Human Factors Considerations in Addressing Mining Occupational Illness, Injuries and Fatalities

Authors

Dana Willmer, Emily Haas, and Lisa Steiner

Abstract

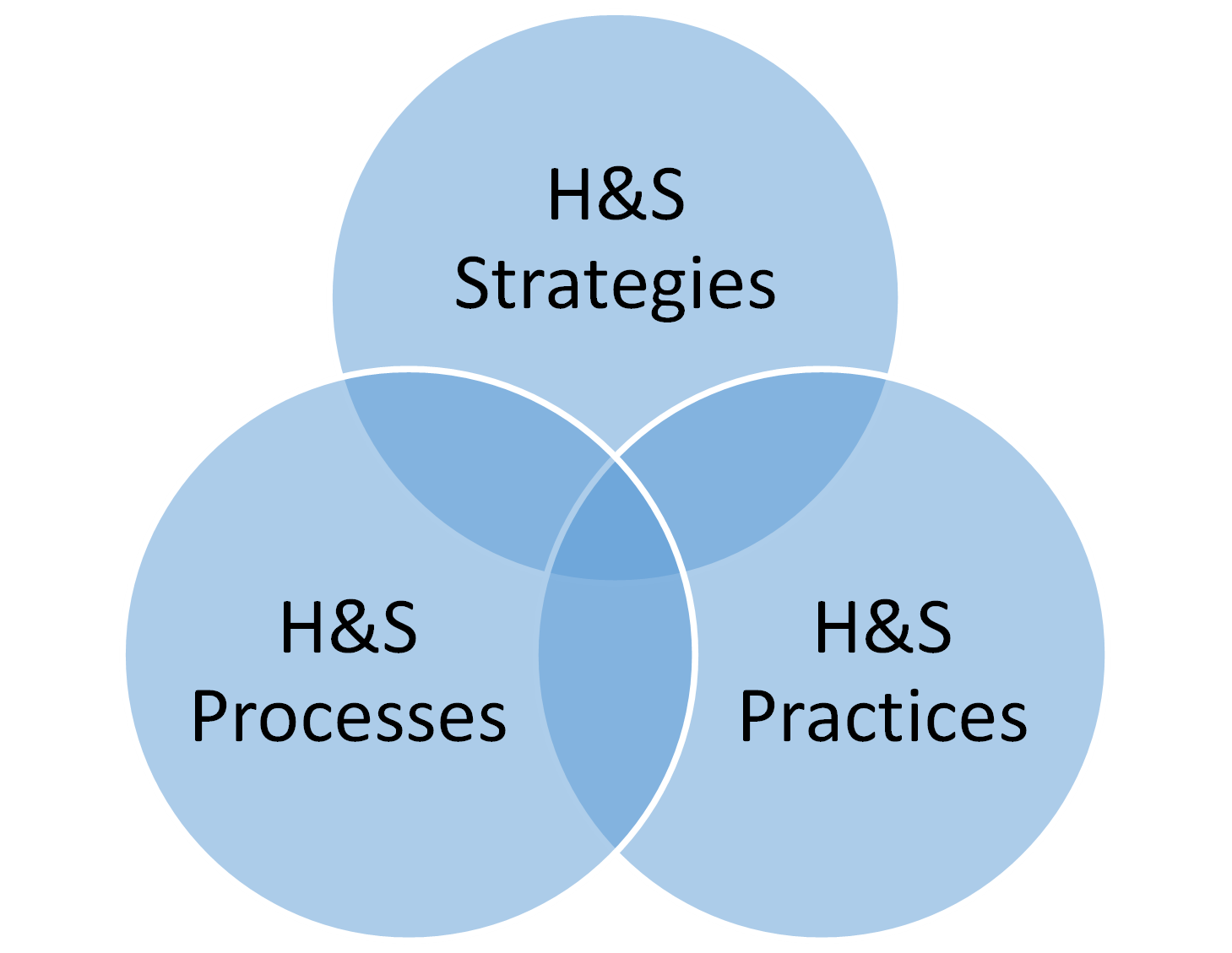

The combination of health and safety regulation and mining industry practices has resulted in a remarkable reduction in incidents, injuries and fatalities, but there is a persistent struggle to maintain or eliminate the individual or seemingly random events that lead to injuries and disease. When viewed as a single event, a mischaracterization of root cause is likely. When viewed collectively, these individual events often have common factors that can be examined on a larger scale. Occupational health and safety research often focuses on events separately but recognizes the need for integrating the study of safe work strategies, process and practices/behaviors to create a safe work place. Studying how to create a safe mining work place requires an integrated research view and characterization of the influencers of the mining work place. The mining research program has a 40-year history of using a human factors systems approach to identify, characterize, mitigate, and respond to hazards, risks, and emergencies in the mining environment. This systems approach extends beyond the mineworker and includes others in the mining organization and beyond, that can influence health and safety (H&S). As an integrated research perspective, drawn from public health models, NIOSH mining’s human factors approach considers how the mining workplace (or work operation) is shaped by regulatory and industry perspectives that get integrated with a mine company’s culture, resources and practices. Additionally, the mine work site is also shaped by the dynamics of human behavior that influence decision-making, actions and behaviors of leaders and workers in their day-to-day work performance. Studying the mining system’s influencers uncovers deficiencies, missed interactions and gaps that lead to incidents. Identifying and evaluating these influencers informs the development of guidance, interventions, evaluations and optimization strategies that can be integrated into the mining industry’s systematic management of health and safety through safe strategies, safe processes and safe practices/behaviors in the prevention of future incidents, injuries, diseases and fatalities.

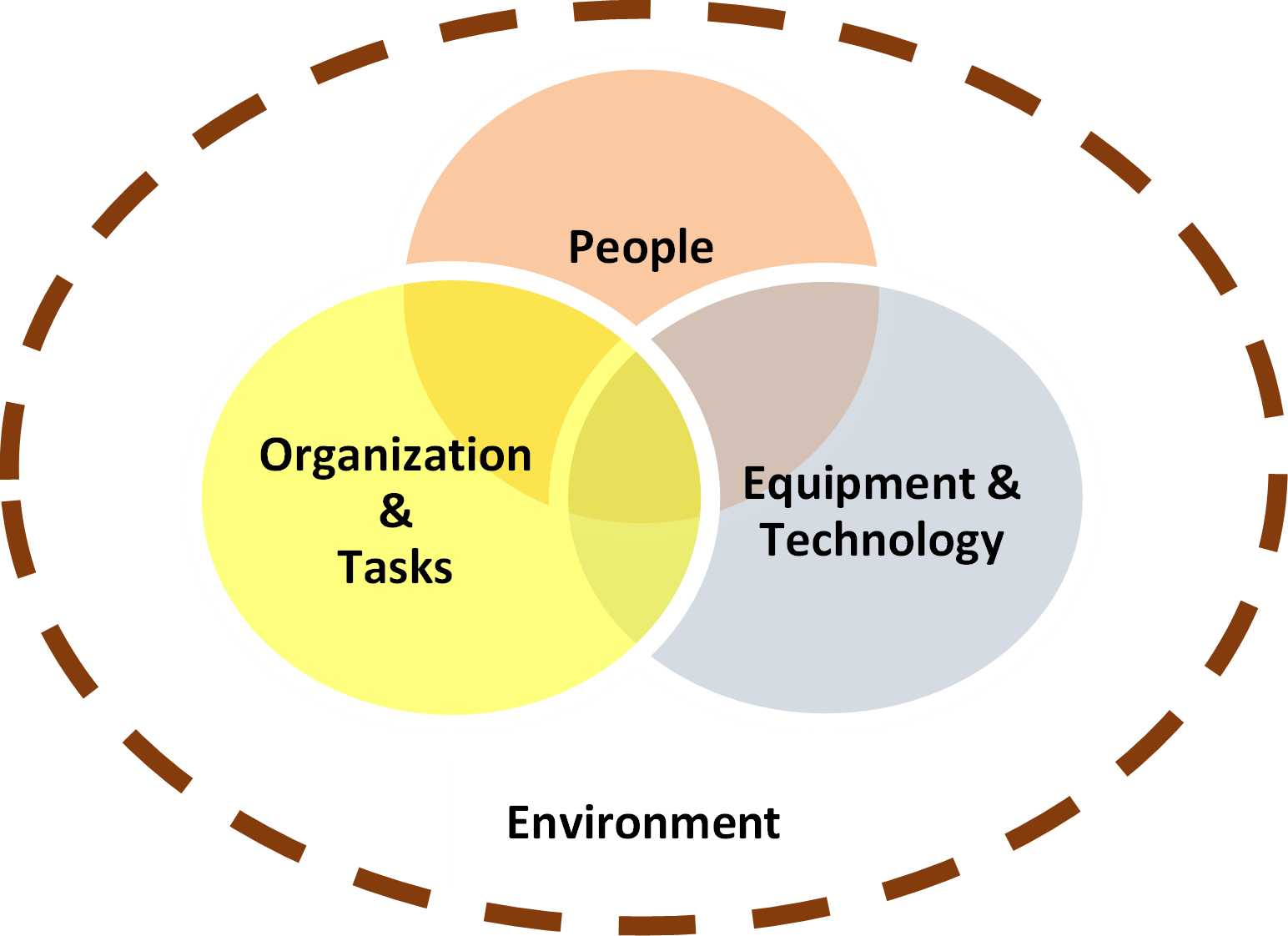

The Human Factors systems research approach aims to improve and sustain individual and organizational well-being and optimize overall system performance. Research characterizes (1) how individuals interact and behave in relation to varying aspects of a mine environment; (2) how routine and new work processes, including new technologies, influence risk perception, attitudes, decision making, and behaviors in the mine environment; and (3) how organizations manage and evaluate these individuals and processes through the execution of their health and safety management systems.

The Role of Humans: Determining Root Cause in Accidents

Often the question is asked, what is the role of the human and human behavior in being the root cause of accidents? Just as there can be many root causes there are many root cause assessment frameworks (each with its own analytical strengths and limitations). In one study, Sanders & Shaw attempted to identify the root causes of incidences under a U.S. Bureau of Mines contract. Sanders and Shaw’s report[i] summarizes their findings. The researchers assessed the extent to which various types of factors contributed to 338 accidents in U.S. underground coal mines. Raters assessed the degree to which each of ten types of potential causal factors played a role in each accident. Researchers concluded that “human” error of the injured employee was involved to some degree in 93% of the cases and when involved, averaged about 33 (of 100) points of causality. The factor was considered a primary causal factor in almost 50% of the cases and a secondary causal factor in another 24%. Management was the second most important causal factor. It was considered a primary factor in 22% of the cases and a secondary factor in another 12%. A second and more recent root cause assessment study on fatalities from 2005-2015 by Burgess-Limerick (2016) shows a behavioral component to most fatalities (as described in the MSHA fatality reports) among many other human-related root causes such as poor design and lack of technology and training[ii]. In determining how to address these root causes NIOSH human factors studies use a systems approach focusing on the interactions and influencing characteristics between a mine organization’s strategic development and management of H&S strategies; design, execution and implementation of H&S operational processes; and decision making and performance of worker H&S behaviors and practices to prevent future incidents, injuries, disease and fatalities. Our research studies produce guidance, interventions, technologies, tools and training to promote safe strategies, safe processes and safe practices/behaviors.

Safe Strategies

Systematically managing occupational H&S risks is a minimum requirement at every mine. As early as 2006, the National Mining Association (NMA) asserted that every mine should conduct, employ, and evaluate a risk-analysis process. Then in 2010, a Federal Register Notice (75 FR 68224) proposed that industries develop and implement a Health and Safety Management System (HSMS) to improve overall performance. More recently, in May 2015, the Assistant Secretary for the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) urged stakeholders to “strengthen existing safety and health management programs.” However, the time and cost involved in developing, implementing, and evaluating an effective HSMS framework remains a challenge for the mining industry. As a result, a focus on identifying and characterizing necessary aspects of an HSMS, pragmatic approaches for implementing a consistent execution of H&S practices, and continually evaluating the performance of the HSMS and making changes as needed to continue supporting worksite performance, are key problems that inform NIOSH’s focus.

A systems approach to managing health and safety is not exclusive to the everyday mining workplace. Human factors research also conducts studies with a focus on non-routine occupational circumstances and activities—especially those that are serious, unexpected, dangerous, and require immediate action— to increase the likelihood of successful performance in mine emergency mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. Several additional layers of groups and subsystems exist exclusively in the mine emergency system, including mine rescue teams, command centers, and emergency communication and tracking systems.

Select NIOSH Mining publications on Safe Strategies:

- Exploring the State of Health and Safety Management System Performance Measurement in Mining Organizations. Saf Sci 2016 Mar; 83:48-58. Peer Reviewed Journal Article. Haas EJ and Yorio PL.

- Health and safety management systems through a multilevel and strategic management perspective: Theoretical and empirical considerations. Safety Science 72 (2015) 221–228. Accepted 13 September 2014. Yorio PL, Willmer DR, Moore S.

- Interpreting MSHA citations through the lens of occupational health and safety management systems: investigating their impact on mine injuries and illnesses 2003-2010. Risk Anal 2014 Aug; 34(8):1538-1553. ISSN 0272-4332. Yorio PL, Willmer DR, Haight JM. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nioshtic-2/20043761.html

Safe Processes

NIOSH mining research studying human factors also examines the role of poor design of equipment, environment, process, or technology as a root cause of illness, injury and fatality. Appropriate design accounts for human use and misuse of a system, as well as, their abilities and limitations. User centered is incorporated into the concept/ideation level of products and processes by understanding the risks, functions, and the environment in which the tasks are performed and then applying the appropriate principles for safe-by-design. In the mining industry machine-related accidents are prevalent, with 41% of serious mining incidents involving equipment from 2000-2007[iii], [iv]. Additionally, most fatalities involve mining equipment[v], [vi], [vii]. Human-centered designs, human interfaces, and technology integration are critical elements of human-machine integration that can reduce the risks associated with mining machinery. Besides human factors such as age, physical size, background, attitude, and skills, there are also many organizational factor variations. It is essential to understand these factors to determine human capabilities and limitations while working with or near machinery in the mining environment.

Select NIOSH Mining publications on Safe Processes:

- A Different Perspective: NIOSH Researchers Learn from CM Operator Responses to Proximity Detection Systems. Coal Age 2015 Oct; 120(10):34-35. Haas EJ and DuCarme JP.

- Formative Research to Reduce Mine Worker Respirable Silica Dust Exposure: a Feasibility Study to Integrate Technology into Behavioral Interventions. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016 Feb; 2:6. Haas EJ, Willmer DR, Cecala AB.

- Application of Fatigue Management Systems and Small Mines and Low Technology Solutions. Min Eng 2014 Apr; 66(4):69-75. Eiter B, Steiner LJ, Kelhart A.

Safe Practices

Results from National Academy of Science (NAS) panels in 2013 and 2014 called for efforts that focused on mineworkers’ abilities to recognize site-specific hazards [viii]. For example, the 2013 report suggested using decision science research to develop protocols and training materials to enhance miners’ attention to unexpected risks, situational awareness, and competence. Hazard recognition is integral to risk perception, situational awareness, and decision-making. If a mineworker is unable to recognize hazards then they cannot take steps to eliminate or mitigate them. NIOSH has completed much research to provide insight into hazard recognition and mitigation to reduce injuries at mines.

The NIOSH mining program has also completed several multi-level interventions that include components of behavior modification to reduce health and safety risks. In one study, interventions with 48 mineworkers at five industrial mineral/metal mine sites were completed in 2015 and 2016 to study how to effectively integrate, via a HSMS framework, a non-regulated technology to help assess exposure to respirable dust. Initial results have shown a statistically significant increase in workers’ proactive behaviors. However, this same research, when conducting six-month follow-ups, shows that maintenance of these behaviors is short-lived and site-level leadership must continue to communicate with workers to provide resources that further support the maintenance of health and safety behaviors over a period. Interviews, with mineworkers in various commodities, have revealed information about perceived barriers to H&S behaviors on the job. Researchers within the program have been able to characterize and generalize these barriers (i.e., underestimating negative outcomes, high levels of risk tolerance, complacency on the job, and a sense of hopelessness) to inform current and future research. Specifically, the NIOSH mining program has been able to implement behavioral interventions, grounded in health and safety management elements and practices, to minimize workers’ perceived barriers through technology application and leadership practices as exuded by management.

Select NIOSH Mining publications on Safe Practices:

- Using CPDM Dust Data. Coal Age 2016 Feb; 121(2):40-41. Haas EJ, Willmer D, Meadows JJ.

- Moving Beyond Mandated Training: Preparing Mine Rescue Teams for Peak Performance. Coal Age Thursday, 01 September 2016 10:22. Hoebbel C, Bauerle T, Mallett L, and Macdonald B. http://www.coalage.com/features/5364-moving-beyond-mandated-training.html#.WOZj_sJU270

- Defining Hazard from the Mine Worker's Perspective. Min Eng 2016 Nov; 68(11):50-54. Peer Reviewed Journal Article. Eiter B, Kosmoski C, Connor BP.

- Training and evaluation of coal miners’ self-escape competencies. Coal Age, Published: Monday, 21 September 2015 15:56. Haas EJ and Peters RH. http://www.coalage.com/features/4700-training-and-evaluation-of-coal-miners-self-escape-competencies.html#.WOZwW8JU270

Additional NIOSH publications related to Strategies, Processes, and Practices available upon request.

[i] Sanders M., Shaw B. (1988). Research to determine the contribution of system factors on the occurrence of underground injury accidents. (Contract J0348042). Pittsburgh, PA: Bureau of Mines

[ii] Robin Burgess-Limerick (2016) Bowtie Analysis of Mining Fatalities to Identify Priority Control Technologies, Minerals Industry Safety and Health Centre Sustainable Minerals Institute, The University of Queensland, Australia. Report for NIOSH contract 200-2015-M-62391and contract 200-2014-M-59063

[iii] MSHA (2012). MSHA Data Files for Coal Industry Sector. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining/statistics/CoalSector.html. Handling Materials = 30.8%, Machinery = 11.4%, Powered Haulage = 11.3%, Hand Tools = 5.9%. Total lost-time injuries 2008-2012 = 10,211 (years 2008-2012)

[iv] Moore, S., Dempsey, P., Sammarco, J., Ruff, T., Carr, J., Porter, W., & Reyes, M. (2012). Understanding and Mitigating Equipment-Related Injuries. In J. Bhattacharya (Ed.), Design and Selection of Bulk Material Handling Equipment and Systems: Mining, Mineral Processing, Port, Plant and Excavation Engineering (1 ed., Vol. 2, pp. 252): Wide Publishing.

[v] Ruff, T., Coleman, P., & Martini, L. (2011). Machine-related injuries in the US mining industry and priorities for safety research. International journal of injury control and safety promotion, 18(1), 11-20.

[vi] Groves, W. A., Kecojevic, V. J., & Komljenovic, D. (2007). Analysis of fatalities and injuries involving mining equipment. J Safety Res, 38(4), 461-470. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2007.03.011

[vii] Kecojevic, V., Komljenovic, D., Groves, W., & Radomsky, M. (2007). An analysis of equipment related fatal ask accidents in US mining operations: 1995-2005. Safety science, 45, 864-874.

[viii] National Research Council. (2013). Improving Self-Escape from Underground Coal Mines. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Additional Selected NIOSH Mining Human Factors Guidance, Interventions, Tools, and Training

Age Awareness Training for Miners. NIOSH 2008 Jun; :1-125. Numbered Publication; Information Circular. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2008-133; IC-9505. Porter WL, Mallett LG, Schwerha DJ, Gallagher S, Torma-Krajewski J, Steiner LJ.

Aggregate Training for the Safety Impaired. DHHS (NIOSH) Video; Numbered Publication. Publication No. 2007-134d. NIOSH 2007 Apr. Cullen E.

Arc Flash Awareness. Numbered Publication; Video. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2007-116D. NIOSH 2007 Jan. Kowalski-Trakofler KM; Barrett EA; Urban C; Homce G.

Interactive BG 4 Training Software Reinforces Skills for Benching Mine Rescue Breathing Apparatus. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2015-225, TN 553, 2013 Aug; :1-2. Navoyski J, Brnich MJ, Bauerle TJ.

Blast Area Security. Beaver, WV: U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, National Mine Health and Safety Academy. DVD 568, 2006 Jan; :Video. Harris M.

Emergency Escape and Refuge Alternatives: Instructor Guide and Lesson Plan. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011-101, (IC 9525), 2010 Oct; :1-17. Hall EE and Margolis KA.

Ergonomics and Risk Factor Awareness Training for Miners. NIOSH 2008 Jul; :1-182. Numbered Publication; Information Circular. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2008-111; IC-9497. Torma-Krajewski J, Steiner LJ, Unger RL, Wiehagen WJ.

ErgoMine. Version: 1.0. Software (Android) Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH), 2016 Apr. Dempsey PG, Pollard JP, Porter WL, Mayton AG, Heberger J, Reardon L, Fritz JE, Young M.

Escape from Farmington No. 9: An Oral History. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication 2009-142D, 2009 May; DVD. Numbered Publication. Brnich MJ and Vaught C.

EVADE Software. Version 2.0. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2014-134c, 2016 Dec. Cecala AB, Cole GP, Reed WR, Britton J.

Harry's Hard Choices: Mine Refuge Chamber Training. Instructor's guide and trainee's problem booklet. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2009-122 (IC 9511), 2009 Mar; :1-34. Numbered Publication; Information Circular. Vaught C, Hall EE, Klein KA.

Heat Stress: A Series of Fact Sheets for Promoting Safe Work in Hot Mining Settings. Spokane, WA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication Nos. 2017-123; 2017-124; 2017-125; 2017-126; 2017-127; 2017-128. Victoroff T and Yeoman K.

HLSim - NIOSH Hearing Loss Simulator. NIOSH 2010 Dec; :CD-ROM. Version: 3.0.1215.1. NIOSH.

How to Operate a Refuge Chamber: a Quick Start Guide. Instructor Guide and Lesson Plan. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011-100 (IC 9524), 2010 Oct; :1-20. Numbered Publication; Information Circular. Hall EE and Margolis KA.

How to use the Coal Dust Explosibility Meter. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Videos. OMSHR 2013 April.

Keeping Knees Healthy in Restricted Work Spaces: Applications in Low-Seam Mining. NIOSH 2008 May; 1-16. Numbered Publication; Information Circular. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2008-130; IC-9504. Moore SM, Steiner LJ, Nelson ME, Mayton AG, Fitzgerald GK.

Lifeline Tactile Signal Flashcards. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2011 Aug. Kingsley Westerman CY, Kosmoski CL.

Man Mountain’s Refuge: Refuge Chamber Training Instructor’s Guide and Trainee’s Problem Book. Report of Investigations 2011. Pittsburgh, PA: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011-195, RI 9685, 2011 Jul; :1-32.

Nonverbal Communication for Mine Emergencies: Instructors Guide. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2012-104, RI 9688, 2012 Jan; :1-17. Kosmoski CL, Margolis KA, Kingsley Westerman CY, Mallett L.

Radio 101: Operating Two-Way Radios Every Day and in Emergencies - instructor's guide. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011-203I, 2011 Aug; :1-20. Kingsley Westerman CY, Brnich MJ, Kosmoski C.

Reducing Dust Inside Enclosed Cabs. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2009-121D, 2009 Mar: ;7 minutes. Cecala AB, Organiscak JA, Taylor C, Urban CW.

Refuge Chamber Expectations Training: Instructor Guide and Lesson Plans. Version: 1.0. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2010-100, Information Circular 9516, 2009 Oct; :1-18. Margolis KA, Kowalski-Trakofler KM , Kingsley Westerman CY.

Safety and Health Toolbox Talks: When and where you need them. Version 1.0. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2016 Aug: web software. Eiter B, Mallett LG, Heberger JR.

Underground Coal Mine Map Reading Training. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2009-143c, 2009 May; :CD-ROM. NIOSH.

What Does a Hearing Loss Sound Like? NIOSH Hearing Loss Simulator. Sound samples MP3 format.

When Do You Take Refuge? Decision Making During Mine Emergency Escape: computer-based training program. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Report of Investigations. Publication No. 2011-177C, 2011 Aug; :CD-ROM. Kosmoski CL, Margolis KA, McNelis KL, Brnich MJ, Mallet L, Lenart P.

Safety Pays in Mining: Users Guide and Technical Guide. Version: 1.2.

See Also

- An Analysis of Health and Safety Management Systems in Mining

- Assessing and Evaluating Human Systems Integration Needs in Mining

- Considerations in Training On-the-Job Trainers

- Mining Publications List: 1995 - 1999

- Optimizing Secondary Roof Support with the NIOSH Support Technology Optimization Program (STOP)

- Preventing Equipment Related Injuries in Underground U.S. Coal Mines

- Programmable Electronic Mining Systems: Best Practice Recommendations (In Nine Parts): Part 2: 2.1 System Safety

- Programmable Electronic Mining Systems: Best Practice Recommendations (In Nine Parts): Part 4: 3.0 Safety File

- Technology News 513 - Coaching Workshop for On-the-Job Trainers

- Toolbox Training on Flyrock Awareness

- Page last reviewed: 5/10/2017

- Page last updated: 5/10/2017

- Content source: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Mining Program

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir