Measles Travels from Malaysia to 10 States

Time is of the essence when measles is concerned. Responding to a measles outbreak can involve working 24/7. Measles is a highly contagious disease and can cause severe illness, even death.

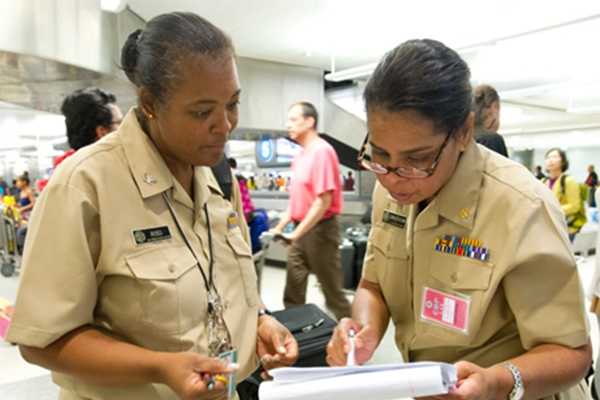

Keysha Ross and Kimberly Crocker, public health officers at the Los Angeles Quarantine Station, review flight information. Credit: CDC Foundation / David Snyder

What started as a routine call to the Los Angeles Quarantine Station (LAQS) involving one teenage refugee with measles quickly unfolded into an event where exposed passengers and refugees traveled to many states. Refugee travel from Malaysia to the United States was suspended for several weeks.

Located at 20 U.S. airports, seaports, and land border crossings, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Quarantine Stations serve on CDC’s frontlines to protect the public’s health at U.S. ports of entry. These stations connect locally with state and local health departments and globally with the ministries of health in various countries.

Staff at the quarantine stations work with partners to protect the health of communities from contagious diseases that are just a flight, cruise, or border crossing away. One of their many duties includes conducting investigations when an ill person onboard an airplane or ship may have infected others who need to be notified about their exposure.

One call takes on a life of its own, as a measles outbreak ripples out across the country.

“You never know when you get these calls. It’s amazing how within 24 hours a call can take on a life of its own,” said Kimberly Crocker, Officer in Charge of LAQS. “With the speed of travel and breadth of disease spread, one infected person can very quickly become 35. Picture a ripple effect.”

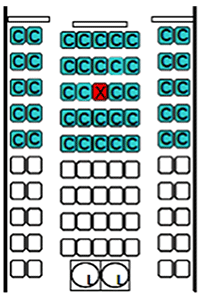

Seating diagram for notifying passengers exposed to measles, rubella, or tuberculosis. The red seat indicates the index case.

How it all began

The initial call on August 26, 2011, came from a California Department of Public Health officer who said that a refugee had been hospitalized with measles the day before. The teenager had just traveled from Malaysia on August 24. The health officer called the quarantine station because other passengers on the plane may have been exposed (contacts), and they needed to be notified. Juliana Berliet, quarantine public health officer, hung up the phone and initiated a flight contact investigation. She became the lead, coordinating the station staff and partners in this event.

Berliet called the airline to confirm where the ill teenager (index case) sat and requested the flight manifest, which provides passenger information. Thirty-five people who sat on the same row and two rows in front and back of the ill teenager were considered contacts. In addition, thirty refugees, who traveled from Malaysia as part of the same group as the teenager, were considered “travel companions” and therefore also exposed. The 35 passengers traveled on to 10 states, and the refugees traveled to 8.

Multistate investigation started

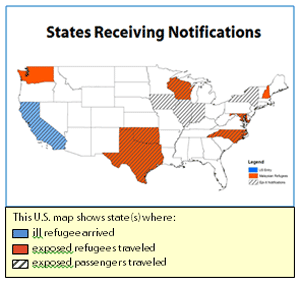

The CDC investigation crossed three time zones and involved several states: California, Washington, Texas, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Virginia, North Carolina, Maryland, New York, and New Hampshire. LAQS worked with 27 staff members at 3 CDC Quarantine Stations, Quarantine and Border Health Services Branch headquarters, the CDC Immigrant and Refugee Migrant Health Branch, CDC measles experts in Atlanta, and 12 state and county health departments. Notices went out to state health departments through Epi-X, a secure system CDC uses to notify states of people who have been exposed to diseases.

These agencies worked together to prevent further spread of measles in U.S. communities. All the contacts had to be evaluated quickly to make sure they were protected against measles and didn’t expose their families or members of their communities.

“It’s the crux of our program—unvaccinated travelers can spread disease,” said Crocker. “We worked closely with our partners throughout this event to ensure this didn’t happen.”

Other partners in this response included the airlines on which the ill teenager traveled, the Los Angeles County health department’s immunization program, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which coordinates the relocation of refugees. IOM was surprised that the ill teenager was not noticed before travel—it is rare for an ill refugee to be missed.

Recommendations provided

Six people in four states who were exposed to the ill teenager subsequently developed measles: three unvaccinated refugee children, two unvaccinated children who were passengers on the flight, and one unvaccinated Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer, who processed the flight. In addition, on September 7, 2011, the Wisconsin Department of Health notified the Chicago Quarantine Station of a measles case in an unvaccinated 23-month-old refugee from Malaysia who also traveled on August 24, but on a different flight.

To prevent further importation and transmission of measles from arriving Malaysian refugees, Martin S. Cetron, MD, Director of CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, issued a letter of recommendations to IOM and the Bureau of Population, Migration, and Refugees at the Department of State. He recommended temporarily stopping the refugee movement from Malaysia while U.S.-bound refugees were vaccinated for measles. The recommendation also included screening refugees for symptoms of measles before travel.

Training delivered

Because an unvaccinated CBP officer who processed the flight got sick with measles and was hospitalized, the LAQS staff trained CBP officers in recognizing the signs and symptoms of measles, as well as the importance and methods of minimizing exposure and spread. LAQS staff also provided a job aid on what to do if a CBP officer may have been exposed.

“You spend all this time developing relationships with partners, and at the end it really worked well,” said Crocker. “My own staff were incredibly responsive and flexible; they provided excellent coordination and worked late hours for conference calls and training. We all wanted to be here to answer questions asked by our partners.”

“Now, on to the next thing,” Crocker said with a smile.

- Page last reviewed: December 23, 2016

- Page last updated: December 23, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir