EHDI Guidance Manual Chapters

Chapter 5: Privacy, Confidentiality and Security of the EHDI-IS

Chapter Objectives

This chapter will help you to:

- Describe federal regulations and legislation related to the collection and exchange of screening, diagnostic evaluation, and early intervention (EI) data

- Understand what protected health information (PHI) is and how the information is exchanged

- Understand the methods for de-identification of PHI according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Recognize the different types of data security standards that may affect EHDI-IS

- Understand how different regulations and legislation affect information sharing

- Understand the importance of having relevant and clear policies in place for sharing and protecting EHDI-IS information

- Understand how to safeguard privacy and security of EHDI-IS information

Federal Regulations and Legislation Related to the Collection and Exchange of EHDI Information System (EHDI-IS) Data

Jurisdictional EHDI programs have been established to ensure the receipt of effective newborn hearing screening, diagnostic, follow-up, and early intervention services for deaf and hard of hearing children. Each year, jurisdictions are asked to voluntarily submit aggregate EHDI data for the CDC Hearing Screening and Follow-up Survey (HSFS) to demonstrate the jurisdiction’s ability to document and track EHDI services. The HSFS is a voluntary survey that gathers non-estimated data related to the receipt of hearing screening, diagnostic testing, and early intervention enrollment for all occurrent births within a jurisdiction in a given year. As discussed in Chapter 4, your jurisdictional EHDI-IS can help ensure that all children receive recommended and time-sensitive EHDI services. Your EHDI-IS, computer based or otherwise, is a tracking and surveillance system. It allows your jurisdictional EHDI program to document and track infants that have or have not received recommended services at any step of the EHDI 1-3-6 process. For example, an infant who has no record of undergoing hearing screening before hospital discharge might miss being screened if the hospital did not report to the state or territory that the infant was not screened prior to discharge. When the jurisdictional EHDI program is not informed of the missed newborn hearing screening, efforts may not be made to have the infant screened.

To support tracking and surveillance efforts, an effective EHDI-IS collects accurate and complete data and exchanges information between hospitals, audiologists, physicians, and Part C Early Intervention programs. Additionally, appropriate measures are taken to ensure that the sharing of the data meets the needs of EHDI programs as well as protects individual privacy. In the context of an EHDI system where patients are infants and young children, privacy may be defined as the right of the patient’s parents/legal guardian to hold their child’s information in secret and free from the knowledge of others. The information that is shared as a result of the clinical relationship must be protected and held confidential. Several federal regulations and legislation have guided the collection and exchange of EHDI-IS data and impacted health information technology. Links to each of the federal regulations and legislation covered in this chapter are provided below:

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

- The Family Education Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA)

- Part C regulations of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

- The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act)

The following subsections provide an overview of each of the federal regulations and legislation mentioned above. Later in this chapter, we cover how these regulations and legislation relate to EHDI programs. In addition to federal regulations and legislation, consider reviewing the EHDI laws and statutes in your state. State newborn hearing screening statutes can be accessed at the National Conference of State Legislatures website and a detailed state-by-state early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) laws and regulations PowerPoint.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

The HIPAA Act is often recognized as both a patient information privacy law and an electronic patient information security law. However, it encompasses a number of regulations. The HIPAA Act (Public Law 104-191) is made up of five titles. Title II of HIPAA defines the policies, procedures and guidelines for maintaining the privacy and security of individually identifiable health information. Per the requirements of Title II, the HHS has promulgated five rules regarding Administrative Simplification: the Privacy Rule, the Transactions and Code Sets Rule, the Security Rule, the Unique Identifiers Rule, and the Enforcement Rule. A description of each rule is listed below. Of the five rules listed, the most pertinent rules to your EHDI-IS are the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule.

The Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information (Privacy Rule) establishes national standards to preserve the overall confidentiality of protected health information (PHI) regardless of type (e.g. verbal, paper, and electronic). The Privacy Rule regulates how covered entities use and disclose PHI. At HHS, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has oversight and enforcement responsibilities for the Privacy Rule.

A summary of the Privacy Rule is available United States Department of Health & Human Services website. The Privacy Rule does the following:

- Protects individuals’ health records and other individually identifiable health information created, maintained, or received by or on behalf of covered entities and their business associates

- Protects individuals’ PHI by regulating the circumstances under which covered entities may use and disclose protected health information

- Requires covered entities to have contracts or other arrangements in place with business associates that perform functions for or provide services to, or on behalf of, the covered entity

- Gives individuals rights with respect to their protected health information, including rights to examine and obtain a copy of their health records and to request corrections

Public Health Authorities Performing Covered Functions

Public health authorities at the federal, tribal, state, or local levels that perform covered functions (e.g., providing health care or insuring individuals for health care costs) may be subject to the Privacy Rule’s provisions as covered entities. Covered entities can be institutions, organizations, or persons. For example, hospitals, academic medical centers, physicians, and other health care providers who electronically transmit claims transaction information directly or through an intermediary to a health plan are covered entities.

HIPAA defines covered entities as (1) health plans, (2) health care clearinghouses, and (3) health care providers who electronically transmit any health information in connection with transactions for which HHS has adopted standards. The transactions generally include billing and payment for services or insurance coverage. CDC and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have provided guidance on the HIPAA Privacy Rule and public health authorities. The Centers of Medicare & Medicaid also have a tool to determine if an organization is a covered entity.

Functions that may make public health authorities covered entities include:2

- Public health authorities as covered health care providers. A health care provider is a provider of services (as defined in section 1861(u) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. 1395x(u)), a provider of medical or health services (as defined in section 1861(s) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. 1395x(s)), and any other person or organization who furnishes, bills, or is paid for health care in the normal course of business. A public health authority is a covered health care provider if it performs electronic transactions covered by the HIPAA Transactions Rule as part of its activities. The fact that these activities are conducted in pursuit of a public health goal (e.g., early hearing detection and intervention) does not preclude the public health authority from being a covered entity. In the case of EHDI, jurisdictional EHDI programs may serve as both a covered entity and public health authority. In some jurisdictions, an EHDI program may be directly responsible for the delivery of health care services. For example, an EHDI program may be housed at the state health department with services delivered through local health departments. Some of the health care services offered may include well child care, newborn screening, family planning, immunizations, cancer screening, HIV/STI testing and counseling, chronic disease management and screening, home health services, and women, infant, and children (WIC) services.

- Public health authorities as health plans. A health plan is an individual or group plan that provides or pays the cost of medical care (as defined in section 2791(a)(2) of the PHS Act, 42 U.S.C. 300gg-91(a)(2)). This specifically includes government health plans (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, or Veterans Health Administration). However, health plans under the Privacy Rule exclude government funded programs whose principal activity is the direct provision of health care to persons or the making of grants to fund the direct provision of health care to persons [45 CFR §160.103]. Examples include the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act.

- Public health authorities as health care clearinghouses. A health care clearinghouse is a public or private entity, including a billing service, repricing company, community health management information system or community health information system, and “value added” networks. It is possible but unlikely that a public health authority may be a health care clearinghouse. According to CDC guidance, a public health authority might be a health care clearinghouse if it receives “health information from another entity and translates that information from a non-standard format into a standard transaction or standard data elements (or vice versa)”.4 Specifically, a public health authority may be a health care clearinghouse if it electronically transmits any health information in connection with transactions for which HHS has adopted standards. Generally, these transactions concern billing and payment for services or insurance coverage. Refer to the Transactions and Code Sets Rule section of this chapter for more information (add section link).

- Public health agencies as hybrid entities. A hybrid entity is a public health agency that has both covered and non-covered functions. By designating itself as a hybrid entity, a public health authority can carve out its non-covered functions. Thus, “the majority of Privacy Rule provisions only apply to its health care component, which is required to comply with the Privacy Rule requirements, including using and disclosing PHI only as authorized, meeting the administrative requirements, accounting for disclosure of PHI, and providing a notice of practices.” However, such a designation does not preclude the public health authority from continuing to conduct authorized public health functions. Under 45 CFR 164.506, a covered entity is permitted to use or disclose protected health information to the individual or for the treatment, payment, or health care operations. As stated above, some jurisdictional EHDI Programs may serve as both a covered entity and a public health authority. When they serve both roles, they may use and disclose PHI for public health purposes to the same extent that it would be permitted to disclose PHI as a public health authority. Hence, EHDI programs can obtain personally identifiable screening information without signed consent from hospitals and health care providers who perform the hearing screening.

For information on sharing PHI electronically, go to the HealthIT.gov website. Under the HIPAA Privacy Rule (45 CFR 164.501), covered entities including EHDI programs can use and disclose PHI to another covered entity for the following health care operation activities without patient consent or authorization:

- Conducting quality assessment and improvement activities

- Developing clinical guidelines

- Conducting patient safety activities

- Conducting population-based activities relating to improving health or reducing health care cost

- Developing protocols

- Conducting case management and care coordination (including care planning)

- Contacting health care providers and patients with information about treatment alternatives

- Reviewing qualifications of health care professionals

- Evaluating performance of providers and/or health plans

- Conducting training programs or credentialing activities

- Supporting fraud and abuse detection and compliance programs

Before PHI can be shared among covered entities for one of the reasons noted above, the following three requirements under the HIPAA Privacy Rule must be met:

- Both covered entities must have or have had a relationship with the patient (can be a past or present patient).

- The PHI requested must pertain to the relationship.

- The discloser must disclose only the minimum information necessary for the health care operation at hand.

In the context of EHDI, patients are infants and young children. Privacy is defined as the right of the patient’s parents/legal guardian to hold their child’s clinical information in secret and free from the knowledge of others. The clinical relationship is defined as the child’s screening, diagnostic, and EI data shared within the EHDI program, and PHI may be shared for the purposes of treatment, payment, or health care operations.

The Security Standards for the Protection of Electronic Protected Health Information (Security Rule) establishes a national set of security standards for PHI that is held or transferred in electronic form. The Security Rule operationalizes the protections contained in the Privacy Rule by addressing the technical and non-technical safeguards that organizations called “covered entities” must put in place to secure individuals’ “electronic protected health information” (e-PHI). A summary of the Security Rule is available Health and Human Services website. The Security Rule requires:

- Covered entities to implement certain administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to protect electronic information. Specifically, covered entities must

- Ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of all e-PHI they create, receive, maintain or transmit;

- Identify and protect against reasonably anticipated threats to the security or integrity of the information;

- Protect against reasonably anticipated, impermissible uses or disclosures; and

- Ensure compliance by their workforce.

- Covered entities to have contracts in place with their business associates that all business associates will appropriately safeguard the electronic protected health information they receive, create, maintain, or transmit on behalf of the covered entities

Transactions and Code Sets Rule

Under HIPAA, certain transaction and code sets standards were adopted to create a uniform way to perform electronic data interchange (EDI) transactions for submitting, processing, and paying claims. Electronic transactions are used in health care to increase efficiencies in operations, improve the quality and accuracy of information, and reduce the overall costs to the system. These transactions include claims and encounter information, payment and remittance advice, claims status, eligibility, enrollment and disenrollment, referrals and authorizations, coordination of benefits, and premium payment. Code sets classify medical diagnosis, procedures, diagnostic tests, treatment, equipment and supplies. Code sets outlined in HIPAA include:

- ICD-10 – International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition

- Health Care Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS)

- CPT – Current Procedure Terminology

- CDT – Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature

- NDC – National Drug Codes

These code sets are used in medical claims for hearing screening and diagnostics. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website can be accessed for more information on transactions and code sets.

Unique Identifiers Rule

HIPAA requires that employers and health care providers have standard national numbers to identify them on standard transactions. The Employer Identification Number (EIN) is issued by the Internal Revenue Services and was adopted as the identifier for employers effective July 30, 2002. The National Provider Identifier (NPI) is a unique 10-digit number. Individuals or organizations apply for NPIs through the CMS National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES). Covered health care providers, health plans, and health clearinghouses use NPIs in the administrative transactions adopted under HIPAA. As covered entities, jurisdictional EHDI programs may use NPIs in their administrative transactions for hearing screening and diagnostic testing. In some cases, NPIs can be used for tracking and surveillance purposes to ensure recommended services. For example, an EHDI program may opt to use medical license numbers or NPIs to follow-up with audiologists and medical providers to track the services provided for deaf and hard of hearing children. This ensures that the EHDI program is receiving the necessary information to confirm that infants who missed screening or failed the initial hearing screening in the hospital are getting recommended services.

The Enforcement Rule provides standards for the enforcement of all the Administrative Simplification Rules.

The HHS Office for Civil Rights is responsible for enforcing the Privacy and Security Rules with voluntary compliance activities and civil money penalties. For more information on HIPAA, visit the Office for Civil Rights’ HIPAA website. The website offers more detailed information on the following categories: What’s New in Privacy, For Consumers, General Background Information, HIPAA Regulations & Standards, Educational Materials, HIPAA Related Links, and Compliance & Enforcement.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99) is a federal law that applies to all schools receiving funds from the U.S. Department of Education and protects the privacy of student education records. Health care information, including hearing screening and diagnostic information, is generally part of the education record especially if the child enrolls in Part C. FERPA gives parents certain rights with respect to their child’s education record. These rights include the right to inspect and request corrections to the record. FERPA generally prohibits the disclosure of any personally identifiable information contained in an education record without the appropriate written consent. Under FERPA, schools may release any information to parents without the consent of the eligible student if the student is a dependent for tax purposes under the IRS rules. The educational rights transfer to the student when he or she reaches the age of 18 or attends a school beyond the high school level.

There are limited exceptions to the FERPA consent requirement– the studies exemption and the audit or evaluation exemption. An educational agency or institution may disclose personally identifiable information (PII) from education records without consent to organizations conducting studies for, or on its behalf. A written agreement with the organization is required specifying the purposes of the study and the use and destruction of the information (34 CFR § 99.31(a)(6)). Studies must be only for the “purpose of developing, validating, or administering predictive tests; administering student aid programs; or improving instruction.” Schools may also disclose PII from students’ education records without consent to authorized representatives of State and local educational authorities, the Secretary of Education, the Comptroller General of the United States, and the Attorney General of the United States for the “audit or evaluation of Federal or State supported education programs, or in connection with the enforcement of Federal legal requirements that relate to those programs” (34 CFR §§ 99.31(a)(3) and 99.35). More guidance on FERPA can be found at the U.S. Department of Education’s website link.

Part C Federal Regulations for Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 (IDEA)

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (Public Law 108-446) mandates that all states must provide children, including those with disabilities (e.g., deaf and hard of hearing children), with a free, appropriate public education (FAPE). Part C of IDEA is a federal program that assists states in operating a statewide program of early intervention (EI) services for infants and toddlers with disabilities (birth – 2 years) and their families. IDEA mandates that EI services must be provided by qualified personnel, in natural environments and at no cost to the families (except where states provide for a system of payment, such as a sliding scale). The final Part C Federal Regulations for IDEA 2004 was published on September 28, 2011 and can be found here.

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act made modifications to the HIPAA Privacy, Security, and Enforcement Rules. The HITECH Act Final Rule can be accessed in Volume 78 Number 17 of the Federal Register. The HITECH Act established the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s (ONC) into law. It provides the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services with the authority to establish programs to improve health care quality, safety, and efficiency through the promotion of health information technology (IT), including the electronic health records and private and secure electronic health information exchange.

The HITECH Act of 2009 added new protections to the regulations from the original 1996 HIPAA authority. The new regulations are meant to improve patient privacy and security protections by:

- Extending the Office for Civil Rights’ enforcement to business associates and covered entities,

- Strengthening individuals’ rights to request and receive their medical information in electronic form, and

- Setting new limits on the use and sale of individuals’ information.

Section 13424(c) of the HITECH Act requires the Secretary of HHS to issue guidance on how to best implement the requirements for the de-identification of health information contained in the Privacy Rule. The full guidance regarding methods for de-identification of protected health information in accordance to the HIPAA Privacy Rule can be found in Guidance Regarding Methods for De-identification of Protected Health Information in Accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. In addition, an overview of the de-identification standard is covered later in this chapter. To get a better understanding of legal issues related to sharing clinical health data with public health agencies, go to the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials website.

Defining protected health information (PHI)

The HIPAA Privacy Rule protects most “individually identifiable health information” that is held or transmitted by a covered entity or its business associate in any form of medium (electronic, paper or oral). The Privacy Rule (45 CFR 160.103) calls this information, protected health information.

Health information is any information, including genetic information, whether oral or recorded in any form or medium, that:

- Is created or received by a health care provider, health plan, public health authority, employer, life insurer, school or university, or health care clearinghouse; and

- Relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual; the provision of health care to an individual; or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual.

Individually identifiable health information is a subset of health information, including demographic information collected from an individual, that:

- Is created or received by a health care provider, health plan, employer, or health care clearinghouse; and

- Relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual; the provision of health care to an individual; or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual; and

- That identifies the individual; or

- With respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe the information can be used to identify the individual.

Protected health information (PHI) is individually identifiable health information:

- Except those provided in paragraph (2) of this definition, that is:

- Transmitted by electronic media;

- Maintained in electronic media; or

- Transmitted or maintained in any other form or medium.

- Protected health information excludes individually identifiable health information in:

- Education records covered by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, as amended, 20 U.S.C. 1232g;

- Records described at 20 U.S.C. 1232g(a)(4)(B)(iv); and

- Employment records held by a covered entity in its role as employer.

Under the HIPAA Privacy Rule, examples of PHI include medical records, laboratory reports, and hospital bills. Each of these documents contain an identifier, such as a patient’s name, and identifying health data that can be used to identify an individual.

In contrast, a health plan report that provides the average age of its members (e.g., 55) would not be considered to be PHI. Although aggregated information from individual records were used, the reported information does not identify any individual plan members and provides no reason that this information could be used to identify an individual.

Identifying information alone, e.g., names, residential addresses, or phone numbers, would not necessarily be designated as PHI. This type of information can be reported as part of a publicly accessible data source, such as a phone book, and is not related to heath data. However, if this information was listed with a health condition, health care provision or payment data, then this information would be considered PHI.

Note the definitions described above are adapted from the HHS Information Privacy website, which have been paraphrased from the regulatory text. For the actual definitions, please refer to the Electronic Code of Federal Regulations website.

De-identification Methods for PHI

There are certain measures that can be taken to secure and protect individually identifiable health information. De-identification refers to the process by which identifiers are removed from EHDI-IS data. Two options have been recommended by CDC and HHS to de-identify PHI., Not only does de-identification mitigate risks to the individuals, it also supports the use of data for follow-up, early intervention enrollment, and other additional uses.

As mentioned in Chapter 4, according to CDC and HHS guidance, EHDI-IS data should be stripped of any identifying information (i.e., name, Social Security number, etc.), with the possible exception of an analysis being done ONLY on a jurisdiction’s secure server. All identifying information is stripped away for security even if it is on a “jurisdiction” laptop. Ideally, person-ID numbers used by the EHDI-IS or state data systems are changed to a new random number. This would make the data unidentifiable to anyone other than the person who created the file. Detailed recordkeeping of the random number assignments are maintained by the person who created the data file or data manager. If a discrepancy occurs in the data, the individual can go back to original record to verify and validate the information.

The Privacy Rule was designed to protect PHI. Under §164.502(d) of the Privacy Rule, a covered entity or its business associate can create information that is not individually identifiable by following the de-identification standard and implementation specifications in §164.514(a)-(c). Once the personal identifiers are removed, the data is no longer considered PHI or covered under the Privacy Rule. You can no longer use the data to identify an individual (Grad, 2005).

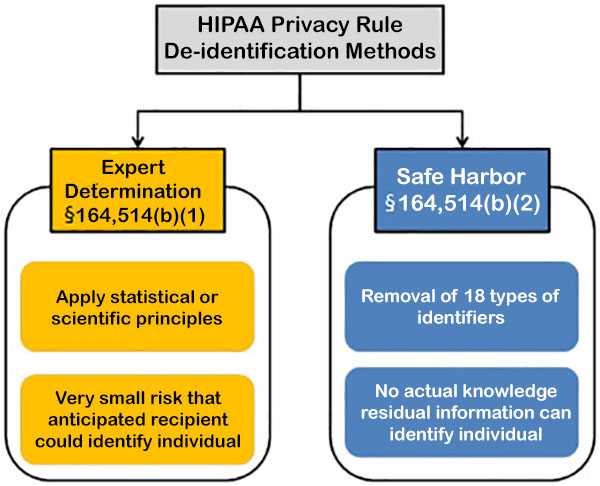

Source: HHS Methods for De-Identification of PHI

Figure 1. Methods to achieve de-identification in accordance with the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Click here to view text version

Expert determination is a formal determination by a qualified expert. This individual possesses appropriate knowledge of and experience with generally accepted statistical and scientific principles and methods for rendering information not individually identifiable. He/she will apply such principles and methods, determine the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is a subject of the information; and document the methods and results of the analysis that justify such determination.

Safe harbor is the removal of specified individual identifiers as well as absence of actual knowledge by the covered entity that the remaining information could be used alone or in combination with other information to identify the individual. The following identifiers of the individual and/or relatives, employers, or household members of the individual, are removed:

- Names

- All geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, except for the initial three digits of the ZIP code

- All elements of dates (except year) for dates that are directly related to an individual, including birth date, admission date, discharge date, death date, and all ages over 89 and all elements of dates (including year) indicative of such age, except that such ages and elements may be aggregated into a single category of age 89 or older

- Telephone numbers

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers

- Fax numbers

- Device identifiers and serial numbers

- E-mail addresses

- Web Universal Resource Locators (URLs)

- Social security numbers

- Internet Protocol (IP) addresses

- Medical record numbers

- Biometric identifiers, including finger and voice prints

- Health plan beneficiary numbers

- Full-face photographs and any comparable images

- Account numbers

- Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code

- Certificate/license numbers

Even when both methods are properly applied, the de-identified data does retain some risk of identification. Although the risk is very small, there is a possibility that de-identified data could be linked back to the identity of the patient to which it corresponds. To obtain more in-depth guidance on the two methods to achieve de-identification in accordance to the HIPAA Privacy Rule, refer to the Guidance on Satisfying the Expert Determination Method and Guidance on Satisfying the Safe Harbor Method.

For a policy framework for electronic health information exchange, refer to the Nationwide Privacy and Security Framework for Electronic Exchange of Individually Identifiable Health Information.

Privacy, integrity, security and confidentiality of the EHDI-IS

Individually identifiable health information should be protected with reasonable administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to ensure confidentiality, integrity, and availability as well as prevent unauthorized or inappropriate access, use, or disclosure.

Terms such as privacy, confidentiality, and security often are subject to varying interpretations. In this manual, we will use definitions from 45 CFR §164.304.

Definitions

Privacy

Privacy is generally “defined as the right of an individual to keep oneself and one’s information concealed or hidden from the unauthorized access and view of others” (Harman et al., 2012). Privacy also refers to the capacity to control when, how, and to what degree information about oneself is communicated to others. In the context of an EHDI system where patients are infants and young children, privacy may be defined as the right of the patient’s parents/legal guardian to hold their child’s information in secret and free from the knowledge of others. The information that is shared as a result of the clinical relationship is confidential and must be protected.

Integrity

Integrity means that the data or information has not been altered or destroyed in an unauthorized manner. Data integrity is a critical aspect of the design, implementation and usage of any data system that stores, processes, and retrieves data. Data integrity refers to the overall completeness, accuracy and consistency of data over its entire life cycle.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality is the promise that identifying information will not be disclosed without consent (except as allowed by law). Identifying information represents any information, including but not limited to demographic information that will identify or may reasonably lead to the identification of one or more specific individuals. Disclosure of confidential data for public health purposes to a public health entity without an individual’s consent (or parent’s consent on behalf of a child) is one exception allowed by law. That this exception is allowed by law implies community consent for this sharing of confidential information with public health entities.

Security

According to the National Institutes of Standards and Technology, information security is the preservation of data confidentiality, integrity and availability. Security or security measures encompass all of the administrative, physical, and technical safeguards of an information system that control data access, integrity and availability. Administrative safeguards are administrative actions, policies and procedures to manage the selection, development, implementation, and maintenance of security measures to protect electronic protected health information and to manage the conduct of the covered entity’s workforce in relation to the protection of that information. Physical safeguards are physical measures, policies, and procedures used to protect a covered entity’s electronic information systems and related buildings and equipment from natural and environmental hazards, and unauthorized intrusion. Technical safeguards are the technology and the policy and procedures that protect electronic PHI and control access to it.

How Regulations and Legislation Impact EHDI-IS Information Sharing

Newborn Hearing Screening

The HIPAA Privacy Rule recognizes the need for public health authorities to have access to PHI in order to ensure the health and safety of the public health. Covered entities can disclose protected health information without authorization to public health authorities who are legally authorized to receive such reports for the purpose of preventing or controlling disease, injury or disability. This includes the reporting of a disease or injury, reporting vital events, such as births or deaths, and conducting public health surveillance, investigations, or interventions. Under §164.502(a)[2] of the Privacy Rule, signed consent is not needed for public health authorities to share newborn hearing screening information. A covered entity is permitted to use or disclose protected health information to the individual or for the treatment, payment, or health care operations, as permitted by and in compliance with §164.506. Hence, personal information can be shared for public health purposes (e.g., surveillance of newborn hearing screening outcomes) without signed consent. Since EHDI is considered a public health authority, EHDI programs can obtain personally identifiable screening information without signed consent from hospitals and health care providers who perform the screening. Hospitals may also provide hearing screening information to primary health providers and diagnosticians without signed consent to facilitate treatment. For more information on uses and disclosures to carry out treatment, payment, or health care operations (§164.506), refer to the Electronic Code of Federal Regulations website.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99) is a Federal law that protects the privacy of student education records. FERPA does not impact the release of hearing screening information gathered from hospitals or other health entities. However, this changes when screening information is provided to the Part C program and becomes a part of the child’s educational record, i.e., the child enrolls in Part C. When that occurs, Part C may not share the information with entities outside of Part C without the signed consent of the parent. The application of FERPA depends on where the EHDI and Part C programs are located. For example, a jurisdictional EHDI program housed in the same agency or unit as other newborn screening, EI, and Part C may be permitted to share information for record linkage and tracking. That provides a unique arrangement in which EHDI information is shared while protecting each child’s privacy. However, FERPA limits information sharing when the EHDI and Part C programs are not housed in the same agency or unit, e.g., the EHDI program is located in the Department of Health and the Part C program is located in the Department of Education. In such cases, sharing data between the EHDI program and Part C is more complicated.

Part C regulations do not restrict hospitals or other entities from informing Part C, EHDI, or other health care providers that the infant has not passed a hearing screening test. However, signed consent is needed when the Part C program receives any screening information. Part C participating agencies may only share personal information to implement Part C if signed consent has been obtained (unless there is a specific exception, such as the health and safety exception). If an evaluation has made upon referral, the results of the evaluations or assessments generally cannot be disclosed to a primary referral source without prior signed consent.

Diagnostic Evaluations

Under HIPAA, signed consent is not needed for public health authorities to share diagnostic information with EHDI. Personal information can be shared to monitor diagnostic evaluations. However, FERPA requires signed parental consent if the diagnostic information is contained in the child’s educational record. A school or Part C provider must have signed consent to share diagnostic information with any stakeholder, including EHDI. No prior written authorization is needed to refer a child with a confirmed hearing loss to the Part C program. However, Part C providers cannot share diagnostic information with nonparticipating agencies without obtaining prior signed consent from parents unless there is a specific exemption.

Early Intervention Services

The eligibility requirements for enrollment into early intervention services varies across jurisdictions. As a result, different publicly and privately funded programs may qualify as Part C providers. It is important for EHDI programs to refer children with or suspected hearing to Part C, and Part C programs to notify EHDI about services that are being provided (refer to Part C of IDEA). Children enrolled in Part C are required to have an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) that delineates all the services that will be provided, including services outside of the Part C system. The IFSP must be signed by the family and all providers including the child’s medical home provider.

HIPAA requirements do not typically apply to how Part C information is shared with EHDI and/or other health providers. Providers are allowed under HIPAA to share information for facilitating the provision of health care with EHDI or other health care providers without signed consent. Although signed consent is not needed to share treatment information, records must be kept to document what information was shared.

Under FERPA, signed consent must be obtained for any education program that receives funding from the U.S. Department of Education (including Part C) to share information from an individual child’s educational record, including health information. However, educational programs are able to share general contact information, enrollment status, and dates of attendance as long as parents are notified at least annually about the program’s intent to share such information and a parent has an opportunity to object with respect to his or her child.

Signed consent is required for a Part C program to share any personal information about children enrolled in the Part C program with anyone not participating in Part C. Not even the names of children enrolled in Part C can be shared without signed consent. The Part C Privacy Regulations are more restrictive than FERPA with regard to sharing information about enrollment status with non-participating providers. As stated earlier, information sharing is less complicated when the EHDI and Part C programs are housed under the same agency or unit. Jurisdictions where EHDI and Part C are located in the same agency often define EHDI programs as Part C participating providers and hence, have shared enrollment information. The rationale for sharing information would certainly be strengthened if a memorandum of agreement exists which defines the EHDI program as a Part C participating provider. Of course, Part C can share enrollment information if there is a signed consent by the parent specifying that Part C may report specific information to the identified entities. Even if there is not signed consent for individual children, Part C may report aggregate information to EHDI, such as the number of children with hearing loss that are being served.

Families who receive any Part C service (e.g., coordination in conjunction with privately obtained services) are still considered to have been served within the Part C program. Some parents choose to have their children receive all and some of their services outside of the Part C program. If the services are provided by a program that does not receive any U.S. Department of Education funds, FERPA and Part C Privacy Regulations do not apply.

Recommended Practices for Sharing Screening, Diagnostic and EI Data

The National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management (NCHAM) published a White Paper providing information and guidance on privacy provisions. Some of the recommended practices regarding EHDI data are summarized here.

A child who does not pass a hearing screening test is referred for a diagnostic evaluation as soon as possible. A referral for an additional screening or diagnostic evaluation is the next step in receiving an appropriate hearing assessment.

Parents/guardians are informed of the screening results immediately after the hearing screening occurs, and provided copies of the screening results and referrals for their records.

Hospital staff inform parents that the screening test results will be shared with the state EHDI program and child’s health care provider to emphasize the role of EHDI and the importance of monitoring hearing status.

Standard hospital procedures are developed for sharing information with the child’s health care provider, guardians/parents, and EHDI programs and for coordinating referrals. Coordinated consent forms are developed for parents/guardians to share information with multiple providers without using multiple forms.

Families are well informed of the diagnostic results, the importance of intervention, and the next steps. They are provided with a copy of the diagnostic evaluation and any signed consent form.

Suspected or confirmed hearing loss are reported to the EHDI program to increase the probability that information is shared and to reduce the probability of infants lost to follow-up after not passing the hearing screening.

Creating a system of effective services requires the exchange of information among hospitals, audiologists, physicians, and Part C Early Intervention programs. States should have clearly articulated policies or a memorandum of agreement (MOA) between the EHDI program and each Part C program to ensure that any child with a diagnosed permanent hearing loss is connected to the Part C program as soon as possible. The MOAs should specify procedures for obtaining signed consent from parents, information to be provided, and when the information is submitted to EHDI. For specific jurisdictional statutes and laws regarding EHDI services, please go to the National Conference of State Legislatures website and the American Academy of Pediatrics website.

Organizational Policies and Procedures to Ensure Confidentiality and Security of Information

EHDI data collected by jurisdictions are subject to Federal and state laws, regulations, and statutes governing data collection and release. Organizational policies and procedures concerning EHDI data exchange and release help establish the goals of the EHDI-IS; rules of conduct for persons involved in the design, development, operation or maintenance of the EHDI-IS; outline appropriate uses and releases of information; create mechanisms for preventing and detecting violations; and set rules for disciplining offenders.

In the context of EHDI data, organizational policies and practices help properly balance patients’ rights to privacy and the need for health care providers to access relevant health information for providing care. Threats or hazards that may result in substantial harm, embarrassment, inconvenience, or unfairness for any individual whose information is maintained may be averted with administrative, technical, and physical safeguards. For example, health care organizations may allow all staff and admitting physicians to have unrestricted access to patient files, but limit the access privileges of referring physicians to their patients of record. This enables the organization to restrict the access of physicians with occasional need, but allows for unrestricted access for physicians who regularly have patients admitted or are seen at the organization. Failure to have safeguards may make patients unwilling to reveal sensitive health information to their health care providers or make such information too difficult to access when needed for care.

It is helpful to properly train all personnel to be familiar with confidentiality policies. Confidentiality agreements signed by data system administrators may contain special provisions, inasmuch as data system administrators have access to extensive confidentiality information because of their computer system responsibilities. Such provisions indicate that information is to be used only as needed for administration of the computer systems and that access granted to others should only be in accordance with established policies and procedures. Please note that these regulations will vary depending on jurisdictional statutes and regulations.

A breach of confidentiality occurs when information is released that allows an individual to be identified, and reveals confidential information about that person (information provided in trust that was not expected to be divulged in an identifiable form). To ensure that staff understand how to protect and safeguard EHDI data, you may consider training staff involved with EHDI-IS at their first employment and annually thereafter as a refresher course. Additionally, data sharing agreements can be put in place for those sharing and/or analyzing EHDI data. For more information on the CDC CSTE data release guidelines and procedures, go to the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists website.

To control the potential for indirect identification, an organization can provide special attention to the denominator and/or numerator. The possibility that a released statistic may be identified through other available information increases as the population (denominator) size decreases. For example, the likelihood of identifying a single individual in a published table is quite small if there are 5,000 infants in that specific age-race-sex group in that county. However, it is more likely that an individual might be identifiable in a smaller population. Although there is no single numeric threshold for denominator or numerator, selection of an appropriate threshold can be guided by multiple factors. These factors include sensitivity of the data; format of the data; level of detail in the data (i.e., geographic detail); likelihood that a specific record in a database may represent a unique person in a small population; and population or subgroup size (denominator or numerator). One rule combines numerators and denominators, such that data are not released if the population is less than a certain size and the number of events in a cell is less than a certain size. According to the NCHS Staff Manual on Confidentiality, the denominator should consider the proportion of population sampled (greater than 10 percent).

Health IT Security Standards

Healthcare Information Systems Security Standards Frameworks

Healthcare information system security standards are critical to ensure the confidentiality and integrity of private health information. To get more information on security standards, frameworks and configuration baselines, go to the Health Information and Management Systems Society website.

The HHS Office of Civil Rights has published guidance on privacy and security. Refer to the HIPAA Privacy Rule and Health IT to review the guidance on the following topics:

- Privacy and Security Framework: Introduction

- Privacy and Security Framework: Correction Principle and FAQs

- Privacy and Security Framework: Openness and Transparency Principle and FAQs

- Privacy and Security Framework: Individual Choice Principle and FAQs

- Privacy and Security Framework: Collection, Use, and Disclosure Limitation Principle and FAQs

- Privacy and Security Framework: Safeguards Principle and FAQs

- Privacy and Security Framework: Accountability Principle and FAQs

- The HIPAA Privacy Rule’s Right of Access and Health Information Technology

- Personal Health Records (PHRs) and the HIPAA Privacy Rule

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has published a series of papers for HIPAA-covered entities to provide insight into the Security Rule and assist with the implementation of the security standards. Refer to the HIPAA Security Information Series to review the following:

- Security 101 for Covered Entities

- Security Standards: Administrative Safeguards

- Security Standards: Physical Safeguards

- Security Standards: Technical Safeguards

- Security Standards: Organizational, Policies and Procedures and Documentation Requirements

- Basics of Risk Analysis and Risk Management

- Security Standards: Implementation for the Small Provider

If you require additional guidance, search the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website for frequently asked HIPAA questions or topics.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (2016). 2016 State Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Laws and Regulations. Retrieved at https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/state-advocacy/Documents/EHDI%20State%20Requirements%20(2016).pdf.

Grad, Frank P. The Public Health Law Manual, 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2005. http://www.himss.org/files/HIMSSorg/content/files/CPRIToolkit/version6/v7/D09_Setting_Standards_in_Healthcare_Information.pdf

Harman, L.B., Flite, C.A., Bond, K. (2012). Electronic Health Records: Privacy, Confidentiality, and Security. American Medical Association Journal of Ethics 4 (9): 712-719. Retrieved from http://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/2012/09/stas1-1209.html

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, P.L. 104-191, 119 Stat.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Research and the Privacy of Health Information: The HIPAA Privacy Rule; Nass SJ, Levit LA, Gostin LO, editors. Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. 2,The Value and Importance of Health Information Privacy. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9579/

Magnuson J.A and Fu Jr. PC (Eds). Public Health Informatics and Information Systems, 2nd Edition. Springer-Verlag: London , 2014.

McWay, Dana. (2010). Legal and Ethical Aspects of Health Information, Third Edition. New York: Cengage Learning. Chapter 9.

National Center for Health Statistics (2004). NCHS Staff Manual on Confidentiality. Retrieved from /nchs/data/misc/staffmanual2004.pdf

National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management. (May 2008). The Impact of Privacy Regulations: How EHDI, Part C & Health Providers Can Ensure That Children & Families Get Needed Services. Retrieved from http://www.infanthearing.org/privacy/docs/PrivacyWhitePaper.pdf.

Partnership for Public Health Law (2016). Legal Issues Related to sharing Clinical Health Data with Public Health Agencies. Retrieved from http://www.astho.org/Public-Policy/Public-Health-Law/Legal-Issues-Related-to-Sharing-Clinical-Health-Data-with-Public-Health-Agencies/.

Solove, D. (2013).HIPAA Turns 10. Analyzing the Past, Present and Future Impact. Journal of AHIMA 84, no.4 (April 2013): 22-28.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHSa), Office for Civil Rights. (2003). Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/privacysummary.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHSb), Office for Civil Rights. (2003). Summary of the HIPAA Security Rule. Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/srsummary.html.

United States Health and Human Services. (2007). Office of Civil Rights – HIPAA. Retrieved August 31, 2016, from http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa.

Washington, L. (2010). “From Custodian to Steward: Evolving Roles in the E-HIM Transition.”Journal of AHIMA. (Volume 81, no.5: 42-43).

- Page last reviewed: July 12, 2017

- Page last updated: July 12, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir