Loiasis

[Loa loa]

Causal Agent

Loa loa, a filarid nematode commonly referred to as the African eye worm.

Life Cycle

The vector for Loa loa filariasis are flies from two species of the genus Chrysops, C. silacea and C. dimidiata. During a blood meal, an infected fly (genus Chrysops, day-biting flies) introduces third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human host, where they penetrate into the bite wound  . The larvae develop into adults that commonly reside in subcutaneous tissue

. The larvae develop into adults that commonly reside in subcutaneous tissue  . The female worms measure 40 to 70 mm in length and 0.5 mm in diameter, while the males measure 30 to 34 mm in length and 0.35 to 0.43 mm in diameter. Adults produce microfilariae measuring 250 to 300 µm by 6 to 8 μm, which are sheathed and have diurnal periodicity. Microfilariae have been recovered from spinal fluids, urine, and sputum. During the day they are found in peripheral blood, but during the noncirculation phase, they are found in the lungs

. The female worms measure 40 to 70 mm in length and 0.5 mm in diameter, while the males measure 30 to 34 mm in length and 0.35 to 0.43 mm in diameter. Adults produce microfilariae measuring 250 to 300 µm by 6 to 8 μm, which are sheathed and have diurnal periodicity. Microfilariae have been recovered from spinal fluids, urine, and sputum. During the day they are found in peripheral blood, but during the noncirculation phase, they are found in the lungs  . The fly ingests microfilariae during a blood meal

. The fly ingests microfilariae during a blood meal  . After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and migrate from the fly's midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles of the arthropod

. After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and migrate from the fly's midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles of the arthropod  . There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae

. There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae  and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae

and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae  . The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the fly's proboscis

. The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the fly's proboscis  and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal

and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal  .

.

Geographic Distribution

Loa loa is found in Africa.

Clinical Presentation

Loiasis is often asymptomatic. Episodic angioedema (Calabar swellings) and subconjunctival migration of an adult worm can occur.

Microfilariae of Loa loa.

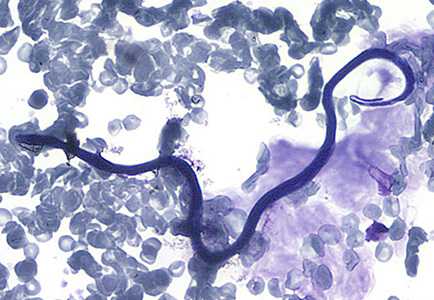

Figure A: Microfilaria of L. loa a thick blood smear from a patient from Cameroon, stained with Giemsa. Note the nuclei extending to the tip of the tail to the left of the image.

Figure B: Microfilaria of L. loa in a thick blood smear, stained with Giemsa.

Figure C: Microfilaria of L. loa in a thick blood smear, stained with Giemsa.

Figure D: Microfilaria of L. loa in a thin blood smear, stained with Giemsa.

Figure E: Microfilaria of L. loa in a thin blood smear, stained with Giemsa.

Figure F: Microfilaria of L. loa in a thin blood smear, stained with Giemsa.

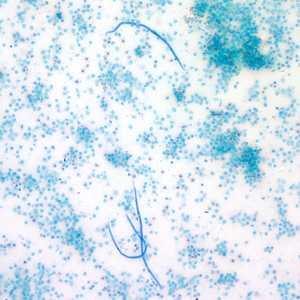

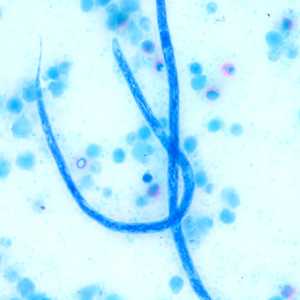

Figure G: Microfilariae of L. loa captured by the Knotts concentration technique. Image taken at 100x magnification.

Figure H: Higher magnification of the microfilariae in Figure G, taken at 500x oil magnification.

Adults of L. loa.

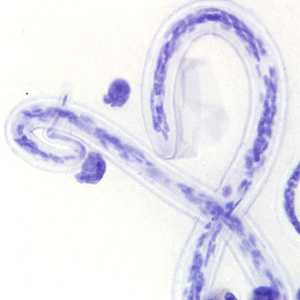

Figure A: Adult of L. loa removed from the eye of a patient. Image courtesy of the Georgia State Public Health Laboratory.

Figure B: Adult of L. loa removed from the eye of a patient. Image courtesy of the Georgia State Public Health Laboratory.

Diagnostic Findings

Loa loa is usually diagnosed by the finding of microfilaria in peripheral blood smears or adults in the subconjunctiva. The blood films may be thick or thin and stained with Giemsa or hematoxylin-and-eosin. For increased sensitivity, concentration techniques can be used. These include centrifugation of the blood sample lysed in 2% formalin (Knott's technique), or filtration through a Nucleopore® membrane. Microfilariae of L. loa exhibit diurnal periodicity and a diagnosis is best made from blood collected during the mid-day (10 AM-2 PM). The presence of Calabar swellings can aid in the diagnosis.

Treatment Information

The treatment of loiasis is complex and is best undertaken after consultation with experts who have experience in the treatment of the disease and prevention of complications of treatment. Additionally, there may be times when it is best not to treat the infection.

Surgical excision of migrating adult worms is an effective treatment for symptoms localized to the migrating worm and provides an opportunity for diagnosis. Systemic therapy would be required to cure the infection unless the patient is infected with only a single adult worm.

The drug of choice for the treatment of loiasis in patients without detectable microfilariae is diethylcarbamazine (DEC). Most patients will achieve cure, defined as resolution of symptoms, resolution of eosinophilia, and decreasing antifilarial antibody titers, with one or two courses of DEC. Some will require additional courses of DEC or a trial of albendazole. DEC is the treatment of choice because there is solid evidence that it kills both the microfilariae and the adult worms, resulting in quicker resolution of the infection. DEC can also be used to prevent infection in long-term travelers to endemic areas. The prophylactic dose is 300mg orally once a week.

There is some evidence that albendazole given 200mg twice daily for 21 days may be an effective treatment for loiasis that is refractory to DEC treatment. It may also be used to reduce microfilarial load prior to initiation of DEC treatment. As albendazole's mechanism of action is believed to be an embryotoxic effect and possibly a directly toxic effect on the adult worms, both of which reduce microfilaraemia levels more slowly than DEC, it does not appear to be prone to causing encephalopathy, though published data are limited.

Treatment of loiasis with antiparasitic agents may result in a brief increase of symptoms, such as Calabar swelling or pruritus. Some authors suggest that these symptoms might be attenuated with the concomitant use of antihistamines or corticosteroids during the first seven days of treatment. There is also the risk of fatal encephalopathy with DEC treatment; this risk has not been shown to be eliminated by corticosteroid treatment. More details on this are given below the treatment table.

Loa loa, unlike many other filarial parasites, do not contain Wolbachia so doxycycline is not an effective treatment.

| Treatment | Indication | Adult Dose | Pediatric Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) | Symptomatic loiasis with MF/mL <8,000 | 8–10 mg/kg orally in 3 divided doses daily for 21 days | 8–10 mg/kg orally in 3 divided doses daily for 21 days |

| Albendazole | Symptomatic loiasis, with MF/mL <8,000 and failed 2 rounds DEC OR Symptomatic loiasis, with MF/ml ≥8,000 to reduce level to <8,000 prior to treatment with DEC |

200 mg orally twice daily for 21 days | 200 mg orally twice daily for 21 days |

| Apheresis* followed by DEC | Symptomatic loiasis, with MF/mL ≥8,000 | N/A | N/A |

MF = microfilariae of L. loa

* Apharesis should be performed at an institution with experience in using this therapeutic modality for loiasis.

Albendazole

Oral albendazole is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Note on risk of fatal encephalopathy when treating loiasis:

Available data demonstrate that the risk of fatal encephalopathy in patients treated with DEC with microfilarial loads <8,000 microfilariae per mL approaches zero. In those patients with microfilarial loads ≥8,000 microfilariae per mL, apheresis can be used in specialized centers to reduce the load below the 8,000 threshold prior to beginning treatment. Some authors suggest a more conservative threshold of 2,500 microfilariae per mL for the initiation of treatment of loaisis. This lower threshold would need to be balanced with the risk associated with apheresis. There are some data available that suggest treating the patient with albendazole, 200mg twice daily for 21 day, may reduce the microfilarial load to acceptable levels, though re-measurement of levels after albendazole treatment would be required prior to treatment with DEC.

Note on treatment in patients with O. volvulus co-infection:

DEC is contraindicated in persons with onchocerciasis because of a risk of blindness and/or severe exacerbation of skin disease.

Note on obtaining the medication:

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) has been used worldwide for more than 50 years. Because this infection is rare in the U.S., the drug is no longer approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and cannot be sold in the U.S. Physicians can obtain the medication from CDC after confirmed positive lab results.

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir