Drug Resistance

Antibiotics are medicines used to kill the bacteria that cause disease. However, bacteria can change—or mutate—making it possible to resist antibiotics. Public health experts call this antibiotic resistance. Many bacteria, including some Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), have become resistant to one or more antibiotics. Resistance can lead to treatment failures.

Background

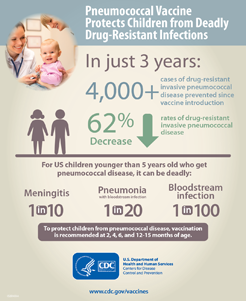

Until 2000, pneumococcal infections caused 60,000 cases of invasive disease each year. Up to 40% of these infections were caused by pneumococcal bacteria that were resistant to at least one antibiotic.[1] These numbers have decreased greatly following:

- The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for children

- A change in definition of non-susceptibility (resistance) to penicillin in 2008[2]

In 2015, there were about 30,000 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease.[3] Available data show that pneumococcal bacteria are resistant to one or more antibiotics in 30% of cases.[4, 5] How common drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (DRSP) is depends on what part of the country you live in.

Larger view

Reference: Tomczyk S, Jorgensen J, Lynfield R, et al. Prevention of antimicrobial-resistant infection among children aged <5 years with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine – selected U.S. areas, 2009-2013. Paper presented at: IDWeek 2014. 2014 Oct 8-12; Philadelphia, PA.

Trends

There are more than 90 strains (serotypes) of pneumococcus bacteria. Seven serotypes (6A, 6B, 9V, 14, 19A, 19F, and 23F) accounted for most DRSP before the introduction of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7, Prevnar®) in the United States in 2000. After PCV7 introduction, most antibiotic resistance was found in serotype 19A, which is included in the newer 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13®) introduced in the United States in February 2010 and currently being used.

Both PCV7 and PCV13 prevented many infections due to drug-resistant pneumococcal strains.

State and local health departments have reported outbreaks of DRSP in nursing homes, institutions for HIV-infected persons, and childcare centers.

Costs

DRSP is associated with increased costs compared to infections caused by non-resistant (susceptible) pneumococcus. This is because of

- The need for more expensive antibiotics, new antibiotic drug development, and for surveillance to track resistance patterns

- Repeat disease due to treatment failures

- Educational requirements for patients, physicians, and microbiologists

Risk Groups

If you attend or work at childcare centers, you are at increased risk for infection with DRSP. Among those with pneumococcal infections, those who recently used antibiotics are more likely to have a resistant infection than those who have not.

Surveillance

CDC sponsors the Active Bacteria Core surveillance (ABCs), an active, population-based surveillance system in 10 states. In addition, all types of invasive pneumococcal disease (including DRSP) are included in the national public health surveillance system. Several private-sector systems also track DRSP.

Prevention: Challenges and Opportunities

There are several factors that create challenges for preventing emerging drug resistance of pneumococcus, including:

- Widespread overuse of antibiotics

- Spread of resistant strains

- Underuse of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) recommended for adults at increased risk

- Lack of adoption by some clinical laboratories of standard methods (NCCLS guidelines) for identifying and defining DRSP

- Lack of vaccine availability to protect against all strains of pneumococcus

Campaigns for more judicious use of antibiotics and expanded use of vaccines may slow or reverse emerging drug resistance. Prevention of infections could improve through expanded use of PPSV23 and PCV13.

References

- Active Bacterial Core surveillance, 1996-2015.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; eighteenth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S18. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Report, Emerging Infections Program Network, Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013.

- Kim L, McGee L, Tomczyk S, Beall B. Biological and epidemiological features of antibiotic-resistance Streptococcus pneumoniae in pre- and post-conjugate vaccine eras: A United States perspective. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29(3):525–52.

- Page last reviewed: September 6, 2017

- Page last updated: September 6, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir