Cigarette Smoking and Tobacco Use Among People of Low Socioeconomic Status

Adults who have lower levels of educational attainment, who are unemployed, or who live at, near, or below the U.S. federal poverty level are considered to have low socioeconomic status (SES).1

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the poverty rate in 2014 was 14.8%.2 In 2014, the number of people aged 18 and older who had completed only high school was 29.6%, and the number who had completed high school up to grade 11 but had no diploma was 4.4%.3

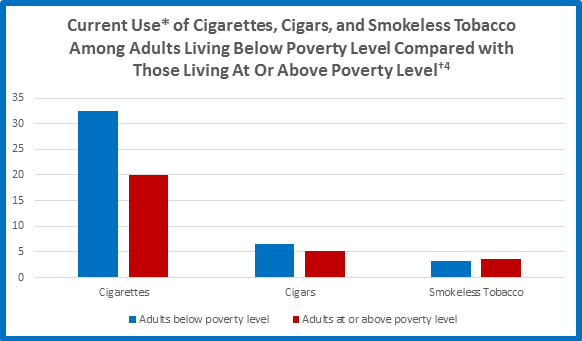

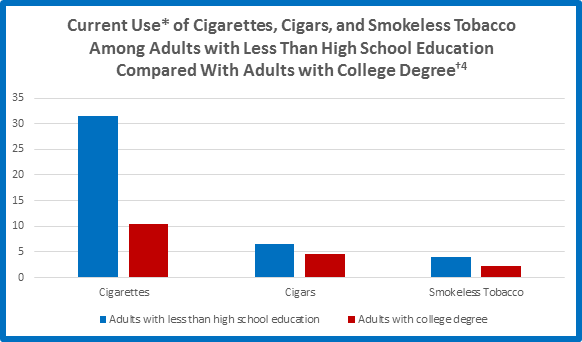

In the U.S., people living below the poverty level and people having lower levels of educational attainment have higher rates of cigarette smoking than the general population.4,5 Among people having only a GED certificate, smoking prevalence is more than 40%, the highest of any SES group.5

Tobacco Use Prevalence

* “Current Use” is defined as self-reported consumption of cigarettes, cigars, or smokeless tobacco in the past 30 days (at the time of survey).

† Data taken from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2012, and refer to adults aged 18 years and older.

Health Effects

Cigarette smoking disproportionately affects the health of people with low SES. Lower income cigarette smokers suffer more from diseases caused by smoking than do smokers with higher incomes.6

- Populations in the most socioeconomically deprived groups have higher lung cancer risk than those in the most affluent groups.7

- People with less than a high school education have higher lung cancer incidence than those with a college education.6,8

- People with family incomes of less than $12,500 have higher lung cancer incidence than those with family incomes of $50,000 or more.8

- People living in rural, deprived areas have 18–20% higher rates of lung cancer than people living in urban areas.7

- Lower-income populations have less access to health care, making it more likely that they are diagnosed at later stages of diseases and conditions.6

Patterns of Cigarette Smoking

People with low SES tend to smoke cigarettes more heavily.

- People living in poverty smoke cigarettes for a duration of nearly twice as many years as people with a family income of three times the poverty rate.9

- People with a high school education smoke cigarettes for a duration of more than twice as many years as people with at least a bachelor’s degree.9

- Blue-collar workers are more likely to start smoking cigarettes at a younger age and to smoke more heavily than white-collar workers.10

Secondhand Smoke Exposure

Secondhand smoke exposure is higher among people living below the poverty level and those with less education.11

- Low SES populations are more likely to suffer the harmful health consequences of exposure to secondhand smoke.11

- Blue-collar workers are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke at work than white-collar workers.10

- Service workers, especially bartenders and wait staff, report the lowest rates of workplace smoke-free policies than other occupation categories.12

Quitting Behavior

People of low SES are just as likely to make quit attempts but are less likely to quit smoking cigarettes than those who are not.4

- An estimated 66.6% of adult current daily cigarette smokers living below the poverty level attempt to quit smoking cigarettes compared with 69.9% of those living at or above the poverty level.4

- An estimated 39.0% of adult current daily cigarette smokers with no high school diploma attempt to quit smoking compared with 44.0% of those with some college education.4

- Adults who live below the poverty level have less success in quitting (34.5%) than those who live at or above the poverty level (57.5%).4

- Adults with less than a high school education (9–12 years, but no diploma) have less success in quitting (43.5%) than those with a college education or greater (73.9%).4

- Blue-collar and service workers are less likely to quit smoking than white-collar workers.10

Tobacco Industry Marketing and Targeting

Tobacco companies often target their advertising campaigns toward low-income neighborhoods and communities.4

- Researchers have found a higher density of tobacco retailers in low-income neighborhoods.13

- Tobacco companies have historically targeted women of low SES through distribution of discount coupons, point-of-sale discounts, direct-mail coupons, and development of brands that appeal to these women.14

Culturally appropriate anti-smoking health marketing strategies and mass media campaigns like CDC’s Tips From Former Smokers national tobacco education campaign, as well as CDC-recommended tobacco prevention and control programs and policies, can help reduce the burden of disease among people of low SES status.

Resources

Publication

Website

References

- Garrett BE, Dube SR, Trosclair A, Caraballo RS, Pechacek TF. Cigarette Smoking—United States, 1965-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Supplements 2011; 60(01):109-13 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty: 2014 Highlights. Last updated 2015 Sep 25 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- U.S. Census Bureau. Educational Attainment in the United States: 2014—Detailed Tables. Last updated 2015 Jan 05 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005-2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2015;64(44):1233-40 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Tobacco and Socioeconomic Status [PDF–56.2 KB]. Washington, D.C.: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, 2015 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, Rural-Urban, and Racial Inequalities In US Cancer Mortality: Part I—All Cancers and Lung Cancer and Part II—Colorectal, Prostate, Breast, and Cervical Cancers. Journal of Cancer Epidemiology 2011; doi.org/10.1155/2011/107497 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Singh GK, Lin YD, et al. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Cancer Incidence and Stage at Diagnosis: Selected Findings from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes and Control 2009;20(4) [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Siahpush M, Singh GH, Jones PR, Timsina LR. Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Variations in Duration of Smoking: Results from 2003, 2006 and 2007 Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey. Journal of Public Health 2009;32(2):210-8 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Ham DC, Przybeck T, Strickland JR, Luke DA, Bierut LJ, Evanoff BA. Occupation and Workplace Policies Predict Smoking Behaviors: Analysis of National Data from the Current Population Survey. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2011;53(11):1337-45 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Disparities in Nonsmokers’ Exposure to Secondhand Smoke—United States, 1999–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2015;64(04):103–8 [accessed 2016 Mar 29].

- Arheart KL, Lee DJ, Dietz NA, Wilkinson JD, Clark III JD, LeBlanc WG, Serdar B, Fleming LE. Declining Trends in Serum Cotinine Levels in U.S. Worker Groups: The Power of Policy. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2008;50(1):57–63 [cited 2016 Mar 29].

- Yu D, Peterson NA, Sheffer MA, Reid RJ, Schneider JE. Tobacco Outlet Density and Demographics: Analysing the Relationships with a Spatial Regression Approach. Public Health, 2010;124(7):412–6 [cited 2016 Mar 29].

- Brown-Johnson CG, England LJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Tobacco Industry Marketing to Low Socioeconomic Status Women in the USA. Tobacco Control. Published online first: 2014 Jan 21, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051224 [cited 2016 Mar 29].

For Further Information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Office on Smoking and Health

E-mail: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Phone: 1-800-CDC-INFO

Media Inquiries: Contact CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health press line at 770-488-5493.

- Page last reviewed: February 3, 2017

- Page last updated: February 3, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir