CDC Scientists Working to Protect U.S. Servicemen and Women from Malaria

MCWA was established to control malaria around military training bases in the southern United States and its territories, where malaria was still a problem. Many of the military bases were established in areas where mosquitoes that transmit were abundant. MCWA was created to prevent reintroduction of malaria into the civilian population by mosquitoes that would have fed on malaria-infected soldiers, in training or returning from endemic areas. During these activities, MCWA also trained state and local health department officials in malaria control techniques and strategies.

Long before CDC, and even before its predecessor the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA) was created 75 years ago, malaria control public health workers used nontraditional methods including dynamite to remove tree stumps in order to dig drainage ditches. Drainage ditches helped remove standing water where the larvae of malaria vectors, such as Anopheles mosquitoes, could be found.

World Malaria Day is a powerful and important catalyst that focuses attention on often overlooked work to erase this terrible disease and save millions of lives.

But for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), especially CDC’s Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, the day carries extra meaning since it provides CDC a chance to return to its roots.

CDC’s predecessor, the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA), after all, was created in 1942 with one specific mission—fight malaria and protect members of the U.S. military from the disease wherever they serve. Only four years later, in 1946, CDC was created. And while the mission has dramatically expanded since then, the effort to defeat malaria has remained a major focus and a high priority for CDC ever since.

Not surprisingly, so has the duty to protect members of the U.S. military and the public at large.

Just as they did then, CDC experts are working closely with military scientists to reduce the threat of malaria—for soldiers and civilians alike.

There is a robust portfolio of work, but some of the best examples are CDC and U.S. Navy collaborations to protect sailors stationed—or even temporarily serving or passing through—areas where malaria is a threat.

A Better and Safer Uniform that Saves Lives and Dollars

One proven and successful way to protect people from mosquitoes carrying malaria is to have them wear clothing treated with insecticides.

CDC research chemist Michael Green and U.S. Navy Entomologist LT Michael Kavanaugh have played central roles in developing a simple test that uses a color-coded scale to quickly indicate the amount of insecticide coating on pre-treated military uniforms.

Under the process they developed, a small section of wetted fabric is blotted with a filter that is smaller than a dime and that is then exposed to a chemical reagent. Once the reagent is applied, a color develops on the filter to confirm the presence of the insecticide; the intensity of the color is proportional to the concentration of the insecticide on the uniform. The intensity can then be measured using smartphone image analysis mobile apps. This application will be valuable in helping determine when ineffective uniforms need to be replaced. In addition to maintaining a life-saving defense against malaria, it also will save money, since new uniforms will be supplied only when needed.

A House that Only a Mosquito Can Hate

Another CDC collaboration with the Navy focuses on assessing the shelf-life of building materials coated with insecticides that can help protect servicemen and women living in areas at high risk for malaria.

In this case, CDC scientists and Navy entomologists are evaluating the effectiveness of a novel, long-lasting insecticide used to coat cement, wood, sheet metal, and other building materials, including mud and dung (common building materials used in countries where malaria risk is high).

To determine how well the new insecticide works (or doesn’t), the team uses 12-inch squares of the various building materials, which are then retrofitted in experimental huts located at a Navy training center in Florida.

The treated panels are left to “weather” in conditions simulating those found in Africa to evaluate the insecticide’s residual properties (i.e., how effective it continues to be in killing mosquitoes). A subset of treated panels is shipped to CDC at pre-determined intervals (one week, one month, two months, etc.) to evaluate whether the insecticide still works according to World Health Organization standards and practices.

During each analysis, malaria-transmitting mosquitoes in the CDC laboratory are exposed to the treated surfaces and the death rate is tracked at set time intervals. To date, the analyses show significant mosquito mortality through up to five months of testing.

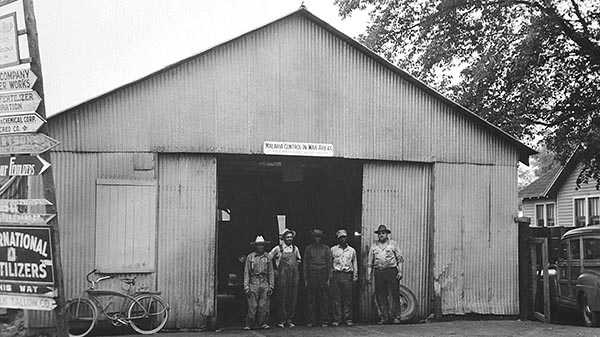

MCWA building in Newton, GA, sometime between 1942 and 1945. Photo from PHIL

These innovative, joint efforts leveraging the respective strengths of both institutions illustrate only a small sliver of the work CDC and the U.S. Navy are doing to combat the deadly malaria parasite, and lessen the terrible toll it takes worldwide. Over the past 10 years, several U.S. Navy entomologists have been seconded to DPDM to work on similar projects and to provide vector control expertise for focus countries of the President’s Malaria Initiative, which is led by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and implemented together with CDC. The entomologists included:

- LCDR Craig Stoops: Malawi

- CDR Dan Szumlas: Ghana

- CAPT David Hoel: Uganda

- CDR Peter Obenauer: Nigeria, Liberia, Rwanda

And while impressive gains have been made globally in reducing malaria’s impact and saving 6.8 million lives in the last 15 years, there is still more work to be done to defeat this microscopic enemy, whether the beneficiaries are military personnel or children in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond.

- Page last reviewed: April 25, 2017

- Page last updated: April 25, 2017

- Content source:

Global Health

Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir