Chikungunya Nowcast for the Americas

Questions and Answers

What are public health models used for?

In recent years, infectious disease modeling has been increasingly used to help public health experts identify and understand factors that influence when and where outbreaks occur and to what extent they may spread. By helping us identify factors that influence introduction of viruses to specific geographic locations we can better design methods to prevent virus transmission.

What does this nowcast model predict?

This monthly nowcast was developed to help CDC scientists estimate:

- Where travelers infected with chikungunya virus are likely to arrive;

- And, which locations are at risk of having new local transmission of chikungunya virus.

Why doesn’t the nowcast predict spread of the virus into the future?

CDC developed the model to provide information on the continuously moving front of the epidemic rather than to predict spread of the virus into the future. Predictions into the future would require a different type of model.

How should estimates from the chikungunya nowcast be used?

The nowcast model estimates helps to identify when and where chikungunya spread is likely. This information can be used for planning and timing outreach programs to the public, media, and to health care providers. These activities can raise awareness in the public and medical community, which can lead to early recognition of cases or potential outbreaks in the area. Key education and outreach should focus on:

- Raising awareness of chikungunya in the community;

- Recognizing the signs and symptoms of chikungunya;

- Encouraging the public to seek medical care if/when sick;

- Educating the public about how to protect themselves from chikungunya;

- Planning and implementing disease surveillance activities; and

- Planning and implementing mosquito control activities.

This nowcast model does not estimate:

- Spread of chikungunya virus from other areas outside of the Americas.

- Spread of other mosquito-borne infectious diseases like dengue or West Nile virus.

- How many chikungunya cases may occur in an area.

- Spread of chikungunya virus by travelers not traveling by airplane.

- How local public health interventions (e.g. mosquito control, personal protection measures) might impact the outbreak.

The nowcast predicts local transmission of chikungunya in my area, but there are no reported cases of chikungunya. Why is there a discrepancy?

The nowcast model predictions are based on probability, not certainty of an event.

There are two main reasons that help to further explain the discrepancy:

- The nowcast estimates are generated by a mathematical model incorporating the number of reported chikungunya cases, historical airline flight, local climate data and estimates of:

- How often an infectious mosquito feeds;

- The probability of human-to-mosquito transmission;

- How long a mosquito survives;

- The probability of mosquito-to-human transmission of the virus.

- Not all cases of chikungunya are recognized or reported

There are important limitations to recognition and reporting of chikungunya.

- Some people infected with chikungunya virus don’t get sick.

- Not everyone sick with chikungunya virus goes to the doctor.

- Since it is a relatively new disease in the Americas, doctors may not correctly recognize it.

- If the doctor recognizes that the case may be chikungunya (it can be confused with other diseases), they may report the case and order testing.

- Chikungunya is not a nationally reportable disease in the United States (reporting will become mandatory in 2015). However, reporting by doctors is encouraged.

How accurate is the nowcast model?

The model predicted the likely introduction of chikungunya virus transmission to most locations either before or at the time when the first cases were reported. Out of the 10 locations with the highest probability of having cases after St. Martin, nine had reported cases by the end of April.

Is this chikungunya epidemic going to continue spreading throughout the Americas?

Yes. Since December 2013, the chikungunya virus has spread to many new countries and territories in the Americas (the Caribbean, Central, Latin, North and South America) and infected increasing numbers of people.

As long as the chikungunya epidemic continues, travelers may become infected and spread the virus. The mosquitoes that can transmit chikungunya virus are common in many parts of the Americas, including parts of the United States. In these locations, travelers infected with chikungunya virus may be bitten by mosquitoes after returning home, which can lead to local cases or outbreaks.

- Click here for information on countries where chikungunya has been found.

- Click here to see the latest number of cases in the United States.

Should we be concerned about chikungunya virus in the United States?

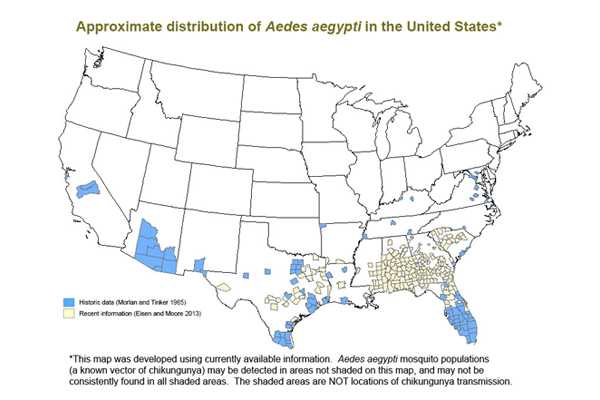

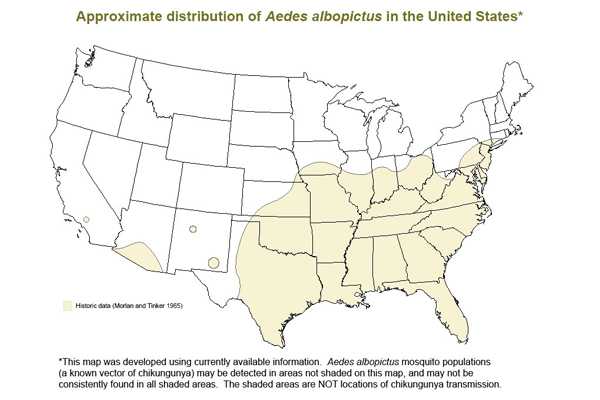

Yes. Each year, millions of travelers visit countries where chikungunya outbreaks are ongoing. People become infected through mosquito bites. The two types of mosquitoes that can spread chikungunya virus – Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus – are found in parts of the U.S. [PDF – 292 KB] so it is possible for the virus to spread here once imported.

Infected travelers bring chikungunya virus into the U.S. every year. From 2006‒2013, an average of 28 people per year had confirmed cases of chikungunya. All were travelers visiting or returning to the United States from affected areas, mostly in Asia. None of those imported cases resulted in locally-acquired cases or an outbreak.

However, more chikungunya-infected travelers will come into the U.S. from the Americas, increasing the likelihood that limited local chikungunya virus transmission could occur. Since the Caribbean outbreak began in December, 2013, over 750 travelers have returned to the U.S. infected with chikungunya virus. And as of August 2013, a handful of locally acquired cases had been reported in the continental U.S. It is important for public health experts and healthcare providers to be aware of chikungunya in patients with a recent travel history and to test for and report cases.

- Click here [PDF – 292 KB] to see where Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus are found in the U.S.

- Click here for information on chikungunya in the United States.

Are there things that I and my community can do to prevent local transmission or an outbreak of chikungunya?

Yes. There are a variety of things you can do to protect yourself and your community from chikungunya. Because there is no vaccine to prevent or medicine to treat the infection, follow these guidelines to protect yourself from infection with chikungunya virus and other mosquito-borne diseases, like West Nile virus:

-

Prevent mosquito bites: cover up and wear insect repellent

The mosquitoes that spread chikungunya virus are aggressive day-time biters. This means you need to protect yourself from bites anytime you are outside during the daytime hours if you are in an area where chikungunya virus has been found.

Cover exposed skin by wearing long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and hats.

- Use an appropriate insect repellent as directed.

- Higher percentages of active ingredient provide longer protection. CDC recommends products with the following active ingredients:

- DEET (Products containing DEET include Off!, Cutter, Sawyer, and Ultrathon)

- Picaridin (also known as KBR 3023, Bayrepel, and icaridin products containing picaridin include Cutter Advanced, Skin So Soft Bug Guard Plus, and Autan [outside the US])

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or PMD (Products containing OLE include Repel and Off! Botanicals)

- IR3535 (Products containing IR3535 include Skin So Soft Bug Guard Plus Expedition and SkinSmart)

- Click here for free downloadable public health prevention posters

-

If you are sick [PDF – 693 KB], protect yourself and others from mosquito bites during the first week of illness.

- During the first week of illness, virus can be found in your blood.

- The virus can be passed from an infected person to a mosquito if the mosquito bites the person during the first week when they are infectious.

- An infected mosquito can then transmit the virus to other people.

-

Support your local and state public health department’s mosquito control activities.

In the United States, mosquito control activities are funded at the local and state level. During an outbreak, aggressive mosquito management can help reduce the likelihood of further spread of the virus.

- Click here [PDF – 292 KB] for more information on mosquito control.

Key Definitions

Imported or Travel associated case

A person who has recently traveled to a country or region with cases of chikungunya who gets bitten by an infected mosquito while traveling and gets sick after returning to the U.S. Click here to view graphic [PDF – 470 KB].

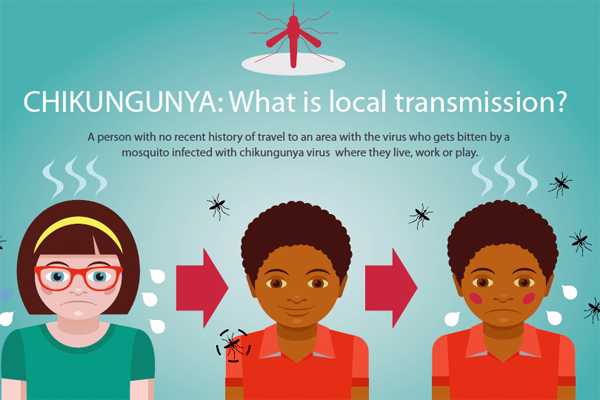

Locally-acquired chikungunya case

A person with no recent history of travel to an area with the virus who gets bitten by a mosquito infected with chikungunya virus where they live, work or play. Click here to view graphic [PDF – 470 KB].

Nowcast

Combination of “now” and “forecast.” A nowcast is an estimation of the present conditions and how those conditions are changing.

Related Links

- Nowcasting the Spread of Chikungunya Virus in the Americas Johansson MA, Powers AM, Pesik N, Cohen NJ, Staples JE (2014). PLoS ONE 9(8): e104915. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104915

- Pan American Health Organization, Chikungunya

- Page last reviewed: August 3, 2015

- Page last updated: August 3, 2015

- Content Source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir