Baylisascariasis

[Baylisascaris procyonis]

Causal Agents

Human baylisascariasis is caused by larvae of Baylisascaris procyonis, an intestinal nematode of raccoons.

Life Cycle

Baylisascaris procyonis completes its life cycle in raccoons, with humans acquiring the infection as accidental hosts (dogs serve as alternate definitive hosts, as they can harbor patent and shed eggs). Unembryonated eggs are shed in the environment  , where they take 2-4 weeks to embryonate and become infective

, where they take 2-4 weeks to embryonate and become infective  . Raccoons can be infected by ingesting embryonated eggs from the environment

. Raccoons can be infected by ingesting embryonated eggs from the environment  . Additionally, over 100 species of birds and mammals (especially rodents) can act as paratenic hosts

. Additionally, over 100 species of birds and mammals (especially rodents) can act as paratenic hosts  for this parasite: eggs ingested by these hosts hatch and larvae penetrate the gut wall and migrate into various tissues where they encyst

for this parasite: eggs ingested by these hosts hatch and larvae penetrate the gut wall and migrate into various tissues where they encyst  . The life cycle is completed when raccoons eat these hosts

. The life cycle is completed when raccoons eat these hosts  . The larvae develop into egg-laying adult worms in the small intestine

. The larvae develop into egg-laying adult worms in the small intestine  and eggs are eliminated in raccoon feces. Humans become accidentally infected when they ingest infective eggs from the environment; typically this occurs in young children playing in the dirt

and eggs are eliminated in raccoon feces. Humans become accidentally infected when they ingest infective eggs from the environment; typically this occurs in young children playing in the dirt  . Migration of the larvae through a wide variety of tissues (liver, heart, lungs, brain, eyes) results in VLM and OLM syndromes, similar to toxocariasis

. Migration of the larvae through a wide variety of tissues (liver, heart, lungs, brain, eyes) results in VLM and OLM syndromes, similar to toxocariasis  . In contrast to Toxocara larvae, Baylisascaris larvae continue to grow during their time in the human host. Tissue damage and the signs and symptoms of baylisascariasis are often severe because of the size of Baylisascaris larvae, their tendency to wander widely, and the fact that they do not readily die. Diagnosis is usually made by serology, or by identifying larvae in biopsy or autopsy specimens.

. In contrast to Toxocara larvae, Baylisascaris larvae continue to grow during their time in the human host. Tissue damage and the signs and symptoms of baylisascariasis are often severe because of the size of Baylisascaris larvae, their tendency to wander widely, and the fact that they do not readily die. Diagnosis is usually made by serology, or by identifying larvae in biopsy or autopsy specimens.

Geographic Distribution

Raccoons infected with Baylisascaris procyonis appear to be common in the Middle Atlantic, Midwest, and Northeast regions of the United States and are well documented in California and Georgia. Proven human cases have been reported in California, Oregon, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota, with a suspected case in Missouri.

Clinical Presentation

Human infections can be asymptomatic. However, because these larvae continue to grow and wander in the human host, infections often result in severe disease manifestations. Much like toxocariasis, infection with Baylisascaris can result in visceral larva migrans (VLM) or ocular larva migrans (OLM) syndromes. The larvae of B. procyonis have a tendency to invade the spinal cord, brain, and eye of humans, resulting in permanent neurologic damage, blindness, or death. Human infection with Baylisascaris appears to be rare. To date, 13 well documented Baylisascaris encephalitis cases, and 1 suspected case in a young girl with CNS larva migrans, have been reported. The prevalence of subclinical cases is unknown. Because there is no widely available definitive diagnostic test for humans infected with this parasite, many cases are not diagnosed initially.

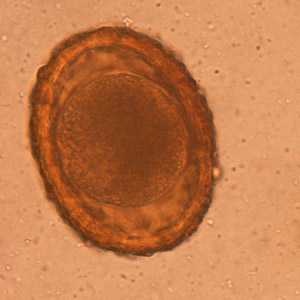

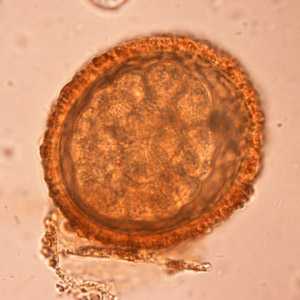

Baylisascaris procyonis eggs.

Figure A: Unembryonated egg of B. procyonis

Figure B: Egg of B. procyonis. In this specimen, the developing embryo has started to divide.

Figure C: Eggs of B. procyonis in a further state of cleavage.

Figure D: Eggs of B. procyonis in a further state of cleavage.

Figure E: Embryonated eggs of B. procyonis, showing the developing larva inside.

Figure F: Embryonated eggs of B. procyonis, showing the developing larva inside.

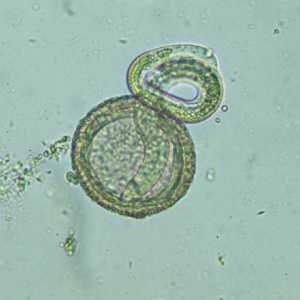

Baylisascaris procyonis hatching larvae.

Figure A: Larva of B. procyonis hatching from an egg.

Viable B. procyonis egg in formalin, recovered from a raccoon.

Figure A: Egg of B. procyonis in formalin-fixed stool from a raccoon. Animated image contributed by the Oregon State Public Health Laboratory.

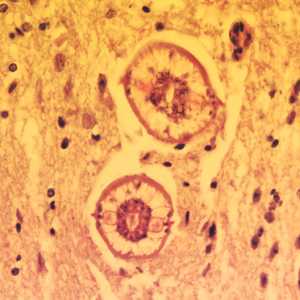

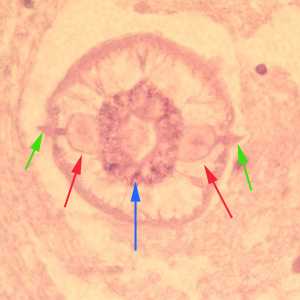

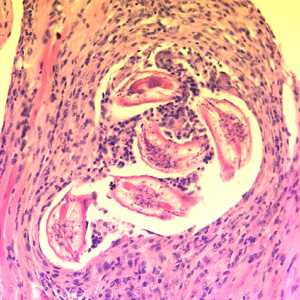

Larvae of Baylisascaris spp. in tissue.

Figure A: Cross-sections of larvae of B. columnaris in the brain of a laboratory-infected mouse. The larval morphology and microscopic manifestations would be similar with B. procyonis in human tissue.Image taken at 400x magnification.

Figure B: Higher magnification (1000x oil) of a cross-section of B. columnaris from the same specimen as Figure A. Notice the prominent alae (green arrows), excretory columns (red arrows) and multinucleate intestinal cells (blue arrow).

Figure C: Cross-sections of larvae of B. columnaris in muscle of a laboratory-infected mouse. The larval morphology and microscopic manifestations would be similar with B. procyonis in human tissue. Image taken at 400x magnification.

B. procyonis adults.

Figure A: Several adults of B. procyonis from a raccoon

Laboratory Diagnosis

Human infections are difficult to diagnose, and often the diagnosis is by exclusion of other causes. Results from complete blood count (CBC) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination would be consistent with parasitic infection, but tend to be nonspecific. Examination of tissue biopsies can be extremely helpful if a section of larva is contained, but removing an appropriate piece of tissue where the larva is actually present can be problematic. Ocular examinations revealing a migrating larva, larval tracks, or lesions consistent with a nematode larva are often the most significant clue to infection with Baylisascaris. Serologic testing can be extremely helpful in suspected cases; however, tests are not routinely in use nor widely available.

Treatment Information

In cases where suspicion of exposure is high, immediate treatment with albendazole (25-50 mg/kg per day by mouth for 10 – 20 days) may be appropriate. Treatment is successful when administered soon after exposure to abort the migration of larvae. Indications for immediate treatment may include known oral exposure to raccoon feces, presence of Baylisascaris eggs in the feces of the implicated animal or animals, and suspected oral exposure to raccoon feces in an area where the prevalence of raccoon infection is known to be high. Treatment should be initiated as soon as possible after ingestion of infectious material, ideally within three days. If albendazole is not immediately available, mebendazole or ivermectin may be used in the interim.

For clinical baylisascariasis, treatment with albendazole, at the dose given above, with concurrent corticosteroids to help reduce the inflammatory reaction is indicated to attempt to control the disease.

Albendazole

Oral albendazole is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Note on Treatment During Lactation

Mebendazole

Mebendazole is available in the United States only through compounding pharmacies.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Note on Treatment During Lactation

Note on Treatment in Pediatric Patients

Ivermectin

Oral ivermectin is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Note on Treatment During Lactation

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir