Career Fire Fighter Dies in Wind Driven Residential Structure Fire - Virginia

Revised June 10, 2008 to clarify Recommendation #2

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2007-12 Date Released: May 16, 2008

SUMMARY

On April 16, 2007, a 24-year-old male career fire fighter (the victim) was fatally injured while trapped in the master bedroom during a wind-driven residential structure fire. At 0603 hours, dispatch reported a single family house fire. At 0609 hours, the victim's ladder truck was second to arrive on scene. Fire was visible at the back exterior corner of the residence. Noticing cars in the driveway, no one outside, and no lights visible in the house, the lieutenant from the first arriving engine called in a second alarm. A charged 2 ½" hoseline was stretched to the front door by the first arriving engine crew. The engine crew stayed at the door with the attack line while the cause of poor water pressure in the hoseline was determined. The victim and his lieutenant, wearing their SCBA, entered the residence through the unlocked front door. With light smoke showing, they walked up the stairs to check the bedrooms. The victim and lieutenant cleared the top of the stairs and went straight into the master bedroom. With smoke beginning to show at ceiling level, the victim did a right-hand search while the lieutenant with thermal imaging camera (TIC) in-hand checked the bed. Suddenly the room turned black then orange with flames. The lieutenant yelled to the victim to get out. While verbal communication among the crew was maintained, the lieutenant found the doorway and moved toward the stairs. He ended up falling down the stairs to a curve located midway in the staircase. The lieutenant tried to direct the victim to the stairs verbally and with a flashlight. As the wind gusted up to 48 miles per hour, the wind-driven fire and smoke engulfed the residence. The incident commander (IC) ordered an evacuation and the lieutenant was brought outside by the engine and rescue company crews. The ladder truck lieutenant received burns on his ears and right index finger. At 0614 hours, the rescue company officer issued a Mayday followed by the victim's Mayday. With protection from hose lines, several attempts were made by the engine and rescue company crews to reach the second floor. On the third attempt the stair landing was reached but the ceiling started collapsing and flames intensified. At 0621 hours, due to the intensity of the fire throughout the structure, all fire fighters were evacuated, operations turned defensive, but the incident continued in rescue mode. At 0657 hours, the victim was found in the master bedroom partially on a couch underneath the front windows.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that standard operating procedures (SOPs) for size-up and advancing a hoseline address the hazards of high winds and gusts

- ensure that primary search and rescue crews either advance with a hoseline or follow an engine crew with a hoseline

- ensure that staffing levels are sufficient to accomplish critical tasks

- ensure that fire fighters are sufficiently trained in survival skills

- ensure that Mayday protocols are reviewed, modified and followed

- ensure that water supply is established and hoses laid out prior to crews entering the fire structure

- ensure that fire fighters are trained for extreme conditions such as high winds and rapid fire progression associated with lightweight construction

Additionally, municipalities should:

- ensure that dispatch collects and communicates information on occupancy and extreme environmental conditions

Although there is no evidence that the following recommendation could have specifically prevented this fatality, NIOSH investigators recommend that fire departments:

- ensure that radios are operable in the fireground environment

INTRODUCTION

On April 16, 2007, a 24-year-old male career fire fighter (the victim) was fatally injured while trapped in the master bedroom during a residential structure fire. On April 17, 2007, the fire department, U.S. Fire Administration (USFA), and the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this fatality. On May 6 - 9, 2007, a General Engineer and a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated the incident. Photographs of the incident scene were taken and meetings were conducted with the Battalion Chief of Health and Safety (fire department's Investigating Team Leader), Fire Marshal, and an IAFF representative. Interviews were conducted with officers and fire fighters who were at the incident scene. The NIOSH investigators reviewed the department's standard operating guidelines (SOGs), the officers' and victim's training records, photographs of the incident scene, written witness statements, the coroner's report, and a weather station report. At the request of the fire department, NIOSH examined and evaluated the victim's SCBA. The SCBA was examined component by component to determine conformance to the NIOSH approved configuration. The SCBA was too damaged to test performance. (see Appendix)

Fire Department

The combination department has nineteen fire stations, three administrative worksites, a warehouse, and a training facility. A total of 1,478 fire and rescue personnel (452 career and 1,026 volunteer) serve a population of about 384,000 residents in a geographic area of about 348 square miles.

Personal Protective Equipment

At the time of the incident, the victim was wearing personal protective equipment consisting of turnout coat and pants, gloves, a helmet, hood, SCBA with an integrated PASS device, and he carried a radio. Given the condition of the victim's SCBA, the NIOSH post-incident evaluation could not determine if the SCBA performance contributed to the fatal incident. (see Appendix).

Apparatus and Personnel

Dispatch reported a single family house fire at 0603 hours.

- On scene at 0608 hours:

- Engine #12 [E12] – Lieutenant (LT#1), engine operator, and a fire fighter

- On scene at 0609 hours:

- Truck #12 [T12] – Lieutenant (LT#2), truck operator, and two fire fighters (one the victim)

- FireMedic #12 [M12] – Lieutenant and a fire fighter

- On scene at 0610 hours:

- Rescue #10 [R10]– Lieutenant, driver operator, and three fire fighters

- Engine #10 [E10] – Technician II (Acting Officer), engine operator, and a fire fighter

- On scene at 0611 hours:

- Battalion Chief (Incident Commander (IC))

- On scene at 0612 hours:

- Engine #20 [E20] – Captain, engine operator, engine operator in training, and two fire fighters

- Ambulance #10 [A10] – Lieutenant and two fire fighters

- Safety #02 - Safety Officer

- On scene at 0618 hours:

- Engine #2 [E2] – Lieutenant, engine operator, and two fire fighters

Training/Experience

The victim had completed National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Fire Fighter Level I and II training, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), Critical Incident Stress Management, Hazmat Operations, Fire Fighter Survival Skills I & II, Infection Control and several other technical courses. The victim was a career fire fighter with one year of fire fighting experience.

The Incident Commander had completed Intermediate and Advanced National Incident Management System training, Intermediate and Advanced Incident Command System Courses, several HAZMAT courses, and various other administrative, personnel and technical courses. The Incident Commander is a career fire fighter with 24.5 years in the fire service at the time of the incident

Lieutenant #1 (LT#1) had completed Fire Fighter 1 and 2, Fire Officer 1, Incident Officer, several HAZMAT courses, Fireground Tactics, and various other administrative and technical courses. LT#1 is a career fire fighter with 8 plus years in the fire service at the time of the incident.

Lieutenant #2 (LT#2) had completed Fire Fighter 1 and 2, Fire Officer 1 and 2, Fire Fighter Survival Skills 1 and 2, Advanced Fire Fighter Safety Skills, several HAZMAT courses, and various other administrative and technical courses. LT#2 is a career fire fighter with 8 years in the fire service at the time of the incident.

The Safety Officer had completed Fire Fighter 1, 2, and 3, Fire Officer 1 and 2, Field Officer, Incident Officer, Fire Fighter Survival Skills 1 and 2, several HAZMAT courses, and various other administrative and technical courses. The Safety Officer is a career fire fighter with a total of 16.5 years in the fire service at the time of the incident.

Building Information

The building was an approximately 6000 square foot, two-story plus finished walkout basement, non-sprinklered residential structure that was constructed of wood framing with vinyl siding and a brick veneer front on the exterior. The residence had a large 700 square foot wood deck that ran three quarters the length of the rear of the structure on the first floor (C-side). The roof consisted of wood rafters with fiberglass shingles over oriented strand board sheathing (see Photo1).

|

|

Photo 1. A-side of the structure where the victim entered. The victim was found in the second floor master bedroom above the bay window. |

Weather

At the time of the incident, the conditions were overcast with an approximate temperature of 45 degrees Fahrenheit and a measured sustained wind speed of 25 miles per hour (mph) from the Northwest with wind gusts up to 48 mph.

INVESTIGATION

On April 16, 2007, a 24-year-old male career fire fighter (the victim) was fatally injured while trapped in the master bedroom during a wind-driven residential structure fire. At 0603 hours, dispatch reported a single family house fire. At 0608 hours, the victim's ladder truck (T12) was second on the scene directly behind engine 12 (E12). The crews encountered fire in the B/C exterior corner of the residence underneath and along the deck on the first floor on the C-side on the structure. The wind was blowing at speeds of 25 to 48 mph. The residence was located at the top right side of a drainage where the wind was directed onto the C-side of the house. The lieutenants from E12 and T12 (LT#1 and LT#2, respectively) walked around opposite sides of the structure and met in front to discuss the size-up. Noticing cars in the driveway, no-one outside, and no lights visible in the house, LT#1 called in a second alarm. (Note: A neighbor drove to the residence and woke the residents. He walked them to another neighbor’s house and walked back to move his vehicle in anticipation of the fire department’s arrival. No-one relayed to the fire department that the residents were out of the house until after interior operations were underway.)

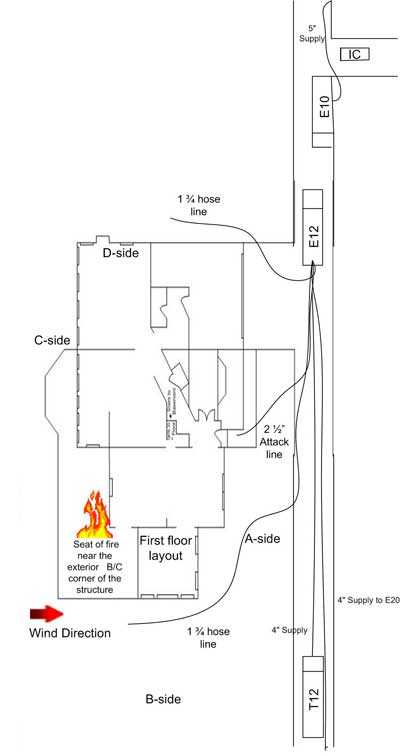

A charged 2 ½" hoseline was stretched to the front door from E12 by the E12 crew. LT#2 and the victim donned their SCBA while waiting to enter the structure. The victim tried the door, which was unlocked, so the victim and LT#2 walked into the foyer. E10 arrived on scene and was instructed by LT#1 to pull 300 feet of 1 ¾" hose from E12 in case it would be needed in the rear. At 0611 hours, with a light haze of smoke visible on the first floor, the T12 crew walked up the stairs to check the bedrooms. The E12 crew was delayed at the door with the attack line due to poor water pressure. LT#1 straightened out several kinks in the hose prior to entering the structure. At the top of the stairs, LT#2 and the victim encountered smoke banked down 3 feet from the second floor ceiling and went to the D-side of the residence towards the master bedroom. At 0611 hours, a Battalion Chief arrived on scene and assumed incident command. E20 arrived on scene and was instructed by the IC to pull 200 feet of 1 ¾" hose from E12 and cover the D-side exposures. (see Diagram#1)

LT#2 and the victim came to a set of double doors. The right door was open and they entered the master bedroom. With smoke showing at ceiling level, the victim did a right-hand search and LT#2 with thermal imaging camera (TIC) in-hand checked the bed. Suddenly the room turned black then orange with flames. LT#2 yelled to the victim to get out. While verbal communication among the crew was maintained, LT#2 found the doorway and crawled towards the stairs, falling to the curve located midway in the staircase. LT#2 communicated verbally and visually (via a flashlight) in an attempt to direct the victim to the stairs. LT#2 had been burned on his ears and right index finger. (Note: Personal protective equipment (PPE), such as hood and gloves were properly worn. However, the helmet liner was not properly down over the ears. The PPE received direct flame impingement and heat exposure.)

LT#1 and his crew along with the R10 crew were still at the front door which had slammed closed. When the door was re-opened, fire engulfed the doorway and LT#1 started yelling for LT#2 and the victim to come down the stairs. LT#1 noticed the severe change in the fire conditions in the stairway and requested an emergency evacuation. At 0613 hours, the wind-driven fire and smoke engulfed the residence. Fire was coming out of the eaves on the D-side of the structure. The E20 crew was flowing water on the D-side and the E10 crew was flowing water on the A-side of the residence, but the wind hampered the attack. Several ladders were thrown on the A and D-sides to the second floor, and on the C-side deck to the first floor, but the high winds and extreme heat made it difficult to stabilize the ladders against the building.

|

Diagram #1: Apparatus and hoseline location at time of incident |

The engine operator from E12 blew the air horn for 10 seconds to signal an evacuation. The IC gave a follow-up order to evacuate over the fireground channel. Concurrently, the R10 crew located LT#2 in the staircase area and brought him outside. At 0614 hours, LT#2 informed them that the victim was near the stairs. The R10 lieutenant issued a Mayday. It was shortly followed on the radio by the victim's Mayday. Two lines, a 2 ½" and a 1¾", were flowing on the A-side of the structure with minimal impact. (Note: From the beginning of the incident, low water pressure in two hoselines was an issue. Removing kinks in the hoses helped somewhat, but pressure problems persisted. It was undeterminable if the resultant low pressure was at the hydrant, engines, and/or due to hoseline deployment.)

At 0615 hours, LT#1 and a R10 fire fighter made it to the top of the stairs, but heat pushed them down. Several attempts were made by the E12 and R10 crews to go back up to the second floor. On the third attempt to ascend the staircase, and the second time the landing was reached, the ceiling started collapsing and flames intensified.

At 0621 hours, the Safety Officer, seeing the intensity of the fire throughout the structure, instructed the IC to call for another evacuation. The engine operator from E12 blew the air horn for a second time. At this point, the incident turned to a defensive attack, but rescue mode continued. At 0621 hours, the E2 crew was designated as the RIT and entered the C-side of the structure with a 1 ¾" hoseline to search for the victim in case a floor collapse had occurred.

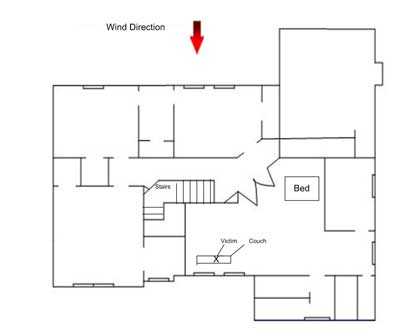

At 0631 hours, additional crews attempted to re-enter and search for the victim, but they were unable to reach the second floor due to intense heat and fire conditions. At 0634 hours, command requested dispatch of a third alarm. At 0643 hours, crews with TICs in hand were able to reach the second floor, but due to structural collapse and high-heat conditions, access to second floor areas was limited. (Note: The victim's PASS was never heard by fire fighters on the fire ground. Due to extreme heat damage, post incident testing was not possible.) At 0657 hours, the victim was found in the master bedroom partially on a couch underneath the bedroom A-side windows. (see Diagram #2)

|

Diagram #2. Location of victim on second floor in master bedroom of fire structure |

Cause of Death

The coroner listed the cause of death as thermal and inhalational injuries.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure that standard operating procedures (SOPs) for size-up and advancing a hoseline address the hazards of high winds and gusts

Discussion: Fire departments should develop SOP's for incidents with high-wind conditions including defensive attack if necessary. Weather can be considered as critically important when at the extreme, and relatively unimportant during normal conditions.1 Wind has a strong effect on fire behavior which includes supplying oxygen, reducing fuel moisture, and exerting physical pressure to move the fire and heat. Wildland fire fighters are very familiar with these effects of wind on the rate at which fire spreads. According to Dunn, "When the exterior wind velocity is in excess of 30 miles per hour, the chances of conflagration are great; however, against such forceful winds, the chances of successful advance of an initial hose line attack on a structure fire are diminished. The firefighters won't be able to make forward hoseline progress because the flame and heat, under the wind's additional force, will blow into the path of advancement". 2

Fire fighters should change their strategy when encountering high wind conditions. An SOP should be developed to include obtaining the wind speed and direction, and guidelines established for possible scenarios associated with the wind speed and the possible fuel available, similar to that in wildland fire fighting.2 When the interior attack line has little or no effect on the fire, the line should be withdrawn and a second hoseline should be advanced on the upwind side of the fire. This method may require the use of an aerial ladder or portable ladder, if safety permits.2

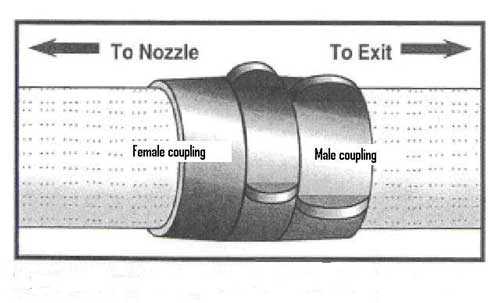

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that the primary search and rescue crews either advance with a hoseline or follow an engine crew with a hoseline

Discussion: Hoselines can be the last line of defense, and the last chance for a lost firefighter to find egress from a burning building. According to the USFA Special Report: Rapid Intervention Teams and How to Avoid Needing Them, the basic techniques taught during entry level fire fighting programs describe how to escape a zero-visibility environment using only a hoseline.3 However, as years elapse from the time of basic training, fire fighters may overlook this technique. Exiting a structure in zero visibility should be simple, fast and easy for a fire fighter with a hoseline. A fire fighter operating on a hoseline should search along the hose until a coupling is found. Once found, the fire fighter can "read" the coupling and determine the male and female ends. The IFSTA manual Essentials of Fire Fighting teaches that the female coupling is on the nozzle side of the set and the male is on the water side of the set. In most cases, the male coupling has lugs on its shank while the female does not. Once oriented on the hose, a fire fighter can follow the hoseline in the direction away from the male coupling which will take you toward the exit.4 There are a number of ways that fire hose can be marked to indicate the direction to the exit, including the use of raised arrows and chevrons that provide both visual and tactile indicators. Fire departments may use a variety of techniques to train fire fighters on how to identify hoseline coupling and the direction to the exit, based on the model of hose used by the department. The key point is that this training needs to be conducted and repeated often so that fire fighters are proficient in identifying the direction to the exit in zero visibility conditions while wearing gloves, the hose entangled, and with various obstructions present. This procedure should be incorporated into SOPs, trained upon, and enforced on the fireground.

|

Diagram #3. Hose couplings will indicate the direction toward the exit. Adapted from IFSTA Essentials of Fire Fighting, 4th Edition. |

In this incident, the truck crew went into the master bedroom doing a search without a hoseline. The engine crew with the hoseline was still at the front door when the truck crew went into the bedroom. Seconds later heavy smoke and flames blew through the upstairs hallway. The fire department's SOGs allow for the primary search and rescue crew not to have a hoseline as long as they are within sight of a crew with a hoseline. However, situations arise where conditions change in seconds preventing a fire fighter from following the hoseline to safety unless it is immediately available.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure that staffing levels are sufficient to accomplish critical tasks

Discussion: The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1710 Standard identifies the minimum resources for an effective fighting force to perform critical tasks. These tasks include establishing water supply, deploying an initial attack line, ventilating, performing search and rescue, and establishing a RIT, etc. NFPA 1710 recommends that the minimum staffing levels for an engine company to perform effective and efficient fire suppression tasks is four. 5

In this case, the first arriving engine (E12) was staffed with a lieutenant, an engine operator and a fire fighter. They stretched a charged 2 ½" attack line to the front door of the involved building for the initial attack. It is extremely difficult for a two man crew (Lieutenant and fire fighter) to advance or operate a 2 ½" hoseline without assistance. For large diameter hoselines a 3 or 4 man operation significantly increases mobility and efficiency. Had the attack line been a 1 ¾" hoseline, they would have been much better able to rapidly advance a charged line up the stairs.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are sufficiently trained in survival skills

Discussion: Fire fighters trapped or disoriented inside a room should be trained to rapidly locate doors and windows in order to escape. This is a skill that every interior structural fire fighter should possess and is typically taught in Firefighter Survival Skills I & II classes. Understanding when to self-rescue, and when to stay in a location to be rescued are critical. Fire departments should provide periodic refresher training to ensure fire fighters can effectively apply this training in different scenarios.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should ensure that Mayday protocols are reviewed, modified and followed

Discussion: Fire fighters must act promptly when they become lost, disoriented, injured, low on air, or trapped.6-10 First, they must transmit a distress signal while they still have the capability and sufficient air. The next step is to manually activate their PASS device. To conserve air while waiting to be rescued, fire fighters should try to stay calm and avoid unnecessary physical activity. If not in immediate danger, they should remain in one place to help rescuers locate them. They should survey their surroundings to get their bearings and determine potential escape routes, and stay in radio contact with Incident Command and rescuers. Additionally, fire fighters can attract attention by maximizing the sound of their PASS device (e.g., by pointing it up in an open direction), pointing their flashlight toward the ceiling or moving it around, and using a tool to make tapping noises.

A crew member or other fire fighter who recognizes a fellow fire fighter is missing or in trouble should quickly try to communicate with the fire fighter via radio and, if unsuccessful, initiate a mayday for that fire fighter providing relevant information as described above.

Department protocol requires that when a Mayday is transmitted, the IC must either personally handle the situation or designate another officer to do so. Part of "handling" a mayday is to communicate with the trapped or lost fire fighters and with any other fire fighters or officers involved. The IC or designated officer must communicate the emergency to all fireground personnel to minimize extraneous radio communication and designate another radio channel for normal fireground operations.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should ensure that the water supply is established and hoses laid out prior to crews entering the fire structure

Discussion: Successful fire suppression and fire fighter safety depends upon discharging a sufficient quantity of water to remove the heat being generated and provide safety for the interior attack crews. When advancing a hoseline into a fire structure, air should be bled from the line once it is charged, and before entering the structure.4 Fire fighters should continually train in establishing a water supply, proper hose deployment, and advancing and operating hoselines to ensure successful interior attacks.

In this incident, after the 200 feet of 2 ½" attack line and 300 feet of 1 ¾" hoseline were deployed from E12, there were complaints of low water pressure in both lines. The officer from E12 removed some kinks from the 2 ½"attack line which had a positive effect on the pressure. The pressure at both the E12 and the supply pumper E20 supposedly reported no fluctuations. There may have been a combination of factors contributing to low water pressure, such as fluctuating residential water pressure, pressure problems at one or both engines, and/or supply line issues. There was insufficient information in this incident to make a determination as to the cause of low water pressure.

Recommendation #7: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained for extreme conditions such as high winds and rapid fire progression associated with lightweight construction

Discussion: Training is one of the most important steps in fire fighter safety. Fire fighters must strive to retain information and skills that are presented in training.2 Training provides the necessary tools and fundamental knowledge to keep a fire fighter safe from injury. Just taking the training is not enough; the fire fighter needs to use their skills/information routinely on the fireground or at an actual emergency. Time is necessary to actually become proficient in those skills which are necessary for operational success in the field. In this era of new lightweight construction, training procedures covering strategy and tactics in extreme operational conditions, such as high winds and lightweight building construction (i.e., materials and design) are needed for all levels of fire fighters. Lightweight constructed buildings fail rapidly and with little warning, complicating rescue efforts. 11 The potential for fire fighters to become trapped or involved in a collapse may be increased. There are twenty-nine actions fire fighters can take to protect themselves when confronted with buildings utilizing lightweight building components as structural members. They range from looking for signs or indicators that these materials are used in buildings (such as, newer structures, large unsupported spans, and heavy black smoke being generated) to getting involved in newer building code development.11

Additionally,

Recommendation #8: Municipalities should ensure that dispatch collects and communicates information on occupancy and extreme environmental conditions

Discussion: The dispatch center should be aware of extreme environmental conditions on an hourly basis. Local weather forecasts and conditions are ready available in various media forms. When extreme weather conditions are present or the possibility exists, this information should be transmitted to the responding station when the call goes out. In addition, if the 911 caller does not relay any information about the occupancy of the fire structure, the dispatcher should explicitly ask the caller if they know if the structure is occupied.

Although there is no evidence that the following recommendation could have specifically prevented this fatality, NIOSH investigators recommend that:

Recommendation #9: Fire departments ensure that radios are operable in the fireground environment

Discussion: The fireground communications process combines electronic communication equipment, a set of standard operating procedures, and the fire personnel who will use the equipment. To be effective, the communications network must integrate the equipment and procedures with the dynamic situation at the incident site, especially in terms of the environment and the human factors affecting its use. The ease of use and operation may well determine how consistently fire fighters monitor and report conditions and activities over the radio while fighting fires. Fire departments should review both operating procedures and human factors issues to determine the ease of use of radio equipment on the fireground to ensure that fire fighters consistently monitor radio transmissions from the IC and respond to radio calls.12 The need to have properly functioning equipment during fire operations is critical.

In this incident, several fire fighters commented that radios were malfunctioning due to water shorting out the lapel microphone. However, the victim's radio was heard loud and clear during his mayday, along with several communications describing his believed location and request for water due to the extreme heat.

REFERENCES

- Brunacini, A V [1985]. Fire Command. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Dunn V (1992). Safety and survival on the fireground. Saddlebrook, NJ: Fire Engineering Books and Videos.

- USFA [2003]. Rapid Intervention Teams and How to Avoid Needing Them-SPECIAL REPORT. USFA–TR-123, March 2003.

- International Fire Service Training Association [1998]. Essentials of Fire Fighting, 4th ed. Stillwater, Ok: Fire Protection Publications, Oklahoma State University.

- NFPA (2004). NFPA 1710: Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Angulo RA, Clark BA, Auch S [2004]. You Called Mayday! Now What? Fire Engineering, September issue.

- Clark BA [2004]. Calling a mayday: The drill. [http://www.firehouse.com]. Date accessed: November 2004.

- DiBernardo JP [2003]. A missing firefighter: Give the mayday. Firehouse, November issue.

- Sendelbach TE [2004]. Managing the fireground mayday: The critical link to firefighter survival. http://www.firehouse.com/node/73134. Date accessed: January 2008. (Link updated 9/19/2011 - No longer available 10/4/2012)

- Miles J, Tobin J [2004]. Training notebook: Mayday and urgent messages. Fire Engineering, April issue.

- Smith J (2002). Strategic and Tactical Considerations on the Fireground. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; pages 185-190.

- Fire Fighter's Handbook [2000]. Essentials of Fire Fighting and Emergency Response. New York: Delmar Publishers

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Matt Bowyer, General Engineer, and Virginia Lutz, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Division of Safety Research at NIOSH. Vance Kochenderfer, NIOSH Quality Assurance Specialist, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, conducted an evaluation of the victim's self-contained breathing apparatus. An expert technical review was conducted by Battalion Chief of Safety John J. Salka, Jr., New York City Fire Department.

APPENDIX

Summary of Status Investigation Report

NIOSH Task No. TN-15210

Background

As part of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, the Technology Evaluation Branch agreed to examine and evaluate one Mine Safety Appliances 4500 psi self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

This SCBA status investigation was assigned NIOSH Task Number TN-15210. The submitter was advised that NIOSH would provide a written report of the inspections and any applicable test results.

The SCBA, sealed in a corrugated cardboard box, was delivered to the NIOSH facility in Bruceton, Pennsylvania on May 25, 2007. Upon arrival, the sealed package was taken to the Firefighter SCBA Evaluation Lab (Building 108) and stored under lock until the time of the evaluation.

SCBA Inspection

The package was opened and the SCBA inspection was performed on June 20, 2007. The SCBA was inspected by Vance Kochenderfer, Quality Assurance Specialist, of the Technology Evaluation Branch, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL), NIOSH. The SCBA was examined, component by component, in the condition as received to determine its conformance to the NIOSH-approved configuration. The entire inspection process was videotaped. The SCBA was identified as a Mine Safety Appliances (MSA) model; however, the damage was too extensive to determine the exact type.

The unit is extremely fire-damaged. Most of the plastic, rubber, and fabric components of the SCBA have been consumed. No performance testing could be conducted on the unit.

Personal Alert Safety System (PASS) Device

An ICM 2000 Plus Personal Alert Safety System (PASS) device was incorporated into the pneumatics of the SCBA. During the inspection, the PASS device could not be activated. The case was opened and representatives of MSA were able to retrieve stored data from the unit, and the last five uses are presented in Appendix II of the full Status Investigation Report. The data indicate that the unit’s battery was exhausted six minutes into the last use while the cylinder pressure was 3350 psi and the internal temperature 130°F. From the limited data available there is no indication of unusual performance of the SCBA.

Summary and Conclusions

An SCBA was submitted to NIOSH for evaluation. The SCBA was delivered to NIOSH on May 25, 2007 and inspected on June 20, 2007. The unit was identified as an MSA 4500 psi SCBA, but the exact model and NIOSH approval number could not be determined. The SCBA has suffered severe fire damage and is not functional.

It is difficult to draw conclusions about the unit given its state. The cylinder valve was found to be fully open and the cylinder empty, which would be consistent with the SCBA being used to cylinder exhaustion. Data retrieved from the ICM 2000 Plus PASS device do not suggest any malfunction during the last recorded use.

In light of the information obtained during this investigation, the Institute has proposed no further action at this time. Following inspection and testing, the SCBA was returned to the package in which it was received and stored under lock in Building 108 at the NIOSH facility in Bruceton, Pennsylvania, pending return to the submitter.

Due to the extensive damage to the unit, it does not appear possible for it to be returned to service and it should be replaced.

This page was last updated on 5/14/08.

- Page last reviewed: November 18, 2015

- Page last updated: October 15, 2014

- Content source:

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Division of Safety Research

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir