Stories From the Field

These stories illustrate the work CDC and its partners do to advance public health across the United States and around the globe.

CDC experts work with states, countries, and other partners to detect and respond to outbreaks, train professionals and strengthen health systems, and create programs that increase the safety of people’s food, water, and environment.

In the United States

Prompt action by CDC and its public health partners in early 2017 helped stop a fast-moving foodborne outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 (STEC O157:H7) infections.

States use PulseNet to identify and solve outbreaks of E. coli, Salmonella, Listeria, and Campylobacter, and other foodborne infections. In many cases, investigations lead to product recalls. As PulseNet celebrates its 20th anniversary, learn more about how this national laboratory network managed by CDC has helped protect the public’s health.

CDC is upgrading to a single, fast, and efficient whole genome sequencing process. This project will provide more reliable information about the germs that cause most illnesses associated with food, helping increase food safety in the United States and globally.

The use of rapid tests to diagnose foodborne illness pose challenges to monitoring illnesses and progress toward preventing foodborne diseases. FoodCORE centers are making changes so they can continue to identify and investigate foodborne disease outbreaks efficiently.

It is difficult to detect Campylobacter in raw milk, so Utah health agencies collaborated with partners to use a new sampling method to test raw milk for the outbreak strain. Their determination to confirm the source of the outbreak and success of this sampling methods stopped the outbreak and prevented additional illnesses.

Botulism paralyzes or kills quickly. Just one case is a public health emergency, because it can signal an outbreak. That’s why CDC’s botulism clinical consultation service is on call 24/7.

Strong collaboration was key for the Colorado and Tennessee FoodCORE centers when investigating a Salmonella outbreak at a summer camp in Colorado. Teamwork is an important piece of the FoodCORE program. FoodCORE centers collaborate internally between laboratorians, epidemiologists, and environmental health specialists as well as externally with other centers and health departments.

Seven people died and 34 were hospitalized during a multistate listeriosis outbreak in fall 2014. Investigators needed to know which cases of listeriosis were related to find the source of the outbreak. Whole genome sequencing, a laboratory technology that allows for detailed comparison of germs, helped investigators find the source of the outbreak sooner than if they only used traditional lab technologies.

Local health departments detect many foodborne outbreaks through illness complaint systems. The public, however, may not use these systems or may not be aware of them. Staff at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene worked with Columbia University and Yelp, an online review site, to pilot a project to identify foodborne outbreaks that may go undetected through traditional complaint systems.

California scientists and veterinarians found themselves in the middle of a mystery. Over the span of a year, 11 dead or dying sea otters had been found around Monterey Bay, California. The sea otters’ gums had turned yellow and they had swollen livers, but when scientists and veterinarians tested for common diseases that can affect the liver, they didn’t find anything. They started exploring other possibilities and finally found a clue—a positive lab test revealed that the sea otters had died of something called microcystin. Microcystin is a toxin given off by a type of phytoplankton called cyanobacteria, also commonly known as “blue-green algae.”

Candida auris (C. auris) is a multidrug-resistant fungus that can cause serious infections and even death. CDC alerted U.S. healthcare facilities to the risk that C.auris could spread between patients in hospitals, and continues to work with partners to better contain and prevent its spread.

People who get Valley fever are often misdiagnosed with bacterial pneumonia and given antibiotics. However, Valley fever is caused by a fungus, so antibiotics will not work. CDC is working to help healthcare providers better diagnose Valley fever, in part by supporting development of rapid diagnostic tests that can quickly provide clinicians with the information they need to appropriately treat patients.

In the past, scientists believed that Coccidioides, the fungus that causes valley fever, only lived in the Southwestern United States and parts of Latin America. However, cases of valley fever have recently been found in people in the south-central region of Washington State. CDC has been developing new tools that make it faster and easier to detect Coccidioides in the environment.

After an unprecedented outbreak of fungal meningitis associated with contaminated steroid injections from a compounding pharmacy, CDC and partners are studying long-term outcomes for those patients.

CDC, FDA, and state health departments investigated a fatal case of gastrointestinal mucormycosis caused by Rhizopus oryzae in a premature infant.

In the United States, the parasite Cryptosporidium sickens almost 750,000 people each year with watery diarrhea that can last for weeks. In 2010, CDC launched CryptoNet to collect Cryptosporidium DNA fingerprinting results. CryptoNet is the first tracking and DNA fingerprinting system for a disease caused by a parasite. It has provided valuable information on the different Cryptosporidium species infecting people in the United States.

Around the Globe

CDC Fights Cholera in Cameroon

Working with WHO and global partners, CDC helped Cameroon launch its largest oral cholera vaccine campaign, helping more than 127,000 at high risk of the disease.

Using Solar Energy to Treat Waste in Kenya

Refugee camps are often crowded, making it essential—but difficult—to provide adequate infrastructure for safe drinking water and sanitation. Solar sanitation is an inexpensive, innovative, and effective form of waste treatment that uses concentrated solar energy to treat waste so it can be safely discarded or potentially used for fertilizer or fuel. This is a critical component of a holistic waste management system that will ensure latrines are emptied, maintained clean, and reused—conserving space in the camp and reducing open defecation.

Defeating Diarrhea: CDC and Partners Tackle Causes and Consequences in Kenya and Beyond

“What if we lost 50 city buses full of children today?” asks Michael Beach, the associate director for healthy water in CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. “That’s 2,195 children—the number who die daily of diarrhea around the world. That’s more than die from AIDS, malaria, and measles combined.”

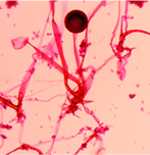

The fungus Cryptococcus causes life-threatening meningitis in hundreds of thousands of people every year. Most of these infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa. In countries with large populations of people living with HIV/AIDS, CDC is helping implement targeted cryptococcal screening programs and build laboratory capacity to detect cryptococcal infections early.

Outbreaks of histoplasmosis have been described in North, Central, and South America after activities that stir up soil or large amounts of bird or bat droppings. However, there had never been a known histoplasmosis outbreak in the Dominican Republic. In September 2015, a number of previously healthy young men were hospitalized with fever, headache, and cough, and the Dominican Republic Ministry of Health suspected the cause was histoplasmosis.

- Page last reviewed: October 26, 2015

- Page last updated: September 29, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir