Transcript

Download Slides

Elizabeth M. Ward, PhD: Hello. I am Elizabeth Ward, senior vice president of Intramural Research at the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and chair of the World Trade Center Health Program (WTCHP) Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC). Welcome to this program on "Cancer and the World Trade Center Health Program."

Joining me today is Michael Crane, director of the WTCHP Clinical Center and associate professor of preventative medicine at the Selikoff Centers for Occupational Health at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, New York. Also with me is Dr. David Prezant, chief medical officer, Fire Department of New York; special advisor to the Fire Commissioner for Health Policy; and co-director of the WTCHP, in New York, New York. Finally, with me is Mark Farfel, director of the World Trade Center (WTC) Health Registry at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene in New York, New York. Welcome to all of you.

The goals of this program are to explain why the WTCHP added cancer to the List of WTC-Related Health Conditions under the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act of 2010, which is also known as the Zadroga Act, to recognize what cancers and screenings are covered by the WTCHP, and to identify the processes for determining the WTC-relatedness of a disease in a patient with cancer suspected to be due to WTC exposure.

The James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act of 2010 established the WTCHP Scientific/Technical Advisory Committee(STAC). The act specifies 3 general areas of contributions to the WTCHP from the STAC. The act requires the administrator to seek advice from the STAC with regard to additional eligibility criteria, to identify research needs for the program, and determine whether a particular health condition should be added to the List of WTC-Related Health Conditions.1

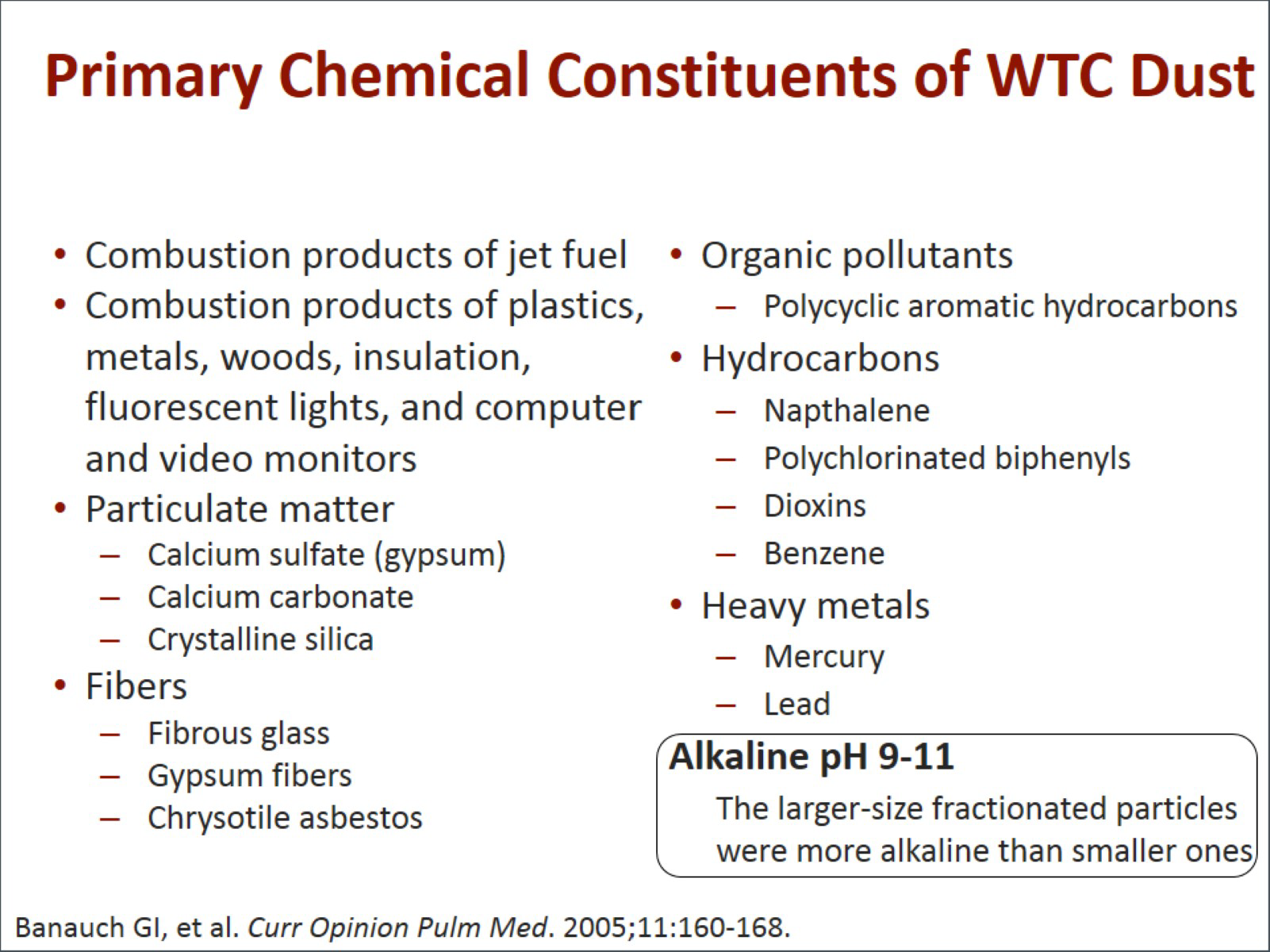

Michael A. Crane, MD, MPH: The STAC made recommendations regarding the addition of cancer to the List of WTC-Related Health Conditions. The conclusions were based primarily on the presence of approximately 70 known potential carcinogens in the smoke and dust and volatile contaminants; 15 were classified as known carcinogens; and 37 classified by the National Toxicology Program as reasonably anticipated to cause cancer in humans.2

Although exposure data are extremely limited, the high prevalence of acute symptoms and chronic conditions, as well as qualitative descriptions of the exposure conditions, provided highly credible evidence that significant toxic exposures occurred.

The next slide lists the primary chemical constituents of the WTC dust. Among the most important and notable are asbestos, benzene, and the high Ph of many of the particles, as well as combustion products, organic pollutants, hydrocarbons, and heavy metals.3

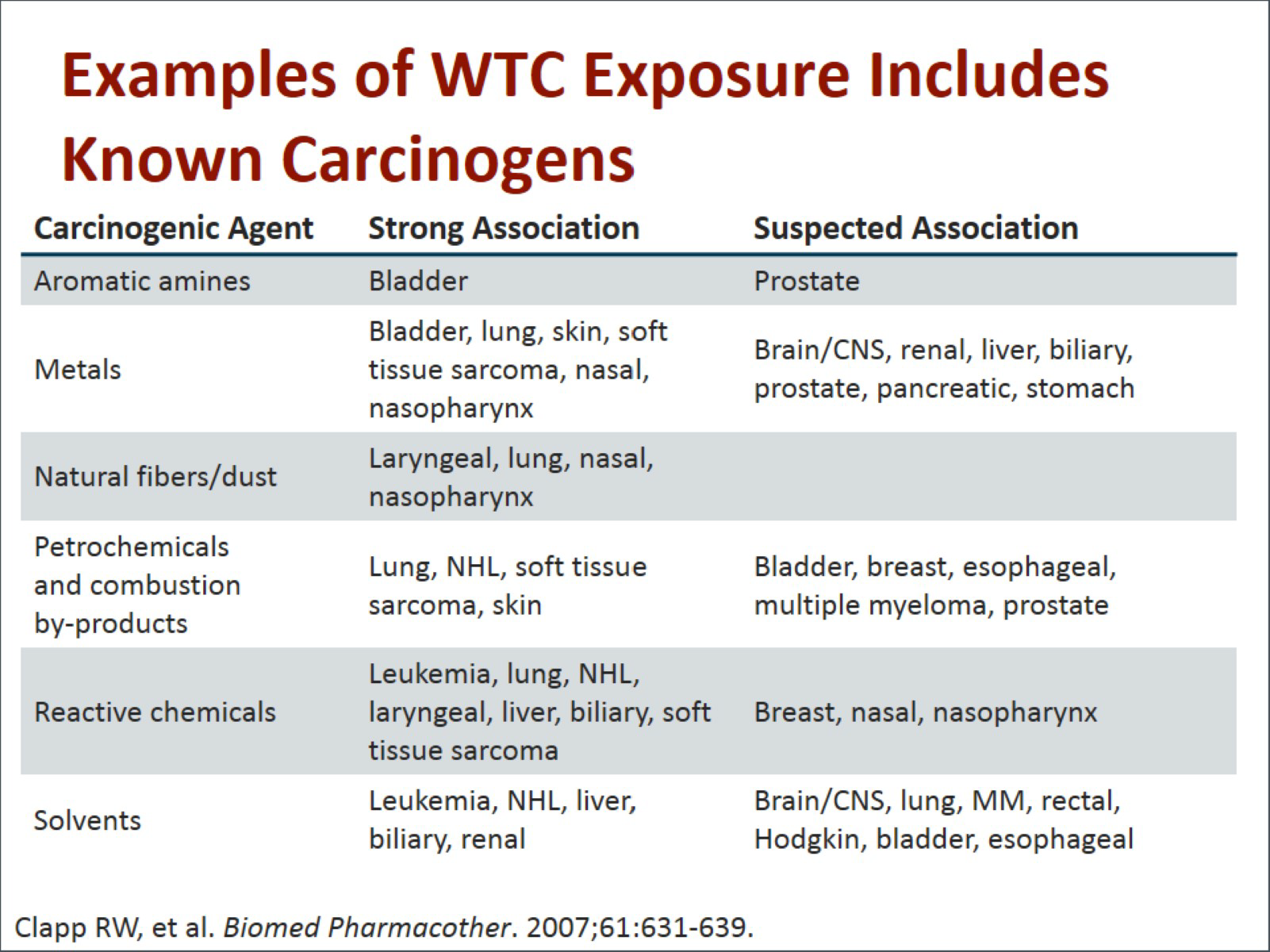

David J. Prezant, MD: When we look at the association between some of those contaminants and cancer, we see a strong association with aromatic amines and bladder cancer, a suspected association with prostate cancer. We know from previous studies that heavy metals all have a strong association with bladder cancer, lung cancer, sarcomas, and upper airway nasal and sinus cancers, and a suspected association with all neurologic, kidney, liver, prostate, pancreas, and stomach cancers.4 There are real associations that have been demonstrated in the literature based on other exposures.

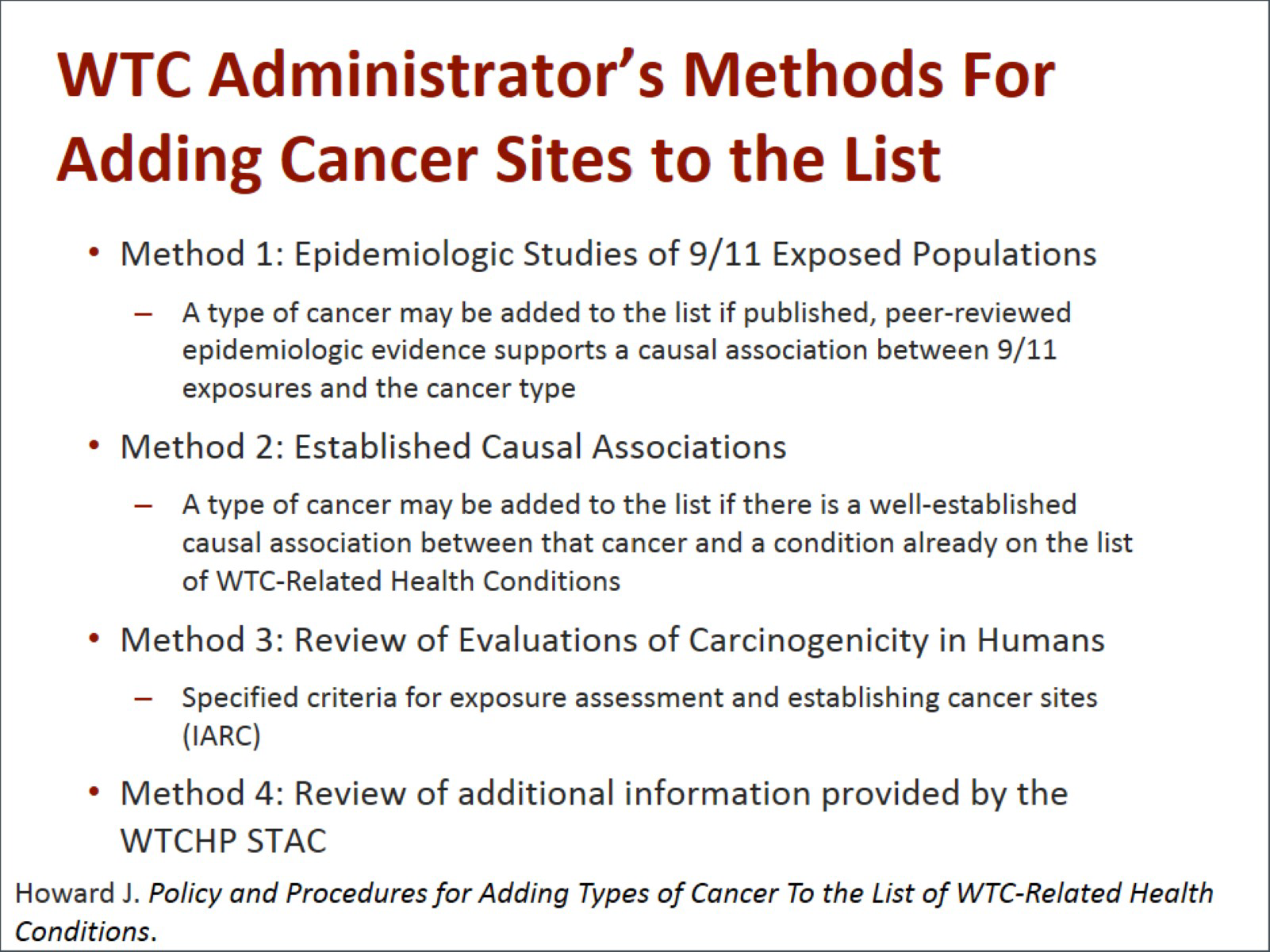

Dr. Ward: The STAC recommended that we figure out which cancers to include by looking at epidemiologic studies in WTC responders and survivors. We also recommended looking at the cancers that had been associated with specific exposures that were present at the WTC by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). A great example of that is asbestos. We know that asbestos was present at the site, so we included those cancers that had been associated with asbestos, based on epidemiologic studies associated with an IARC review. Finally, we recommended including cancers that occurred in sites that were associated with conditions that already had been established as WTC-related.2

Mark Farfel, ScD: I think it is important to mention that the STAC had a very challenging task in considering this because in terms of the epidemiological studies on WTC-exposed populations, the cancer studies were at the very early stages, and there were only a limited number of publications at that point. Other cohorts were looking at their data but had not yet published.

Dr. Ward: I think that is a very important point. We knew even then that it might take 5, 10, 15, 20 years before we could really understand the full extent of any cancers associated with WTC exposures. Therefore, it was even unlikely that at 10 years we would necessarily have a very definitive assessment, and therefore, we had to look at other sources of data in addition to epidemiologic studies. That was an important basis of why we included the IARC carcinogens and associated sites.

We also recommended that as the new epidemiologic studies were completed and published that the results of those be reviewed, and if appropriate, cancers be added to the list. We recommended that since some cancers may be diagnosed through early detection, that the WTCHP provide funding for cancer screening.

Dr. Farfel: I think there is intense public interest in early cancer findings related to 9/11. I know that the WTC Health Registry met with community and labor advisors early on about this.

Dr. Ward: The administrator took the STAC's recommendations under consideration as well as other sources of information, and he established a method by which cancers would be added to the list at that time and in the future. The first method, method 1, was that a cancer may be added to the list if peer-reviewed epidemiologic studies found a causal association between that cancer and exposure to 9/11. We all knew that would probably be a difficult condition to satisfy, but, of course, it is important that it be included. The second method defined by the administrator is that a cancer can be added if there is a well-established causal association between that cancer and a condition already on the list of WTC-related conditions. The WTC also considered a method whereby the criteria for establishing cancer sites from the IARC would be used. So if the IARC review finds an association between benzene and leukemia and lymphoma, then that site could be added, based on that IARC review, as long as benzene was a documented exposure at the WTC. Finally, the administrator allowed for considering any additional information that was provided by the WTCHP STAC.5

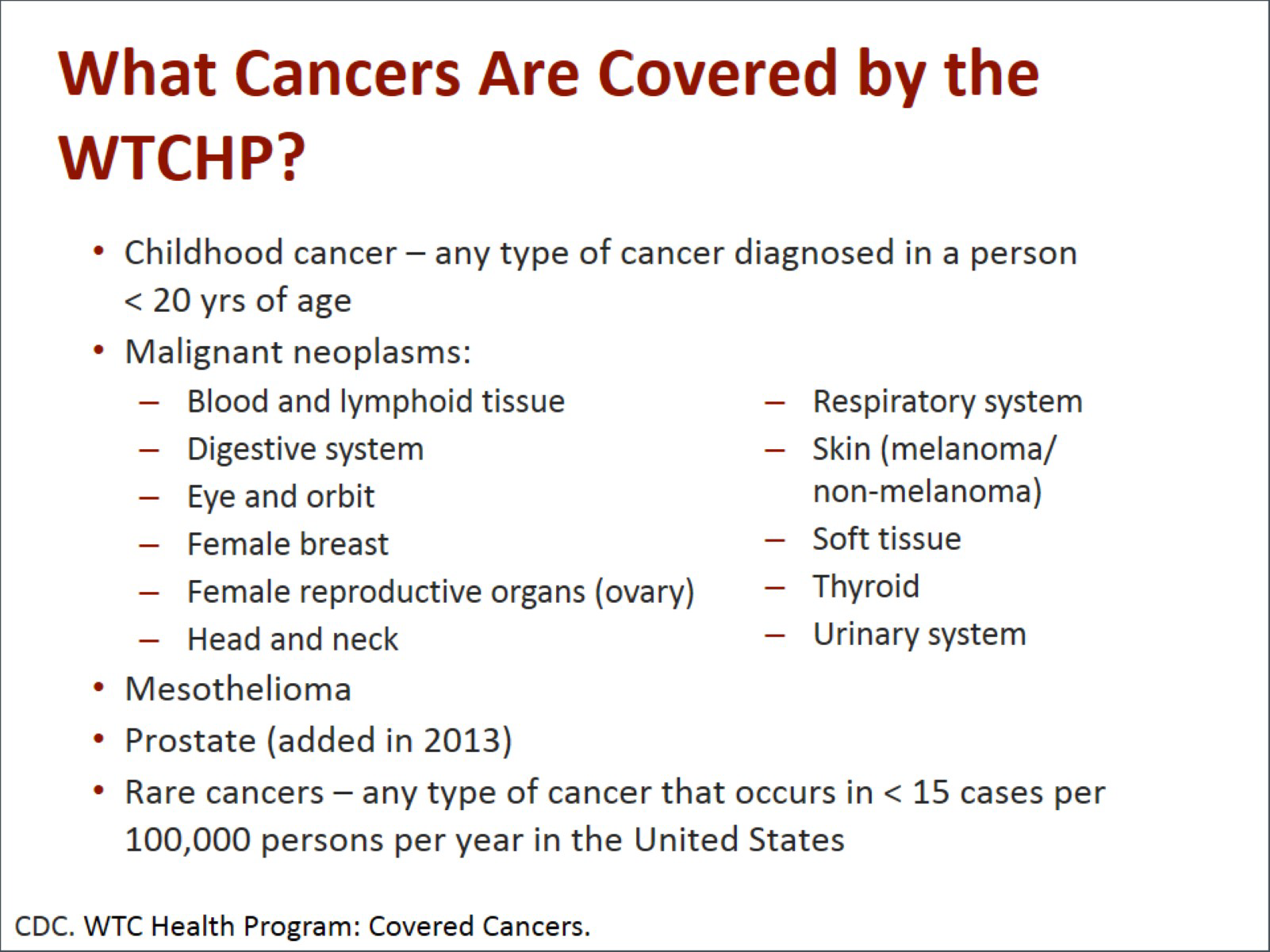

Dr. Prezant: What cancers are actually covered by the WTCHP? Childhood cancers, of course, and other common cancers in adults. Prostate cancer was added in 2013 when new studies came out showing that all 3 groups had demonstrated an increase in prostate cancer and the STAC had the foresight to recommend that rare cancers be covered because epidemiologically we may never have enough of those cases to demonstrate a true association.6

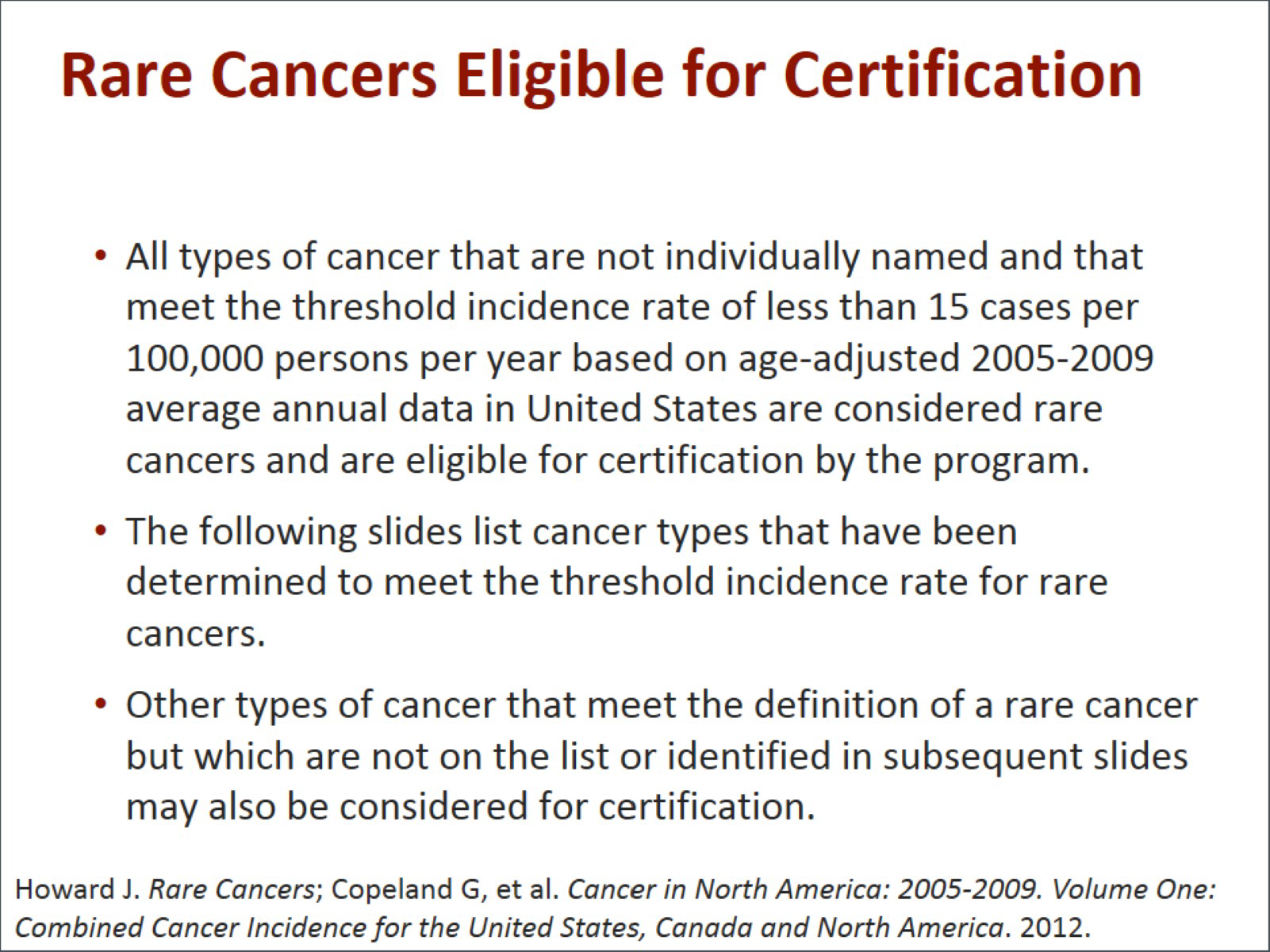

Are there cancers covered that we did not realize at the time? Yes, any cancer not named but that meets the threshold incidence, which is defined as an incidence rate of less than 15 cases per 100,000, is considered a rare cancer, and it is eligible for certification if the administrator so chooses.7,8

There are a number of cancers that would fall into that group, such as very unusual cancers of the adrenal glands, of the lower gastrointestinal canal; breast cancers among men, (which are already covered among women but are very rare among men); gallbladder cancer; brain cancer; pancreatic cancer; thymus cancer; and many others.7

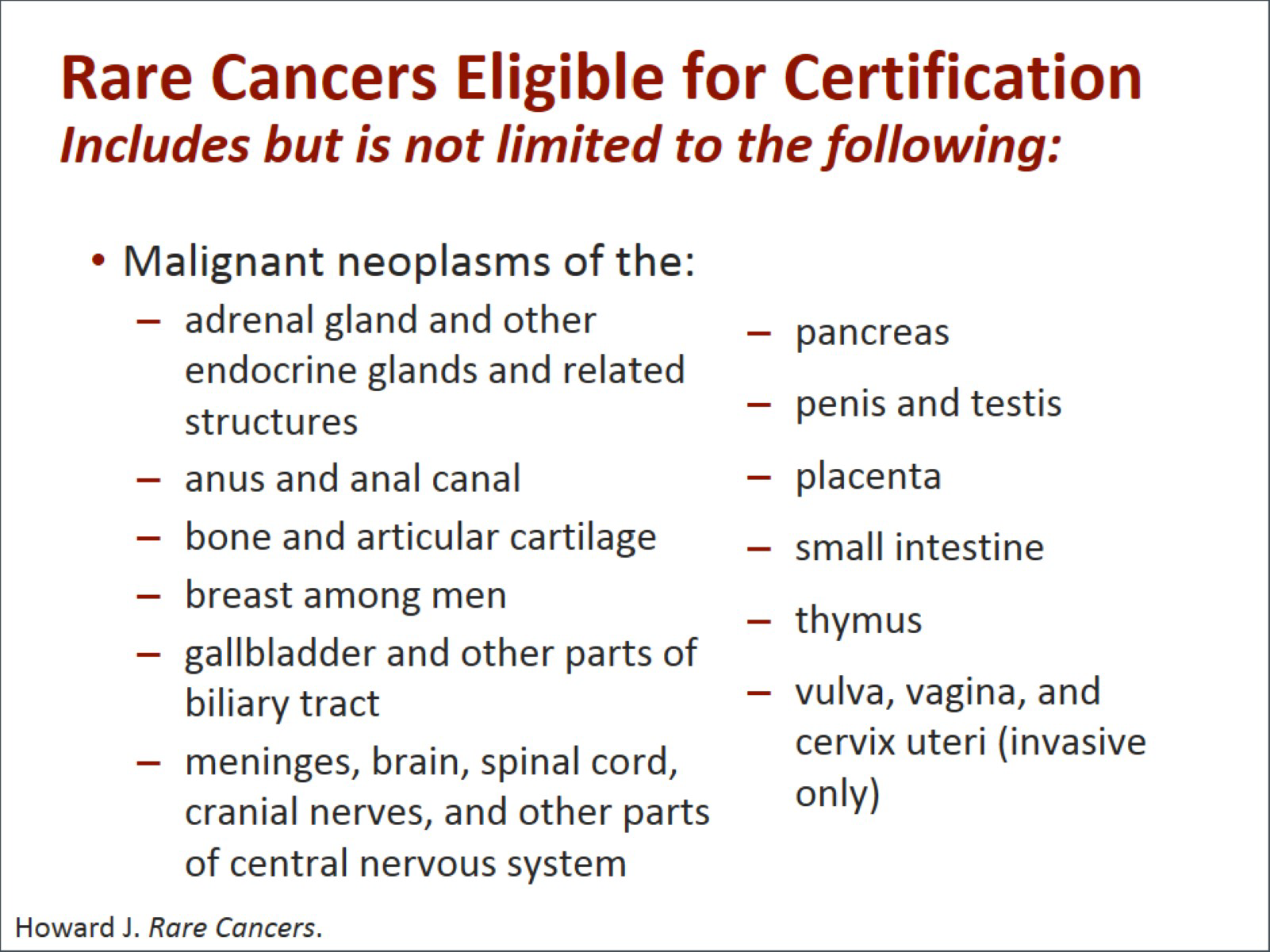

Neuroendocrine cancers, no matter where they appear, they are called neuroendocrine, but they can appear in other organs that are not typically related to the neurologic system. In addition to the hematologic cancers, they added in the myeloid neoplasms, which are precursors for many of these cancers and are now covered, very importantly.7

Dr. Farfel: Given, as I said earlier, the intense public interest and possibility of early cancer effects following 9/11, the cohorts had actually anticipated these analyses and discussed early on how to approach assessment of cancer in the cohorts. Each cohort took an initial look at data through 2008 and published those findings. The first published findings actually came out from your cohort Dave, the fire department, followed by the registry in 2012, and then the WTC Health Consortium in 2013. What is striking about all 3 studies is that there were methodological differences, including recruitment strategies, exposure assessment, the demographics of the population, the handling of latency, and the length of follow-up; yet, despite all of these differences and others I have not mentioned, the studies did arrive at similar conclusions.9-11

I think we are all in agreement that the presence of these 3 cohorts actually strengthens our work to identify and quantify cancer risk related to 9/11 and that these differences in design across the 3 studies may actually elevate the sensitivity of the research for identifying a cancer risk related to 9/11.

Dr. Prezant: I think a hallmark of causality research is to be able to reproduce those findings in other cohorts, and the fact that we have done that is probably the strongest evidence that there is really an association with cancer.

Dr. Farfel: What we are going to do next is to talk a little bit about the details from each of the three early cancer studies.

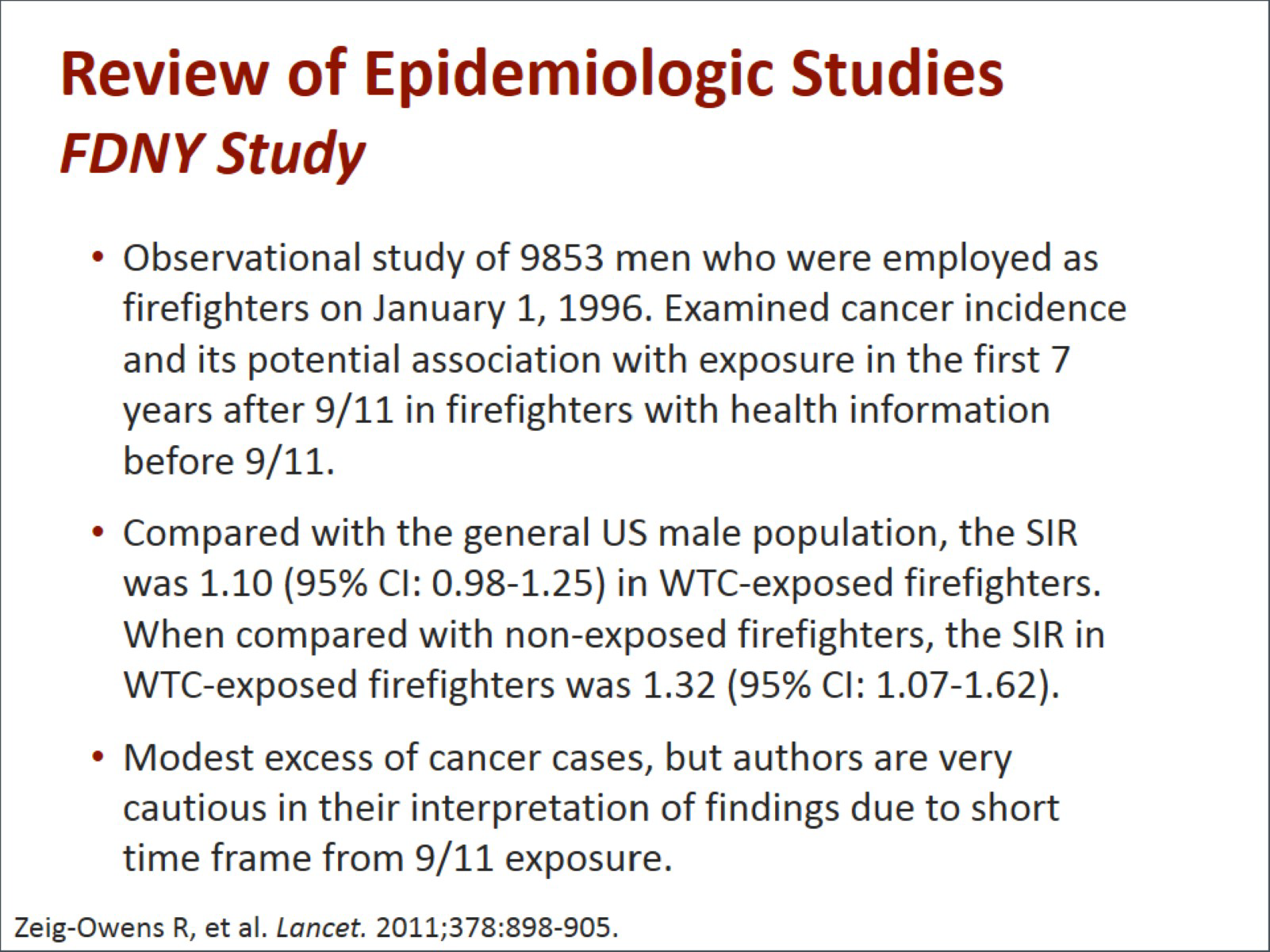

Dr. Prezant: The first study was in New York City firefighters and emergency medical service workers, but we concentrated in this study on the firefighters. It was a study of nearly 10,000 male firefighters who had been employed at the fire department since January 1, 1996. One of the unique aspects of the fire department is they were able to not only look at what has happened since 9/11 but compare it to what happened in the same cohort before 9/11. When we compared the cohort to the general US male population, there was an increased incidence, with a standardized incidence rate (SIR) of about 10% above normal: 1.10, in our WTC-exposed firefighters. When we compared it to our nonexposed firefighters, we saw that the SIR increased anywhere from 19% to as high as 32%, depending on the statistical methodology used. We found a modest excess of cancer cases but a real excess.9 We are cautious in interpreting these findings. We need those long-term studies, especially when it comes to identifying the individual cancer types.

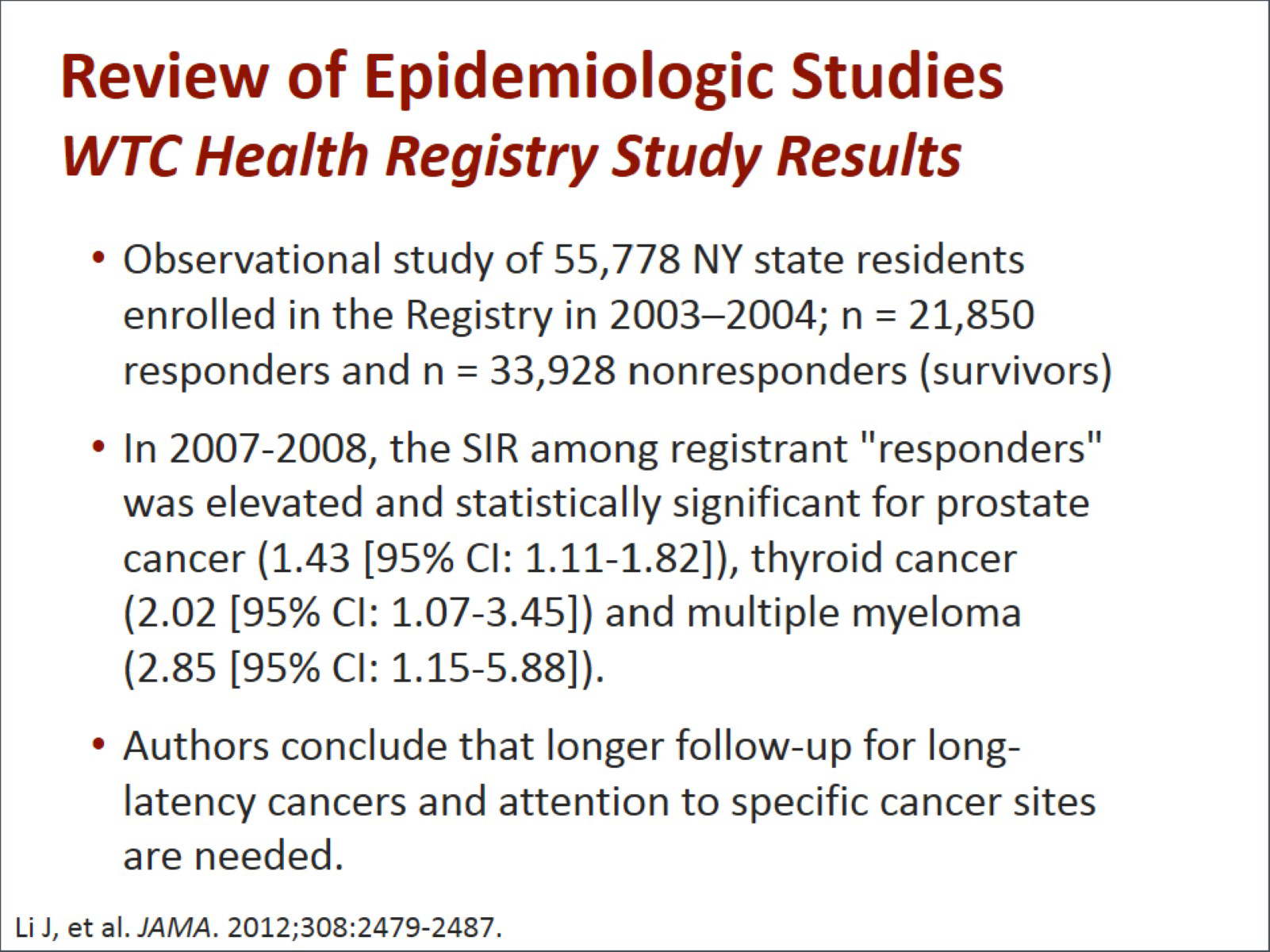

Dr. Farfel: The second study was conducted by the WTC Health Registry, and this was a large observational study. We focused on the New York state residents because most of our enrollees actually lived in New York state at the time of 9/11 and continue to do so. We included in the first look almost 56,000 New York state residents, who were enrolled in the registry in 2003 and 2004. We looked at people who were at risk for first primary cancer at the time of their enrollment in the registry. We also linked our registry to the New York State Cancer Registry, and we also included 10 other state cancer registries. We did that in order to be able to identify cases that occurred among residents of New York who moved out of state, and those 10 state cancer registries covered about 95% of all our enrollees.

The second hallmark of our study was that we chose to focus on the cancers that occurred in 2007 and 2008, because we believe that during that time period, the cancers were more likely to be related to 9/11 exposure than the cancers in the enrollees that may have occurred during the first 5 years after 9/11. Similar to the fire department findings, when we look at this later 2007 and 2008 period, our SIRs among responders in the registry were elevated for prostate cancer and thyroid cancer. We wanted to see if the intensity of the exposure was related to the occurrence of specific cancers. We did not find a statistically significant association; however, when we looked at the hematologic cancers that you spoke of earlier, we did find a trend that was not statistically significant but a trend of increasing risk with increasing 9/11 exposures.10 Like you, Dave, we also came to a conclusion that given the relatively small numbers and the short period of follow-up, we need to be cautious and that we really highlighted the need to do longer-term follow-ups as the key to this analysis.

Dr. Crane: I guess we will be saying this again and again, but this is very early in the stage of a possible cancer development for any occupational exposure. Five to seven to eight years is barely in the door for the beginning of cancer from an occupational exposure, so we will keep on saying that.

The consortium study, which was solely the responders, looked at cancers among almost 21,000 WTC members and found 575 cancers, elevation of incidence ratios in thyroid cancer, prostate cancer, combined hematopoietic and lymphoid cancers, and some soft tissue cancers. Again, interpret these results with caution because of the very short follow-up period. There may also be changes in future populations because with the small numbers we found, they could not be considered predictive of the future, but, in general, they substantiate the elevated risk of cancer for this population and found in the other 2 studies.11

Dr. Ward: This next slide summarizes the results of the three studies side by side: All 3 studies found a modest either statistically significant or nearly statistically significant excess in risk. Another really important point is that for lung cancer, which is one of the most common cancers and one that is often associated with occupational exposures as well as smoking, none of the 3 studies observed an elevated risk.

The other cancers that are listed on this slide are cancers that were in excess in one or more of the studies, and I am struck when I look at it by how consistent it is. Two of the studies showed melanoma. The third study did not show melanoma. All 3 cohorts showed excesses in prostate and thyroid cancers. Now, that is one where many epidemiologists would have a concern that these cancers are appearing in part because of screening and early detection. Of course, we can never be really sure about that because people who are in the WTCHP would be seeing physicians and are more likely to get screened. The other cancers I think are very significant because the hematologic cancers are cancers that are likely to arise with short latency, and so the fact that we are seeing excesses in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma may be a really important signal that we need to look at these carefully in the future.9-12

Dr. Crane: Elizabeth, the fact that we are not seeing elevated lung cancer by now does not mean there is no risk; is that correct?

Dr. Ward: That is correct. Lung cancer is one of the cancers that tends to have a longer latency. We really need to look long-term, and we need to compare the highly exposed to the less highly exposed. The general population may not be a good reference group for these unique healthy worker populations and survivors.

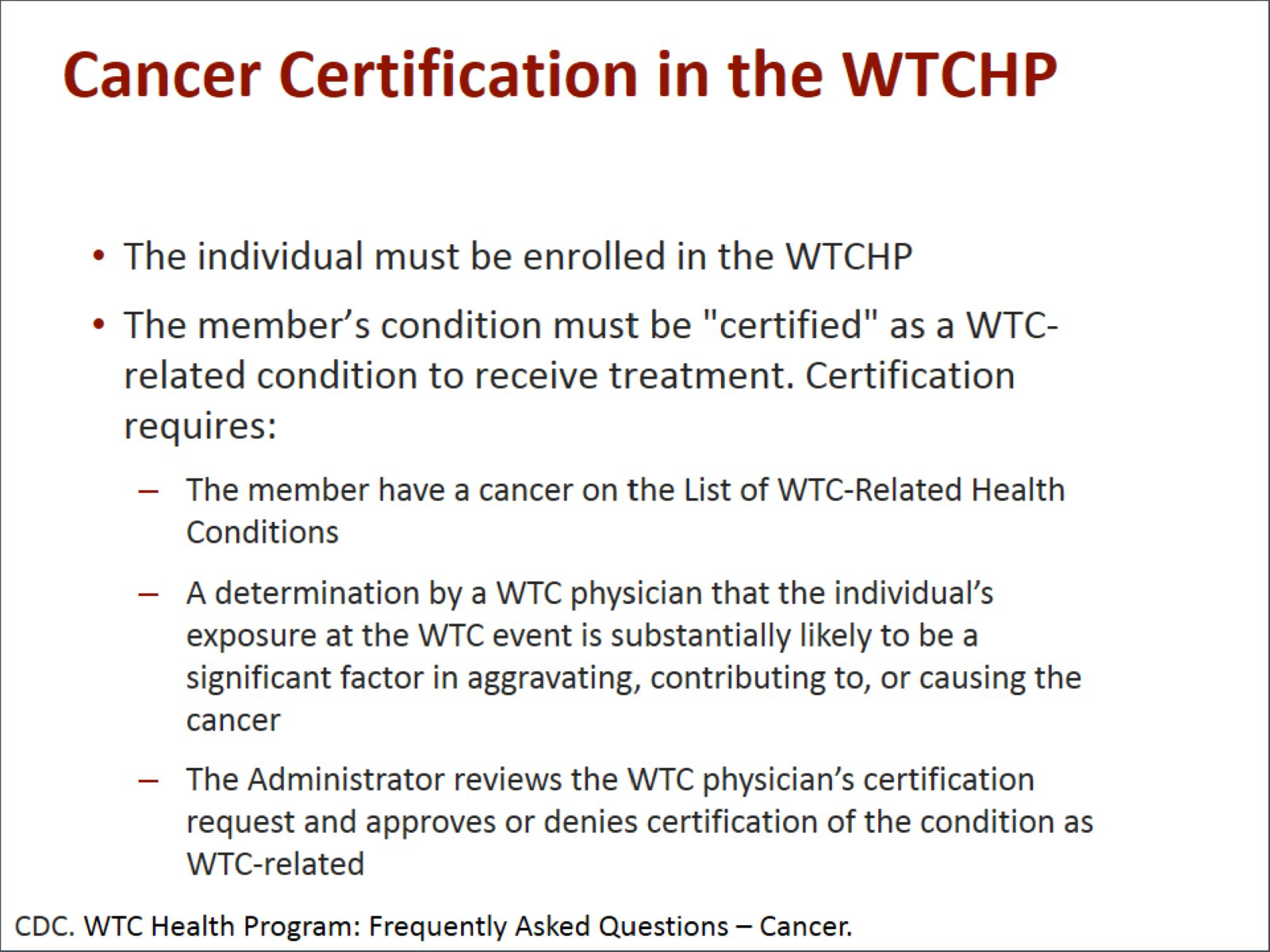

Dr. Crane: We are going to talk a little bit in pragmatic terms now about how folks get covered for cancer and how their cancers get treated in the WTCHP. Among the things that must occur under the Zadroga Act is individuals have to their cancers "certified." To have your cancer certified, you must first be an individual who is enrolled in the WTCHP. The certification requires that the member have a cancer that is on the List of WTC-Related Health Conditions that you have just seen and a determination made by a physician involved with the WTCHP that the individual's exposure was substantially likely to be a significant factor in aggravating an underlying condition or causing that cancer. The administrator then approves the certification that the cancer is in fact a WTC-related cancer. The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) then certifies that cancer as WTC-related.13

Dr. Prezant: I think it is important to note that this is an independent review, so the WTCHP, which typically is not actually treating the cancer, is looking at all the medical evidence both for the exposure and for the disease and has to come to that conclusion of substantially likely. Even then, an additional review is done at the federal government level by physicians who have never seen the patient, who have no relationship with the patient, and likewise feel that this is consistent with the STAC's recommendations and with the federal regulations governing the program. This is a very responsible careful decision because we know the enormity of it. We know that these people now are covered under this program.

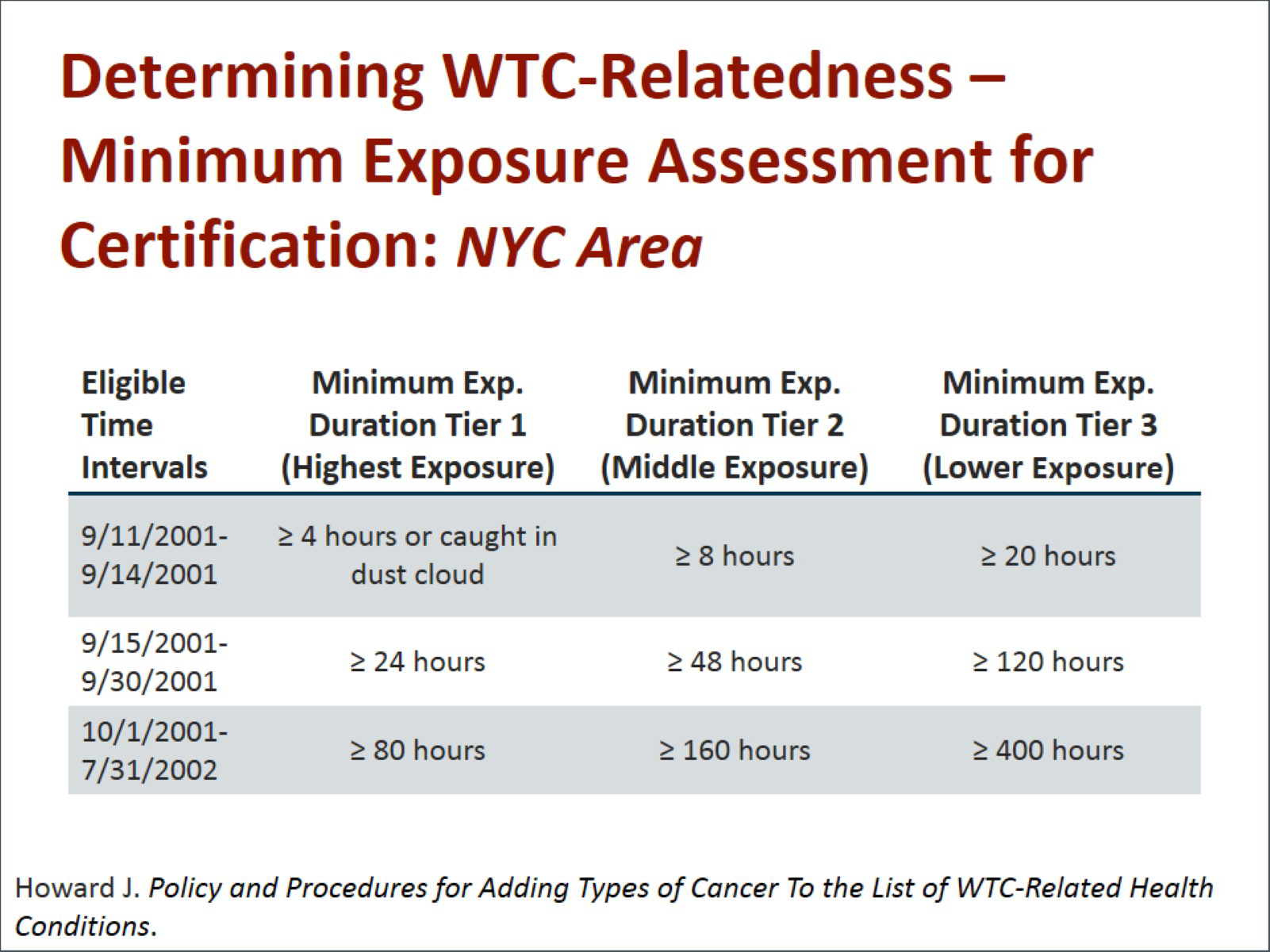

Dr. Crane: What you will see now is a matrix about exposure in cancer coverage. Our exposure assessment depends upon a couple of factors. We had no measurements on site of live coverage of the dust cloud, so our assessment depends in many instances on the time when individual patients arrived on the site, how long they were there (duration of their exposure), and the nature of that exposure, chiefly involving what type of work they were doing or what kind of living condition they had. You can see it depends here if you were there on 9/11, a minimum exposure for an individual to be considered if they had a cancer develop is about 4 hours. If they arrived at later times, when there was less dust in the area and a little bit more controlled conditions, that exposure could be longer, and you will see that in the chart.14

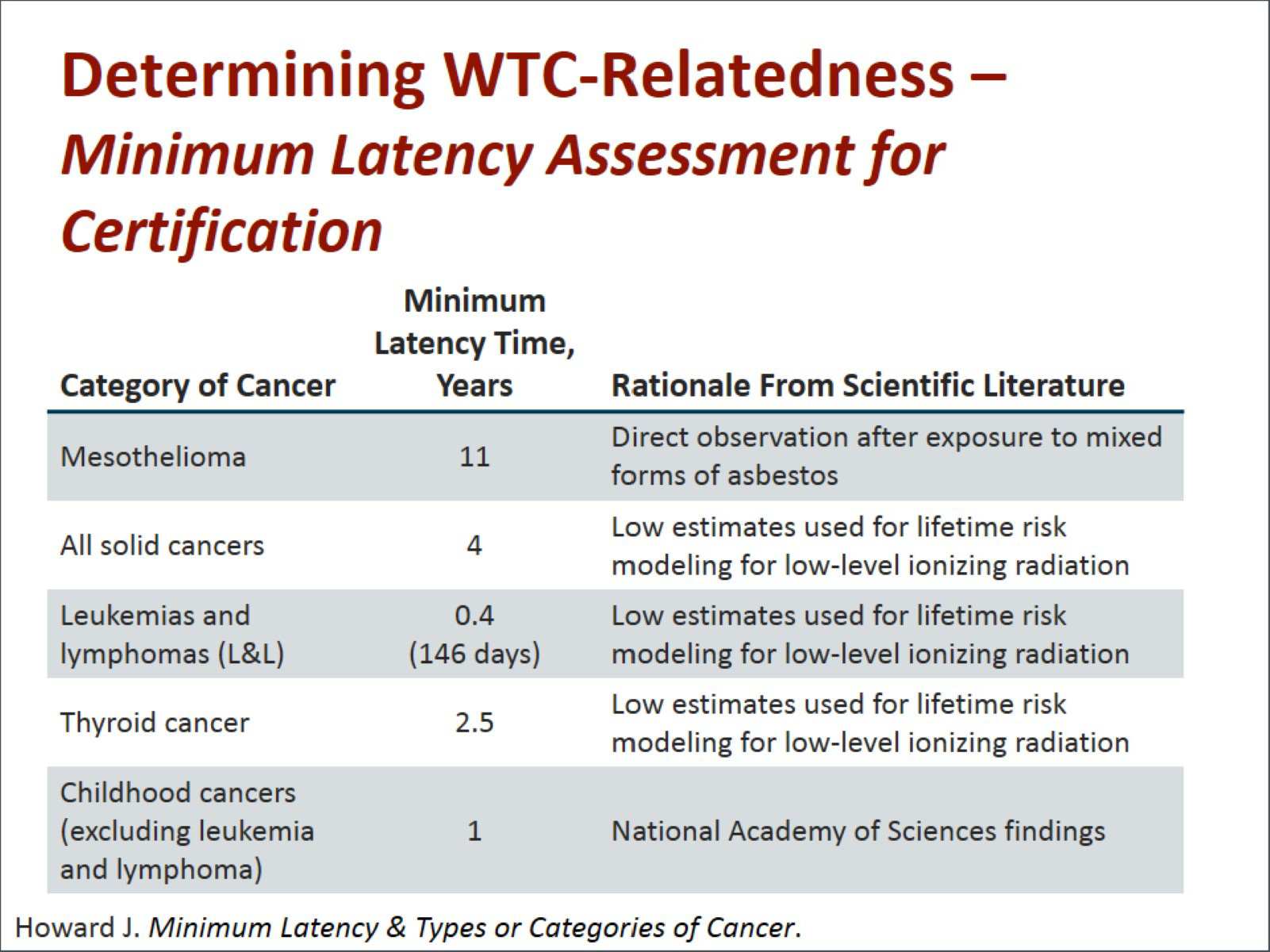

Dr. Ward: In addition to the intensity of exposure, the WTCHP established criteria of minimum latency periods for different types of cancers to be certified. It did this based on what is known from the epidemiologic literature.15 The idea of establishing the minimum latency was to really determine that there was a biologically plausible, scientifically valid association between the exposure at the WTC site and the specific type of cancer.

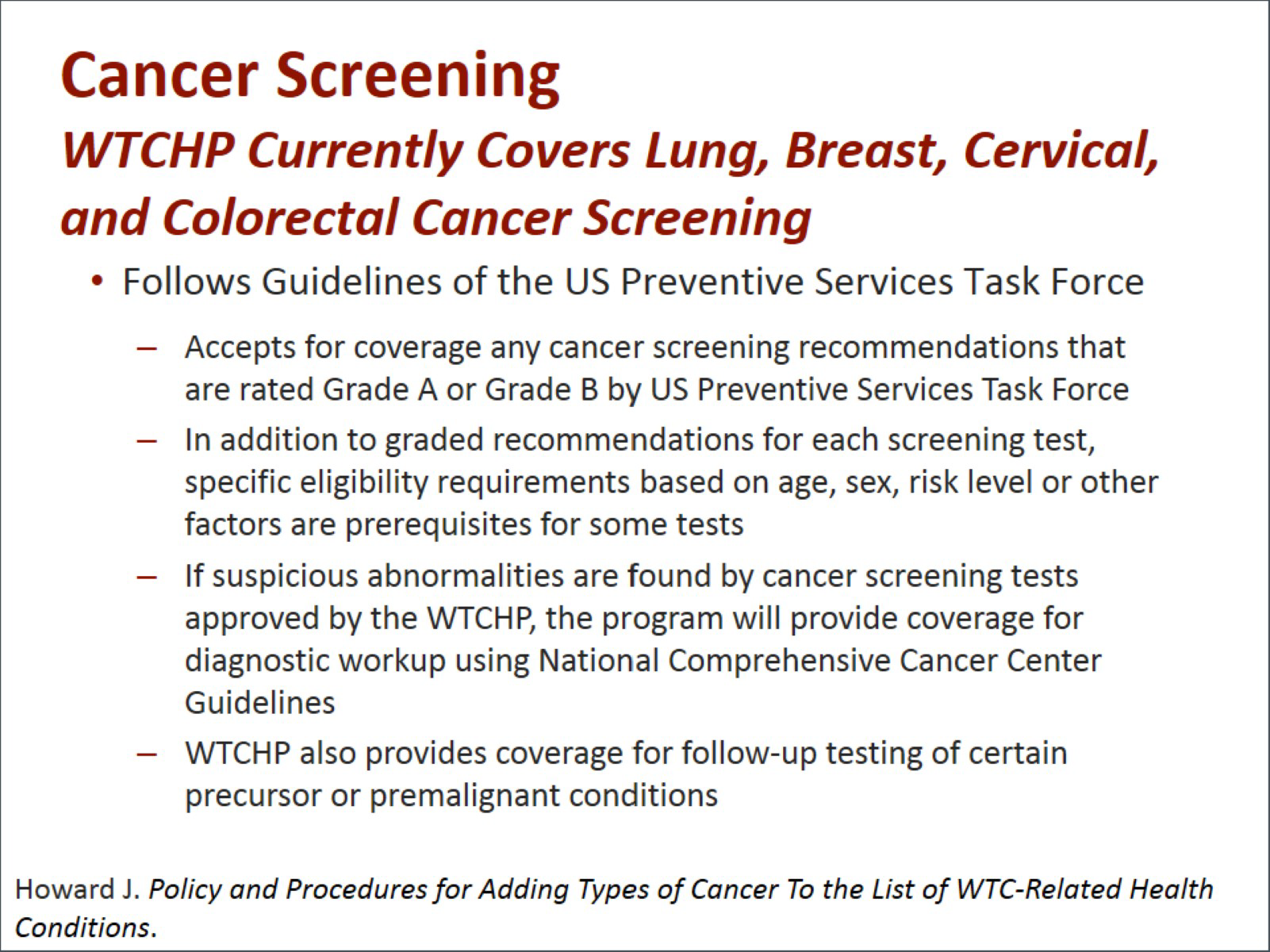

Dr. Prezant: In terms of being proactive, thankfully, this program also covers cancer screening, and we follow the guidelines of the US Preventive Services Task Force. We cover cancer screening for anything that is rated at a grade A or a grade B by this task force. In addition to treating the cancers, we are actually screening for cancers and trying to find early disease when we can best do that.16

Dr. Farfel: The WTC Health Registry was actually designed to track the long-term mental and physical health impacts of 9/11 and also unmet healthcare needs; however, we are the one cohort program that does not provide direct clinical care. Fortunately for us, like the clinical programs, the NIOSH WTCHP has empowered us with tools to reach out and link our enrollees to the WTCHP. We have our enrollees report their health symptoms and conditions to us through their periodic health surveys. We contact those people who report 9/11-related symptoms and try to encourage them to enroll in the WTCHP so that we can meet unmet needs.17

Dr. Ward: I would like to summarize the key messages and lessons learned from this presentation. The first one is that based on the presence of carcinogens, some responders and survivors may develop cancer from their experiences. We do not know how large the risk is. We do not know for sure what cancers will be affected. It is quite possible that most people who were exposed to the WTC dust will not develop cancer as a result of their exposure, but as you have heard today, there are good studies in place so that we can identify those increased risks if and when they occur. We also have programs in place to help people in terms of identifying the cancers early, possibly detecting some cancers, and getting treatment. Because many cancers have long latency periods, we have emphasized throughout this program that it is extraordinarily important that people who are enrolled in the WTCHP continue to be monitored and offered screening and early detection and that research continue. In addition, even if a person is not currently a member of the WTCHP, they can apply to the program to be certified as a cohort member and be eligible to receive cancer screening. That is a very important benefit that I suspect many people may not be aware of, and, finally, I think it is important for everyone treating patients who may have cancers related to their WTC exposure to understand that approved cancer treatment is covered by the WTCHP if the person's cancer is deemed eligible by the administrator. That person can receive treatment where they want to receive treatment as authorized by a WTC physician. The WTCHP is collaborating with many highly qualified oncologists and health centers, so the treatment that a person receives will be top-notch.

Dr. Prezant: I think you bring up an important point to the listening audience that this is not just a New York City problem. In every state of the nation, in almost every congressional district, there are people living right now who have been exposed to the WTC in any of the ways that we have previously described. An oncologist, a primary care doctor, or a gynecologist may see those patients and may forget to ask, "Were you exposed to the WTC?" because they do not live in New York state. Every time we diagnose somebody with cancer in this country, we should know what their occupational and environmental exposures were, and we should add to our question list, "Were you exposed to the WTC?" because that opens up a whole potential for us better understanding the disease, as well as offering treatment to that individual.

Dr. Crane: These are some resources available for finding out more about the WTCHP. Finally, there is more information about the WTC Health Registry at their website.17-19

Dr. Farfel: Thank you. You can find summaries of all of the registry's research on physical and mental health outcomes on the website, including brief videos with the authors of our papers reporting on findings and enrollee testimonials to give you an idea of what is on their minds as well.

Dr. Ward: I would like to thank you for participating in this very informative and interesting discussion today.

Dr. Prezant: Thank you.

Dr. Farfel: Thank you. I enjoyed the opportunity.

Dr. Ward: Thank you to our viewing audience for participating in this activity. Click on the Earn CME/CE Credit link to take the CME/CE posttest. Thank you again.

This transcript has been edited for style and clarity.

Practice Assessment

How will you improve your practice? Please click on the "Continue" button to assess your planned changes in comparison with your peers by completing this brief survey. (Note: the following questions were developed by an independent consulting group with expertise in assessing the effectiveness of medical education.)

File Formats Help:

File Formats Help: