Free Living Amebic Infections

[Acanthamoeba spp.] [Balamuthia mandrillaris] [Naegleria fowleri] [Sappinia spp.]

Causal Agents

Naegleria fowleri and Acanthamoeba spp., are commonly found in lakes, swimming pools, tap water, and heating and air conditioning units. While only one species of Naegleria, N. fowleri, is known to infect humans, several species of Acanthamoeba, including A. culbertsoni, A. polyphaga, A. castellanii, A. astronyxis, A. hatchetti, A. rhysodes, A. divionensis, A. lugdunensis, and A. lenticulata are implicated in human disease. An additional agent of human disease, Balamuthia mandrillaris, is a related free-living ameba that is morphologically similar to Acanthamoeba in tissue sections in light microscopy. Sappinia is a genus of free-living amebae rarely isolated from humans; cysts and trophs have been found in the feces of many animals, including mammals and reptiles.

Life Cycles

Free-living amebae belonging to the genera Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, Naegleria and Sappinia are important causes of disease in humans and animals. Naegleria fowleri produces an acute, and usually lethal, central nervous system (CNS) disease called primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Acanthamoeba spp. and Balamuthia mandrillaris are opportunistic free-living amebae capable of causing granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) in individuals with compromised immune systems. Sappinia pedata has been implicated in a case of amebic encephalitis.

Acanthamoeba spp.

Balamuthia mandrillaris

Naegleria fowleri

Geographic Distribution

While infrequent, infections appear to occur worldwide.

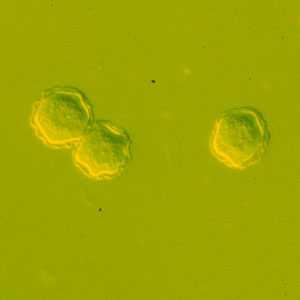

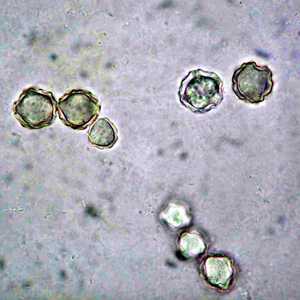

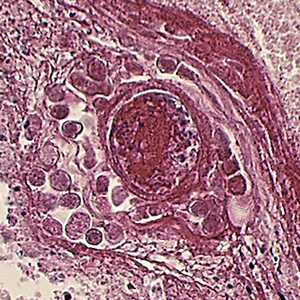

Acanthamoeba spp. cysts.

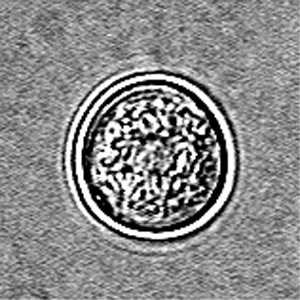

Figure A: Cysts of Acanthamoeba spp. in culture.

Figure B: Cysts of Acanthamoeba spp. in culture.

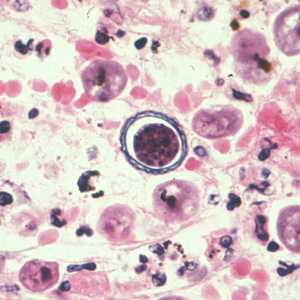

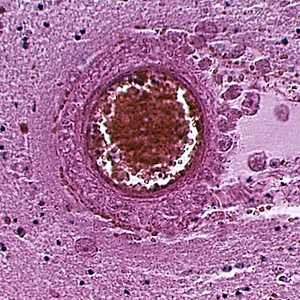

Figure C: Cyst of Acanthamoeba sp. from brain tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

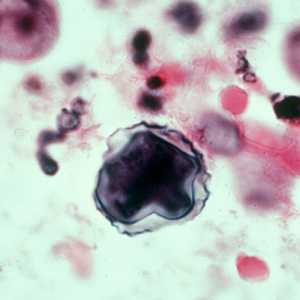

Figure D: Cyst of Acanthamoeba sp. from brain tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

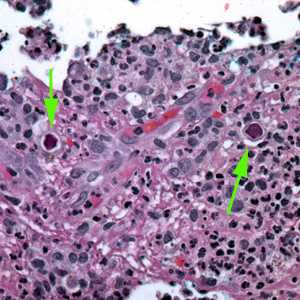

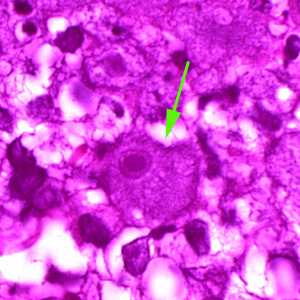

Figure E: Cysts of Acanthamoeba sp. (green arrows) in tissue, stained with H&E.

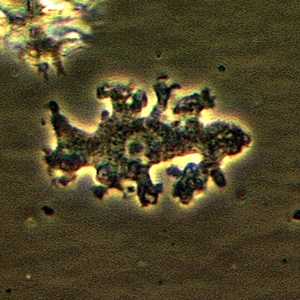

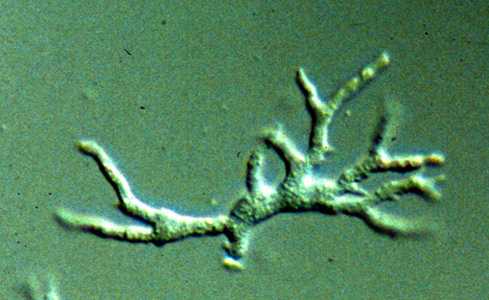

Acanthamoeba spp. trophozoites.

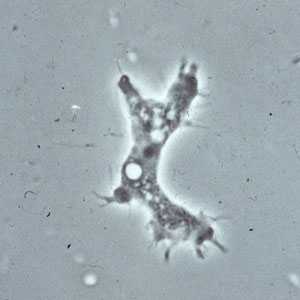

Figure A: Trophozoite of Acanthamoeba sp. from culture. Notice the slender, spine-like acanthapodia.

Figure B: Trophozoites of Acanthamoeba sp. from culture. Notice the slender, spine-like acanthapodia.

Figure C: Trophozoite of Acanthamoeba sp. in tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure D: Trophozoites of Acanthamoeba sp. in a corneal scraping, stained with H&E.

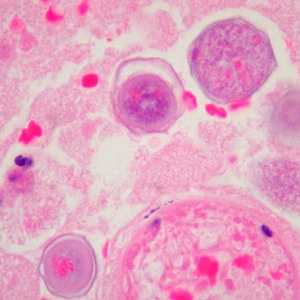

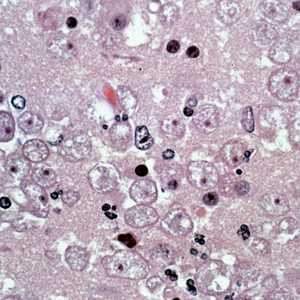

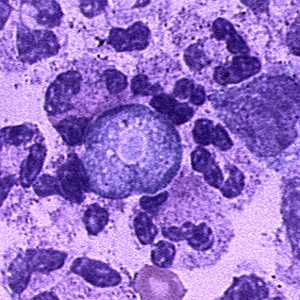

Balamuthia mandrillaris cysts.

Figure A: Cysts of B. mandrillaris.

Figure B: Close-up of one of the cysts in Figure A.

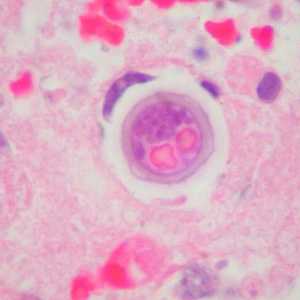

Figure C: Cyst of B. mandrillaris.

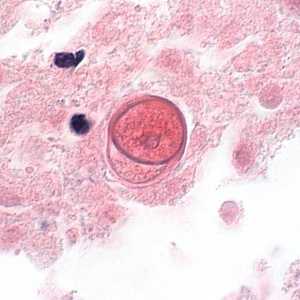

Figure D: Cyst of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure E: Cyst of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

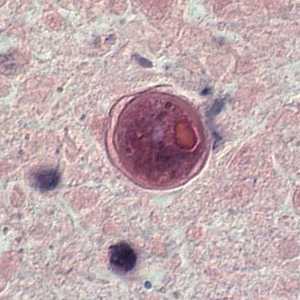

Figure F: Cyst of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E. Image courtesy of the University of Kentucky Hospital, Lexington, Kentucky.

Figure G: Cyst of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E. Image courtesy of the University of Kentucky Hospital, Lexington, Kentucky.

Figure H: Cysts of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E. Image courtesy of Cook Children’s Hospital, Fort Worth, Texas.

Figure I: Cyst of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E. Image courtesy of Cook Children’s Hospital, Fort Worth, Texas.

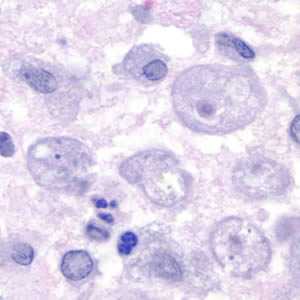

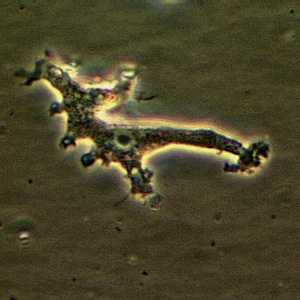

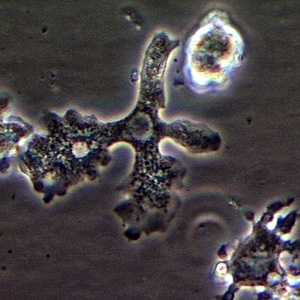

Balamuthia mandrillaris trophozoites.

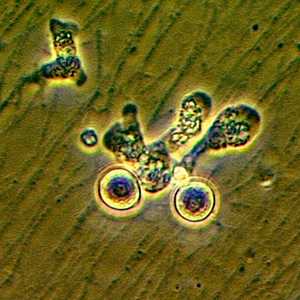

Figure A: Trophozoite of B. mandrillaris in culture.

Figure B: Trophozoite of B. mandrillaris in culture.

Figure C: Trophozoite of B. mandrillaris in culture.

Figure D: Trophozoite of B. mandrillaris in culture.

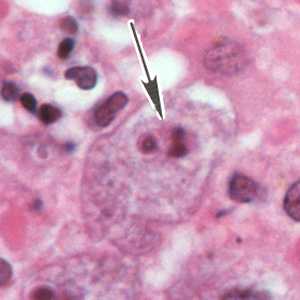

Figure E: Several trophozoites of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

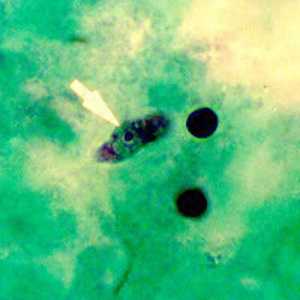

Figure G: A single trophozoite (black arrow) of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E.

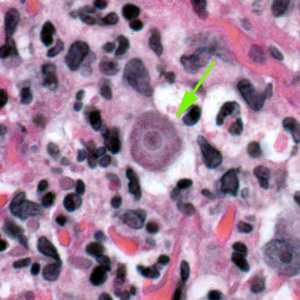

Figure F: A single trophozoite (green arrow) of B. mandrillaris in brain tissue, stained with H&E.

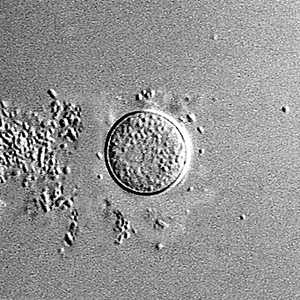

Naegleria fowleri cysts.

Figure A: Cyst of N. fowleri in culture.

Naegleria fowleri trophozoites.

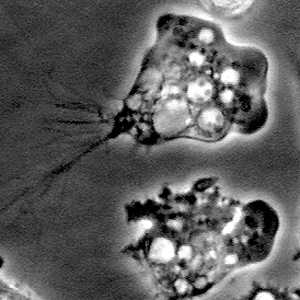

Figure A: Trophozoite of N. fowleri in culture.

Figure B: Trophozoites of N. fowleri in culture.

Figure C: Ameboflagellate trophozoite of N. fowleri.

Figure D: Trophozoite of N. fowleri in CSF, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure E: Trophozoite of N. fowleri in CSF, stained with trichrome. Image courtesy of the Texas State Health Department.

Sappinia spp. cysts and trophozoites.

Figure A: Cyst of Sappinia sp. in culture, viewed under differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

Figure B: Cysts of Sappinia sp. in culture, viewed under differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

Figure C: Trophozoite of Sappinia sp. in culture, viewed under DIC microscopy.

Figure D: Trophozoite of Sappinia sp. in culture, viewed under DIC microscopy.

Figure E: Trophozoite of Sappinia sp. viewed under DIC microscopy.

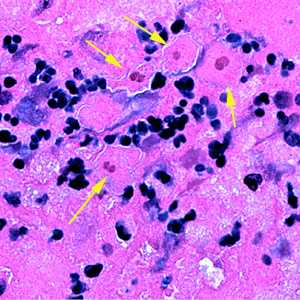

Figure F: Four trophozoites (yellow arrows) of S. pedata in brain tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). In three of the amebae, the two nuclei can easily be seen.

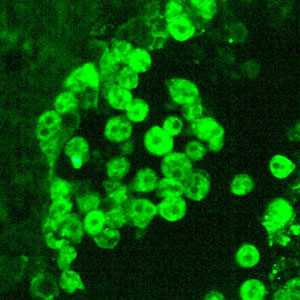

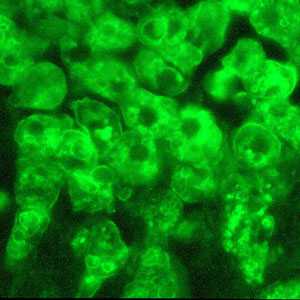

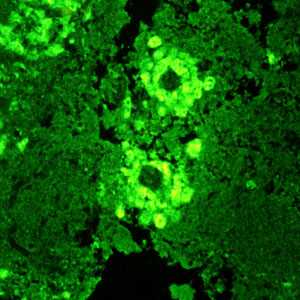

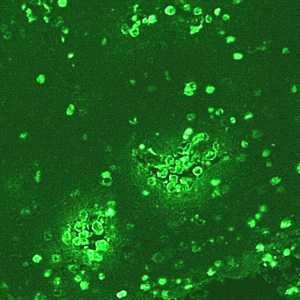

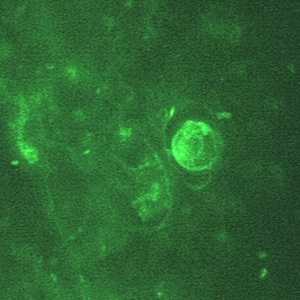

Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) assay for free-living amebic infections.

Figure A: IIF of Acanthamoeba sp. viewed under UV microscopy. This image was taken at 400x magnification.

Figure B: IIF of Acanthamoeba sp. viewed under UV microscopy. This image was taken at 1000x oil magnification.

Figure C: IIF of Balamuthia mandrillaris in brain tissue, viewed under UV microscopy.

Figure D: IIF of Naegleria fowleri in brain tissue, viewed under UV microscopy. This image was taken at 200x magnification.

Figure E: IIF of Naegleria fowleri in brain tissue, viewed under UV microscopy. This image was taken at 1000x oil magnification.

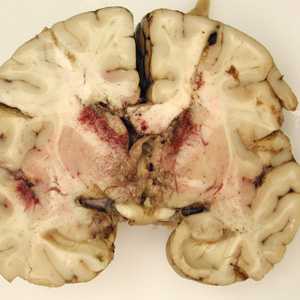

Gross pathology images in free-living amebic infections.

Figure A: Gross specimen of brain tissue from a patient who died of granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) caused by Balamuthia mandrillaris. The autopsy specimen revealed extensive necrotizing (mixed inflammatory, occasional giant cells, vasculitic) granulomatous encephalitis with a subependymal necroinflammatory process. Image courtesy of Cook Children’s Hospital, Fort Worth, Texas.

Figure B: Gross specimen of brain tissue from a patient who died of granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) caused by Balamuthia mandrillaris. The autopsy specimen revealed extensive necrotizing (mixed inflammatory, occasional giant cells, vasculitic) granulomatous encephalitis with a subependymal necroinflammatory process. Image courtesy of Cook Children’s Hospital, Fort Worth, Texas.

Diagnostic Findings

In Naegleria infections, the diagnosis can be made by microscopic examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). A wet mount may detect motile trophozoites, and a Giemsa-stained smear will show trophozoites with typical morphology. In Acanthamoeba infections, the diagnosis can be made from microscopic examination of stained smears of biopsy specimens (brain tissue, skin, cornea) or of corneal scrapings, which may detect trophozoites and cysts. Confocal microscopy or cultivation of the causal organism, and its identification by direct immunofluorescent antibody, may also prove useful. An increasing number of PCR-based techniques (conventional and real-time PCR) have been described for detection and identification of free-living amebic infections in the clinical samples listed above. Such techniques may be available in selected reference diagnostic laboratories.

Real-Time PCR

A real-time PCR was developed at CDC for identification of Acanthamoeba spp., Naegleria fowleri, and Balamuthia mandrillaris in clinical samples.1 This assay uses distinct primers and TaqMan probes for the simultaneous identification of these three parasites.

More on: TaqMan real-time PCR

References:

- Qvarnstrom Y, Visvesvara GS, Sriram R, da Silva AJ. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Naegleria fowleri. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44(10):3589-3595.

Treatment Information

Acanthamoeba

Early diagnosis is essential for effective treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Several prescription eye medications are available for treatment. However, the infection can be difficult to treat. The best treatment regimen for each patient should be determined by an eye doctor. If you suspect your eye may be infected with Acanthamoeba, see an eye doctor immediately.

Skin infections that are caused by Acanthamoeba but have not spread to the central nervous system can be successfully treated. Because this is a serious infection and the people affected typically have weakened immune systems, early diagnosis offers the best chance at cure.

Most cases of brain and spinal cord infection with Acanthamoeba (Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis) are fatal.

Balamuthia mandrillaris

Although there have been more than 200 cases of Balamuthia infection worldwide, few patients are known to have survived as a result of successful drug treatment[1,2]. Early diagnosis and treatment might increase the chances for survival[3].

Drugs used in treating Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis (GAE) caused by Balamuthia have included a combination of flucytosine, pentamidine, fluconazole, sulfadiazine and either azithromycin or clarithromycin[1,2,4,5]. Recently, miltefosine in combination with some of these other drugs has shown some promise[2]. Much more information is needed in treating patients with GAE due to Balamuthia.

References

- Perez MT, Bush LM. Balamuthia mandrillaris amebic encephalitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. Jul 2007;9(4):323-328.

- Martinez DY, Seas C, Bravo F, et al. Successful treatment of Balamuthia mandrillaris amoebic infection with extensive neurological and cutaneous involvement. Clin Infect Dis. Jul 15 2010;51(2):e7-11.

- Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Balamuthia amoebic encephalitis: an emerging disease with fatal consequences. Microb Pathog. Feb 2008;44(2):89-97.

- Cary LC, Maul E, Potter C, et al. Balamuthia mandrillaris meningoencephalitis: survival of a pediatric patient. Pediatrics. Mar 2010;125(3):e699-703.

- Drugs for Parasitic Infections: The Medical Letter; 2010.

Naegleria fowleri

Although most cases of primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) caused by Naegleria fowleri infection in the United States have been fatal (122/123 in the U.S., [1]), there have been two well-documented survivors in North America: one in California [2, 3] and one in Mexico [4]. It has been suggested that the survivor’s strain of Naegleria fowleri was less virulent, which contributed to the patient’s recovery. In laboratory experiments, the California survivor’s strain did not cause damage to cells as rapidly as other strains, suggesting that it is less virulent than strains recovered from other fatal infections [5].

Multiple patients have received treatment similar to the California survivor, including amphotericin B, miconazole/fluconazole/ketoconazole, and/or rifampin but only the patient in Mexico has survived making it difficult to determine the efficacy of the treatment regimen.

The survivors received the following medications:

| U.S. California Survivor [2, 3] (1978) | Mexico Survivor [4] (2003) |

|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | Amphotericin B |

| Rifampicin | Rifampicin |

| Miconazole – no longer available in US | Fluconazole |

| Dexamethasone | Dexamethasone |

| Sulfisoxazole (IV) – discontinued after Naegleria diagnosed | Ceftriaxone |

| Phenytoin |

Recently an investigational breast cancer and anti-leishmania drug, miltefosine [6], has shown some promise in combination with some of these other drugs. Miltefosine has shown ameba-killing activity against free-living amebae, including Naegleria fowleri, in the laboratory [7, 8]. Miltefosine has also been used to successfully treat patients infected with Balamuthia [9] and disseminated Acanthamoeba infection [10]. CDC now has a supply of miltefosine for treatment of Naegleria fowleri infection [11]. If you are a clinician and have a patient with suspected Naegleria or other free-living ameba infection, please contact the CDC Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100 to consult with a CDC expert regarding the use of this drug.

Sappinia

Treatment for the one identified case of Sappinia infection included the removal of a tumor in the brain and a series of drugs given to the patient after surgery. This treatment lead to the patient’s full recovery[1,2].

References

- Gelman, B.B., et al., Amoebic encephalitis due to Sappinia diploidea. JAMA, 2001. 285(19): p. 2450-1.

- Gelman, B.B., et al., Neuropathological and ultrastructural features of amebic encephalitis caused by Sappinia diploidea. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2003. 62(10): p. 990-8.

References

- Yoder JS, Eddy BA, Visvesvara GS, Capewell L, Beach MJ. The epidemiology of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in the USA, 1962-2008.

Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:968-75.

Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:968-75. - Seidel JS, Harmatz P, Visvesvara GS, Cohen A, Edwards J, Turner J. Successful treatment of primary amebic meningoencephalitis.

N Engl J Med. 1982;306:346-8.

N Engl J Med. 1982;306:346-8. - Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea.

FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:1-26.

FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:1-26. - Vargas-Zepeda J, Gomez-Alcala AV, Vasquez-Morales JA, Licea-Amaya L, De Jonckheere JF, Lores-Villa F. Successful treatment of Naegleria PAM using IV amphotericin B, fluconazole, and rifampin.

Arch Med Res. 2005;36:83-6.

Arch Med Res. 2005;36:83-6. - John DT, John RA. Cytopathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri in mammalian cell cultures.

Parasitol Res. 1989;76:20-5.

Parasitol Res. 1989;76:20-5. - Kaminsky R. Miltefosine Zentaris

. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:550-4.

. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:550-4. - Schuster FL, Guglielmo BJ, Visvesvara GS. In-vitro activity of miltefosine and voriconazole on clinical isolates of free-living amebas: Balamuthia mandrillaris, Acanthamoeba spp., and Naegleria fowleri.

J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2006;53:121-6.

J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2006;53:121-6. - Kim JH, Jung SY, Lee YJ, Song KJ, Kwon D, Kim K, Park S, Im KI, Shin HJ. Effect of therapeutic chemical agents in vitro and on experimental meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri.

[PDF - 7 pages]

[PDF - 7 pages] Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4010-16.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4010-16. - Martínez DY, Seas C, Bravo F, Legua P, Ramos C, Cabello AM, Gotuzzo E. Successful treatment of Balamuthia mandrillaris amoebic infection with extensive neurological and cutaneous involvement.

Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:e7-11.

Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:e7-11. - Aichelburg AC, Walochnik J, Assadian O, Prosch H, Steuer A, Perneczky G, Visvesvara GS, Aspöck H, Vetter N. Successful treatment of disseminated Acanthamoeba sp. infection with miltefosine.

[PDF - 4 pages]

[PDF - 4 pages] Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1743-6.

Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1743-6. - CDC. Investigational Drug Available Directly from CDC for the Treatment of Infections with Free-Living Amebae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(33):666.

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir

and trophozoites

and trophozoites  , in its life cycle. No flagellated stage exists as part of the life cycle. The trophozoites replicate by mitosis (nuclear membrane does not remain intact)

, in its life cycle. No flagellated stage exists as part of the life cycle. The trophozoites replicate by mitosis (nuclear membrane does not remain intact)  . The trophozoites are the infective forms, although both cysts and trophozoites gain entry into the body

. The trophozoites are the infective forms, although both cysts and trophozoites gain entry into the body  through various means. Entry can occur through the eye

through various means. Entry can occur through the eye  , the nasal passages to the lower respiratory tract

, the nasal passages to the lower respiratory tract  , or ulcerated or broken skin

, or ulcerated or broken skin  . When Acanthamoeba spp. enters the eye it can cause severe keratitis in otherwise healthy individuals, particularly contact lens users

. When Acanthamoeba spp. enters the eye it can cause severe keratitis in otherwise healthy individuals, particularly contact lens users  . When it enters the respiratory system or through the skin, it can invade the central nervous system by hematogenous dissemination causing granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE)

. When it enters the respiratory system or through the skin, it can invade the central nervous system by hematogenous dissemination causing granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE)  or disseminated disease

or disseminated disease  , or skin lesions

, or skin lesions  in individuals with compromised immune systems. Acanthamoeba spp. cysts and trophozoites are found in tissue.

in individuals with compromised immune systems. Acanthamoeba spp. cysts and trophozoites are found in tissue.

, or ulcerated or broken skin

, or ulcerated or broken skin  . When B. mandrillaris enters the respiratory system or through the skin, it can invade the central nervous system by hematogenous dissemination causing granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE)

. When B. mandrillaris enters the respiratory system or through the skin, it can invade the central nervous system by hematogenous dissemination causing granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE)  or disseminated disease

or disseminated disease  in individuals who are immune competent as well as those with compromised immune systems. B. mandrillaris cysts and trophozoites are found in tissue.

in individuals who are immune competent as well as those with compromised immune systems. B. mandrillaris cysts and trophozoites are found in tissue.

via the olfactory nerves causing primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Naegleria fowleri trophozoites are found in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and tissue, while flagellated forms are occasionally found in CSF. Cysts are not seen in brain tissue.

via the olfactory nerves causing primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Naegleria fowleri trophozoites are found in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and tissue, while flagellated forms are occasionally found in CSF. Cysts are not seen in brain tissue.