Career Fire Fighter Dies While Conducting a Search in a Residential House Fire Kansas

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2010-13 Date Released: January 18, 2011

Revised Feb 14, 2011 to correct typographic errors in Recommendation #3

Executive Summary

On May 22, 2010, a 33-year-old male career fire fighter (the victim) died while conducting a search in a residential house fire after vomiting, removing his facepiece, and inhaling products of combustion. A captain and the victim entered the 6,000 square foot residential structure with an uncharged 1 ¾ hoseline to perform search and rescue operations for an elderly occupant and a dog, while an attack crew began fire suppression operations in another part of the structure. After locating and extricating the dog, the captain and the victim continued the search in increasingly heavy black smoke. The victim became separated from the captain after he vomited, clogging his nose cup. The victim tried to clear his mask and verbally called out that he was in trouble. The captain called a Mayday and immediately began searching for him. Two rapid intervention teams (RITs) also searched for the victim. The victim was found approximately 11 minutes later and approximately 24 feet from where he was last seen. The RIT crew removed him from the structure to the front yard where paramedics performed medical care. The victim was transported to the local medical center where he was pronounced dead. After the incident it was determined that the elderly occupant was not at home.

|

Residential House Post Incident |

Contributing Factors

- Fire fighter became ill causing a self-contained breathing apparatus emergency and a separation from his captain

- The location of the victim was not immediately known

- Fire growth contributed heavy smoke, zero visibility and heat conditions.

Key Recommendations

- Develop, implement, and train on a procedure that addresses what to do if the self- contained breathing apparatus becomes inoperable due to a clogged nose cup, such as with vomitus

- Ensure that fire fighters are trained on primary search and rescue procedures which include maintaining crew integrity, entering structures with charged hoselines, and following hoselines in low visibility

- Ensure that fire fighters are trained and retrained on Mayday competencies

- Ensure that staffing levels are appropriate to perform critical tasks

Additionally, state and local governments should:

- adopt and enforce requirements for automatic fire sprinkler protection in new buildings.

|

Uncharged Hoseline at Front Door |

Introduction

On May 22, 2010, a 33-year-old male career fire fighter (the victim) died while conducting a search in a residential house fire after vomiting, removing his facepiece, and inhaling products of combustion. On May 24, 2010, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On June 7-10, 2010, a general engineer and a safety and occupational health specialist from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program traveled to Kansas to investigate this incident. The NIOSH investigators conducted an opening meeting with the fire chief, a battalion chief, and members of the Eastern Kansas Task Force (investigators from several eastern Kansas counties that serve as a pooled resource for large or complex fire scene investigations). The NIOSH investigators visited the incident scene and conducted interviews with officers and fire fighters who were at the incident. The NIOSH investigators reviewed the fire departments standard operating guidelines, officers and fire fighters training records, dispatch audio tapes, the county medical examiners autopsy report, death certificate and the Eastern Kansas Taskforce report.

Fire Department

This nonunion career fire department has 3 stations with 55 uniformed members who serve a population of approximately 60,000 within an area of about 42 square miles. All department members work a 24 hour duty shift with 24 hours off, and department members may be assigned to a fire apparatus for the entire 24-hour shift. The fire department currently has 5 engines, 2 aerial ladders, and a heavy rescue truck. Specialty units consist of swift water, ice rescue, hazardous materials, and technical rescue teams.

All fire department apparatus are maintained by the citys fleet maintenance division with annual testing of fire apparatus and ambulances conducted by qualified vendors. All advanced life support ambulances are provided by a county service.

The fire department has written policies and procedures and periodic training, which are available to all department members within their stations. Policies and procedures on incident command structure, personnel accountability system, and Mayday were in place and training records were provided.

Training and Experience

Table #1 lists the training and experience of the primary fire fighters involved in the incident.

| Fire Fighter | Training Courses | Years experience |

|---|---|---|

Victim |

Fire Fighter I and II, Fire Inspector I, Fire Service Instructor I, Fire Officer I, Swiftwater Rescue I, Swiftwater/Flood Rescue Technician, Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) Standardized Awareness, Ice Rescue, and numerous other administrative and technical courses. Specific training on Maydays during drills was reported by fire department. |

6 |

Captain #1 (C#1) |

Fire Fighter I, Incident Safety Officer, Fire Officer I, Fire Service Instructor I and II, Hazardous Materials, Incident System (IS) 100 and 200, Associate of Arts Degree in Fire Service Administration, Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), and various administrative and technical courses. |

14 |

Captain #2 (C#2) |

Fire Fighter I, II and III; Fire Officer I and II; Leadership I, II, and III; Fire Instructor I; Firefighter Safety and Survival; IS 100, 200, and 700; High Angle rescue; Associate of Arts Degree in Fire Service Administration; EMT; and various other administrative and technical courses. |

26 |

Captain #3 |

Fire Fighter I, II and III; Fire Officer II; Leadership I, and II; Fire Instructor I; IS 200 and 700; EMT; ICS 200, 300, and 400; numerous Hazardous Materials classes; Instructor Train-the-Trainer; and various other administrative and technical courses. |

25 |

Battalion Chief |

Fire Fighter I and II; Fire Officer I; Train-the-Trainer; Fire Instructor I; Incident Command system (ICS) 100, 200, 300,400, and 700; Ice Rescue; Rescue Systems; Trench Rescue; Confined Space/Structural Rescue I; Associate of Arts Degree in Fire Service Administration; and various other administrative and technical courses. |

25 |

Battalion Chief |

Fire Fighter I; Fire Officer I; Fire Instructor I; Incident Safety Officer; Leadership I and II; Arson Investigation; Firefighter Safety and Survival; IS 100, 200, and 800; ICS 200; Bachelor of Public Administration; Fire Service Management; EMT; Numerous Hazard Materials and Fireground Tactics courses; and various other administrative and technical courses. Instructed at the Regional School on numerous occasions. |

28 |

Note: Fire Fighter 1 and 2 qualifications met the criteria for National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1001, Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, Fire Fighter I and Fire Fighter II.1

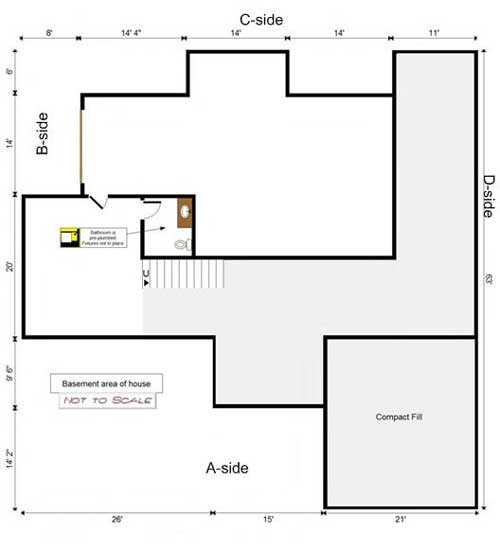

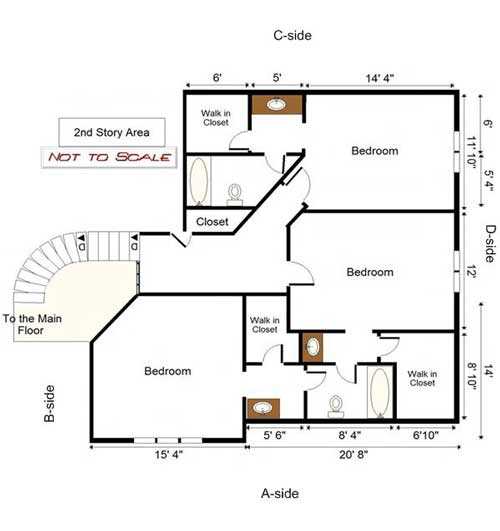

Structure

The incident involved a non-sprinklered 6,000 square foot two-story single family residence with a full basement that was built in 1998 (). Currently, the state of Kansas does not require residential structures to be sprinklered. The lower level included a walk-out basement and secondary lower see Photo 1 level garage. The main floor consisted of a great room, dining room, kitchen, breakfast room, master bedroom and bath with make-up room, utility room, office and a two car garage. The top floor consisted of three bedrooms and 2 full bathrooms. The structure had 2 x 6 exterior wood frame construction, solid 2x 10 wood floor joists, and 2 x 8 roof rafters. The exterior was stucco with wood trim and the roof had Spanish style cement tiles. The interior walls were 2 x 4 wood studs covered with ½ sheetrock and the floor coverings were primarily carpeting throughout the house. The basement/secondary garage area contained shelves of paint and cans of refinishing materials along the interior south wall and 3 cars. The basement area contained an unfinished half bath and large area containing the hot water heater and furnace (see Diagrams 1, 2, and 3).

|

Photo1: Residential House |

Personnel and Equipment

An automatic fire alarm was received at 2052 hours from the residence and a ladder truck company was dispatched per the standard protocol. Three minutes later dispatch called in a residential structure fire. The fire department dispatched on first alarm a battalion chief, three engines, a quint, and a medic unit, in addition to the truck dispatched on the automatic alarm. Table 2 identifies the apparatus and staff dispatched on the first alarm, along with their approximate arrival times on-scene (rounded to the nearest minute).

Table 2. First Alarm Equipment and Personnel Dispatched

|

Resource Designation

|

Staffing | On-Scene (rounded to minute) |

|---|---|---|

Truck 71 (TR71) |

Captain Engineer / operator Fire fighter |

2058 hrs |

Battalion Chief 71 (IC) |

Battalion Chief |

2058 hrs |

Engine 71 (E71) |

Captain |

2101 hrs |

Medic 1132 (M1132) |

2 Paramedics |

2101 hrs |

Battalion Chief 91 (BC91) |

Battalion Chief |

2101 hrs |

Engine 92 (E92) |

Captain |

2103 hrs |

Engine 73 (E73) |

Captain |

2105 hrs |

Quint 72 (Q72) |

Captain |

2105 hrs |

Incident Timeline

The following timeline is a summary of events that occurred as the incident evolved on the late evening of Saturday, May 22, 2010. Not all incident events are included in this timeline. The times are approximate and were obtained by studying the dispatch records, audio recordings, witness statements, and other available information. This timeline also lists the changing fire behavior indicators and conditions reported, as well as fire department response and fireground operations. All times are approximate and rounded to the closest minute.

|

Fire Behavior Indicators & Conditions

|

Time

|

Response & Fireground Operations

|

|---|---|---|

|

Automatic fire alarm

|

2052 |

Call received for a residential fire alarm. TR71 dispatched. |

911 caller states “stuff blowing up and a house on fire.” Multiple calls coming in. |

2055

|

First alarm companies marked enroute - IC, E71, E73, E92, Q72, and M1132. Radio Channel assigned Tac 4. |

|

911 caller states smoke observed and fire in garage. TR71 reports smoke visible from highway. |

2057

|

BC91 dispatched and enroute.

|

|

2058

|

BC71 and TR71 arrived on-the-scene. Residence identified as 2 story wood frame by BC71 and TR71. |

|

|

2059

|

BC71 states fire in downstairs garage. Gas utility contacted. TR71 captain doing size-up. |

|

TR71 reports smoke from back window. |

2100

|

Neighbor states possible elderly occupant or couple and a dog inside. TR71 advises Command. |

|

|

2101

|

E71, M1132, and BC91 arrived on-the-scene. |

|

Heavy fire in B/C corner of basement. Fire starting to travel up exterior of B/C Corner. Heavy black smoke began pouring out the broken sidelite window and door entrance at ground level. Heavy smoke on first floor.

|

2103

|

TR71 crew started fire suppression at B/C corner. E92 arrived on-the-scene. E71assigned as search and rescue and making forcible entry at front door. |

|

|

2105

|

E73 and Q72 arrived on-the-scene. E92 assigned fire suppression with TR71. E71 crew found a dog in the utility room. |

|

|

2107

|

E71 captain and fire fighter (victim) handed the dog to a crew at the A-side door. Q72 assigned as secondary search and rescue crew |

|

Heavy fire in basement/lower level garage. Fire being knocked down and coming back. A lot of steam conversion. Exterior fire at B/C corner up to the eaves. |

2110

|

C#1 (E71) calls Mayday for victim BC71 orders another tactical channel on radio. |

|

|

2112

|

BC71 tried to contact the victim. |

|

2113

|

BC71 confirmed Mayday called by victim’s captain. |

|

Heavy smoke and heat on second floor.

|

2114

|

IC assigned Q72 crew as rapid intervention team (RIT) and assigned E73 as a second RIT. |

|

Zero visibility and heat on second floor.

|

2119

|

2 RITs searched for victim, Q72 on the first floor and E73 on the second floor. |

|

|

2124

|

RIT locates victim. |

|

|

2125

|

BC71 ends Mayday. |

|

|

2149

|

BC71 orders defensive operations. |

Personal Protective Equipment

The victim was wearing his bunker coat and pants, gloves, hood, boots, helmet, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) with an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS), and a radio during the initial entry into the structure. The victim was found with his gloves, helmet and facepiece removed. In addition, the nose cup was found separated from his facepiece. Vomitus was found around the exhalation valves and seal of the nose cup. The National Personal Protection Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) evaluated the SCBA and the summary evaluation report is included as Appendix One. The full report can be provided upon request.

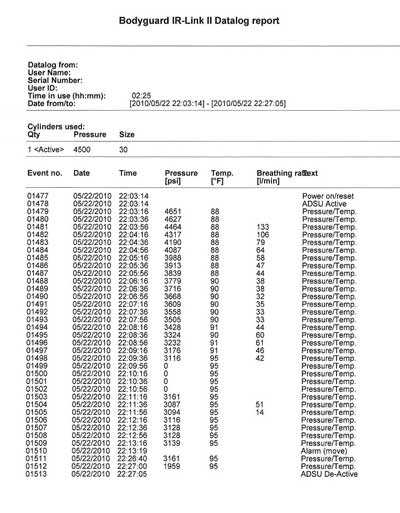

SCBA Internal Data

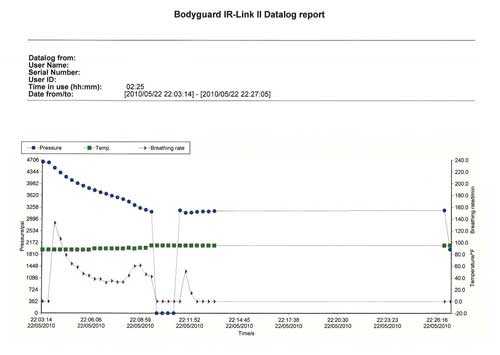

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1981, Standard for Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) for Emergency Services, 2007 edition, required SCBAs certified to that standard revision to collect and retain air management and life support data. The SCBA involved in this incident was certified to the 2002 edition of NFPA 1981 and this data collection capability had already been incorporated. This data can be collected and retained for a limited period of time when properly isolated and restricted after an incident. The fire department correctly isolated and restricted access to the SCBA which allowed NIOSH to obtain this data with the assistance of the manufacturer.

The data in Appendix Two indicates that the victim went on air upon entry into the fire structure at approximately 2103 hours. Note: The actual time on the table and the diagram indicate 2200 hours but this is due to the SCBAs internal clock being set on eastern standard time and the incident occurring in the central time zone. Approximately 6 minutes later the psi was recorded as 0 and there was no breathing rate data indicating that the victim had turned off his air and removed his mask. It is hypothesized that the victim had vomited and removed his mask, gloves, and nose cup and turned off his air in an attempt to clear the nose cup. Seconds later, he turned his air back on, took a few breaths during the next 20 seconds and went down. The integrated PASS alarm unit went into automatic full alarm 63 seconds later.

Weather

At approximately 2100 hours, the weather was clear with an approximate temperature of 81°F. The relative humidity was 60% and the wind was from the south at 15 miles per hour (mph). The State Fire Marshal reported that weather did not play an active role in the fire.2 Note: The National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) has released a report that indicates when wind speed is over 10 mph that fire departments should consider implementing procedures for a wind driven fire.3

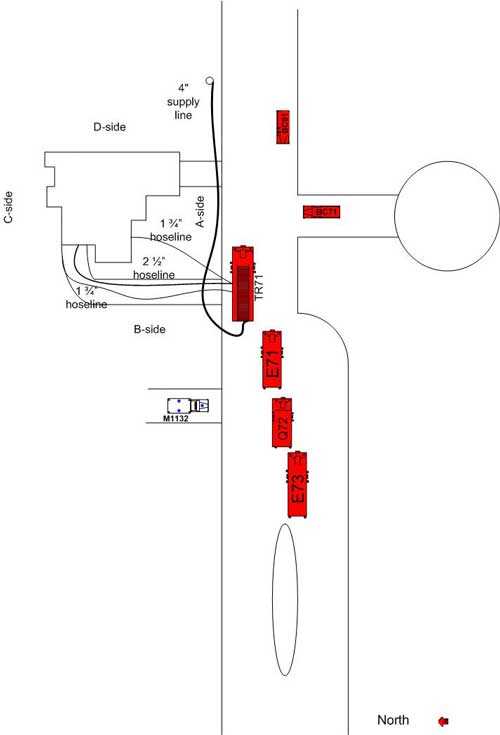

Investigation

On May 22, 2010, at 2052 hours, an automatic fire alarm dispatched Truck 71 (TR71) per normal protocol. At 2055 hours, dispatch called in a residential structure fire. First alarm companies Battalion Chief 71 (BC71), Engine 71 (E71), Engine 73 (E73), mutual aid Engine 92 (E92), Quint 72 (Q72), and Medic 1132 (M1132) were assigned. Three minutes later, BC71 and TR71 arrived on-the-scene. BC71 assumed incident command (IC) and notified dispatch of a large residential structure with heavy smoke and fire visible on the B-side. Incident command was established on the A-side of the structure in the adjoining intersection directly across the street (see Diagram 4).

A neighbor informed the IC of an elderly occupant or couple and a dog in the house. The IC assigned TR71 to perform a search of the home. The TR71 captain (C#2) had just completed a 360 degree size-up and had requested a hoseline to the B/C corner of the structure. C#2 then advised the IC of reports of an elderly occupant and a dog in the house. The IC reassigned the TR71 crew as the fire attack crew and the E71 crew as the primary search and rescue crew. The E71 captain (C#1) informed command that they would have to use forcible entry at the dead-bolted storm door and locked front door. The IC assigned arriving crews of E92 to the B/C corner to assist TR71 in fire attack and Q72 to the front (A-side) with tools to assist in forcible entry.

TR71 had connected to a hydrant approximately 50 feet east of the truck with a 4 supply line. The truck crew had a 1 ¾ hoseline going to the B/C corner and E92 had a 2 ½ hoseline off of TR71 going to the B/C corner to conduct fire suppression operations in the basement/lower level garage. The TR71 crew worked on knocking down the exterior fire on the B/C corner.

|

Photo 2: Basement/Lower Level Garage on B/C corner. |

The E92 crew made entry at the lower garage door and the heavy fire was converting the water to steam as the crews kept fighting the fire (see Photo 2).

The IC assigned mutual aid battalion chief (BC91) as the safety officer. BC91 completed a head count of the fire attack crews on the B/C corner and observed fire conditions worsening on the C-side exterior to the roof. He then headed to the A-side.

The E71 fire fighter (the victim) broke the sidelite door window adjacent to the door handles and unlocked the front door and storm door to make entry. Heavy black smoke began pouring out of the broken sidelite window and door entrance at ground level. C#1 and the victim advanced an uncharged 1 ¾ hoseline off of TR71 through the front door and began a right hand search. The victim had the hoseline between his legs with the nozzle in one hand and a thermal imaging camera (TIC) in the other; C#1 was right behind him.

The victim and C#1 crawled down a hallway to the right of the entry door, approximately 36, into a utility room where they found a dog. The victim picked up the medium size (approximately 45 pounds) dog and carried it to the front door. C#1 was directly behind him, but they had left the uncharged hoseline in the hallway. The victim handed the dog off to the Q72 captain (C#3) at the door, who in turn handed it to the TR71 operator and then to the M1132 medics.

The victim re-entered the structure and met up with C#1 just inside the door to continue the search. The Q72 crew (C#3 and 2 firefighters) entered the structure to assist in the search. The Q72 crew went straight ahead to the smoke filled staircase and had ascended about 5 steps when they heard C#1 yelling for the victim. They immediately went down the stairs and met up with C#1 in the hallway near the open entry way to a sitting room on the left. C#1 told C#3 that he heard the victim yell help me. C#1 stated the victim was right in front of him. The Q72 crew did a quick scan of the area with the TIC but saw nothing. They stepped just inside the open doorway to the left to scan when C#1 stated again that the victim was right in front of him in the hallway. The C#1 radioed a Mayday to command. C#3 requested the IC have dispatch page the victim.

In the lower level garage, the E92 crew had advanced to the cars halfway in the garage and could see an orange glow towards the D-side wall (see Photo 3).

|

Photo 3: Cars in Lower Level Garage |

The IC assigned the Q72 crew as the rapid intervention team (RIT#1). The RIT proceeded to do a right hand search on the first floor and went into the office area then into the garage where they looked underneath two cars and opened the right garage door. C#1 and C#3 searched the half bathroom and scanned the utility room with the TIC. Just as the two captains got back to the double doors to the sitting room, C#1’s low air alarm went off. The 2 RIT firefighters met back up with the captains and rescanned the sitting room with the TIC and discussed the possibility of the victim going to the basement. C#3 escorted C#1 out of the structure while his RIT crew went to the great room area past the stairway; the floor felt spongy. They proceeded down the basement stairs and did a left hand search of the A-side basement area and half bath. One of the crew thought debris was falling around them so they proceeded back up the stairs.

A positive pressure fan had been set at the front door and was running as the first RIT crew again searched the office area and proceeded back to the garage and opened another garage door. The IC assigned E73 as a second RIT and they proceeded to the second floor stairway. The second RIT with a TIC reached the second floor with zero visibility and heat, and started searching the bedrooms.

The first RIT crew went back to the sitting room and went to the right where they opened a door to a make-up room. One RIT team members flashlight hit the reflection tape on the victims bunker pants. The TIC showed the location of the victim and the crew heard his personal alert safety system (PASS) device. They radioed command that they had found the victim (see Diagram 2).

The second RIT had just reached the third second floor bedroom when they heard the radio transmission and backed out. The E92 crew had made it to the last car in the lower level garage when they heard the radio transmission and backed out.

The victim was lying on his back in the make-up room without his helmet, gloves, and facepiece on. The RIT crew him and carried him out to the yard where medic crews began taking off his gear and put him on a power cot and into Medic 1132. Inside the medic unit, they started an IV and noticed the victim was not breathing and had a faint pulse. The victim was intubated to clear his airway of vomit and soot. CPR was rendered and he was placed on a life-aid machine. The victim was transported to the hospital and later pronounced dead.

Cause and Origin

The area of origin was in the lower level garage bay along the south wall where storage shelves were present. A clock radio was the probable ignition point in the area of origin. Per the State Fire Marshal Report, the house electrical circuits and attached components could not be eliminated as a cause. The fire is listed as accidental.2

Contributing Factors

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatalities:

- Fire fighter became ill causing a self-contained breathing apparatus emergency and separation from his captain

- The location of the victim was not immediately known

- Fire growth contributed heavy smoke, zero visibility, and heat conditions.

Medical Findings

It is unknown why the victim vomited. The victim reportedly had eaten two large meals that day, lunch around 1300 hours and supper around 1700 hours. It is possible that the large meals in combination with the heavy exertion in the search and rescue efforts and the heat from the fire contributed to his vomiting.

Cause of Death

According to the death certificate, the victims cause of death was exposure to gases of combustion.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: Manufacturers should recommend and fire departments should develop, implement, and train on a procedure that addresses what to do if the self-contained breathing apparatus becomes inoperable due to a clogged nose cup, such as with vomitus.

Discussion: Self-contained breathing apparatus have undergone many changes over the past decades, one of which is the incorporation of a nose cup. The nose cup helps eliminate fogging/condensation of the facepiece lens. However, it has a very limited area of free space if a fire fighter gets sick and the potential to clog the exhalation valves is high. Depending on the manufacturer, nose cups can be removed rather quickly and the facepiece may remain fully functional providing breathable air without it. Currently, a validated best practice for an emergency training protocol could not be found for this particular scenario. An emergency training protocol should be established for the removal or clearing of the nosecup in an emergency situation for each type of SCBA. The International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) and other fire fighting agencies are currently working to develop a standardized protocol to educate and train fire fighters on how to deal with debris clogged facepieces. Any fire fighter feeling ill or nauseous should not enter an immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) environment. Any fire fighter who experiences a nauseous feeling while in a IDLH environment must immediately evacuate the IDLH environment.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained on primary search and rescue procedures which include maintaining crew integrity, entering structures with charged hoselines, and following hoselines in low visibility.

Discussion: Fire fighters should always work and remain in teams whenever they are operating in a hazardous environment.4 Team integrity depends on team members knowing who is on their team and who is the team leader; staying within visual contact at all times (if visibility is low, teams must stay within touch or voice distance of each other); communicating needs and observations to the team leader; and rotating together for team rehab, team staging, and watching out for each other (e.g., practicing a strong buddy system). Following these basic rules helps prevent serious injury or even death by providing personnel with the added safety net of fellow team members. Teams that enter a hazardous environment together should leave together to ensure that team continuity is maintained.

Successful fire suppression and fire fighter safety depends upon discharging a sufficient quantity of water to remove the heat being generated and provide safety for the interior attack crews. When advancing a hoseline into a fire structure, air should be bled from the line once it is charged and before entering the structure.4 Hoselines can be the last line of defense and the last chance for a lost firefighter to find egress from a burning building. The hoseline becomes a three dimensional pathway to exit the structure. According to the USFA Special Report: Rapid Intervention Teams and How to Avoid Needing Them, the basic techniques taught during entry level fire fighting programs describe how to escape a zero-visibility environment using only a hoseline.5 However, as years lapse from the time of basic training, fire fighters may overlook this technique. Exiting a structure in zero visibility should be possible for a fire fighter with a hoseline. A fire fighter operating on a hoseline should search along the hose until a coupling is found. Once found, the fire fighter can read the coupling and determine the male and female ends. The IFSTA manual Essentials of Fire Fighting teaches that the female coupling is on the nozzle side of the set and the male is on the water side of the set. In most cases, the male coupling has lugs on its shank while the female does not. Once oriented on the hose, a fire fighter can follow the hoseline in the direction away from the male coupling which will take them toward the exit.4 There are a number of ways that fire hose can be marked to indicate the direction to the exit, including the use of raised arrows and chevrons that provide both visual and tactile indicators. Fire departments may use a variety of techniques to train fire fighters on how to identify hoseline coupling and the direction to the exit, based on the model of hose used by the department. The key point is that this training needs to be conducted and repeated often so that fire fighters are proficient in identifying the direction to the exit in zero visibility conditions while wearing gloves, when hoses are entangled, and with various obstructions present. This procedure should be incorporated into SOPs, trained upon, and enforced on the fireground.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained and retrained on Mayday competencies.

Discussion: Fire fighters need to understand that their personal protective equipment (PPE) and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) do not provide unlimited protection. Fire fighters should be trained to stay low when advancing into a fire as extreme temperature differences may occur between the ceiling and floor. When confronted with an emergency situation, the best action to take may be immediate egress from the building or to a place of safe refuge (e.g., behind a closed door in an uninvolved compartment) and manually activate the PASS device. A charged hoseline should always be available for a tactical withdrawal while continuing water application or as a lifeline to be followed to egress the building. Conditions can become untenable in a matter of seconds. In such cases, delay in egress and/or to transmit a Mayday message reduces the chance for a successful rescue.

The victim had some drill training in Mayday best practices but did not declare a Mayday for himself. Firefighters should be 100% confident in their competency to declare a Mayday for themselves. Fire departments should insure that any personnel who may enter an IDLH environment meet the Authority Having Jurisdiction standards for Mayday competency throughout their active duty service. Presently there are no national Mayday standards for firefighters to be trained to and most states do not have Mayday standards. A Rapid Intervention Team (RIT) will typically not be activated until a Mayday is declared. Any delay in calling the Mayday reduces the window of survivability and also increases the risk to the RIT.6,7,8,9

The US Fire Administration National Fire Academy has two courses: Q133 Firefighter Safety: Calling the Mayday a self study course and H134 Calling the Mayday: Hands on Training course; they are both available on one CD free of charge from the National Emergency Training Center publication office: https://apps.usfa.fema.gov/publications/?it=0-0039 (Link updated 10/4/2012)

Any Mayday communication must contain the location of the firefighter in as much detail as possible, and at a minimum should include the division (floor) and quadrant. In this incident, a total of 12 minutes elapsed between the time the IC became aware of the missing firefighter and the Rapid Intervention Team locating the Victim. It was not clear to the IC, Safety Officer or RIT if the victim was on the first floor, second floor, or in the basement. The victim was found on Division 1 in Quadrant C in the makeup room behind a closed door. Note: Some SCBA manufacturers offer a telemetry option for their SCBA. This allows the incident command post to monitor a fire fighters air and life support data giving the IC or ICs aide an indication of a problem or possible problem.

It is imperative that firefighters know their location when in IDLH environments at all times to effectively be able to give their location in the event of a Mayday. Once in distress firefighters must immediately declare a Mayday. The following example uses LUNAR (Location, Unit, Name, Assignment/Air, Resources needed) as a prompt: Mayday, Mayday, Mayday, Division 1 Quadrant C, Engine 71, Smith, search/out of air/vomited, cant find exit. When in trouble, a firefighters first action must be to declare the Mayday as accurately a possible. Once the IC and RIT know the fire fighters location, the firefighter can then try to fix the problem, such as clearing the nose cup, while the RIT is enroute for rescue. 7

A firefighter who is breathing carbon monoxide (CO) quickly looses cognitive ability to communicate correctly and can unknowingly move away from an exit, other firefighters, or safety before becoming unconscious. Without the accurate location of a downed firefighter the speed at which the RIT can find them is diminished, and the window of survivability closes quickly because of lack of oxygen and high CO concentrations in an IDLH environment. 6,7,8

Fire fighters also need to understand the psychological and physiological effects of the extreme level of stress encountered when they become lost, disoriented, injured, run low on air or become trapped during rapid fire progression. Most fire training curricula do not include discussion of the psychological and physiological effects of extreme stress, such as encountered in an imminently life threatening situation, nor do they address key survival skills necessary for effective response. Understanding the psychology and physiology involved is an essential step in developing appropriate responses to life threatening situations. Reaction to the extreme stress of a life threatening situation, such as being trapped, can result in sensory distortions and decreased cognitive processing capability.10 Fire fighters should never hesitate to declare a Mayday. There is a very narrow window of survivability in a burning, highly toxic building. Any delay declaring a Mayday reduces the chance for a successful rescue.11

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that staffing levels are appropriate to perform critical tasks.

Discussion: The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1710 Standard identifies the minimum resources for an effective fire fighting force to perform critical tasks. These tasks include establishing water supply, deploying an initial attack line, ventilating, performing search and rescue, and establishing a RIT. NFPA 1710 recommends that the minimum staffing levels for an engine company to perform effective and efficient fire suppression tasks is four.12 In addition, a recently released study by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), Report on Residential Fireground Field Experiments, concluded that a three-person crew started and completed a primary search and rescue 25 percent faster than a two-person crew and that four or five-person crews started and completed primary search and rescue 6 percent faster than a three-person crew.13

It is essential that staffing levels are sufficient to have a dedicated RIT crew at every fireground and that any on scene assignments will not hamper the RIT team’s immediate response to the firefighter down or Mayday situation.9 The RIT crew, as well as being a dedicated crew, must have specialized rapid intervention equipment dedicated to the priorities of locating the downed firefighter, determining respiratory needs, supplying air if needed, conducting extraction from the IDLH if possible and/or protecting trapped fire fighters in place if necessary.14

The greatest enemy for the firefighter in a Mayday or RIT situation is typically time without air which means that the strictest discipline and training to reduce the loss of time is critical for the fire fighter in trouble. Many RIT operations take far longer to extricate the victim to the outside than anticipated. The battle of time without air can be minimized by establishing air (utilization of rescue air) as a prerequisite to extrication. Then the RIT crew can focus on how to get the victim out or protect them in place.

During this incident, several of the responding engines and trucks were understaffed per NFPA 1710 recommendations and a dedicated RIT crew had not been established prior to the Mayday event.

Recommendation #5: State and local governments should adopt and enforce requirements for sprinkler protection in new buildings.

Discussion: The International Code Councils International Residential Code and the NFPA 101, Life Safety Code, require sprinkler protection in all new one-and two-family dwellings and in most other properties. 15-16 Fire development beyond the incipient stage is one of the greatest hazards that fire fighters are exposed to. This exposure and risk to fire fighters can be dramatically reduced when fires are controlled or extinguished by automatic sprinkler systems. NFPA statistics show that most fires in sprinklered buildings are controlled prior to fire department arrival by the activation of one or two sprinkler heads. The presence of automatic fire sprinklers also reduces the exposure risk to fire fighters in rescue situations by allowing the safe egress of building occupants before the fire department arrives on scene. Finally, by controlling fire development, the exposure to hazards such as building collapse and overhaul operations are greatly reduced, if not eliminated.

References

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1001: Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Kansas State fire Marshal Report [2010]. Case No. 34334

- NIST [2010]. Fire Fighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Fire Conditions: 7-Story Building Experiments. NIST Technical Note 1629, April 2009. http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire09/PDF/f09015.pdf

- International Fire Service Training Association [2008]. Essentials of fire fighting and fire department operations, 5th ed. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, Oklahoma State University.

- USFA [2003]. Rapid Intervention Teams and How to Avoid Needing Them-SPECIAL REPORT. USFATR-123, March 2003.

- Clark, B.A. [2005]. 500 Mayday called in rookie school. http://www.firehouse.com/article/10498807/500-maydays-called-in-rookie-school (Link updated 10/4/2012)

- US Fire Administration [2006]. Mayday CD Q133 Firefighter Safety: Calling the Mayday and H134 Calling the Mayday: Hands on Training. Emmitsburg, MD: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Fire Administration, National Fire Academy.

- Clark BA [2008]. Leadership on the line: Firefighter Mayday Doctrine where are we now? Radio@Firehouse.com http://www.firehouse.com/podcast/10459336/leadership-on-the-line-firefighter-mayday-doctrine-where-are-we-now. (Link updated 1/28/2013)

- IAFC Safety, Health, and Survival Section [2010]. Rules of Engagement of Structural Firefighting. [http://websites.firecompanies.com/iafcsafety/files/2013/10/ROE_Poster_FINAL1.pdf]. Date Accessed: December 2010. (Link updated 1/14/2014)

- Grossman D & Christensen, L [2008]. On combat: The psychology and physiology of deadly conflict in war and peace (3rd ed.). Millstadt, IL: Warrior Science Publications.

- International Association of Fire Chiefs [2009]. Rules of Engagement for Firefighter Survival. http://www.iafc.org/operations/legacyarticledetail.cfm?itemnumber=2718; (Link updated 10/4/2012) Date accessed 9/1/10.

- NFPA [2010]. NFPA 1710: Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments. 2010 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NIST [2010]. Report on Residential Fireground Field Experiments. NIST Technical Note 1661, April 2010. http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=904607

- NFPA [2010]. NFPA 1407: Standard for Training Fire Service Rapid Intervention Crews. 2010 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- International Code Council [2009]. International Residential Code for One and Two-Family Dwellings. 500 New Jersey Avenue, NW, 6th Floor, Washington, DC 20001.

- NFPA [2010]. NFPA 101: Life Safety Code. 2010 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

Investigator Information

This incident was investigated by Matt E. Bowyer, General Engineer and Stephen Miles, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, with the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, located in Morgantown, WV. Tom Pouchot, NIOSH General Engineer, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, conducted an evaluation of the victims SCBA. An expert technical review was provided by Dr. Burton Clark, EFO, CFO, National Fire Academy and Dan N. Rossos, Lieutenant, Portland Fire and Rescue Training and Safety Division and Chairman, NFPA Technical Committee on Respiratory Protection Equipment. A technical review was also provided by the National Fire Protection Association, Public Fire Protection Division.

Disclaimer

Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites.

Summary of Personal Protective Equipment Evaluation

Status Investigation Report of One

Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus

Submitted By the

Fire Department

NIOSH Task Number 17077

(Note: Full report is available upon request)

Background

As part of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, the Technology Evaluation Branch agreed to examine and evaluate one SCBA identified as Drager Safety model AirBoss Evolution PSS 100,

4500 psi, 30-minute, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

This SCBA status investigation was assigned NIOSH Task Number 17077. The Fire Department was advised that NIOSH would provide a written report of the inspections and any applicable test results.

The SCBA, contained within a corrugated cardboard box, was delivered to the NIOSH facility in Bruceton, Pennsylvania on June 18, 2010. After its arrival, the package was taken to building 108 and stored under lock until the time of the evaluation.

SCBA Inspection

Initially, the package was opened in the NPPTL Laboratory contained in building 40 on October 27, 2010 and the unit data logger was downloaded by Drager Safety personnel and witnessed by NIOSH members. The package was then re-opened in the Respirator / SCBA Evaluation Lab (building 37) and a complete visual inspection was conducted. The SCBA was inspected on November 29, 2010 and was designated as Unit#1. This SCBA was examined, component by component, in the condition as received to determine the conformance of the unit to the NIOSH-approved configuration. The visual inspection process was documented photographically. The SCBA was identified as the Drager Safety model Air Boss Evolution PSS 100, 30 minute, 4500 psi unit, NIOSH approval number TC-13F-513. It was judged that the unit could be safely pressurized and tested.

SCBA Testing

The purpose of the testing was to determine the SCBA conformance to the approval performance requirements of Title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 84 (42 CFR 84). Further testing was conducted to provide an indication of the SCBA conformance to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Air Flow Performance requirements of NFPA 1981, Standard on Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus for the Fire Service, 1997 Edition.

NIOSH SCBA Certification Tests (in accordance with the performance requirements of

42 CFR 84):

1. Positive Pressure Test [§ 84.70(a)(2)(ii)]

2. Rated Service Time Test (duration) [§ 84.95]

3. Static Pressure Test [§ 84.91(d)]

4. Gas Flow Test [§ 84.93]

5. Exhalation Resistance Test [§ 84.91(c)]

6. Remaining Service Life Indicator Test (low-air alarm) [§ 84.83(f)]

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Tests (in accordance with NFPA 1981,

1997 Edition):

7. Air Flow Performance Test [Chapter 5, 5-1.1]

Unit # 1 was tested on November 30 and December 9, 2010.

Appendix II contains the complete NIOSH and NFPA test reports for the SCBA. Tables One and Two summarize the NIOSH and NFPA test results.

Also attached in Appendix II are the results of the download of the SCBA data logger. The data was downloaded by personnel from Drager Safety and witness by members of NIOSH.

Summary and Conclusions

A SCBA was submitted to NIOSH by the Fire Department for evaluation. The SCBA was delivered to NIOSH on June 18, 2010, the unit data logger was downloaded on October 27, 2010. The SCBA unit was then inspected on November 29, 2010. The unit was identified as a Drager Safety model Air Boss Evolution PSS 100, 4500 psi, 30-minute, SCBA (NIOSH approval number TC-13F-513). The unit suffered very minimal damage, exhibited slight signs of wear and tear, some foreign material was present on parts of the unit but the SCBA unit was generally in good condition. The cylinder valve as received was in the closed position and the cylinder gauge read approximately 0 psig. The regulator and facepiece mating and sealing areas on the unit were clean and the nose cup was separate from the facepiece and there was debris on the nosecup. The harness webbing on the unit was in good condition with no fraying or tears. The PASS device on the unit did not function initially but after several on/off cycles, the device functioned properly.

The NFPA approval label on the unit was present and readable. Visibility through the lens of the unit facepiece was good but the lens had some minor scratches.

The air cylinder on the unit had a manufactured date of 2/05. Under the applicable DOT-E-1194- 4500 exemption, the air cylinder is required to be hydro tested every 5 years, starting on or before the last day of February, 2010. A hydro requalification label was present with a date of 2/10. Therefore it appears that the cylinder was within hydro certification when last used. The unit cylinder was in good condition. This cylinder was utilized for all testing. No other maintenance or

repair work was performed on the unit at any time.

The SCBA unit met the requirements of the NIOSH Positive Pressure Test, with a minimum pressure of 0.05 inches of water. The Unit met the requirements of all of the other NIOSH tests. The unit did not pass the NFPA flow test as the Heads-Up-Display (HUD) did not function during the test. This non-functioning HUD was not investigated and the batteries were not replaced. In light of the information obtained during this investigation, NIOSH has proposed no further

action on its part at this time. Following inspection and testing, the SCBA was returned to storage pending return to the Fire Department.

If the unit is to be placed back in service, the SCBA must be repaired, tested, and inspected by a qualified service technician, including such testing and other maintenance activities as prescribed by the schedule from the SCBA manufacturer. Typically a flow test is required on at least an annual basis.

SCBA Data – Table and Diagram form

|

|

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In 1998, Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative that resulted in the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program which examines line-of-duty-deaths or on duty deaths of fire fighters to assist fire departments, fire fighters, the fire service and others to prevent similar fire fighter deaths in the future. The agency does not enforce compliance with State or Federal occupational safety and health standards and does not determine fault or assign blame. Participation of fire departments and individuals in NIOSH investigations is voluntary. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident who agree to be interviewed and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the death(s). Interviewees are not asked to sign sworn statements and interviews are not recorded. The agency's reports do not name the victim, the fire department or those interviewed. The NIOSH report's summary of the conditions and circumstances surrounding the fatality is intended to provide context to the agency's recommendations and is not intended to be definitive for purposes of determining any claim or benefit.

|

For further information, visit the program Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

This page was last updated on 12/17/2010.

- Page last reviewed: November 18, 2015

- Page last updated: October 15, 2014

- Content source:

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Division of Safety Research

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir