Insufficient Sleep Is a Public Health Problem

Continued public health surveillance of sleep quality, duration, behaviors, and disorders is needed to monitor sleep difficulties and their health impact.

Continued public health surveillance of sleep quality, duration, behaviors, and disorders is needed to monitor sleep difficulties and their health impact.

Sleep is increasingly recognized as important to public health, with sleep insufficiency linked to motor vehicle crashes, industrial disasters, and medical and other occupational errors.1 Unintentionally falling asleep, nodding off while driving, and having difficulty performing daily tasks because of sleepiness all may contribute to these hazardous outcomes. Persons experiencing sleep insufficiency are also more likely to suffer from chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, depression, and obesity, as well as from cancer, increased mortality, and reduced quality of life and productivity.1 Sleep insufficiency may be caused by broad scale societal factors such as round-the-clock access to technology and work schedules, but sleep disorders such as insomnia or obstructive sleep apnea also play an important role.1 An estimated 50-70 million US adults have sleep or wakefulness disorder1. Notably, snoring is a major indicator of obstructive sleep apnea.

In recognition of the importance of sleep to the nation’s health, CDC surveillance of sleep-related behaviors has increased in recent years. Additionally, the Institute of Medicine encouraged collaboration between CDC and the National Center on Sleep Disorders Research to support development and expansion of adequate surveillance of the U.S. population’s sleep patterns and associated outcomes. Two new reports on the prevalence of unhealthy sleep behaviors and self-reported sleep-related difficulties among U.S. adults provide further evidence that insufficient sleep is an important public health concern.

In recognition of the importance of sleep to the nation’s health, CDC surveillance of sleep-related behaviors has increased in recent years. Additionally, the Institute of Medicine encouraged collaboration between CDC and the National Center on Sleep Disorders Research to support development and expansion of adequate surveillance of the U.S. population’s sleep patterns and associated outcomes. Two new reports on the prevalence of unhealthy sleep behaviors and self-reported sleep-related difficulties among U.S. adults provide further evidence that insufficient sleep is an important public health concern.

Sleep-Related Unhealthy Behaviors

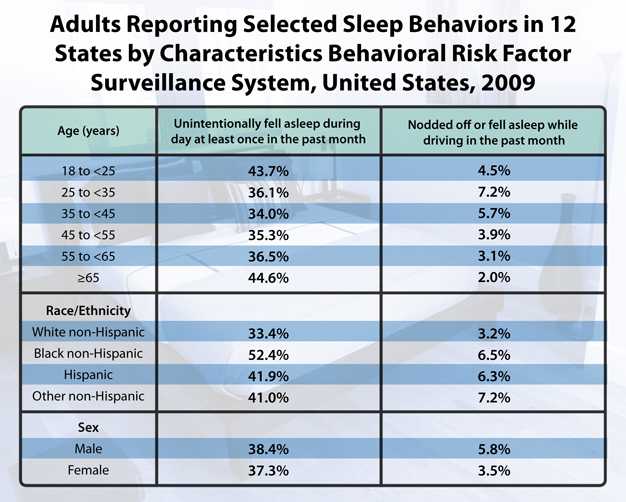

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey included a core question regarding perceived insufficient rest or sleep in 2008 (included since 1995 on the Health Related Quality of Life module) and an optional module of four questions on sleep behavior in 2009. Data from the 2009 BRFSS Sleep module were used to assess the prevalence of unhealthy/sleep behaviors by selected sociodemographic factors and geographic variations in 12 states. The analysis [1.1 MB], determined that, among 74,571 adult respondents in 12 states, 35.3% reported <7 hours of sleep during a typical 24-hour period, 48.0% reported snoring, 37.9% reported unintentionally falling asleep during the day at least once in the preceding month, and 4.7% reported nodding off or falling asleep while driving at least once in the preceding month. This is the first CDC surveillance report to include estimates of drowsy driving and unintentionally falling asleep during the day. The National Department of Transportation estimates drowsy driving to be responsible for 1,550 fatalities and 40,000 nonfatal injuries annually in the United States.2

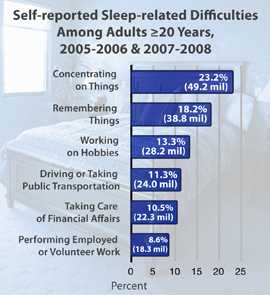

Self-reported Sleep-related Difficulties Among Adults

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) introduced the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire in 2005 for participants 16 years of age and older. This analysis [PDF – 1.1MB] was conducted using data from the last two survey cycles (2005–2006 and 2007–2008) to include 10,896 respondents aged ≥20 years. A short sleep duration was found to be more common among adults ages 20–39 years (37.0%) or 40–59 years (40.3%) than among adults aged ≥60 years (32.0%), and among non-Hispanic blacks (53.0%) compared to non-Hispanic whites (34.5%), Mexican-Americans (35.2%), or those of other race/ethnicity (41.7%). Adults who reported sleeping less than the recommended 7–9 hours per night were more likely to have difficulty performing many daily tasks.

How Much Sleep Do We Need? And How Much Sleep Are We Getting?

How much sleep we need varies between individuals but generally changes as we age. The National Institutes of Health suggests that school-age children need at least 10 hours of sleep daily, teens need 9-105 hours, and adults need 7-8 hours. According to data from the National Health Interview Survey, nearly 30% of adults reported an average of ≤6 hours of sleep per day in 2005-2007.3 In 2009, only 31% of high school students reported getting at least 8 hours of sleep on an average school night.4

Sleep Hygiene Tips

The promotion of good sleep habits and regular sleep is known as sleep hygiene. The following sleep hygiene tips can be used to improve sleep.

- Go to bed at the same time each night and rise at the same time each morning.

- Avoid large meals before bedtime.

- Avoid caffeine and alcohol close to bedtime.

- Avoid nicotine.

(Sleep Hygiene Tips adapted from the National Sleep Foundation)

References

- Institute of Medicine. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

- US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, National Center on Sleep Disorders Research, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Drowsy driving and automobile crashes [National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Web Site]. Available at http://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/drowsy_driving1/Drowsy.html#NCSDR/NHTSA Accessed February 10, 2011.

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2005–2007. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 10(245). 2010.

- CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR 2010;59:SS-5.

More Information

- Page last reviewed: September 3, 2015

- Page last updated: September 3, 2015

- Content source:

- National Center for Chronic Disease and Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Adult and Community Health

- Page maintained by: Office of the Associate Director for Communication, Digital Media Branch, Division of Public Affairs

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir