may be available between census years, but the source and applicability of intercensal or postcensal data need to be reviewed prior to use.

The following demographic information should be collected:

- A description of residential populations residing near or on the site, as well as people who may be exposed at nearby businesses, schools, and recreational areas.

- The location and distance from the site or contaminated areas to nearby residents and the size of the population within a specific radius of the site.

- Information on age, gender distribution, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in the potentially affected community to assist in identifying susceptible or particularly vulnerable populations and assist in interpreting relevant health outcome data.

- Information on the stability or transient nature of the population (e.g., length of residency, age changes, etc.) which may require looking at older censuses/ demographics for past periods.

As a baseline, you should summarize the demographic information for the area within a default 1-mile radius around the site boundaries. Other distances may be more appropriate or applicable depending on site-specifics (e.g., where air dispersion of contaminants is the main issue at the site, wind patterns might be such that your radius should be smaller or larger than 1-mile, or, if surface water contamination is a concern and an area is particularly flat or sloped, your radius could change). More specific temporal and spatial descriptions should be collected whenever possible for likely exposure scenarios.

Section 3.2 and the resource list at the end of the chapter provide detailed information on how and where to obtain pertinent demographic data.

3.1.2 Community Health Concerns

Understanding community health concerns related to a site or environmental release is an important component of the public health assessment process and ATSDR's overall mission. Community health concerns, therefore, need to be investigated and understood to the greatest extent practical. It is important to gather this information early in the process.

The nature and degree of community concerns will vary from site to site. For example, at some sites residents may express great concern about excess cancers in their neighborhood; at other sites residents may simply be looking for assurances that site-related contamination is not affecting them.

Types of information to gather include:

- Records of environmental and health complaints made by the public, including documentation of when these concerns were voiced. Focus on obtaining information related to potential site-specific impacts on people's health or well-being.

- Information about actions taken by federal, state, or local agencies (such as health departments), and responsible parties in response to health concerns, complaints, or issues.

- Health and other information obtained through individual and community meetings or through community health studies.

- Information obtained on local environmental justice, tribal member concerns, or community interest groups and issues that may reflect unique cultural concerns.

- History of government involvement and community response to past involvement.

- Community expectations for ATSDR involvement.

Once you have identified a community health concern, try to determine how many people share the concern (by determining the frequency and number of complaints received by a local health department or community group, for example).

One of the primary means of gathering this information is through communications with the community during site visits (as discussed in Section 3.2.5 and Chapter 4). Methods for identifying and responding to community concerns, such as holding public meetings and responding to community concerns in PHAs and PHCs, are detailed in Chapter 4.

In addition to public health concerns, community members are usually good sources of information about human activities on or near the site, such as children's play areas, locations along streams frequented by children and fisherman, location of local "swimming holes," etc. Community members can often provide some historic information about sites that are not captured in government reports, such as frequency of flooding events when unplanned contaminant releases may have occurred (see example in box below) or frequency of site fires.

Example of the Value of Interviewing Community Members

During review of historical environmental data at a closed landfill site, a health assessor noted elevated (above background) levels of cadmium, lead, and other metals in a small pond across the road from the site. The pond had no known drainage connection to the landfill. In interviewing residents living adjacent to the landfill, the health assessor learned of the effects of heavy rainfall on the storm water flow pattern from the site during the landfill operating period. According to residents, during high rainfall events, storm water would flow from the landfill, across their yards, across the road, and into the pond. Residents reported storm water depositing mud and other debris in their yards and the street. As a result of this information, the health assessor recommended surface soil sampling of the affected residential yards, connected the contamination of the pond to the landfill, and identified an exposure point that might not have otherwise been evaluated.

3.1.3 Environmental Contamination Information

Environmental contamination data enable you to evaluate the nature and extent of environmental contamination and the magnitude of potential exposures. Environmental contamination data will provide you with the information needed to answer questions about: to what contaminants people might be/have been exposed; when and for how long people might be/have been exposed to the contaminants of concern; the likelihood of exposure to different levels of contaminants; and how reliable the data are on which you will base your conclusions. This information will be used with exposure and toxicologic data to evaluate possible health implications of exposures. Efforts should focus on obtaining as extensive a data set as possible for those media for which past, current, or potential future exposures exist.

The following type of information should be obtained for each contaminated medium (i.e., groundwater, soil, surface water, sediment, air, and/or food chain [biota]):

- The specific substances identified at and near the site (on-site and off-site sampling data).

- The concentrations of the substances found, including naturally occurring background conditions (e.g., metals in soil).

- The location and sample depth (i.e., 3-dimensional location) where the substances were found (including maps, where possible).

- The dates when the samples were collected.

- Sampling collection and analysis methods used, including detection limits.

- Field measurements, such as conductivity and field pH (as opposed to laboratory pH, field pH measurements of monitoring wells and water supply wells often yield important information on how representative and useful the particular water sample at a given location may be).

- Quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) data, to ensure that the resulting data are adequate for assessing possible human exposures (i.e., that the data are of sufficient quality and are representative of area contamination). More extensive information on desirable QA/QC procedures is presented in Chapter 5.

Table 3-1 provides an overview of the key information on environmental contamination that you should gather. ATSDR's guidance manual entitled Environmental Data Needed for Public Health Assessments (ATSDR 1994) provides more in-depth guidance on specific data needs. If necessary information is not available, you should take into account any assumptions you end up making in your evaluation, and will need to qualify your evaluation as appropriate when presenting it in the PHA.

Table 3-1. Contamination Information Needed by Environmental Medium*

| Environmental Medium | Type of Information To Collect |

|---|---|

| Groundwater |

|

| Surface water/sediment |

|

| Soil |

|

| Air (ambient, stack, soil gas, indoor air, and dust) |

|

| Food chain (biota) |

|

| Physical hazards |

|

| Radiologic parameters |

|

Source: ATSDR 1994.

*Chapters 5 and 6 discuss how this information is used in the public health assessment process.

In some cases, estimated or calculated environmental data obtained from models may be the only available information (e.g., air concentrations estimated from air dispersion models). Although environmental measurements (sampling data) are always preferred to estimated and calculated numbers (modeled data), modeling data should be examined if they provide additional perspective on site-related conditions. In such cases, you should obtain information about the assumptions used in and uncertainties of the model as well as information about the quality of any computer models used. Chapters 5 discusses how environmental and modeled data are evaluated in the public health assessment process and where and how this information is presented in the PHA.

Environmental data may be available in many different forms (e.g., laboratory reports, summary tables, CD-ROMs, microfiche, or databases). Obtaining environmental sampling data electronically can save you much time because you can often analyze the electronic data in spreadsheets, import the data into geographic information system (GIS) formats, and so on without having to manually enter the data. Such data are often available from EPA and other government agencies or their contractors, or site owners and their contractors.

3.1.4 Exposure Pathway Information

Because adverse health impacts can only occur if people are exposed to contaminants, much of the information you seek should ultimately address some aspect of an exposure assessment, such as contamination sources, contaminant fate and transport, affected environmental media (i.e., water, soil, air, food chain [biota]), exposure points, exposure routes, and potentially exposed populations—elements of a completed exposure pathway. Much of the information about sources, affected media, and exposure points and populations can be gathered through the review of site background information discussed above. However, exposure routes (how contaminants get from a source to a potentially exposed population) are influenced, if not dictated, by the fate and transport of contaminants in the environment. Additional site-specific information that you may need to evaluate contaminant fate and transport includes local geologic, topographic, and climatic conditions. (Methods for evaluating exposure pathway information are detailed in Chapter 6.)

Fate- and transport-related information varies somewhat from one medium to another and may include the following:

- Topography, the relative steepness of slopes and elevation of the site, may affect the direction and rate of water runoff, rate of soil erosion, and potential for flooding.

- Soil types and locations (e.g., sandy, organic) influence percolation, groundwater recharge, contaminant release, and transport rates.

- Ground cover/vegetation of the site greatly influences the rates of rainwater infiltration and evaporation and soil erosion, as well as the accessibility of contaminants to people.

- Local climate conditions, such as annual precipitation, affect the amount of moisture contained in the soil and the amount of percolation, as well as the water runoff and groundwater recharge rates. Temperature conditions affect rates of contaminant volatilization and the frequency of outdoor human activity.

- Meteorologic factors, such as wind speed, may influence dispersion and volatilization of airborne contaminants and soil erosion rates.

- Groundwater hydrology (e.g., depth, direction, and type of flow) and geologic composition affect the direction and extent of contaminant transport in groundwater.

- Locations of surface-water bodies and planned and unplanned use of those water bodies may significantly affect the migration of contaminants off the site and into other media.

- Frequency of flooding events may significantly affect the migration of contaminants off the site and into other media (see the box in Section 3.1.2).

Table 3-2 lists the types of contaminant transport information you may need to collect for each environmental medium.

Table 3-2. Site-Specific Information That May Be Needed To Evaluate Contaminant Fate and Transport*

| Environmental Medium | Type of Information |

|---|---|

| Groundwater |

|

| Surface water/sediment |

|

| Soil |

|

| Air |

|

| Food chain/biota (plants, animals) |

|

| Waste materials (e.g., exposed wastes, liquids, drums, mine tailings) |

|

*Chapter 5 describes when this type of information may be needed and how it is used in the public health assessment process.

Health outcome data can provide information on various aspects of the health of people living on or near a site. It may reveal whether people living or working near a site are experiencing adverse health effects at a rate higher than would be expected to occur. Health outcome data can constitute a key source of information for conducting public health assessments. However, site-specific health outcome data are rarely available or of sufficient quality to enable you to link health outcomes with site-related exposures. Whether you should evaluate health outcome data depends on a number of factors. The criteria for deciding whether and what health outcome data should be obtained are discussed in Chapter 8.

Health outcome data that may be obtained can include:

- Morbidity data (e.g., incidence of cancer, birth defects, or other diseases from state or county disease registries).

- Mortality data (e.g., death certificates).

- Disease information from community health records, healthcare provider agencies, and individuals (e.g., community health centers, private physicians).

- Health statistics from community health studies.

When examining health outcome data, it is important to also obtain information about the source and type of information, relevance to the populations of concern at the site, and a possible contact person for each study, in addition to the study findings. Remember, health outcome data will not prove cause and effect. Cause and effect may be addressed through long-range epidemiologic studies.

In consultation with an epidemiologist, you need to determine the extent to which health outcome data can help support or refute public health conclusions (see Chapter 8). Health outcome data may point to the need for additional, focused environmental or health effects data collection, as in an exposure investigation.

3.1.6 Substance-Specific Information

The need for information on specific substances may be identified as you move through the public health assessment process. Once you have reviewed the site-specific information and gained an understanding of what hazardous substances are present and of potential concern, you may seek information on substance-specific properties to support your exposure pathway analysis and health effects evaluations.

Specifically, you may need the following:

- General information on the chemical and physical properties of environmental contaminants within the media of concern.

- Substance-specific toxicologic and epidemiologic data.

- General substance-specific biologic and physiologic data.

With the support of toxicologists, epidemiologists, hydrologists, and/or other specialists on your team, this information will help you more fully evaluate the nature and extent of contamination and the likelihood of adverse health effects. The specific type and sources of these types of data are detailed in Chapters 6 and 8. ATSDR's Toxicological Profiles can provide much of this information and are therefore a good starting point.

3.2 How Is Information Obtained?

ATSDR relies largely on information and environmental data already collected as part of regulatory investigations in its public health assessments. Information sources include government agencies, on-line resources, the community, and site owners and responsible parties, as discussed below.

Once you gain a basic understanding of the site, its history, regulatory status, and environmental health issues, you will need to identify and communicate with site-specific contacts in an effort to obtain data to conduct a public health evaluation.

Primary sources or mechanisms through which site-specific information can be obtained include:

- Health and environmental agencies.

- Internet resources (e.g., for background information, maps, demographic data, health outcome data, published literature).

- Community members and other stakeholders (e.g., petitioners, nearby residents, community groups or tribal members).

- Site owners and "potentially responsible parties" (PRPs), including their contractors.

- Site visit (e.g., for visual observations and personal communications).

The site visit, typically conducted early in the public health assessment process, should be viewed as a prime opportunity for meeting with the local community and gathering pertinent site information (see Section 3.2.5).

Government agency staff and documents are a primary source of site-related information and other materials that may support the public health assessment process. This includes federal, state, local, and tribal agencies that regulate site operations and oversee or conduct environmental or health investigations or monitoring. Governmental organizations that maintain databases of relevant environmental or health data also may be a good primary source of information.

These agencies also may assist in other ways, such as identifying local contacts (including additional stakeholders and elected or appointed officials), participating in site visits, reviewing draft documents, posting notices of public meetings to be held, providing information on community networks, and sharing mailing lists.

For example, EPA oversees many hazardous waste sites, including NPL and RCRA sites. In such cases, the EPA Remedial Project Manager, On Scene Coordinator (for sites in the removal program), and community relations staff can be a valuable resource for:

- Providing site background and status information.

- Providing the site's Administrative Record, which contains a listing of all site-related documents.

- Identifying community contacts and existing information distribution channels.

- Developing a plan for joint public meetings and communication mechanisms.

- Responding to community requests for information.

- Minimizing the release of conflicting information to the public. When multiple agencies are involved, the agencies should communicate with each other to help ensure that information released to the public from different agencies does not conflict or cause confusion.

Similar information may be available from state agencies involved with a site.

Table 3-3 lists various agencies and the types of site information they may be able to provide. Table 3-4 lists some of the types of documentation that may contain relevant data for the public health assessment which are available through government agencies.

Table 3-3. Information Available Through Government Agencies

| Agency | Possible Information |

| Federal Agencies: | |

| ATSDR Regional Representatives | ATSDR and EPA site files; names of state, local, and tribal contacts. |

| EPA Superfund/CERCLA Program | Site history; community concerns and community involvement activities; environmental monitoring data; any remedial activities; contact names for other agencies and possibly community members. |

| EPA RCRA Program | Site history; RCRA permit information; community concerns and community involvement activities; environmental monitoring data; any remedial or corrective actions; contact names for other agencies and possibly community members. |

| U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) |

Site history; environmental monitoring data; restoration program activities; cleanup schedules; future land uses. |

| Indian Health Service (IHS) | Tribal concerns/IHS environmental health programs in the site area. |

| Tribal governments | Specific tribal concerns related to the site. |

| Fish and Wildlife Service | Natural resource uses and possibly food chain (biota) concerns. |

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) | Climatic information (e.g., wind direction, rainfall). |

| Soil Conservation Service (SCS) | Soil information (e.g., soil types, erosion); regional agricultural pesticide use. |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture | Soil information; regional agricultural practices. |

| U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) | Geologic and hydrologic information (e.g., contour maps, well locations, topographic maps). |

| U.S. Department of Commerce | Maps and census data for the area around the site (available as Summary Tape Files or Internet). |

| State Agencies: | |

| Health Department | Reported health concerns; health outcome data; public meeting records; names of local contacts. |

| Environmental | Reported contaminant releases; environmental monitoring data; specific concerns at and near the site; information on ongoing/planned remedial actions. |

| Emergency response | Reported historic or chronic releases from the site and surrounding industries. |

| Local and County Agencies: | |

| Health department, hospitals, clinics | Health concerns or complaints; available disease/cancer registries or disease clusters in the area. |

| Water department | Location and depth of municipal supply wells (current and historical); compliance monitoring results; private well location and use; location of surface water intakes; types of treatment systems in place, currently and historically. |

| Library | City directories with names and addresses of residents who live or may live near a site; collections of historical information about a site/company, especially if the company was a major employer in the area. Also, libraries often serve as information repositories for site investigation reports, etc. |

| Planners | Demographic information; past, present, future development. |

| Environmental | Contamination concerns or complaints; environmental monitoring data. |

| Local game wardens | Fishing and hunting activities. |

| Extension services | Information on local soil conditions, plants. |

Table 3-4. Useful Government Sources of Information

|

|

1 TRI can sometimes provide supplemental information about contamination found in on- or off-site environmental media and may suggest additional sampling needs, though there are limitations to its usefulness. TRI includes information on: the annual amount of estimated releases of more than 300 selected toxic chemicals into the environment (reported by air, water, and land) by specific facilities; the types of chemicals that each listed company manufactures, processes, or otherwise uses; and the amounts of chemicals stored on site and/or transferred to waste sites. Several limitations of TRI data should be noted, including: reported releases are only estimates provided by facilities to EPA; data are reported on a volume basis and do not reflect concentrations of chemicals in environmental media; chemical releases are reported only since 1987 (when TRI was initiated); only certain chemicals are included; and only certain facilities (manufacturing and federal facilities with more than 10 full-time employees) are required to report releases to the TRI.

Internet resources may be particularly helpful in the early stages of the information collection process. Information often can be obtained more easily and quickly from the Internet than from traditional sources. Examples of available Internet information include Superfund site summaries, databases (e.g., census data and EPA's Toxics Release Inventory), and site maps. A more extensive listing of Internet resources is provided at the end of this chapter.

Keep in mind that anyone can post information on the Web, and that not all posted information is reliable. Therefore, be sure to pay close attention to the sources of all information obtained from the Internet, as well as all other sources, and assess their reliability.

3.2.3 Community Members and Other Stakeholders

The community associated with a site can be broadly defined as the population living on and around the site. Community members and community-based organizations are excellent sources of information about the site and about community health concerns (including site-specific issues, the nature of the concerns, local behavioral patterns that may influence exposure, and the degree to which the community is involved).

Working with the community involvement specialists or health educators on your team, as well as the regional representative, you can often initially identify a few key individual community or organization contacts by reading through government site files and/or talking with staff from different government agencies. These community contacts can often suggest additional people in the community whom you could contact. Some of the individuals and community groups that you might want to contact include (but are not limited to):

- Individual site petitioner(s) (if any) and/or local residents, particularly community leaders.

- Site-specific advisory boards.

- Tribal organizations/leaders.

- Religious organizations.

- Local medical society and other healthcare providers.

- Fishing, hunting, agricultural, conservation, and industrial organizations.

- Media (print, electronic).

- Community organizations.

- Local community environmental groups.

- Staff at universities or other area academic institutions.

- School principals and school nurses.

- Labor unions.

- Staff of local institutions and facilities near the site (e.g., child-care centers, prisons).

You should request meetings with some of these community members during your site visit to learn more about community concerns. These community contacts often can provide you with valuable information about the site, ways to obtain site data, the level of community interest, and the best strategies for interacting with the community. You can begin determining the types and extent of concern within a community by noting the nature and number of questions that residents ask. Again, work with health communication specialists to facilitate your interactions with the community.

You may also want to review local/community newspapers, including on-line archives, to identify historical information and health concerns. These sources might fill some information gaps in available site records.

Developing an open relationship with site representatives, including site owners, PRPs, and their contractors is very important. You should brief all site representatives or their designated contractors on ATSDR's role to gain their cooperation in obtaining needed site information. Some documents listed in Table 3-4 may be obtained from site representatives.

At federal facilities or other large industrial facilities, possible contacts include representatives of the public affairs office; occupational medicine, industrial hygiene, or public health professionals; civil engineering and/or water department staff; natural resources and pest management staff; facility environmental engineers or remedial program managers; staff representing other environmental programs; housing office staff; historians; and people responsible for environmental or public health cases or issues. In addition, at federal facilities, coordination with a federal agency's principal point of contact is typically required. Procedures and protocol developed by ATSDR should be consulted and followed (for example, see ATSDR's, Memorandum of Understanding between ATSDR and the U.S. Department of Defense).

3.2.5 Conducting the Site Visit

A site visit is an invaluable piece of the public health assessment process. The site visit provides you with an opportunity to:

- See the site to determine activities and possible exposure points.

- Identify current conditions at the site.

- Gather extensive information about the site.

- Meet with site representatives, state and local officials, tribes, community members, and other sources of information (e.g., local physicians or community leaders).

- Establish contacts to facilitate future information requests.

- Confirm previously gathered site information.

Site visits and regulatory reports often provide much of the necessary site background information. Meeting with members of the community and other contacts during the site visit is an important means of obtaining relevant documents and gathering additional information.

To prepare for the site visit, you should review any site-specific information you have gathered early on: site background information (including maps), community health concerns, relevant environmental and health outcome data, and demographics, noting what information has already been made available to the public about the site (e.g., TRI data, site-related reports, etc.). You should also review the types of information still needed and prepare a list of information needs and questions to pursue during your site visit.

Site visits are usually conducted by a small team including the health assessor, the regional representative, and a health communications specialist. The team makeup may vary, however, depending on site issues. Coordination is important to a successful site visit. Before the trip, you should meet with the other members of the site team and make arrangements to:

- Coordinate with the appropriate site or facility representatives to schedule site visit activities.

- Brief all contacts with whom the team will be meeting individually about the purpose of the visit.

- Send the contacts written confirmation of the site visit meeting dates, times, and places.

- Determine the type of meeting best suited for the community (public meeting, public availability session, and/or meetings with individuals) and arrange for the meeting(s) to be held during the site visit (see Chapter 4).

- Invite representatives of relevant agencies (EPA, state and local health and environmental departments, tribes) to appropriate meetings or visits.

- Develop informational materials (such as press releases and fact sheets) (see Chapter 4).

The health assessor/site-team leader should determine if it is necessary to enter any restricted areas (e.g., "hot zones"). If so, all participants in the site visit should make sure their health and safety training is up to date and that the required approval forms have been completed (e.g., safety check-off list, site health and safety plan, travel requisitions).

A tour of the site and its environs is an invaluable part of all site visits. Remember, the site visit is a critical component of your data collection activities. While touring the site, you should identify as much as possible any contamination source areas, the locations/proximity of private wells, physical hazards, warning signs or fences, potential exposure points (see example in box below), and approximate distances to places where people live and work. You should also ask the questions you prepared prior to the visit and collect any relevant documents and data sets.

Important Information Can Be Gained From Visual Examination of a Site

Examining the site area for signs of children playing is one of the more important reasons for a site scoping visit. For example, at one petitioned site, a health assessor observed children's toys in a drainage ditch connected to a wood treatment lagoon. Subsequent sampling of the drainage ditch and discussion with local parents revealed several local children had skin rashes and other problems that may have been related to playing in the drainage ditch where high levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were found in soil and water.

You are encouraged to take photographs during the site visit (with permission) and use a map to record the location and direction of physical features. Although physical hazards and any visible releases should be photographed or noted, be sure to use professional judgement to stay out of danger. All members of the site team attending the site visit are responsible for adhering to ATSDR and other applicable health and safety requirements.

During the site visit, you should also meet with community members, local and state officials, and tribal representatives as arranged prior to the visit. Again, you should come to these meetings prepared with questions and requests to obtain missing information, working closely with the health communication specialist on your team.

Document the findings of your site visit in detailed notes written during the visit. Field observations should be distinguished from information conveyed at meetings. Record concerns and issues accurately and objectively, without interpretation. List possible sources for additional needed data.

After conducting the site visit, you need to review and compile the information gathered. Consider a team debriefing meeting to evaluate information obtained during the site visit, define lessons learned, and begin developing site priorities and an action plan. See Section 3.4 for methods and tools for documenting and summarizing pertinent site information.

As with other steps in the information gathering process, you may identify additional data needs and may need to make additional contacts and possibly perform additional file reviews.

3.3 Identifying Information Gaps

Throughout the public health assessment process, you will continue to identify different types of information needed to support the assessment. As mentioned previously, data collection is an iterative process and will often require networking and follow-up inquiries.

As the process evolves and information needs are refined, you may find that some of the needed information simply does not exist. Health assessors are encouraged to use available information to the greatest extent possible in drawing public health conclusions. If there is missing or limited information, you should proceed by clearly identifying in your report (i.e., the PHA or PHC) what information is not known and how this lack of information may affect conclusions.

In some cases, you may believe that the missing information is significant in terms of assessing public health implications at the site, and may recommend that additional sampling or studies be performed to address the data gaps. If you find yourself in this situation, it is important to keep the public informed about the status of the public health assessment activities during the process.

Methods for evaluating the adequacy of the available information are described in the chapters that follow.

3.4 Documenting Relevant Information

Health assessors may benefit from using checklists when compiling site information. After you have collected as much of the needed information as possible about a site, the next step is to identify which information is most relevant to the public health assessment process and compile it in a meaningful way. For future reference, you may need to prepare a site visit report that lists all the people contacted during the trip; summarizes each meeting and its outcome; describes any environmental monitoring conducted; summarizes key site issues, important observations, and conclusions; and identifies remaining data gaps and other recommended actions.

Often the first step in organizing the information collected is to develop a Site Summary Table, as shown in Table 3-5, particularly for large sites where much information needs to be organized. For example, some Superfund sites and/or DOD and DOE sites might have numerous separate "areas of concern," each with different possible exposure situations and environmental conditions.

Compiling data in such a manner helps you sort out and organize the information collected and determine what is most important for assessing exposures and possible health hazards. After developing the Site Summary Table, you will be ready to begin a more in-depth evaluation of exposure pathways and environmental data, as described in Chapters 5 and 6.

Of utmost importance when documenting information is to clearly reference all information sources.

Table 3-5. Sample Site Summary Table

| Site | Site Description/Waste Disposal History | Investigation Results/Environmental Monitoring Results | Corrective Activities and/or Current Status | Exposure Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage Area #1 | 42-acre area located along the railroad yard in the northeastern portion of the site. Since 1942, incoming raw materials have been sorted here for distribution to the appropriate receiving facility. No hazardous wastes were produced here, but some of the incoming raw materials were classified as hazardous. The area is fenced. |

Groundwater: No volatile organic compounds (VOCs), semivolatile organic compounds (SVOCs) or inorganics were detected above health-based comparison values (CVs). Surface Soil: Arsenic (7.3 parts per million [ppm]) and iron (34,000 ppm) were detected above CVs. Soils naturally contain low levels of arsenic. Background concentrations range from 1 to 40 ppm with a 5 ppm average. Iron is an essential nutrient. |

A RCRA (Resource Conservation and Recovery Act) Feasibility Investigation (RFI) has been completed. Draft report recommends no further action. No further action planned. |

No past, current, or anticipated future use of groundwater in site area. Access to the area is restricted. No children or other trespassers likely to access area. |

| Former Fire Training/ Landfill Burn Area | Fire Training Area is a gravel pit 30 feet in diameter located northwest of the Main Test Area. Wastes were burned in this area approximately 20 times per year from 1973 to 1978. Liquids drain from the burn area via a pipe into a small pond to the west. |

Shallow Groundwater: The following VOCs were detected above CVs (maximum concentrations are in parentheses): TCE (680 ppb), PCE (15 ppb), 1,1-DCE (300 ppb). Cadmium detected slightly above background and its CV (44 ppb). Other metals detected at background levels and/or below CVs. Deep Groundwater: 1,1-DCE (150 ppb), methylene chloride (9 ppb) were detected above CVs in on-site wells. |

RFI is complete. Long-term monitoring of groundwater is ongoing. | Shallow groundwater is not used as a drinking water source. Private wells (deep groundwater) were used in the past (prior to 1978) in residential areas upgradient of the site. |

| Pesticide Handling Area | Located in the north central part of the site. A new Pesticide Storage building that is used to store and mix pesticides and herbicides replaced an old building in 1984. Reportedly, all liquid from the sumps is recycled, and no discharge, spills, or releases have been reported. The area is fenced. |

Groundwater: No pesticides were detected above CVs. Surface Soil: Aldrin (0.0483 ppm), chlordane (4.92 ppm), and dieldrin (1.1 ppm) were detected above CVs. |

RFI is complete. Remediation of pesticide residues reportedly conducted on old facility and surrounding area before construction of new facility. Resampling of soils is planned (date). |

No past, current, or anticipated future use of groundwater in site area. Access to the area is restricted. No children or other trespassers likely to access area. |

Sources: ABC Consulting 1996, 1998

3.5 Confidentiality and Privacy Issues

Some of the data collected during the public health assessment process may be considered confidential or private and may contain sensitive personal information. These include:

- Biologic/medical data (e.g., medical records, individual health outcome information, ATSDR Records of Activity [AROAs], and written logs that document an individual's medical condition). Typically, medical confidentiality issues arise as part of health studies or health surveillance activities that might evolve from the public health assessment process. Health assessors should be cautious before accepting or reviewing medical information containing personal identifiers (e.g., names, addresses, social security numbers). Medical facilities and state health departments generally have strict requirements pertaining to the handling of such confidential medical information. Before handling any data in which confidentiality may be an issue, you should consult with your supervisor, the assigned medical officer, or legal counsel. Health assessors are not typically required to handle this type of information as part of the public health assessment process and would more likely be reviewing environmental and exposure data and aggregate health outcome data (e.g., from cancer registries).

- Names of homeowners identified on maps (e.g., location of residences or private wells linked with environmental sampling data).

- Graphical displays of health outcome data (e.g., GIS maps) that may identify locations where a person with a particular illness or disease resides.

- Summaries of health information (e.g., informal door-to-door surveys conducted by community members) that might identify people with a particular health condition, especially if information is collected from a relatively small geographic area.

Information that needs to be presented in order to answer public health questions should be presented in such a fashion so that it protects the confidentiality or identity of the people involved. It is important that any such sensitive information not be disclosed in written products or in other communications (e.g., meetings, telephone calls). Further guidance is provided in ATSDR's "Confidentiality and Privacy Issues Related to Public Health Assessments and Health Consultations" (2001).

ATSDR. 1994. Environmental data needed for public health assessments: a guidance manual. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services. March 1994.

ATSDR. 2001. Confidentiality and privacy issues related to public health assessments and health consultations. Draft guidance document. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services. May 24, 2001.

The resources listed below are all on-line. No list of on-line resources is comprehensive or static: new resources are constantly being changed or added. All links were current at the time of publication.

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/, ATSDR's Web site, includes documentation on a wide range of agency activities and technical information that may be used to support public health assessment activities, including ATSDR's toxicological profiles, exposure registry information, ATSDR activities at hazardous waste sites (including PHAs released by ATSDR and its partners), and various technical reports. It also includes links to other credible science resources.

http://www.epa.gov/superfund/sites/npl/index.htm provides a listing of EPA National Priorities List (NPL) Superfund sites and an overview of their site status.

The Geographic Analysis Tool for Health and Environmental Research (GATHER) is ATSDR's interactive map server. It provides maps of site boundaries for selected hazardous waste sites, including geographic features and selected population data, as well as access to additional maps and spatial analyses created by GIS.

http://www.mapquest.com produce area maps that include locations of hospitals, schools, and other features of interest.

http://www.terrafly.com/ provides aerial photographs similarly to TerraServer, but also allows the user to enter street addresses (instead of just geographical coordinates).

http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/topo/state.html provides topographic maps of each state made available by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ provide access to satellite images, aerial photographs, maps, and digital data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

http://www.topozone.com provides access to USGS maps at 1:25,000, 1:100,000, or 1:200,000 scale.

http://www.census.gov/ and http://quickfacts.census.gov provide selected demographic and economic information collected by the U.S. Census Bureau.

http://tiger.census.gov/cgi-bin/mapbrowse-tbl can generate maps that include features such as streets, water bodies, and Indian reservations based on information from the U.S. Census Bureau.

http://www.geolytics.com. CensusCD can be purchased at this Web site.

http://mcdc2.missouri.edu/websas/xtabs3v2.html will generate 1990 demographic profiles for states, counties, ZIP codes, or census tracts.

http://www.epa.gov/tri/ contains EPA's Toxics Release Inventory (TRI).

http://www.scorecard.org was developed by Environmental Defense using data from TRI to provide information about sources of environmental releases by county.

http://www3.epa.gov/enviro/ is the access point for data from EPA's "Envirofacts Warehouse," which includes information about EPA-regulated facilities and their hazardous waste, air, water discharge, and other permits. The Web site also has a "Maps on Demand" service that will provide maps showing EPA-regulated facilities, schools, water bodies, hospitals, ZIP code boundaries, etc.

http://www.epa.gov/superfund/programs/risk/datause/partb.htm contains EPA's guidance for the usability of environmental pollution data.

http://www.epa.gov/quality/qs-docs/g4hw-final.pdf contains data quality objectives developed by EPA for hazardous waste site investigations.

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/ The National Center for Health Statistics site includes data on health status, lifestyle, and exposure to unhealthy influences, the onset and diagnosis of illness and disability, birth and death rates, and the use of health care nationally and by state in an A to Z format.

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/international/relres.html lists state health departments.

Local/State Contacts and Local News

http://www.50states.com/news/ provides a list of local newspapers by state.

http://www.nativeweb.org/ lists Native American organizations.

- Page last reviewed: November 30, 2005

- Page last updated: November 30, 2005

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir