Oesophagostomiasis

[Oesophagostomum spp.]

Causal Agents

Bursate nematodes in the genus, Oesophagostomum. Oesophagostomum bifurcum is the most-common species infecting humans in Africa.

Life Cycle

Common livestock such as sheep, goats, and swine, as well as non-human primates, are the usual definitive hosts for Oesophagostomum spp., but other animals, including humans and cattle, may also serve as definitive hosts. Eggs are shed in the feces of the definitive host , and may be indistinguishable from the eggs of Necator and Ancylostoma. Eggs hatch into rhabditiform (L1) larvae in the environment

, and may be indistinguishable from the eggs of Necator and Ancylostoma. Eggs hatch into rhabditiform (L1) larvae in the environment , given appropriate temperature and level of humidity. In the environment, the larvae will undergo two molts and become infective filariform (L3) larvae

, given appropriate temperature and level of humidity. In the environment, the larvae will undergo two molts and become infective filariform (L3) larvae . Worms can go from eggs to L3 larvae in a matter of a few days, given appropriate environmental conditions. Definitive hosts become infected after ingesting infective L3 larvae

. Worms can go from eggs to L3 larvae in a matter of a few days, given appropriate environmental conditions. Definitive hosts become infected after ingesting infective L3 larvae . After ingestion, L3 larvae burrow into the submucosa of the large or small intestine and induce cysts. Within these cysts, the larvae molt and become L4 larvae. These L4 larvae migrate back to the lumen of the large intestine, where they molt into adults

. After ingestion, L3 larvae burrow into the submucosa of the large or small intestine and induce cysts. Within these cysts, the larvae molt and become L4 larvae. These L4 larvae migrate back to the lumen of the large intestine, where they molt into adults , . Eggs appear in the feces of the definitive host about a month after ingestion of infective L3 larvae.

, . Eggs appear in the feces of the definitive host about a month after ingestion of infective L3 larvae.

Geographic Distribution

Oesophagostomum spp. are widely distributed wherever livestock is raised, but more common in the tropics and subtropics. The highest incidence in humans is in the northern regions of Togo and Ghana, where O. bifurcum (primarily a monkey parasite) appears to cycle naturally in the human populations. Sporadic cases in humans have also been recorded in Brazil, Malaysia, Indonesia, French Guiana, and West Africa

Clinical Presentation

Acute abdomen is the most-common manifestation in humans, mimicking an appendicitis. A low-grade fever and tenderness in the lower-right quadrant are the most-common symptoms; vomiting, anorexia, and diarrhea are less-common. Intestinal obstruction may also occur, mimicking a hernia. Patients may also present with large, painless cutaneous masses in the lower abdominal region. In rare instances, Oesophagostomum spp. will perforate the bowel wall, causing purulent peritonitis or migrate to the skin, producing cutaneous nodules.

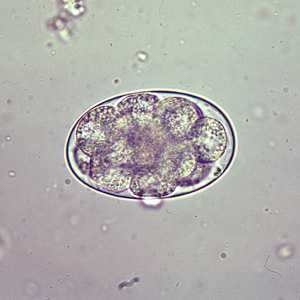

Eggs of Oesophagostomum spp.

Figure A: Egg of Oesophagostomum sp. in an unstained wet mount of stool.

Figure B: Egg of Oesophagostomum sp. in an unstained wet mount of stool.

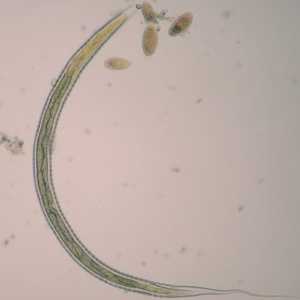

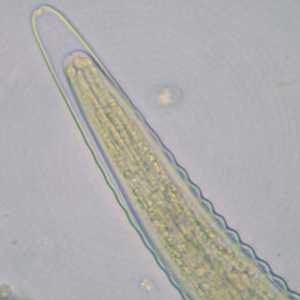

L3 infective larvae of Oesophagostomum spp.

Figure A: L3 larva of Oesophagostomum sp., obtained via coproculture from the feces of a baboon (Papio ursinus) in South Africa. Note the long, thin, pointed tail. Image courtesy of the UTC Baboon Research Unit, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Figure B: Higher-magnification of the anterior end of the specimen in Figure A. Note the long cephalic space.

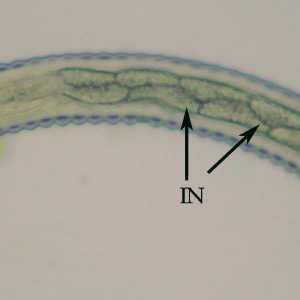

Figure C: Mid-section of the specimen in Figures A and B. Notice the alternating triangular-shaped intestinal cells (IN).

Figure D: Tail-end of the specimen in Figures A-C. Notice the long tail space (arrow) and long, tapering tail sheath.

Adults of Oesophagostomum spp.

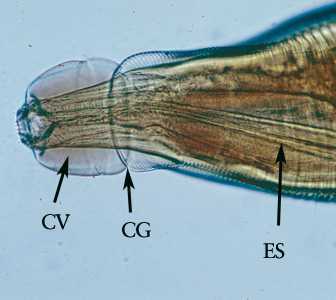

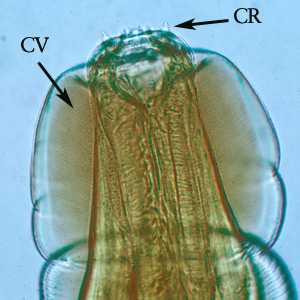

Figure A: Adult of Oesophagostomum sp.

Figure B: Higher magnification of the anterior end of the specimen in Figure A. Note the presence of the cephalic vesicle (CV), cephalic groove (CG) and esophagus (ES).

Figure C: Higher magnification of the anterior end of the specimen in Figures A and B. Note the presence of the cephalic vesicle (CV) and corona radiata (CR).

Figure D: Posterior end of a female Oesophagostomum sp., showing the pointed tail.

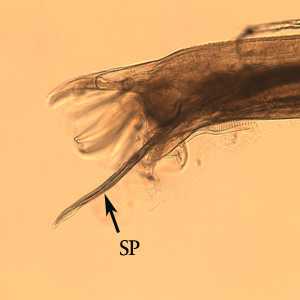

Figure E: Posterior end of male Oesophagostomum sp. Note the spicule (SP).

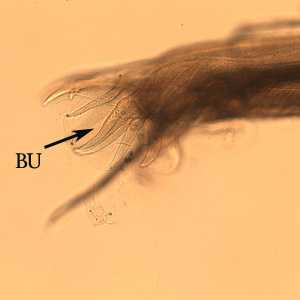

Figure F: Same specimen as in Figure E, but shown in a slightly different focal plane. Note the bursa (BU).

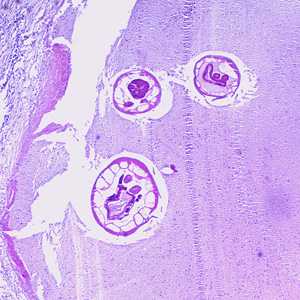

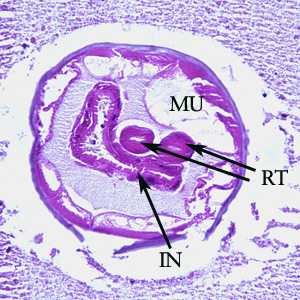

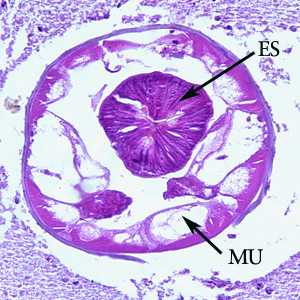

Oesophagostomum spp. in tissue specimens.

Figure A: Cross-section of an adult of Oesophagostomum sp. in a colon biopsy specimen from a patient from Africa, stained with H&E. Image taken at 40x magnification.

Figure B: Higher magnification (200x) of the specimen in Figure A. Note the large, platymyarian muscle cells (MU), intestine with brush border (IN), and paired reproductive tubes (RT).

Figure C: Higher-magnification (200x) of the specimen in Figure A. Note the large, platymyarian muscle cells (MU) and thick, muscled esophagus (ES).

Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosis is difficult during routine ova and parasite (O&P) examinations of stool, due to the similarity of Oesophagostomum eggs to the eggs of Necator and Ancylostoma. Eggs tend to be shed in greater numbers during cases of oesophagostomiasis than hookworm infection, however. Finding an intact worm during surgery or in a biopsy specimen can provide a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment Information

Treatment is usually limited to the surgical removal of adult worms from tissue. Albendazole (400 mg orally once or twice) or pyrantel pamoate (10 mg/kg orally for 2 days) has been shown to be effective for the removal of worms from the lumen of the large intestine.

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir