AMD Projects: Learning from Listeria

Maximizing the potential of real-time whole genome sequence-based Listeria surveillance to solve outbreaks and improve food safety

2017 Project Completion

This project helped CDC improve foodborne pathogen identification and characterization. Since 2013, many Listeria outbreaks have been detected, investigated, and solved using WGS. This included solving small outbreaks and outbreaks with cases that span over a 5 year period that likely would not have been detected using PFGE alone. Ultimately, we’re identifying food sources and stopping outbreaks of Listeria sooner, so fewer people get sick.

WGS proved so successful at detecting and solving outbreaks and linking illnesses to food sources that CDC is upgrading all foodborne disease identification activities to WGS. After implementing WGS for Listeria, CDC expanded its WGS capacity for other foodborne pathogens, including Campylobacter and E. coli in 2014, Salmonella in 2015, Vibrio and Shigella in 2016, and Yersinia and Cronobacter to come in 2017. The Listeria project is helping build the PulseNet foodborne tracking databases of foodborne bacteria into a fully WGS-based system. In addition, by the end of 2017, public health laboratories in all 50 states will have PulseNet WGS sequencing capacity. It is expected that PulseNet will function entirely on WGS by the end of 2018.

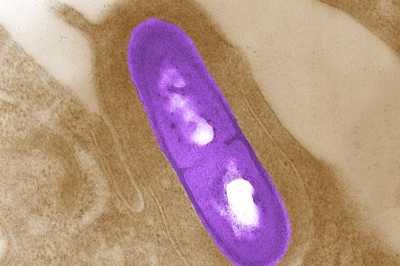

Listeria, a rare but deadly germ, is the 3rd leading cause of death from food poisoning.

Many germs can be spread through food. Some, like Listeria can be deadly. Listeria is the third leading cause of death from food poisoning. Most people found to have Listeria infection require hospital care. About 1 in 5 people with the infection die—it strikes hard at pregnant women and their newborns, people 65 or older, and people with weakened immune systems.

And if Listeria illnesses occur far apart, current methods cause health officials to lose time figuring out which illnesses are part of an outbreak.

For decades, scientists have tested Listeria germs using a technique called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, or PFGE, to find which infections are related and part of an outbreak. But with PFGE, unrelated Listeria germs can sometimes look similar and closely related ones can look different. In comparison, whole genome sequencing determines an organism’s complete genetic composition with greater clarity. This technology also replaces several steps of laboratory work with a single, fast method and allows for detailed comparison of Listeria germs submitted from diverse sources.

In September 2013, scientists at CDC, NIH, USDA, and FDA—along with state public health departments—began comparing PFGE with whole genome sequencing. This partnership is the key to connecting clues about human illness, contaminated foods and environmental hazards—and making that information available to others.

This project will apply lessons from Listeria to further transform outbreak detection and response for other priority foodborne infections, such as E.coli and Salmonella. These new techniques enable CDC to give partners the information they need to be more confident in their food safety decisions, whether it is through regulatory action and enforcement, recalls, changes in manufacturing and processing, or more precise consumer messaging during outbreaks.

- Page last reviewed: April 24, 2017

- Page last updated: April 24, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir