Pregnant Women and Tdap Vaccination, Internet Panel Survey, United States, April 2016

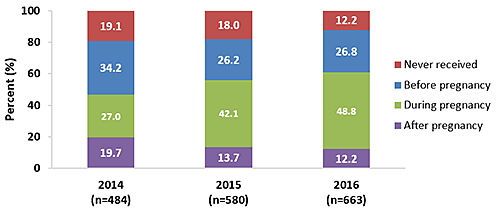

Figure 1.

Receipt of most recent Tdap vaccination among recently pregnant women who had a live birth, Internet panel surveys, United States, April 2014, April 2015, and April 2016

Pertussis (whooping cough) is a contagious respiratory illness that can lead to hospitalization and death, especially among infants <12 months of age [1,2]. The best way to protect infants who are too young to be vaccinated against whooping cough,* is for their mothers to get a tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during pregnancy [3]. Infants whose mothers get a Tdap vaccination while pregnant have a lower risk of getting whooping cough and related complications early in life [3–9].

Since late 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics have recommended that women receive a Tdap vaccination during every pregnancy, optimally at 27 through 36 weeks of gestation [3–5,7].

To estimate Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women, CDC analyzed data on Tdap vaccination from an Internet panel survey. The survey was conducted March 29 through April 7, 2016, among women who were pregnant any time since August 2015. Women who had delivered a live infant by the time of the survey and who knew their vaccination status were included in the analysis. Differences of at least 5 percentage points between estimates are noted.

Key Findings

- In 2016, Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy among women who had a live birth was 48.8%, an increase compared with 2015 vaccination coverage (42.1%).

- The proportion of recently pregnant women who received their most recent Tdap vaccination before or after pregnancy was similar in 2016 (39.0%) compared with 2015 (39.9%).

- The proportion of recently pregnant women who reported never receiving a Tdap vaccination decreased in 2016 (12.2%) compared with 2015 (18.0%).

- Among respondents in the 2016 survey, 63.6% received an offer of Tdap vaccination from a doctor or other medical professional, 13.2% received a recommendation for but no offer of vaccination, and 23.2% did not receive a recommendation for Tdap vaccination.

- Women who received a recommendation for and an offer of Tdap vaccination were more likely to be vaccinated during pregnancy.

- These women were more than two times more likely to be vaccinated during pregnancy compared with women who received only a recommendation for vaccination but no offer of vaccination (69.9% versus 30.8%).

- They were nearly 50 times more likely to be vaccinated compared with women who did not receive a recommendation for vaccination (69.9% versus 1.4%).

Conclusion/Recommendation:

- Health care personnel (HCP) are encouraged to strongly recommend and offer Tdap vaccination to pregnant women during every pregnancy, preferably during the early part of gestational weeks 27 through 36, to help prevent whooping cough in their infants [3,10].

Who Was Vaccinated?

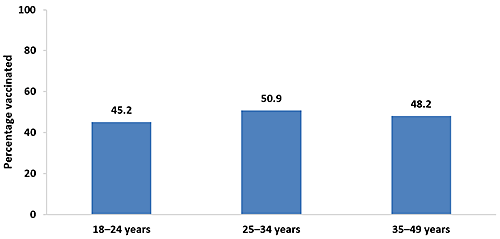

Coverage During Pregnancy by Age Group

- In 2016, pregnant women 18–24 years (45.2%) were less likely to be vaccinated than pregnant women 25–34 years (50.9%).

- Coverage was higher in 2016 compared with 2015 among pregnant women 25–34 years (50.9% vs. 43.0%) and 35–49 years (48.2% vs. 41.0%).

Figure 2.

Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy among recently pregnant women who had a live birth,† by age, Internet panel survey, United States, April 2016 (n=663)

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations | Sample Sizes | Previous Year

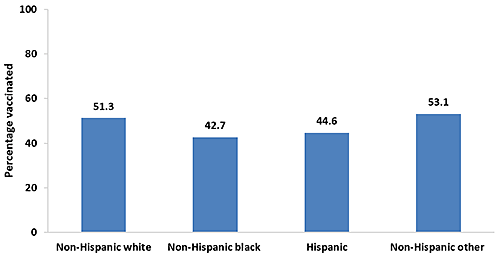

Coverage During Pregnancy by Race/Ethnicity‡

- In 2016, Tdap vaccination coverage among non-Hispanic white (51.3%) and non-Hispanic women of other race (53.1%) was higher compared with non-Hispanic black (42.7%) and Hispanic women (44.6%).

- Coverage was higher in 2016 compared with 2015 among non-Hispanic white (51.3% vs. 42.2%) and non-Hispanic women of other race (53.1% vs. 47.4%).

Figure 3.

Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy among recently pregnant women who had a live birth,† by race/ethnicity,‡ Internet panel survey, United States, April 2016 (n=663)

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations | Sample Sizes | Previous Year

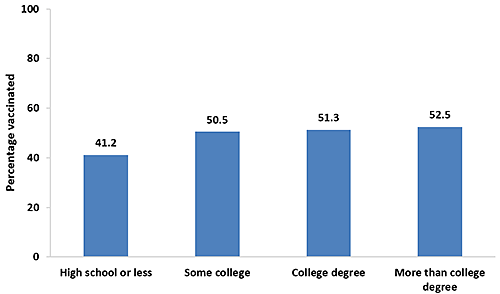

Coverage During Pregnancy by Education

- In 2016, Tdap vaccination coverage was lower among pregnant women with a high school diploma or less (41.2%) compared with women with some college education (50.5%), women with a college degree (51.3%), and women with more than a college degree (52.5%).

- Coverage was higher in 2016 compared with 2015 among women with some college education (50.5% vs. 41.2%), women with a college degree (51.3% vs. 38.6%), and women with more than a college degree (52.5% vs. 44.6%), but lower among women with a high school diploma or less (41.2% vs. 47.4%).

Figure 4.

Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy among recently pregnant women who had a live birth,† by education, Internet panel survey, United States, April 2016 (n=663)

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations | Sample Sizes | Previous Year

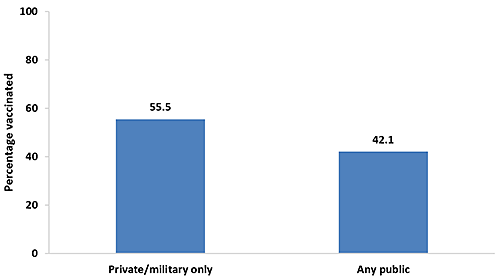

Coverage During Pregnancy by Type of Medical Insurance§

- In 2016, pregnant women who reported having private/military medical insurance as their only insurance during pregnancy had higher vaccination coverage (55.5%) than women who reported having any type of public medical insurance (42.1%).

- Tdap vaccination coverage was higher in 2016 compared with 2015 among women who had only private/military insurance (55.5% vs. 45.5%).

Figure 5.

Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy among recently pregnant women who had a live birth,† by type of medical insurance,§ Internet panel survey, United States, April 2016 (n=648)

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations | Sample Sizes | Previous Year

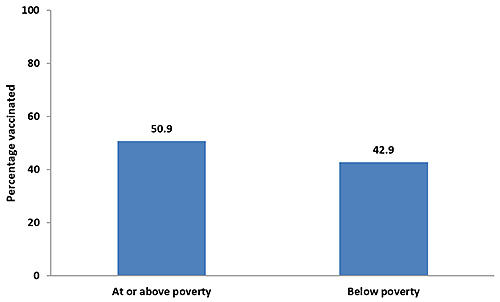

Coverage During Pregnancy by Poverty Status||

- In 2016, pregnant women who were living below the poverty level (42.9%) had lower vaccination coverage compared with women who were living at or above the poverty level (50.9%).

- Tdap vaccination coverage increased in 2016 compared with 2015 among women who were living at or above the poverty level (50.9% vs. 42.4%).

Figure 6.

Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy among recently pregnant women who had a live birth,† by poverty status,ǁ Internet panel survey, United States, April 2016 (n=662)

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations | Sample Sizes | Previous Year

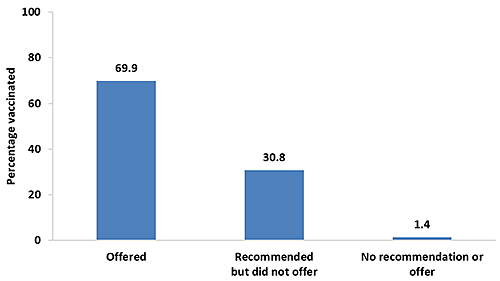

Coverage During Pregnancy by Medical Professional Recommendation and Offer

- In 2016, 63.6% of women with a recent live birth reported receiving an offer of Tdap vaccination from a doctor or other medical professional, 13.2% received a recommendation but were not offered the vaccine, and 23.2% did not receive a recommendation for Tdap vaccination.

- Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women was highest (69.9%) among women who reported that their doctor or other medical professional offered the vaccination.

- Among pregnant women who reported receiving a recommendation for but no offer of Tdap vaccination from their doctor or other medical professional, 30.8% were vaccinated.

- Only 1.4% of pregnant women who reported that they did not receive a recommendation for Tdap vaccination from their doctor or other medical professional were vaccinated.

Figure 7.

Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy among recently pregnant women who had a live birth,† by medical professional recommendation and offer of Tdap vaccination, Internet panel survey, United States, April 2016 (n=663)

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations | Sample Sizes | Previous Year

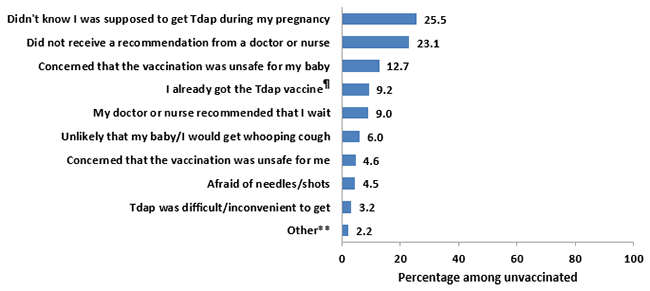

Reasons for Not Receiving Tdap Vaccination During Pregnancy

In 2016, respondents in the sample who had never received a Tdap vaccination, or who had been vaccinated but not during their most recent pregnancy, were asked to report their reasons for not receiving Tdap vaccination. They were then asked to report their one main reason for not getting a Tdap vaccination.

- Most commonly reported as a main reason for not receiving Tdap vaccination were “I didn’t know that I was supposed to get the Tdap vaccination during my most recent pregnancy” (25.5%) and “I did not receive a recommendation from a doctor, nurse, or other medical professional to get a Tdap vaccine during my pregnancy” (23.1%).

- Another commonly reported main reason was “I was concerned that the vaccination was unsafe for my baby” (12.7%).

- Potential barriers to vaccination access, such as “The Tdap vaccination was difficult or inconvenient to get” (3.2%), were reported much less frequently as reasons for not receiving Tdap vaccination.

Figure 8.

Main reason for not receiving Tdap vaccination among recently pregnant women who had a live birth and did not receive Tdap during their most recent pregnancy, Internet panel survey, United States, April 2016 (n=335)

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations | Sample Sizes | Previous Year

What Can Be Done?

Overall, estimates of Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy from the 2016 survey were higher compared with estimates from the 2015 survey. In 2016, Tdap vaccination coverage was highest among pregnant women who reported that their doctor or other medical professional offered Tdap vaccination (69.9%) compared with pregnant women who reported receiving a recommendation without an offer of vaccine (30.8%) and who did not receive a recommendation at all (1.4%). The most common reasons for not receiving a Tdap vaccination were lack of awareness about the need for Tdap vaccination during pregnancy (25.5%) and lack of a provider recommendation for Tdap vaccination during pregnancy (23.1%). Continued efforts are needed to improve Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women.

- More than half of pregnant women did not receive a Tdap vaccination during their pregnancy.

- Many unvaccinated pregnant women were not aware that they needed a Tdap vaccination during pregnancy and did not receive a recommendation for Tdap vaccination from a medical professional.

- HCP should follow guidance in the Standards for Adult Immunization Practice developed by the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) [11].

- Assess the immunization status of all pregnant patients at every visit.

- Strongly recommend Tdap vaccination to pregnant patients and provide information on the benefits of vaccination and the risks of whooping cough.

- Offer and administer Tdap vaccine to pregnant patients or give a strong referral that provides specific information on where patients can go to get the vaccine and a prescription, if needed.

- Document when Tdap vaccination has been received by pregnant patients and follow up with them about referrals to ensure that they received the vaccination.

- Information is available at:

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Frequently Asked Questions for Pregnant Women Concerning Tdap Vaccination. 2015.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Physician Script Concerning Tdap Vaccination. 2013.

- American College of Nurse-Midwives. Immunization Resources for Providers.

- Standards for Adult Immunization Practice.

- Pregnancy and Whooping Cough.

- You Can Start Protecting Your Baby from Whooping Cough Before Birth.

- Letter to Providers: Tdap and Influenza Vaccination of Pregnant Women.

- Text4baby. Texts to keep you and baby healthy.

Data Source and Methods

CDC conducted an Internet panel survey from March 29 to April 7, 2016, to assess end-of-season influenza (flu) vaccination coverage estimates among pregnant women [12]. Questions about receipt of Tdap vaccination, recommendation for and offer of Tdap vaccination from a medical professional, and reasons for not receiving Tdap vaccination were included in the survey. Women 18–49 years who were pregnant at any time since August 1, 2015, were eligible for the survey. Participants were recruited from a preexisting, national, opt-in, general-population Internet panel operated by Survey Sampling International, which provides panel members with online survey opportunities in exchange for nominal incentives. In 2016, 2,199 respondents were eligible and started the online survey. A total of 2,102 eligible respondents completed the online survey, for a cooperation rate of 95.6%. Data were weighted to reflect the age, race/ethnicity, and geographic distribution of the total U.S. population of pregnant women [13–16]. Similar methodology was used in April 2014 and April 2015 [17].

Survey respondents were asked if they ever had a Tdap vaccination and, if so, whether they received their most recent vaccination before, during, or after their most recent pregnancy. Pregnancy status questions included whether respondents were currently pregnant at the time of the survey or had been pregnant any time since August 1, 2015. Recently pregnant women were asked if they had a live birth. The current analysis included only recently pregnant women who had a live birth. Women who reported receiving vaccination during their most recent pregnancy were counted as vaccinated during pregnancy, while women who reported never being vaccinated or being vaccinated before or after their most recent pregnancy were counted as not vaccinated during pregnancy. In the 2016 survey, 100 out of 763 women with a live birth (13.1%) were not included in the analysis because they did not know if they had ever received a Tdap vaccination or did not know if the Tdap vaccination was received during their pregnancy, leaving a final analytic sample of 663. Respondents who had at least one medical visit since the preceding July were asked if any doctor or other medical professional had recommended or offered Tdap vaccination during their most recent pregnancy. Respondents who had not received Tdap vaccination during their most recent pregnancy were asked about reasons why they were not vaccinated.

Weighted analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2) survey procedures. Because the opt-in Internet panel sample was based on those who initially self-selected for participation in the panel rather than a random probability sample, statistical measures, such as calculation of confidence intervals and tests of differences, were not performed [18]. A change between years or a difference between groups was noted when there was a difference in estimates of at least 5 percentage points.

Sample Demographics

- A total of 663 women who were pregnant any time from August 1, 2015, until the survey date in 2016 were included in the analysis. Table 1 shows the frequency of women in each demographic subgroup in the 2016 survey.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of recently pregnant women who had a live birth,† United States, Internet panel survey, April 2016

| Characteristics | unweighted n |

weighted % |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 663 | 100.0 | ||

| Age group | ||||

| 18-24 years | 161 | 29.0 | ||

| 25-34 years | 399 | 55.3 | ||

| 35-49 years | 103 | 15.7 | ||

| Race/ethnicity‡ | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 410 | 59.3 | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 92 | 16.9 | ||

| Hispanic | 110 | 16.9 | ||

| Non-Hispanic other | 51 | 6.9 | ||

| Education | ||||

| High school degree or less | 143 | 22.8 | ||

| Some college | 215 | 33.0 | ||

| College degree | 231 | 33.8 | ||

| More than a college degree | 74 | 10.4 | ||

| Insurance status§ | ||||

| Private/military insurance only | 361 | 53.7 | ||

| Any public insurance | 287 | 46.3 | ||

| Living in poverty|| | ||||

| At or above poverty | 497 | 73.5 | ||

| Below poverty | 165 | 26.5 | ||

Footnotes | Data Source and Methods | Limitations

Limitations

The findings in the report are subject to several limitations.

- The sample was not necessarily representative of all pregnant women in the United States because the survey was conducted among a smaller group of volunteers who were already enrolled in a preexisting, national, opt-in, general-population Internet panel rather than a randomly selected sample.

- Some bias might remain after weighting adjustments, given the exclusion of women with no Internet access and the self-selection processes for entry into the panel and participation in the survey. Estimates might be biased if the selection processes for entry into the Internet panel and a woman’s decision to participate in this particular survey were related to receipt of vaccination.

- All results are based on self-report and not validated by medical record review. However, our vaccination coverage estimates are similar to a recently published estimate based on provider-reported data from the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) sites (42.1%) [19].

- Formal statistics were not used to determine differences in vaccination coverage estimates between groups and seasons.

- Some subgroups had small sample sizes.

- Estimates could be biased due to the exclusion of ~13% of respondents who did not know their vaccination status. Sensitivity analysis showed that actual vaccination could have ranged from 43.0% to 55.0% in 2016.

Despite these limitations, Internet panel surveys are considered a useful assessment tool for timely evaluation of Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy.

AUTHORS: Katherine E. Kahn, MPH1; Carla L. Black, PhD2; Helen Ding, MD, MSPH3; Amy Parker Fiebelkorn, MSN, MPH2; Jennifer L. Liang, DVM, MPVM4; Indu B. Ahluwalia, PhD5; Denise D’Angelo, MPH6; Sarah W. Ball, ScD7; Rebecca Fink, MPH7; Rebecca Devlin, MA8; Stacie M. Greby, DVM, MPH2

1Leidos, Atlanta, GA

2Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC

3CFD Research Corporation, Huntsville, AL

4Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC

5Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC

6Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC

7Abt Associates Inc., Cambridge, MA

8Abt SRBI, New York, NY

Related Links

- AdultVaxView

- Frequently Asked Questions for Patients Concerning Tdap Vaccination

- Pregnant? Get Tdap in Your Third Trimester

- Standards for Adult Immunization Practice

- Updated Recommendations for Use of Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine (Tdap) in Pregnant Women — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012

- Text4Baby

References/Resources

- CDC. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged <12 months — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR 2011;60(41):1424-26. Accessed 1/11/2016.

- Kretsinger K, Broder KR, Cortese MM, et al. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adults: Use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine. MMWR 2006;55(RR17):1-33. Accessed 1/11/2016.

- CDC. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR 2013;62(7):131-5. Accessed 1/4/2016.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Update on immunization and pregnancy: Tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccination. Committee Opinion No. 566. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1411–4. Accessed 1/11/2016.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Immunization for women. 2015. Accessed 1/4/2016.

- Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: An observational study. Lancet 2014;384(9953):1521–28.

- CDC. You can start protecting your baby from whooping cough before birth. 2015. Accessed 1/4/2016.

- Dabrera G, Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, et al. A case-control study to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in protecting newborn infants in England and Wales, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60(3):333-7.

- Winter K, Nickell S, Powell M, Harriman K. Effectiveness of prenatal versus postpartum Tdap vaccination in preventing infant pertussis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 13.

- Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices. ACIP meeting information. 2016. Accessed 10/17/2016.

- National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: Standards for adult immunization practice. Public Health Rep 2014;129:115-23.

- Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, et al. Flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women — United States, 2015–16 influenza season. 2016. Accessed 10/14/2016.

- Curtin SC, Abma JC, Kost K. 2010 pregnancy rates among U.S. women. NCHS Health E-Stat. 2015. Accessed 10/27/2016.

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Final data for 2014. National vital statistics reports; vol 64 no 12. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. Accessed 10/27/2016.

- Jones, RK, Jerman, J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2011. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2014;46(1):3–14. Accessed 2/8/2016.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: Final data for 2011. National vital statistics reports; vol 62 no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2013. Accessed 2/8/2016.

- Kahn KE, Black CL, Ding H, et al. Pregnant women and Tdap vaccination, Internet panel surveys, United States, April 2014 and April 2015. 2016. Accessed 10/31/2016.

- Baker R, Brick JM, Bates NA, et al. Summary report of the AAPOR Task Force on non-probability sampling. J Surv Stat Methodol 2013;1:90–143.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind HS, et al. Maternal Tdap vaccination: Coverage and acute safety outcomes in the vaccine safety datalink, 2007–2013. Vaccine 2016;34(7):968-73.

Footnotes

* Infants are recommended to receive their first vaccination against whooping cough at 2 months of age [1;2].

† Respondents were asked if they were currently pregnant or had been pregnant any time since August 1, 2015. Women were included in the analysis if they were recently pregnant (since August 1), had delivered a live birth, and knew their Tdap vaccination status and timing of their most recent vaccination.

‡ Race/ethnicity was self-reported. Women identified as Hispanic might be of any race.

Women categorized as white, black, or other race were identified as non-Hispanic. The “other” race category included Asians, American Indians or Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders, and women who selected “other” or multiple races.

§ Women considered to have any public insurance selected at least one of the following when asked what kind of medical insurance they had: Medicaid, Medicare, Indian Health Service, state sponsored medical plan, or other government plan. Women considered to have private/military insurance selected private medical insurance and/or military medical insurance and did not select any type of public insurance. Due to small numbers (n<30), Tdap vaccination coverage was not calculated for respondents who reported that they had no insurance of any type.

|| Poverty status was defined based on the reported number of people and children living in the household and annual household income, according to the U.S. Census poverty thresholds.

¶ Main reason for not getting Tdap vaccination during pregnancy was coded as “I already got the Tdap vaccine (during a previous pregnancy or at another time).”

** “Other” main reason for not receiving Tdap vaccination during pregnancy included “My pregnancy ended before I could get a vaccination,” “The Tdap vaccination costs too much or is not covered by my insurance,” and “Any other reason.”

- Page last reviewed: September 19, 2016

- Page last updated: September 19, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir