PHAPshots: Snapshots of Associates’ Favorite Projects

Every associate has a different story to tell about his or her time in PHAP and the unique experiences encountered along the way. PHAPshots allow associates to tell their stories—through images and words—about their favorite public health project to date.

Victor Cabada

In my first year as a public health associate, I worked for the Connecticut Department of Public Health, where I supported the state’s participation in the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). By linking information from multiple sources—medical examiners’ reports, death certificates, and law enforcement incident reports—NVDRS answers the “who, when, where, and how” of violent deaths to provide comprehensive insights about “why” the deaths occurred.

The majority of my NVDRS work involved data collection and analysis. I also worked on the implementation and use of the NVDRS Child Fatality Review module in Connecticut. This tool helps identify the circumstances that put children at risk so future interventions can better protect them. My experiences have drawn me further into epidemiology as a way to measure the health of a population, evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of interventions, and inform policies with the intention of identifying areas and populations where services are most needed. It was especially comforting to see the data and information I’d helped provide to the field being used to educate people and, hopefully, to guide development of interventions against violent deaths.

Throughout my PHAP experience, the willingness of supervisors and other staff to include me in various aspects and levels of public health—and even entertain my ideas—provided me with a really positive work environment and a rewarding experience overall. Their openness allowed me to have experiences that broadened my understanding of public health in various sectors, which in turn gave me a better perspective on how I want to serve public health in the future.

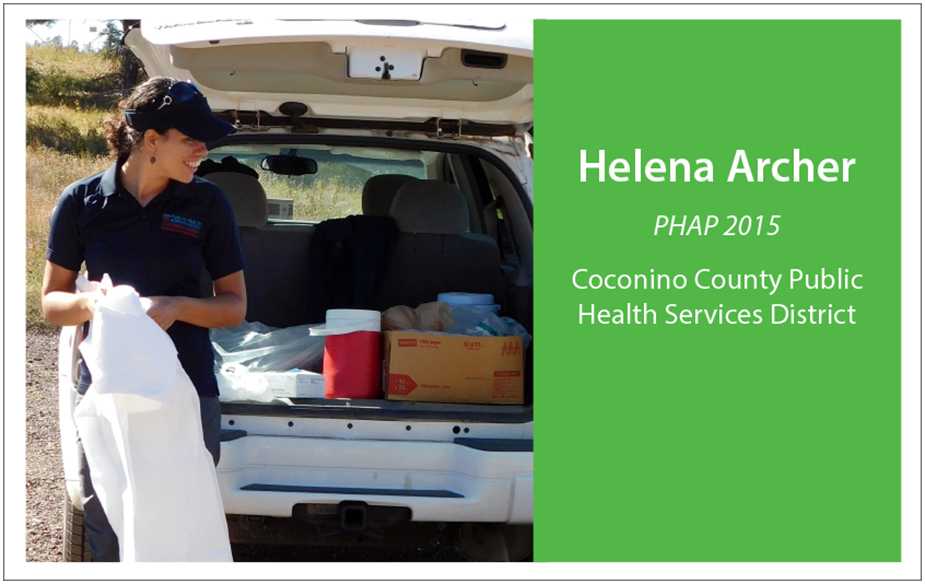

Helena Archer

In my time at Coconino County Public Health Services District in Arizona, I’ve had the opportunity to learn more about local health needs by working on interesting hands-on projects, such as a geographic analysis of injuries, which are the leading cause of death in Coconino County—at twice the national rate. As part of the epidemiology team, I spend the bulk of my time analyzing health data that support our programs and help identify gaps in care and local needs.

I’ve also been part of gathering data on an emerging public health issue—opioid abuse. I was recently asked to help our public information officer respond to media requests on opioid abuse in Coconino County and Arizona, which evolved into a full report on opioid-related deaths and hospital visits using county-level data. I was able to pull the data for the media request, research national trends and interventions for our chief health officer, and, under the guidance of our epidemiologist, create a report using death certificates and hospital data on local-level opioid abuse trends. It was very interesting to be able to work on an emergent epidemic, but it is also the type of work that challenges you in terms of the epidemiology. Opioid abuse is constantly changing, so there is some difficulty in collecting data on this problem to use in combatting it. But, that is also part of what makes it so engaging—discovering how to keep up with the data and the learning curve.

What has really made my PHAP experience special has been marrying the data with field work. For example, in the picture above, I’m suiting up with our environmental health team to dust insecticide in prairie dog burrows that had tested positive for plague. Although rare, plague is endemic in the region and causes prairie dog die-offs and the fleas left behind carry the disease, so the fleas must be killed. This work requires us to wear shoulder-to-toe protective suits and bug spray to keep from getting bitten by those remaining fleas—and potentially infected with plague.

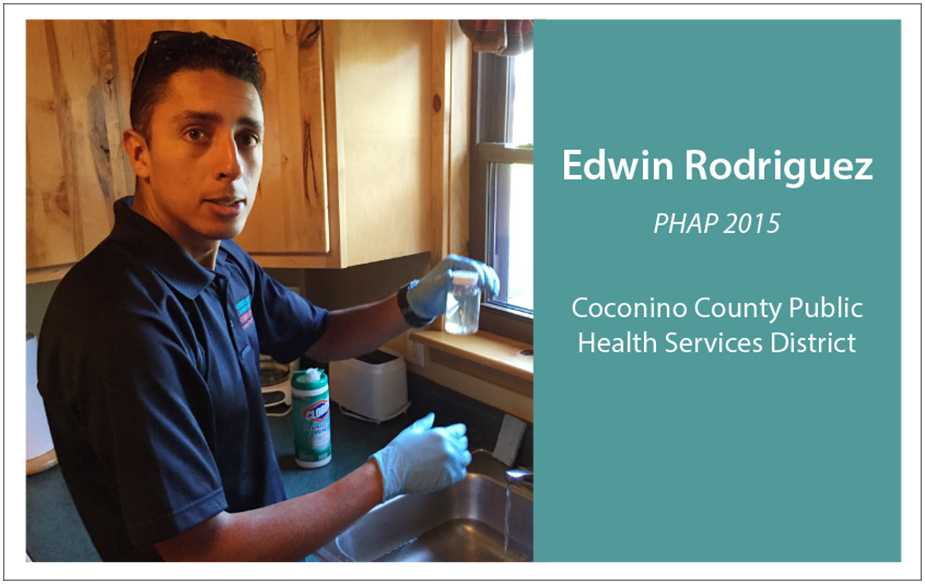

Edwin Rodriguez

As a public health associate assigned to the Coconino County Public Health Services District (CCPHSD) in Flagstaff, Arizona, I’ve been fortunate to work in a wide array of public health disciplines—and so much of it is beyond what I could have imagined! Sometimes, I’ll find myself crawling in small spaces of homes in full Tyvek® suit and respirator searching for evidence of hantavirus, while knowing there is no cure for it and that it has a 40% fatality rate. Other times, I’m advising providers about which people to test and how to test them, as well as about treating them for various infectious diseases during outbreaks.

One of my favorite field experiences was when CCPHSD’s epidemiology program partnered with environmental health specialists to investigate a waterborne outbreak at a wedding. When we extracted water samples from wells on the rental property where the wedding took place, things got complicated because the test samples had to come directly from the well instead of the spigot (pictured above). Getting samples from the well involved a lot of precision, given the extremely small size of the virus involved and the expected level of difficulty in extracting viable samples from water using an ultrafine filter. Analysis of the samples proved that a leaking well had become adulterated by a nearby septic tank, making the wedding guests very sick with gastrointestinal issues.

Although I’m assigned to work on infectious disease, I’m able to work on so much more than outbreak responses. I’ve collaborated with the Translational Genomic Research Institute for genetic monitoring of disease, the Northern Arizona University Biology Department to draw blood from the hearts of mice for research, and the Coconino County Medical Examiner’s Office to observe autopsies.

I am extraordinarily fortunate to have been a public health associate and to have had the opportunity to begin my public health career with such invaluable learning and field experiences.

Anthony Johnson

For me, the most memorable part of being a PHAP associate for the City of Minneapolis Health Department (MHD) has been working on a local healthy food access program and a national food program, simultaneously. I was a project manager for the Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance, a citywide policy requiring licensed grocery stores and small food stores to increase their community’s access to healthy foods. I was also a project specialist working on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Retail Program Standards, a nationwide quality improvement program designed to create uniformity in food regulatory programs and enhance the services they provide to the public.

The FDA program provides funds for completing projects and training to enhance adherence to nine topic areas, or standards, regarding quality and compliance in how health inspectors perform their duties. As a project specialist, I completed the self-assessment for the MHD Food, Lodging, and Pools division to identify where it can have the greatest impact on retail food safety. Next, I enrolled MHD environmental health staff in the FDA Retail Program Standards curriculum to begin the standardization process. At the same time, I developed a program to train all 18 MHD health inspectors to conduct compliance assessments for the Staple Foods Ordinance. With both projects operating simultaneously, I gained hands-on experience in the field plus administrative experience in the office.

PHAP is a training program, so I never once thought I’d be the one doing the training. But, thanks to PHAP, I got to develop my knowledge and expertise in defined areas of public health, train colleagues, and help start new programs at MHD. This entire experience has been very rewarding, particularly because my work has become a part of MHD’s standard procedures for conducting compliance assessments at all 238 licensed grocery stores in Minneapolis and for new stores in the future. My PHAP experience is the foundation for my career in public health, and I’m excited to see what’s next!.

Lauren Linde

When I started my PHAP assignment in October 2014, Los Angeles County was in the midst of a tuberculosis (TB) outbreak that had been going strong in the homeless population there since 2007. Most of my work in the Los Angeles County Public Health Department’s TB Control Program has focused on different methods of combatting the outbreak (e.g., active case finding, contact tracing, prevention strategies).

One of my most exciting projects was helping design and implement a contact investigation in a homeless shelter where many people with the outbreak strain of TB had stayed. I managed screening data for nearly 2,000 contacts from that shelter. Initially, only about 100 of these contacts could be found for screening because the homeless population is so mobile. I worked continually with data collected by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority to locate more of these individuals for TB testing. I also interviewed homeless TB patients around the county and helped start a weekly TB screening at the shelter, which has tested more than 1,000 shelter residents to date. Those who test positive for TB infection are referred for treatment, and we just started an exciting new project to offer housing to people for the duration of their treatment. I was even able to help administer the TB blood tests at the screening myself because my host site arranged for me to be certified in phlebotomy.

TB is a fascinating disease and it has been an incredibly motivating time to be involved in TB prevention—the World Health Organization recently designated it the number one cause of infectious disease-related death globally, and the annual number of TB cases in the United States increased (although slightly) in 2015 for the first time in decades. The global fight against TB has not received as much attention as the fights against diseases like HIV and malaria in recent years, so I’m hoping to see TB enter the public dialogue a bit more! I’ve loved learning about how TB affects my community by working directly with patients. I know my PHAP experience has given me a great foundation for a career dedicated to reducing disparities in infectious diseases, healthcare access, and health education.

Brittany Grear

On March 25, 2016, I served as the operations chief for the Florida Department of Health’s (FDH) Hillsborough County Tuberculosis (TB) Center’s World TB Day event—one of the most exciting opportunities of my PHAP tenure. At the event, my TB program colleagues at FDH and I provided free TB screenings. We also offered free screenings for HIV, hepatitis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis, along with select immunizations. To raise awareness about TB and to encourage people to attend the event, I did an interview with Telemundo (Telenoticias Tampa Bay) and developed a promotional flyer.

The goal of our World TB Day event was to reach underserved and at-risk populations in our community. In particular, we wanted to reach homeless persons, who can contract TB in congregate settings (e.g., homeless shelters, correctional facilities, safe havens), where disease can spread easily. For the event location, we chose the Trinity Café, a local gathering place that provides daily breakfast and lunch to hungry, homeless, and underfed residents.

During the event, participants were tested for sexually transmitted infections (68 for HIV, 79 for hepatitis, 85 for syphilis, and 83 for gonorrhea/chlamydia), 81 were tested for TB, and 41 received immunizations. Eight participants, all of whom reported being homeless and had a history of incarceration, tested positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. These participants are receiving follow-up care and treatment, or they are being encouraged to return for it.

Participating in this event was very gratifying because it afforded me the opportunity to help my host site establish, build, and strengthen its public health impact on communities in need.

Allison Napier

In January 2015, just months after I became a PHAP associate, the New Orleans City Council unanimously passed a city-wide smoke-free ordinance, which went into effect on April 22, 2015. My supervisors knew I had been working to build my health literacy skills, so they asked me to establish and chair a health literacy committee for the department. As the chairperson, I was asked to create plain language materials to help business owners understand and implement the new smoke-free ordinance. I was very excited to use my skills on such an important and impactful public health initiative, particularly one that had received widespread media attention in the months leading up to its implementation.

First, I helped translate a smoke-free fact sheet full of complex legal terms and regulations into easy-to-understand language, simplified the main messages with headings and bullets, created more white space, and removed jargon. Then, I helped to design the “No Smoking or Vaping” signs that are now permanent fixtures all over New Orleans. It is really cool to see my work everywhere I go. Finally, I was part of the outreach team that delivered the toolkits to all types of businesses and answered questions. I even received a shout-out from Mayor Mitch Landrieu on social media!

Sachiko Oshima

One of my most exciting projects with PHAP is the OutsideIn SLO campaign, a partnership between and the San Luis Obispo (SLO) County Health Department and the California Department of Public Health. The campaign’s goal is to educate our community on the effects of climate change on human health—a topic I never dreamed I’d be able to work on when I entered PHAP. Through OutsideIn SLO, we educate residents on a range of topics, from sea level rise to extreme weather, and then connect these climate change events with their subsequent health impacts.

For example, SLO residents are very concerned about California’s drought, so we explain how the effects of climate change—like increases in extreme heat events and shifting precipitation patterns—could be affecting the drought’s severity. Then, we try to show the many ways this environmental occurrence affects our community’s health: reducing our food and water supplies, lowering our air quality (and aggravating asthma and allergies), and increasing the spread of diseases like valley fever. Overall, we’ve gotten a very positive response, with many requests for more information. I love helping my adopted community!

Christine Graaf

My most memorable PHAP project was leading a hepatitis C surveillance and prevention project during my second year. The project’s overall intent was to define and characterize the population in El Dorado County that is disproportionately burdened with hepatitis C; identify prevention, education, and care resources in the county; and share this information with the public. The project was dynamic, engaging, challenging, and rewarding, and was instrumental in helping me develop leadership skills.

Through this experience, I learned how to perform effective client interviews, contact tracing, partner notification, health education, and care referrals. I also learned how to conduct surveillance activities such as phone interviews, focus groups, written surveys, and data analysis. I even got to hone my public speaking skills by giving presentations to community residents and public health professionals. It was exciting to be on the frontlines of public health, making a difference.

Julia Ritch

When I began my second-year rotation in the Epidemiology Department at Dallas County Health and Human Services Department, I thought I would be doing data analysis, patient interviews, and disease surveillance. Then suddenly on September 30, 2014, the next thing I knew I was on the front lines of the Dallas Ebola Response, working 10-hour days interviewing family and friends of the patient and performing twice-daily temperature checks.

For me, the most rewarding work of the Ebola response was interacting directly with the community contacts, including being among the first to meet with a few of the patient’s extended family members. I helped walk them through the process of temperature monitoring, addressed any physical needs they had, and provided moral support during a difficult period of stigma, fear, and uncertainty. Being able to help on the front lines of this historic public health response was an unexpected, but tremendously exciting, opportunity. This experience will always be memorable to me because it highlighted the flexibility, communication, compassion, persistence, and resourcefulness needed to accomplish public health goals.

Margo Rosner

My Baltimore City Health Department (BCHD) supervisors worked with me to design a position that let me explore my interests in health promotion and sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention. Much of this assignment involved planning BCHD’s annual Know Your Status Ball and Conference. I worked to strengthen relationships with community partners and formed new partnerships with diverse community organizations, all of whom offered services at the event. We saw a 34% increase in testing numbers from the previous year’s event!

We also got to introduce a new component of BCHD’s condom distribution program—a home-based condom delivery system. With guidance from my host site, I researched, planned, and carried out this program that let people at greatest risk for HIV and other STDs register online for monthly condom shipments. PHAP has given me a once-in-a-lifetime field experience, and my host site has given me all the support I needed to thrive there. The skills I’ve gained from PHAP are invaluable, and I am excited to build on them throughout my public health career.

Elaine Tran

The most exciting part of my PHAP assignment has been my work as a disease intervention specialist (DIS). In this role, I have been charged with performing outreach testing for HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea at community sites throughout Columbus, Ohio. To become a DIS, I trained in phlebotomy and got certified in HIV counseling, testing, and referral. I also perform surveillance and follow-up for positive cases of chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Each day, I put on my blue lab coat, pack my orange bag with my specimen collection supplies, lug my cooler with biohazard stickers on the outside, and go to a different site. These sites range from homeless shelters and recreation centers to faith-based organizations and thrift stores. I enjoy working one-on-one with each client who comes through for testing—whether they are there for a routine check or a first visit and have no idea what HIV stands for. I see myself as a resource for the people who test with me. In the little time I have with each client, my goal is to get to know them, provide them education, and refer them to services, either for sexual health or just general public health. I love doing this work and interacting with such a diverse mix of people.

Emma Prasher

As a PHAP associate, I have had many stimulating public health experiences, but I’ve most enjoyed my work in infectious diseases. While working at the Philadelphia Quarantine Station, I screened incoming air travelers for infectious diseases and helped develop a mass medication dispensing plan for the Philadelphia International Airport’s 20,000 employees. Then, in my second year of PHAP, I transitioned to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, where I investigated more than 900 influenza-associated hospitalizations and other disease outbreaks.

My most exciting experience during PHAP was being deployed to Guinea as part of CDC’s Ebola response. While in Guinea, I was part of the Infection Prevention and Control team working to set up triage systems at healthcare facilities, including the one pictured above where I’m having my temperature taken at a hospital in Conakry. I really enjoyed practicing on-the-ground public health and working with an energetic team of international public health partners. Being in Guinea was an eye-opening experience that solidified my desire to focus on global health in the future.

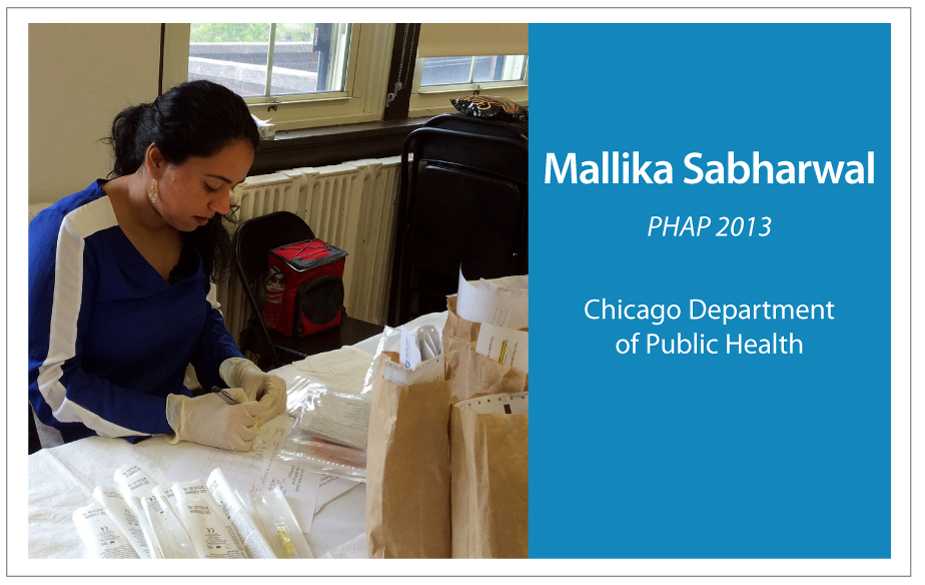

Mallika Sabharwal

In college, my mind was set on going to medical school and becoming a physician—I didn’t even know what public health was. During my final semester, I worked at a safety net clinic and was disheartened to see all the patients who had diabetes or hypertension and were simply given a prescription refill to overcome their illness. There had to be more that could be done. That was when I realized I could not solve this problem as a physician using clinical medicine—I would also need to incorporate public health principles into my practice. Through PHAP, I learned about public health and how to address health needs at a broader level.

During my assignment at the Chicago Department of Public Health, I worked in the school-based sexually transmitted infection (STI) program, where I educated high school students about STIs and tested them for gonorrhea and chlamydia. When students tested positive, I referred them to treatment locations, such as the health department’s STI clinic or a community health center. The opportunities and obstacles I encountered, like learning to communicate with youth in culturally appropriate ways, analyzing data to inform future programming, and navigating bureaucracy, taught me invaluable skills. And, by working on the program’s logistics―such as preparing urine samples for lab testing or using third-party billing to sustain the program—I learned about the infrastructure needed to support public health programs. Together, these experiences have given me a great foundation on which to build my future career as a public health physician.

Katherine Mullican

My most memorable PHAP experience was participating in the Anne Arundel County Oral Rabies Vaccination Project to immunize thousands of raccoons against rabies. I was part of one of the helicopter teams that spent the morning distributing bait containing rabies vaccine by dropping it—by hand—from the air. Using a helicopter allowed us to distribute bait in harder-to-reach areas, such as forests, much more efficiently and quickly than if we’d done it on foot. We flew at low altitudes in a helicopter with no doors, which enabled us to drop bait every few seconds.

I had never been in a helicopter before, but I was thrilled. While baiting, we were able to see the Severn River, the Bay Bridge, and downtown Annapolis. It was an unforgettable experience and a great opportunity to participate in a unique public health intervention that required us to think outside the box and overcome obstacles.

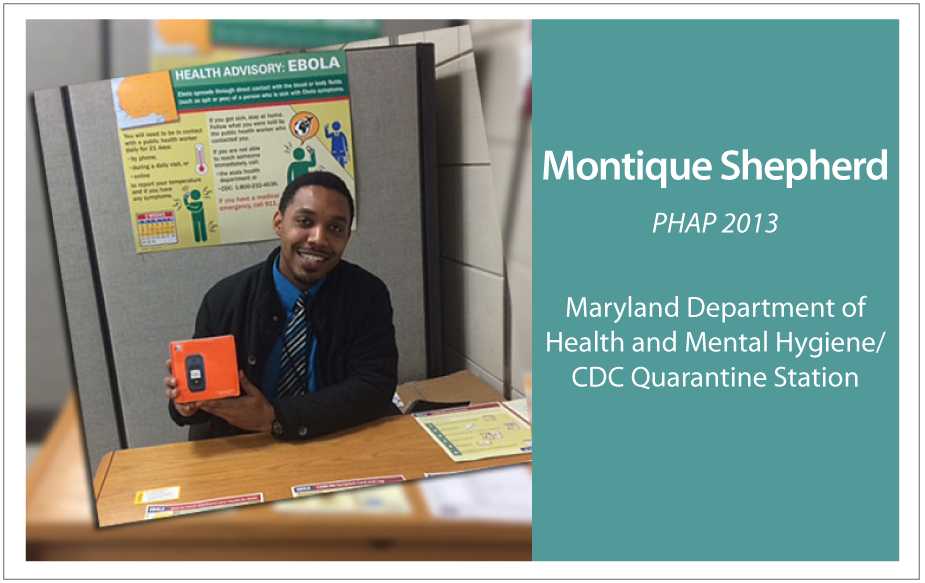

Montique Shepherd

I was working with the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Center for Immunization, preparing an online survey and conducting a multi-year assessment of school-based clinic activities in Maryland, when I was deployed to the CDC response for the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa. Suddenly, I was on a 60-day assignment at the CDC Quarantine Station at Dulles International Airport near Washington, DC.

At the Quarantine Station, I did airport surveillance, learned how to properly put on and remove personal protective equipment, and helped establish the airport’s first “Check and Report” Ebola station. I even got the opportunity to conduct care encounters―a joint effort by CDC and the US Customs and Border Protection―with international travelers at airport entry screenings. In this role, I spoke with incoming international travelers about US active monitoring protocols for Ebola and gave them tools to help them do daily health checks for the next 21 days after they entered the United States. Without PHAP, I would have never had such an extraordinary experience like this, where I have had the opportunity to learn prominent public health skills and positively impact the health of communities.

- Page last reviewed: October 11, 2017

- Page last updated: October 11, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir