Career Fire Fighter/Emergency Medical Technician Dies In Ambulance Crash - Texas

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2003-05 Date Released: October 29, 2003

SUMMARY

On January 19, 2003, a 28-year-old male career fire fighter/emergency medical technician (EMT) [the victim] died when the ambulance he was riding in crested a hill and was struck head-on by an oncoming vehicle. The victim was riding restrained by a three-point lap and shoulder safety belt on the passenger side while enroute to an emergency medical call. Following the collision, both vehicles caught fire and the victim was entrapped. The driver/paramedic was transported by ambulance to a local hospital where he was treated for numerous injuries and discharged four days later. The victim was pronounced dead at the scene and was transported to the office of the medical examiner.

Although there is no evidence that the following recommendations would have prevented this fatality, they are being provided as a reminder of good safety practice.

NIOSH investigators concluded that as a matter of prudent safety operations fire departments should:

-

provide defensive driver training to all emergency vehicle operators

-

ensure that all drivers are trained and certified in emergency vehicle operations

-

develop standard operating procedures for responding to or returning from an emergency call and monitor to ensure their use

-

ensure that the load carrying capacity of all apparatus is equal to or less than the Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR)

Incident vehicle

INTRODUCTION

On January 19, 2003, a 28-year-old male career fire fighter/EMT died when the ambulance he was riding in was struck head-on by a civilian motorist. On January 21, 2003, the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On February 20, 2003, two safety and occupational health specialists from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated the incident. The NIOSH team interviewed the Chief, members of the department, and the city Fire Marshal. They visited the crash site and reviewed standard operating guidelines (SOGs), fire department pictures, the State Department of Public Safety accident report, training records of the victim, and the death certificate.

Background The combination department is comprised of 28 career and 17 volunteer fire fighter/EMTs, and serves a population of approximately 31,000 in an area of about 891 square miles.

Equipment The ambulance (Medic 3) involved in this incident was a 1995 Type IIIa ambulance body that was installed on a 1995 cutaway chassis with an automatic 7.3 liter turbo-diesel engine. The gross vehicle weight listed for the vehicle was 10,500 pounds. Following the incident, the ambulance was weighed by the Texas Department of Public Safety and was found to weigh 11,800 pounds without crew or patients. Fire department records show Medic 3 had 312,657 total miles as of January 2003. It was equipped with an Anti-lock Braking System and three-point lap and shoulder seat belts. It was previously owned and had been purchased by the department in 2002. Medic 3 was current with the State required annual inspection, and maintenance logs were maintained and up-to-date.

Street Conditions/Weather The ambulance was traveling on a State two-lane roadway. The road is comprised of asphalt with a paved shoulder. There are single east and westbound lanes that are marked with perimeter fog lines. Due to limited visibility because of the roadway grade, the westbound lane is designated as a no-passing zone and is marked by a solid yellow center line. There is a broken center line upon reaching the crest of the hill indicating it is permissible to pass if travelling eastbound. The road has a posted speed limit of 65 mph.

The incident occurred at 0630 hours which was approximately one hour before sunrise. The weather was clear with a temperature of about 29° F. The road surface was dry with no loose foreign material.

Training The department complies with State regulations which require 468 hours of training before becoming a fire fighter. The victim completed the department fire fighter training requirements including National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Fire Fighter Level I and II, Hazmat, Apparatus Operation, Live Fire, and Search & Rescue. He also had completed 260 hours of emergency medical technician training which qualified him as an intermediate-level EMT. He had been working as an EMT for eight years and had been with this department for six months.

The driver had been a paramedic/fire fighter for ten years and had also been with the department for approximately 6 months. He had completed an eight-hour driving class offered by the fire academy and had a valid Class B drivers license which is required by the State to drive a fire apparatus. There are no State licensing prerequisites for fire fighters or emergency personnel who drive ambulances.

aA Type lll ambulance is a specialty van that has a walk-through from the driver compartment into the patient area.

INVESTIGATION

On January 19, 2003 at 0608 hours, dispatch received a request for an ambulance to respond to a vehicle crash. At 0609 hours, Medic 5 was dispatched. After receiving reports from the scene regarding the severity of the incident, Medic 5 requested a back-up ambulance. Medic 3 was assigned to the call.

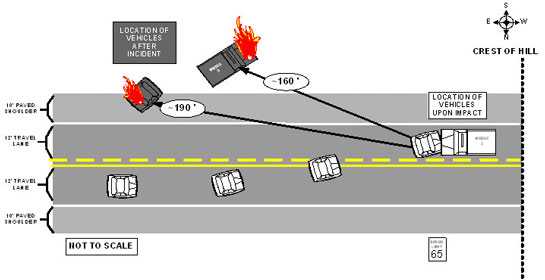

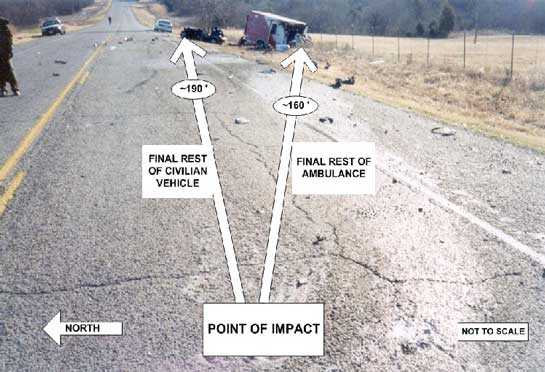

At 0626 hours, Medic 3 notified dispatch that they were departing the station. After leaving the station, they travelled eastbound on a two lane State road. According to the State Fire Marshal’s report, the ambulance was responding with emergency lights and siren activated at a speed of approximately 60 to 65 miles-per-hour. The section of road where the incident occurred is fairly straight and level when travelling eastward, with the exception of an uphill grade about four miles from the station. Immediately upon reaching the crest of this grade, the ambulance was hit head-on by a westbound vehicle that had crossed to the left of center and travelled into the eastbound lane of traffic (Diagram). After impact, the ambulance continued to travel east for approximately 160 feet coming to rest facing southwest just off of the eastbound shoulder. The victim was entrapped in the cab. The civilian’s vehicle traveled approximately 190 feet eastward coming to a stop facing northeast on the eastbound shoulder (Photo). Witnesses reported that both vehicles caught fire within minutes after they came to a final stop. Due to the lack of pre-collision skid marks at the scene, the State Department of Public Safety investigation determined there was no evidence that the brakes had been applied by the ambulance or the civilian’s vehicle prior to impact. The cause of the crash is cited by the investigative report as driver inattention and travelling to the wrong side of the road by the civilian driver. The driver was the lone occupant in the vehicle and was also killed in the incident.

In spite of his injuries, the paramedic who was driving the ambulance managed to free himself from the wreckage and records show that at 0634 hours he radioed dispatch for assistance. He then used a fire extinguisher in an attempt to douse the flames and gain access to the victim, however, heat from the fire in the cab forced him to retreat. Fire department and EMS personnel arrived on the scene and transported the driver/paramedic to a local hospital where he was treated for his injuries and discharged four days later. At 0750 hours the victim was pronounced dead at the scene and then transported to the office of the medical examiner.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The Medical Examiner established the cause of death for the victim as blunt force injuries.

Although there is no evidence that the following recommendations would have prevented this fatality, they are being provided as a reminder of good safety practice.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should provide defensive driver training to all emergency vehicle operators.1

Discussion: Sound defensive driving skills are one of the most important aspects of safe driving. Defensive driver training should address the basic concepts of defensive driving, including:

Anticipating Other Drivers’ Actions

The driver/operator should know the rules that govern the general public when emergency vehicles are on the road. Most laws or ordinances provide that other vehicles must pull toward the right and remain at a standstill until the emergency vehicle has passed. This does not guarantee that people will follow this procedure. Some drivers may panic at the sound of an approaching siren; others may be unable to hear the siren due to radios, closed windows, or loss of hearing; while others may simply ignore warning signals.

Intersections are the most likely place for an incident to occur. When approaching an intersection, the driver/operator should slow the emergency vehicle to a speed that allows a complete stop in the intersection if necessary. The emergency vehicle should be brought to a complete stop if obstructions, such as buildings or trucks, block the driver/operator’s view of the intersection. The emergency vehicle should only proceed if the driver can account for all lanes and ascertains that it is safe to proceed.

Visual Lead Time

Visual lead time interacts directly with reaction time and stopping distances. As stated in the International Fire Service Training Association (IFSTA), Fire Department Pumping Apparatus Handbook; by “aiming high in steering” and “getting the big picture” it is possible to become more keenly aware of conditions that may require slowing or stopping. The driver/operator is responsible for 360-degree driving.

Braking and Reaction Time

Speed directly affects the distance required to stop a vehicle. A driver/operator should know the total stopping distance of the emergency vehicle/apparatus. The total stopping distance is the sum of the driver/operator reaction distance and the vehicle braking distance. The driver reaction distance is the distance a vehicle travels as the driver is transferring the foot from the accelerator to the brake pedal after perceiving the need for stopping. The braking distance is the distance the vehicle travels from the time the brakes are applied until it comes to a complete stop.

Combating Skids

Avoiding conditions that lead to skidding is as important as knowing how to correct skids once they occur. The most common causes for skids are traveling too fast for road conditions, failing to properly appreciate weight shifts of heavy emergency vehicles/apparatus, and failing to anticipate obstacles. Proper maintenance of tire air pressure and adequate tread standards for tires are crucial for skid prevention.

Evasive Tactics

During an evasive maneuver, drivers’ hands should not leave the steering wheel. Drivers should not lean or sway back and forth in the seat, and they should use their arms to steer the emergency vehicle/apparatus. Drivers should look ahead of the stopped vehicle, concentrating on where they want to be. In the event of a panic stop by a vehicle ahead, drivers should pass the vehicle on the left side because the driver’s likely next move is to pull to the right, as is generally required by law.

Weight Transfer

The effects of weight transfer must be considered in the safe operation of emergency vehicles/apparatus. Weight transfer occurs as the result of physical laws which state that objects in motion tend to stay in motion; objects at rest tend to remain at rest. Whenever a vehicle undergoes a change in velocity or direction, weight transfer takes place relative to the severity of the change.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that all drivers are trained and certified in emergency vehicle operations.1

Discussion: All fire department personnel who are expected to drive emergency vehicles should be trained in the safe operation of each emergency vehicle they will be operating. This training should be completed by following a protocol of classroom (written tests and videos) and hands-on (vehicle operations/procedures) experience. Emergency vehicle operators need to realize that most driving regulations pertain to dry, clear roads. Driver/operators should adjust their speed to compensate for conditions such as wet roads, darkness, fog, or any other condition that makes normal emergency vehicle operations more hazardous.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) for responding to, or returning from, an alarm and monitor to ensure their use.1, 2, 3

Discussion: Driver/operators of emergency vehicles are regulated by State laws, city ordinances, and departmental policies. All members of the department should study and be familiar with these policies and procedures and have a thorough knowledge of the rules governing speed for emergency vehicles in their own jurisdictions and the jurisdictions of their mutual aid partners.

The department SOPs state that when responding to emergencies, “it shall be the duty of the operator of any authorized emergency vehicle to drive with due regard for the safety of all persons.” Texas transportation codes state that “authorized emergency vehicles may exceed the maximum speed limit when responding to an emergency, as long as the operator does not endanger life or property.” The State Department of Public Safety report did not list the ambulance speed as a causal factor in this incident.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that the load carrying capacity of all apparatus is equal to, or less than, the Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR).4

Discussion: The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration states that “It is very dangerous to drive any vehicle whose load carrying capacity has been exceeded. Too much weight in a vehicle can cause difficulty steering and braking. It can also compromise a vehicle’s safety by causing the tires to wear more quickly and unevenly and suspension parts and axles to wear more quickly. In extreme cases, overloading may cause catastrophic failure of any of these components.” Load carrying capacity is defined as the Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR) minus the unloaded weight of the vehicle. The Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR) is assigned to the vehicle by the manufacturer.

The Gross Vehicle Weight Rating of the ambulance involved in the incident was listed as 10,500 pounds. Following the incident, Medic 3 was weighed by representatives from the Texas Department of Public Safety and was found to weigh 11,800 pounds without crew or patients, however, there is no evidence in their report that this disparity contributed to the incident or the fatality.

REFERENCES

-

International Fire Service Training Association [1999]. Pumping apparatus driver/operator handbook 1st ed. OK: Oklahoma State University, Fire Protection Publications.

-

National Fire Protection Association [1977]. NFPA 1451, Standard for a fire service vehicle operations training program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

-

Texas Transportation Codes, Chapter 546, Subchapter A, Section 546.001, operation of authorized emergency vehicles and certain other vehicles. [http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/Docs/TN/htm/TN.546.htm#546.001]. (Link updated 1/8/2013) Date accessed: February 21, 2006.

-

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration website: www.nhtsa.gov. Accessed 08/27/2003. (Link Updated 1/16/2013)

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Virginia Lutz and Nancy T. Romano, Safety and Occupational Health Specialists, NIOSH, Division of Safety Research, Surveillance and Field Investigation Branch.

Diagram. Aerial view of incident scene

Photo. Incident Site

This page was last updated on 11/06/06

- Page last reviewed: November 18, 2015

- Page last updated: October 15, 2014

- Content source:

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Division of Safety Research

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir