Transcript

Download Slides

Nomi Levy-Carrick, MD, MPhil: Hello. I am Nomi Levy-Carrick, Mental Health Director at the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, World Trade Center Environmental Health Center, and assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at NYU School of Medicine in New York City. Welcome to this program titled "Airway, Digestive, and Mental Health Comorbidities in the World Trade Center Responders and Survivors."

Joining me today are Michael Crane, director of the World Trade Center Health Program Clinical Center and assistant professor of preventive medicine at Selikoff Centers for Occupational Health, both at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City; David Prezant, Chief Medical Officer, New York City Fire Department (FDNY) Special Advisor to the Fire Commissioner for Health Policy and codirector of the World Trade Center Health Program of the FDNY; and Joan Reibman, Medical Director of New York City's Health and Hospitals Cooperation, World Trade Center Environmental Health Center, and professor in the departments of medicine and environmental medicine at the NYU School of Medicine in New York. Welcome.

The goals of this program are 3-fold: to identify the groups of individuals effected by the 9/11 terrorist attacks and environmental disaster and their range of exposures, to describe acute and longer-term aerodigestive and mental health impacts on populations exposed to the World Trade Center disaster, and to describe the benefits of a patient-centered multidisciplinary program in managing 9/11 exposure-related medical and mental health comorbidities.

Before we begin our discussion, please take a moment to test your knowledge on this topic by answering a few questions. You will have another chance to answer these questions at the end of the activity to see what you have learned.

Dr. Crane, why don't we start, by describing the populations with potential World Trade Center dust exposure?

Michael Crane, MD: Thank you Nomi. Sure. We will talk about our rescue and recovery workers, our first responders, policemen, our firemen, EMTs, folks who did recovery work, construction workers, volunteers, other personnel who worked on that "pile," who did demolition, and a removal of materials. We'll also include the cleanup workers who cleaned up around the buildings and the environment in the community.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: Dr. Reibman, could you talk about the community population?

Joan Reibman, MD: Certainly. There were many community members exposed. Under the Zadroga Act, they are now called survivors. These community members include people in the World Trade Center towers who had to evacuate, people who worked in the nearby area, and/or people who were street vendors, as well as local residents who lived in the surrounding areas. There were also many students and teachers in the surrounding area, as there is a nursery school, an elementary school, middle and high schools, and colleges nearby. And then there are the people who just came to see the World Trade Center towers on that day.

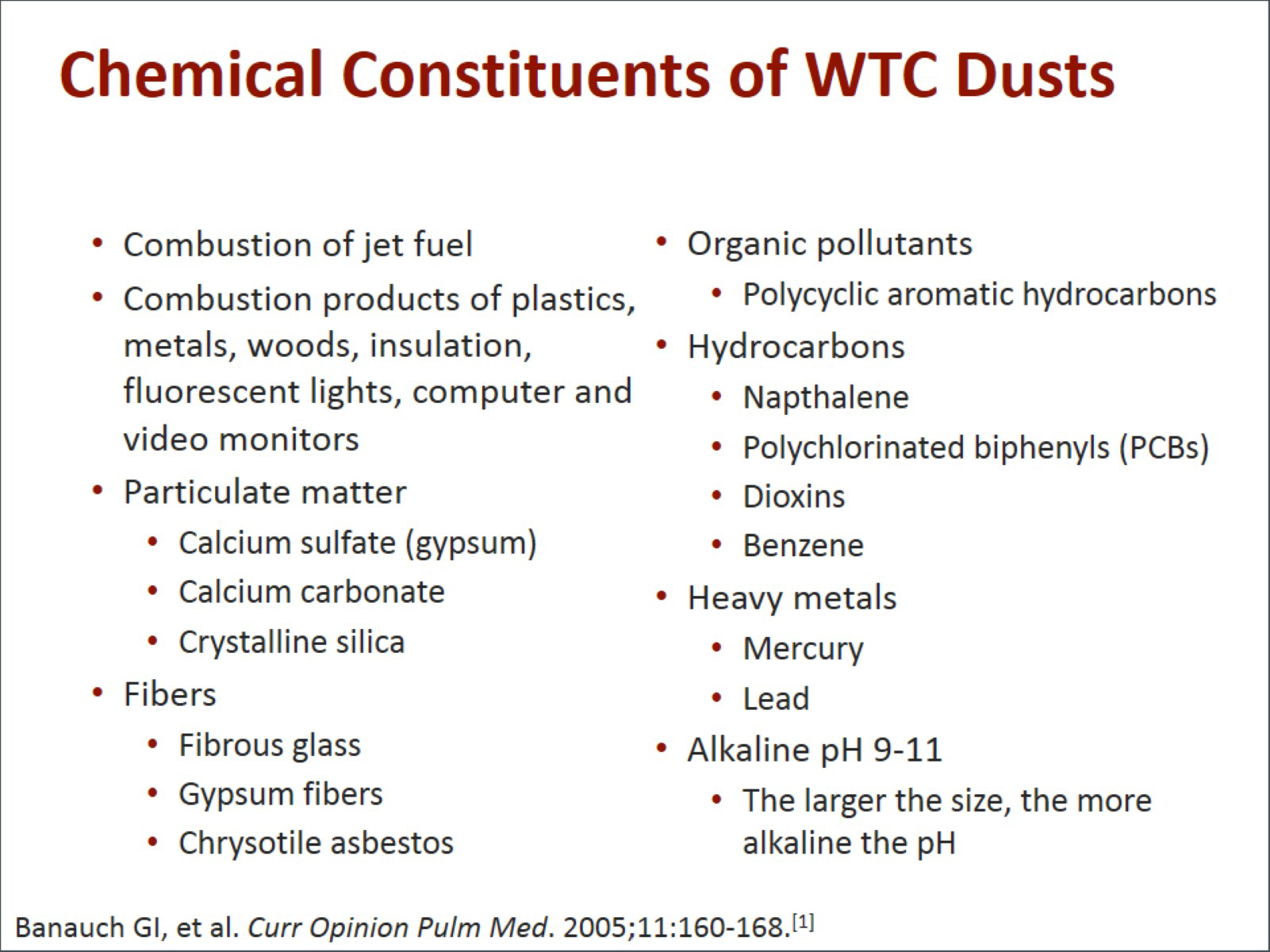

Dr. Levy-Carrick: Dr. Prezant, could you talk about some of the chemical constituents of the World Trade Center dust?

David Prezant, MD: First off, 2 airplanes collided, so there was combustion of jet fuel. There were the combustion products from the buildings themselves: the plastics, the metals, wood, insulation, fluorescent lights, computers, video monitors, and then all the particulate matter that resulted from that, which was heavily laden with calcium sulfate, a component of gypsum and Fibrowood, calcium carbonate, crystalline silicates, fibrous glass, gypsum fibers, and chrysotile asbestos. With all that burning, you had organic pollutants, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, PCBs, dioxin, benzene, heavy metals, lead, and mercury. All of these particulates, especially the larger ones, had a very high alkaline pH, which added to their inflammatory properties.

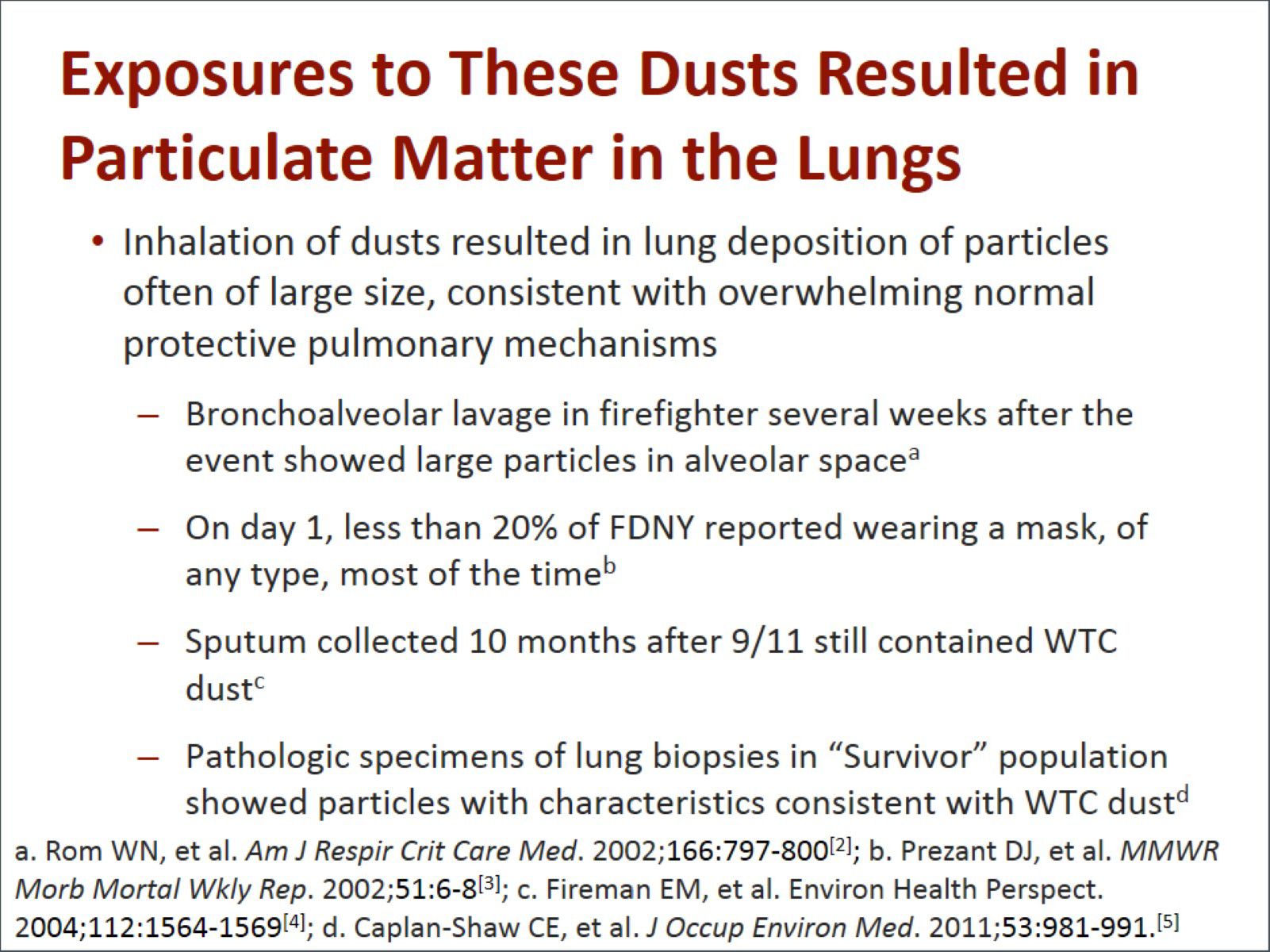

The inhalation of these dusts, gases, and fumes resulted in lung deposition of particles that were often large in size, high in pH, very irregular in shape. All of this results in chronic inflammation. We know that the dust and particles got down into the lungs. Several weeks after the event, we did bronchoalveolar lavage in a firefighter who was suffering from severe lung disease. While assessing and treating him, we inserted the scope, washed his lungs out, and saw these particles in there. In patients less affected, 10 months later we looked at firefighters. We asked them to cough up some sputum, and lo and behold, we found particles consistent with World Trade Center dust. Other centers have done biopsy specimens of the lung and have found similar particles in both survivors and responders.

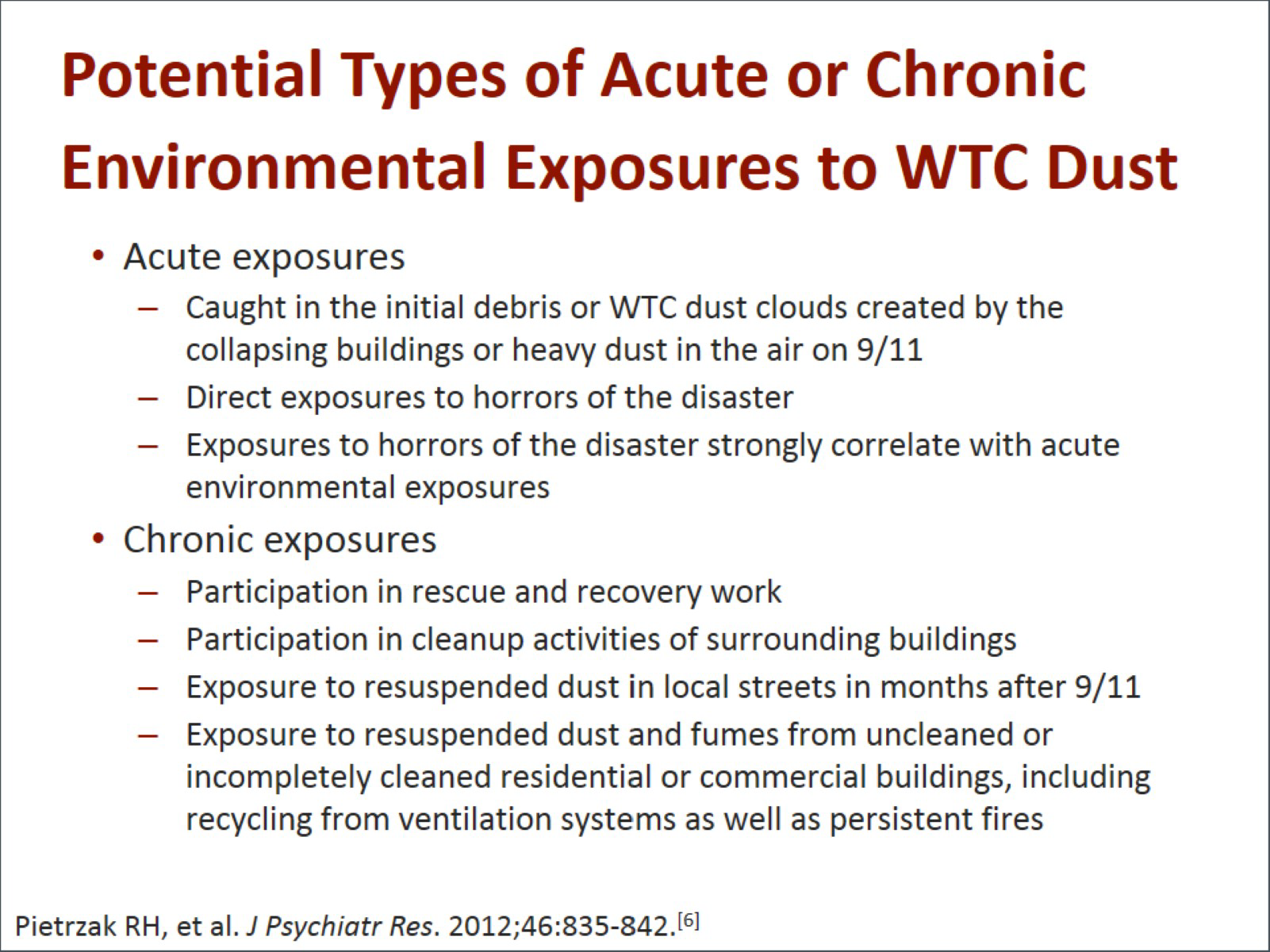

Dr. Reibman: We now understand that there are in fact both acute and chronic environmental exposures to the dust and to the events that occurred on 9/11. Many people had acute exposure after they were caught in the initial dust from the debris or in the dust clouds as the buildings collapsed. We know that people also had other acute exposures such as exposures to many of the horrors of the disaster, and that those exposures strongly correlate with acute and environmental exposures.

We also think that there are chronic exposures that occurred in people who were involved in long-term participation and rescue and recovery work, people who were involved in long-term cleanup activities in the surrounding buildings, people exposed to resuspended dust. So workers, local workers, and residents were exposed to resuspended dust in the nearby streets in the months after 9/11. Many of the local commercial spaces and residential buildings were not completely cleaned or there was resuspension of the material within those buildings, recycling from the ventilation systems, as well as persistent fumes from the fires.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: How did this end up manifesting?

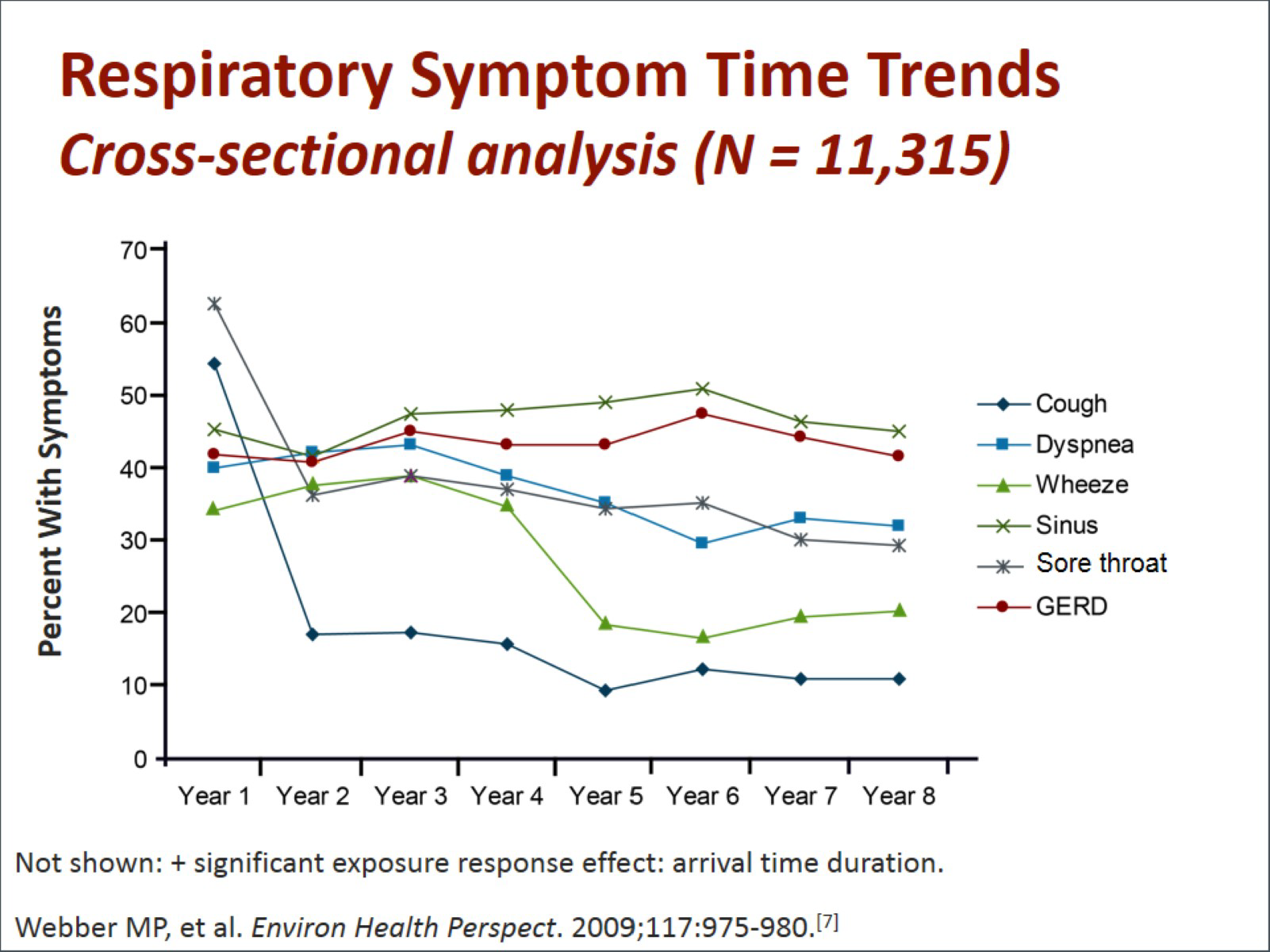

Dr. Crane: The respiratory symptoms were present that day. Everybody had a cough. Everybody had trouble breathing, a sore throat, throat pain, and a runny nose. So as of day 1, 100% of the exposed population had these symptoms. We looked at this over time, and the 2 symptoms most prevalent early on -- cough and sore throat -- actually diminished over time. Now, in 2015, you have about 10% to 20% of people with chronic cough and chronic sore throats whose symptoms have persisted unchanged. In about 40% of our firefighters there has been shortness of breath, chest tightness, the inability to take a deep breath, and intermittent wheezing. These symptoms were associated with a decline in lung function.

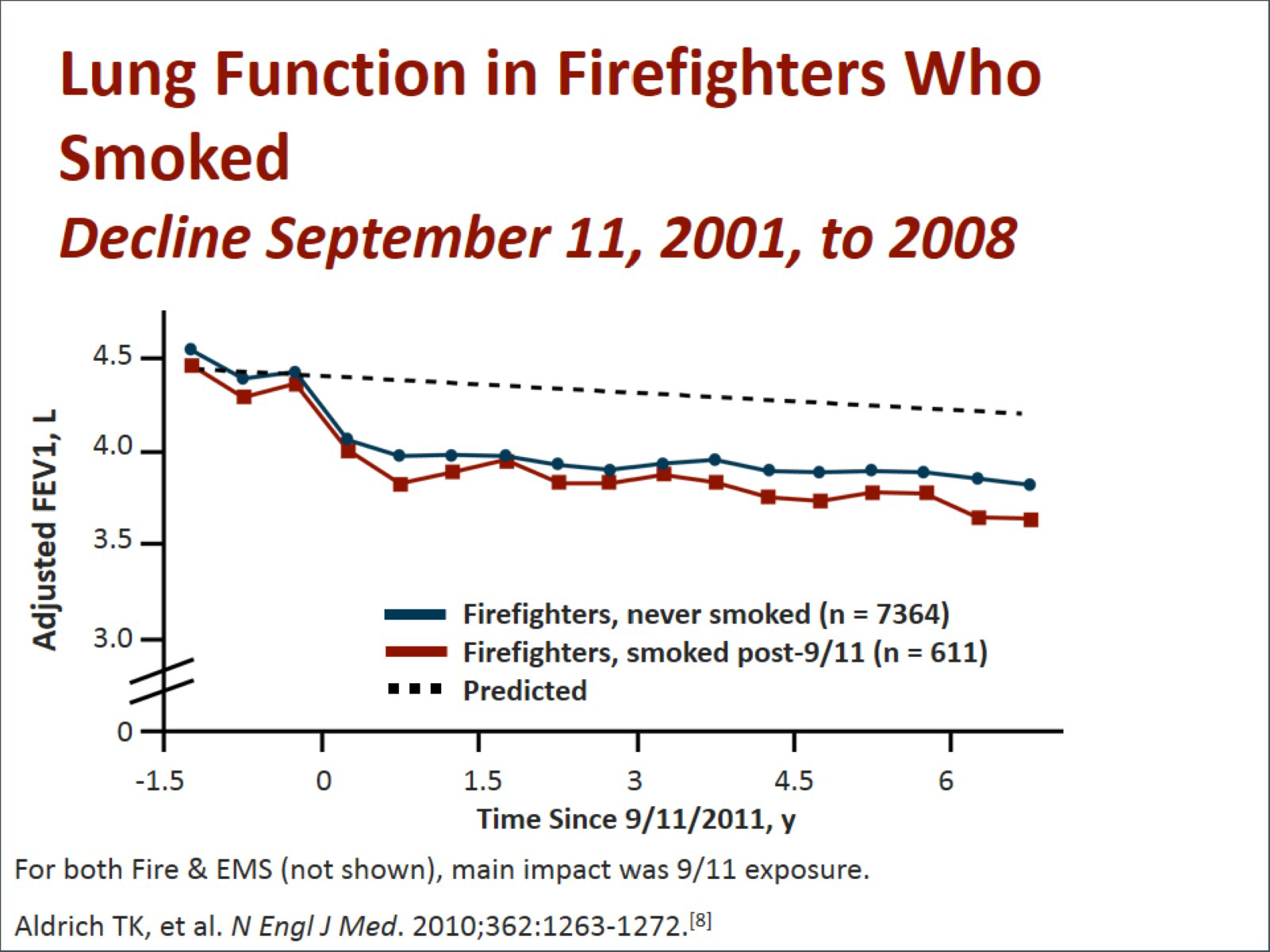

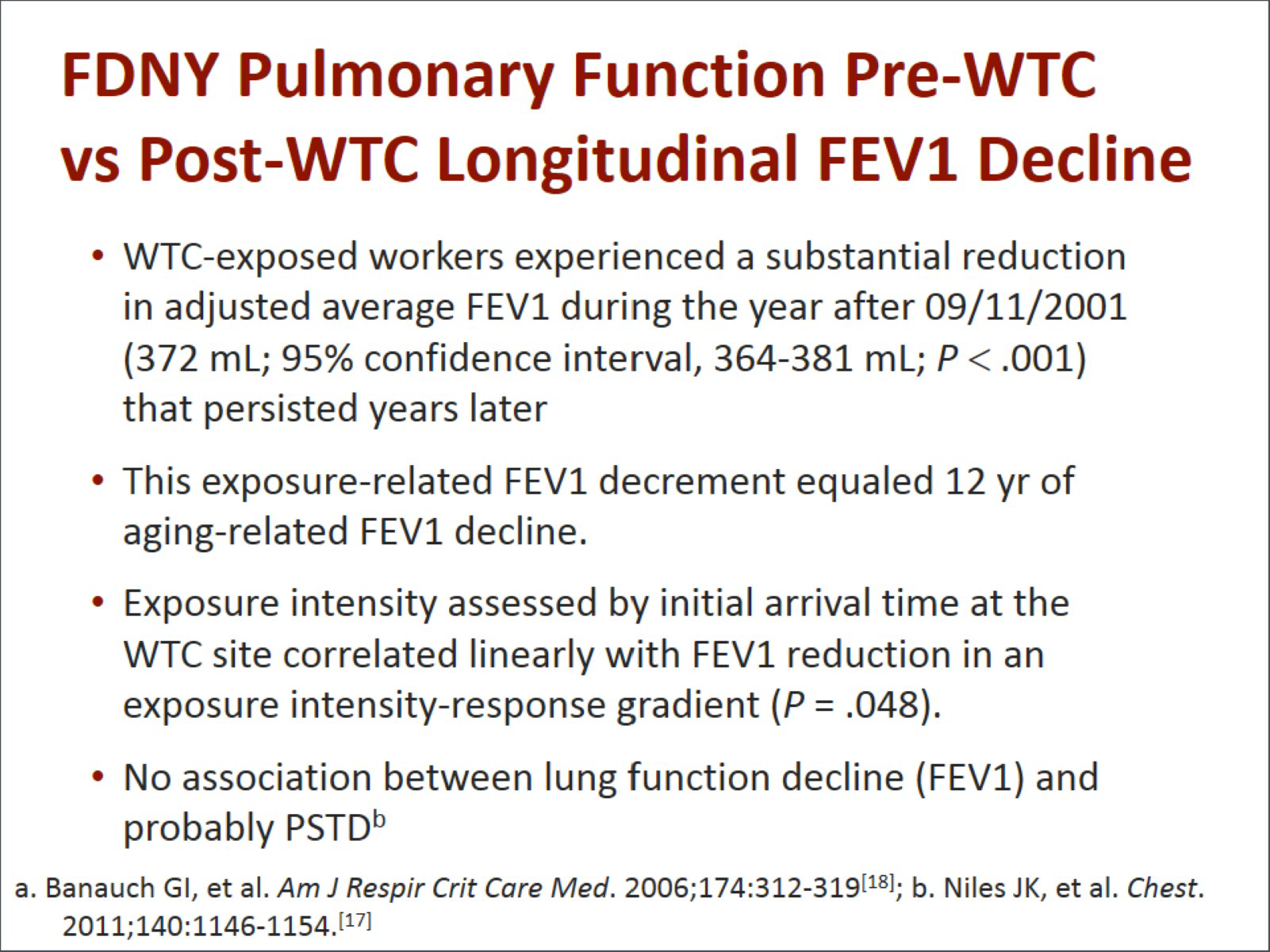

The New York City Fire Department (FDNY) measured lung function even before 9/11 as part of our annual medical exam because firefighters are always exposed to hazards. In those firefighters, we found that their decline in lung function on an annual basis was what you would expect from normal males. It would reduce by about 30 mL per year. But in the first 6 to 12 months after 9/11, lung function declined by 12 times that amount, by an average of about 370 mL -- almost the equivalent of 2 cans of soda in terms of air loss. In people with severe symptoms it was even worse. The other thing we found was that this was a chronic problem because it persisted. Their lung function did not return to normal, as you can see on this slide. People have also said, "Well, this is only a problem with cigarette smokers." On this slide blue is for people that never smoked, and red is for smokers. You can see that there is very little difference between those who did and did not smoke. This was really a decline in lung function that was persistent and that was really only dependent on 9/11 exposure.

Dr. Reibman: The firefighters are a valuable group of people for us as we try to understand the impact of the World Trade Center environmental exposures, but there are many other populations involved that are much more difficult to study. We do know, however, that in a group of community members who lived in the area, they had in fact new-onset respiratory symptoms that were different from those in a controlled group. For example, there was an increase in the percentage of people who complained of new-onset and persistent cough, chest tightness, shortness of breath, exertional dyspnea, and wheezing. That was very different from a comparable group who lived in a very different area without the exposure. So we see that there were other populations who clearly had acute and chronic exposures and symptoms.

The people who have come to the World Trade Center Environmental Health Center are self-referred. But they self-refer for the same symptoms that we are hearing about in the responders and in the firefighters. These include lower respiratory symptoms such as cough, wheeze, dyspnea on exertion, chest tightness, sinus and nasal symptoms, as well as gastric esophageal symptoms.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: Dr. Crane, can you tell us a little more about the broader population?

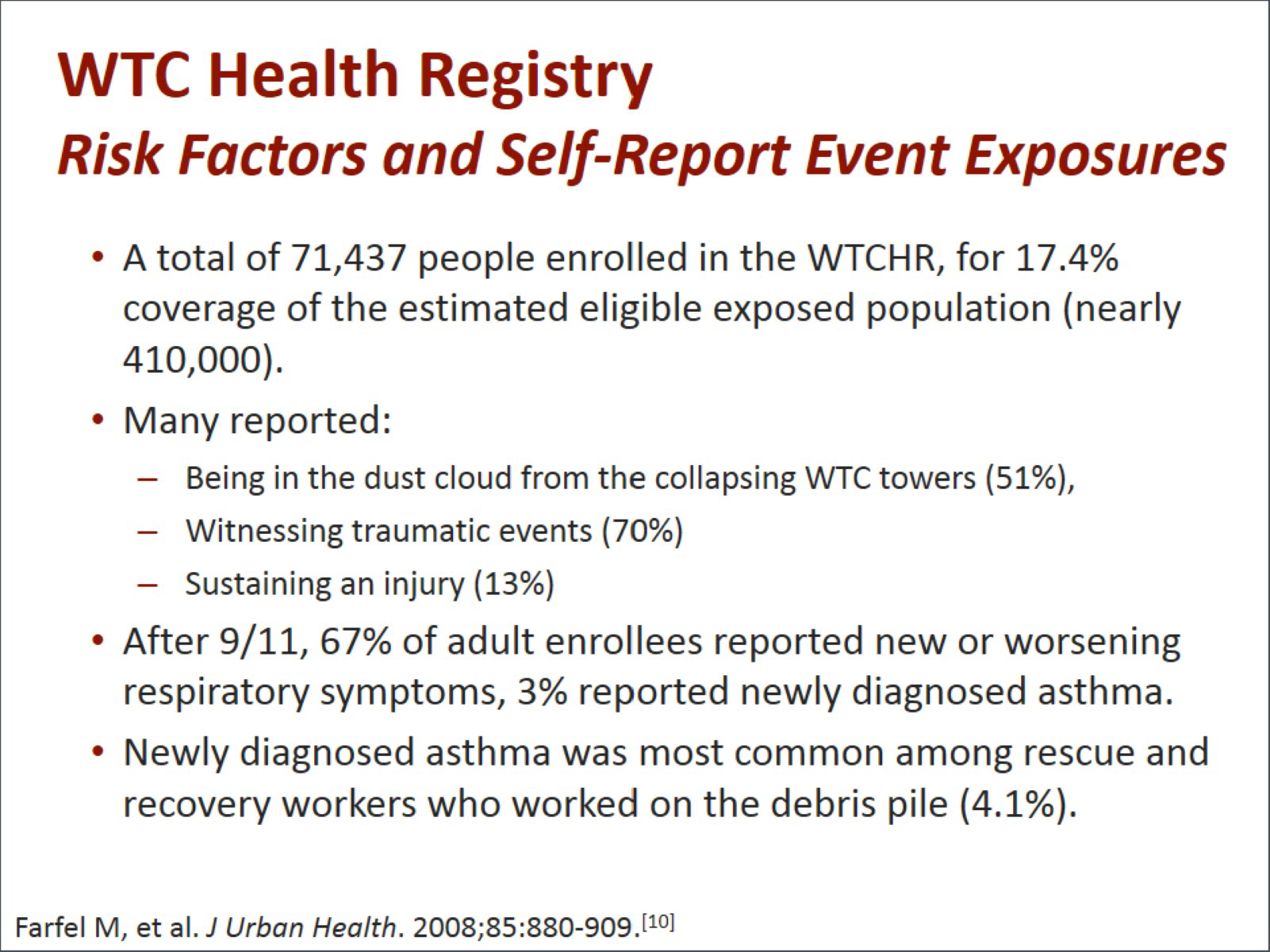

Dr. Crane: A very good example of the broader population can be seen in the studies of the World Trade Center Registry, which is a combined study of both community members and workers. They studied 70,000 people over time. At least half of them (51%) reported actually being in the dust cloud, 70% witnessed traumatic events, and 13% of them sustained an injury. After 9/11, more than two-thirds of the adults reported new or worsening respiratory symptoms. Newly diagnosed asthma was one of the most common symptoms reported.

Common physical illnesses and complaints found included respiratory problems, asthma or other asthma like symptoms, shortness of breath, chronic cough, upper respiratory symptoms of chronic rhinitis or sinusitis, obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease or heartburn, musculoskeletal syndromes, as well as a complex and difficult condition to diagnose condition called sarcoidosis, and, unfortunately, cancer.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: There are also common mental health disorders that we are seeing in this postdisaster setting. We see posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but also anxiety; depression; misuse of a variety of substances, especially tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis; and adjustment disorders. All are chronic medical illnesses that you have just been describing. There are symptoms common to all of the conditions that really cut across them: insomnia, irritability, attention problems, and concentration issues. These can have a major effect on functioning.

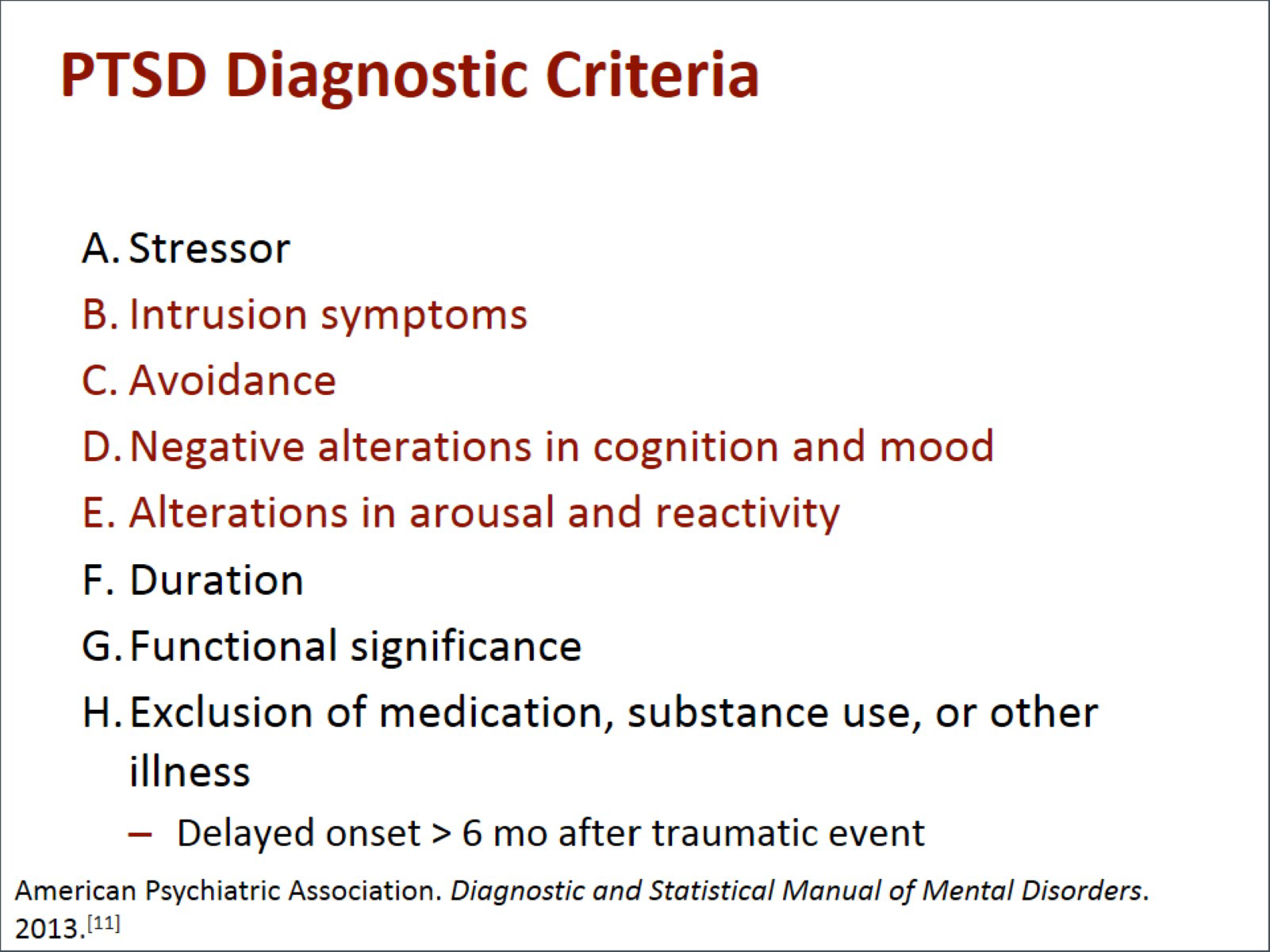

One of the things about PTSD that is quite relevant to this population is that unlike anxiety or depression, it has a somewhat unique combination of symptoms: hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, memories, and flashbacks, but also emotional numbing and avoidance. That combination of symptoms can sometimes be very debilitating in a variety of different ways and affects the way people engage their medical treatment. It is not just having memories of 9/11 that we are talking about. It is actually being functionally impaired by the intensity and frequency of those symptoms.

We thought it would be helpful to learn about these 9/11-related issues by studying a few cases. Dr. Reibman is going to tell us about the first case.

Dr. Reibman: This is the case of a woman who is quite representative of many of the patients we see in our program. She was working in the towers themselves on 9/11. She heard a commotion, but it was not clear what to do. Eventually she became concerned. Although she was told to stay put, she decided to make her way down the tower and climbed all the way down the stairs with great difficulty. When she got out, she had gone a few blocks when the towers collapsed.

She was caught in the massive dust cloud. She could not see. She fell down. She was terrified and thought that she was going to die. Luckily, somebody pulled her up, assisted her, and then eventually helped her walk across the Brooklyn Bridge and all the way home.

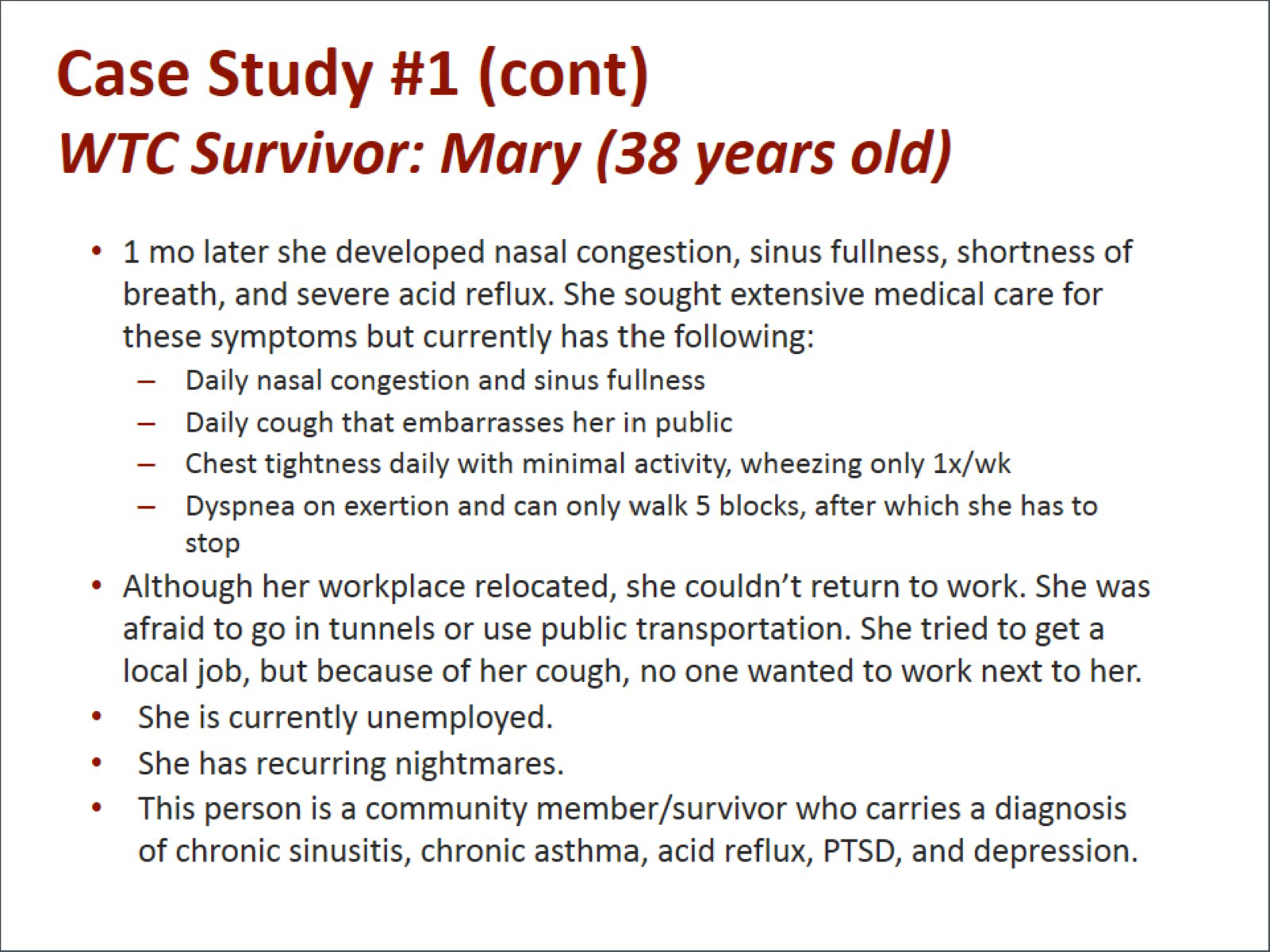

A month later, she started to complain of nasal congestion, sinus fullness, shortness of breath, and severe acid reflux, and she sought medical care. In fact, after many years of seeking treatment, she continues to have daily nasal congestion and sinus fullness and daily coughing that embarrasses her in public. She has chest tightness every single day and can do very few activities because she becomes wheezy and short of breath.

Although her workplace relocated, as they could no longer be in the towers, she could not return to work. She was afraid to go into tunnels, and she was afraid to use public transportation. She tried to get a job in her local area, but she could not maintain her position because her coughing was so irritating to everyone around her that she could not continue to work. She is currently unemployed. She also has recurring nightmares. This is a community member or a survivor who carries a diagnosis of chronic sinusitis, chronic asthma, acid reflux, PTSD, and depression, all of which were new to her after 9/11.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: This case profoundly demonstrates the interplay between the physical and mental health symptoms that we have been seeing in our population. The respiratory symptoms themselves can cause psychological distress, and they can function as triggers or reminders of the traumatic event itself. A lot of the work that we do is trying to sort out their perceptions or misperceptions of asthma vs panic, anxiety symptoms of deconditioning, fatigue, and depressive symptoms. Survivor guilt can sometimes play a role in delays to treatment both for medical and for mental health concerns, and it also impacts people's adherence to treatment as well. They lack the ability to reengage, and they feel they are not entitled to have joy again. A lot of our work is really about making sure that we are not calling one thing another.

Dr. Crane: There are some common factors associated with this comorbidity and the symptoms of PTSD and respiratory concerns that are common to both responders and survivors. There was intense exposure to the dust cloud. There were work exposure measures. There was exposure to the dust with the survivors in their own homes when folks in the community went back to their workplaces. There is a lack of social support. That is very important. Were they depressed pre-9/11? What is their education level? The net effect of all of this is that more than 40% of these folks experience a very significant disability.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: This co-occurrence of lower respiratory symptoms and PTSD is seen in all of the impacted populations, but there is variability among the specific populations. One of the things we think about is what were their acute exposure stressors? We compare that to some of the longer-term ones.

Three exposures that have really clearly been associated with a greater PTSD risk in both the responders and civilians was a physical injury on 9/11, witnessing the horrors of the day, and the loss of a loved one and/or colleagues at that time.

Longer term, there is a broader range of stressors that have a psychological impact. Development of a chronic or disabling medical illness is a very important stressor. Continuous exposure to toxins or images of the disaster remains a very relevant variable, but so does loss of a home, job, or income. A lot of social supports revolve around all of these factors. We have come to appreciate the significant role all of these triggers play in how people ended up managing in the years following 9/11.

Even now, there are current events that come up that can retrigger a lot of symptoms, often taking people by surprise. We had Hurricane Sandy in the city a few years ago, where people really did have direct exposures. Even things in the news that are less direct -- the Boston Marathon bombings, other things that have been going on in the world -- can really trigger someone or prompt them to come to seek treatment with us. We must be sensitive to why that might be, and why it is happening. This becomes a source of reassurance and helps people engage in both their medical and mental health treatment.

Dr. Reibman: When we think about treatment for people like this patient, we really understand that they need a full medical evaluation, including an extensive diagnostic evaluation, to make sure a diagnosis is correct. If we have a diagnosis, there is an extensive long-term treatment for this diagnosis based on guidelines; however, they also need comprehensive mental health evaluations. They really need a medical and a mental health interdisciplinary approach, and the treatment has to combine both aspects. On top of that, we have to understand that many of these patients have huge social stressors. For example, this woman no longer has a job. They need support for a lot of these stressors. We also have to understand that this is chronic: These patients need chronic disease management. That is what we do at the Clinical Center of Excellence and what we hope that we can continue to do to be able to help these patients.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: Let us change tack. For this second case, we wanted to discuss a member of the FDNY.

Dr. Prezant: This is a fire lieutenant named Brian. He is approximately 40 years old. On 9/11 he is commanding 5 firefighters. They are in the towers. He sends 3 to the left, 2 to the right as they enter. During the collapse, he and the 2 that he sent to the right are blown free. The 3 that he sent to the left die, and their bodies are never recovered. That haunts him.

He digs himself out of the rubble that day. He goes to the emergency department, where he is complaining of cough, nasal congestion, sore throat, and ringing in his ears from the explosion. Before he can get any real treatment, he signs himself out of the hospital to try to get back to the site to find out what happened to his guys, what happened to friends, other firefighters that he either trained with or has worked with over the past 20 years. For 2 weeks, he is down there nearly every day. He searches but never finds anyone, which makes things even worse.

The exposures there are causing coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath; the shortness of breath is typical of the World Trade Center symptoms. He is short of breath when he exerts himself physically, but he also feels that he can never catch a deep breath. He improves a little bit after a brief vacation over the next 10 months. He continues to go down to the site, searching yet never finding.

One night he awakens, and he is screaming. He is sweating. His wife does not know what is going on. She says it is finally time for you to go see a doctor. He comes to our World Trade Center Health Program and gets a full evaluation. We are able to compare his breathing test to the ones he had before 9/11. We see a tremendous decline, but he never tells us about his nightmares because he is embarrassed. He has always been a giant: He is not supposed to discuss these things, so he just tells us about his cough.

Two years later, after some treatment for these physical conditions, his cough is a little bit better and he hears through the grapevine that the body parts of one of his men have been found and identified by the Chief Medical Examiner. A funeral ceremony is planned. He does not know whether he should go or not go. It precipitates his nightmares again. His mental health symptoms get worse and binge drinking also occurs. Fights with his wife makes matters even worse.

When he is short of breath, he uses his inhalers. His wife turns to him and says, "It is embarrassing to us. Why are you continuing to use your inhaler?" He says, "I have to use my inhaler." His wife loves him, but they are falling apart. Once he admits to these things, once we realize these things, then we are able to give him combined physical and mental health therapy, which has kept his family together.

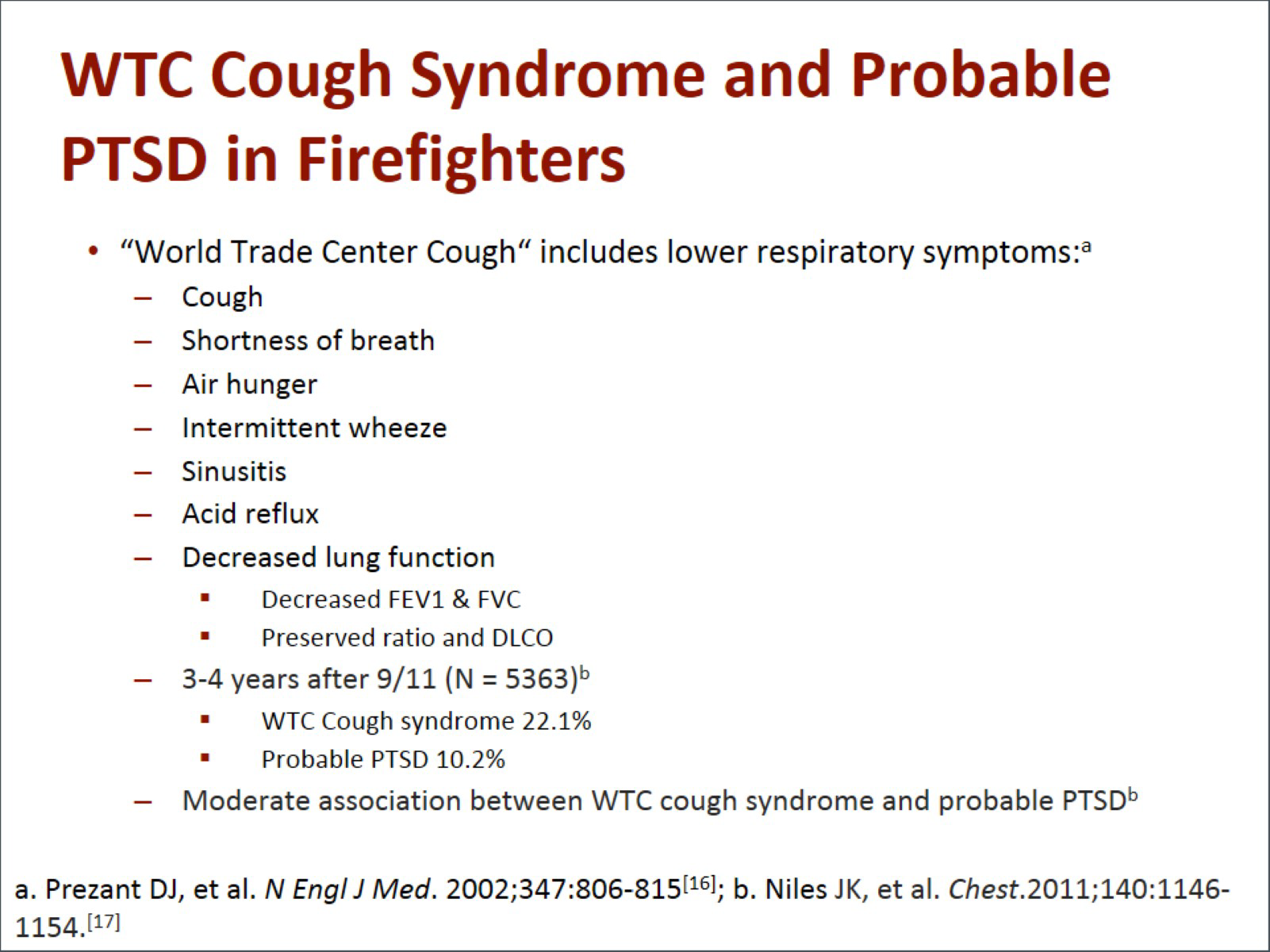

World Trade Center cough syndrome has all of the upper and lower respiratory and GERD symptoms that we have talked about already. In many patients, it is a substantial decline in their lung function. Interestingly, it is mostly obstructive airway disease; we have not seen a lot of interstitial lung disease. However, as Dr. Crane mentioned, we have seen a good amount of sarcoidosis. We have also seen posttraumatic stress disorder, which in our population affects about 25% of the people who were there during the morning of 9/11, but about 10% of the entire group. It has been evolving over time to be depression as well as PTSD.

People talk about this association between the physical health symptoms and the mental health symptoms, and there clearly is one. What we should not forget is that both of these diseases, in the physical health and mental health realms, are real, and there are objective findings for them.

In physical health, we have seen this decline in lung function, but interestingly, the decline in lung function does not associate with the PTSD symptoms. The symptoms of lung disease do, but not the decline of lung function. What that tells us is these are 2 separate diseases in many of these patients, but they are interwoven so that one makes the other worse symptomatically and more difficult to manage.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: It is interesting. One of the things you mentioned is that sometimes the family is embarrassed about him using the pump. One of the things that we see more often is that the patient is too embarrassed to use the pump. They start avoiding all these social situations precisely because they do not want to have this moment where they actually need to use it and they are too embarrassed to do so, so they just start isolating all together.

Dr. Prezant: We see the same thing. Firefighters normally can climb 6 to 10 flights of stairs carrying a hundred pounds of equipment on their back, and now with 1 flight of stairs with no equipment, they are short of breath and sucking on an inhaler.

Dr. Reibman: The other thing that we see is community members not going for treatment due to the concept of survivor guilt. People who survived when their workmates did not feel that they failed by not rescuing them. Recovery workers therefore feel that they are not entitled to services, when in fact, they were all exposed, and all had similar symptoms.

Dr. Crane: "Someone else needs it more than I do."

Dr. Levy-Carrick: That is a recurring statement as people come in. They are going through that process even when you are offering treatment. There is an ambivalence that can come from so many different places.

Dr. Crane: "I should not be here, doc, give it to somebody else."

Dr. Prezant: Despite how ill they are, every one of them would have done it again, all over again.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: How can we best help Brian?

Dr. Prezant: First off, we have to diagnose this. We need a screening. We need to do monitoring. We find abnormalities when we really engage the patient by asking him questions repeatedly, not accepting the first answer, but digging down. Once we have the diagnoses then we have to offer him hope because there truly is hope that these treatments can work. Treatment for asthma and treatment for GERD can work incredibly well. Treatment for sinuses works well, as can mental health treatment. We know we can make a change in the way that people live and the way that they interact with their family members. It is a comprehensive diagnostic plan and a comprehensive treatment plan.

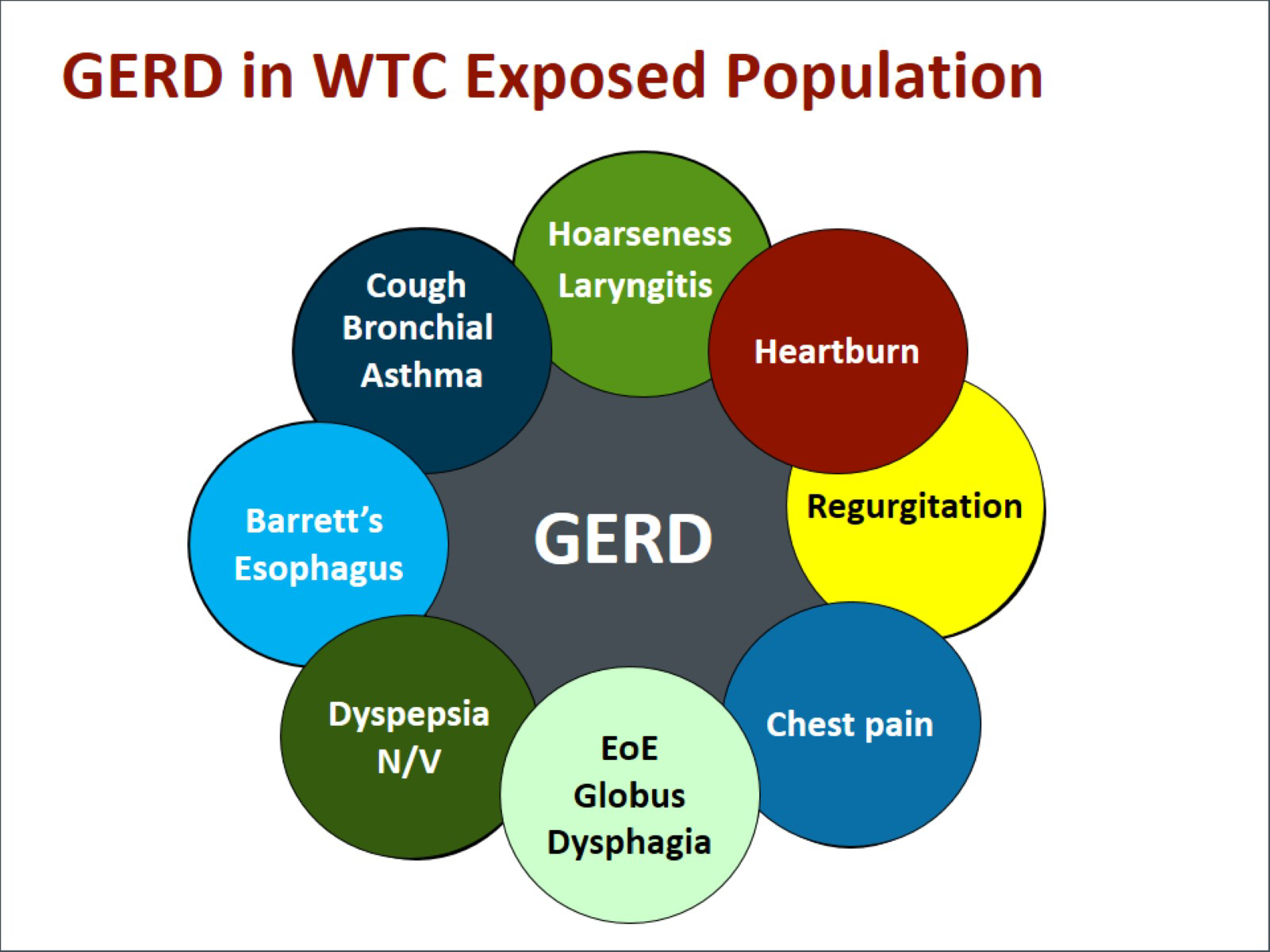

During this entire process, we have to keep our eyes open, not just for diseases that we know that they might have, but for diseases that might occur. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a perfect example of this. No one thought that acid reflux would be part of this World Trade Center Cough syndrome. Cough, lower airway, upper airway makes sense, but what we found and what has been shown in all the cohorts is tremendous acid reflux. Is it precipitated by ingesting the same inflammatory particles, by the stress, and by some interaction between the respiratory airways and the esophagus that we do not fully understand?

It could be all of the above, but GERD has serious implications. It is not just somebody with a stomachache. We know from other populations that acid reflux worsens cough. It worsens asthma. It worsens sinus disease because the vapors come up and continually inflame the upper airway. It can cause chest pain, which some patients misdiagnose and are worried that they are having a heart attack. It can be the beginning of an inflammatory cycle that may lead to esophageal cancer. Barrett's esophagitis can be a problem from GERD: If left untreated, it can result in esophageal cancer. The treatment is tremendously effective and part of our comprehensive care. It reduces the symptoms and the progression of disease.

It could be all of the above, but GERD has serious implications. It is not just somebody with a stomachache. We know from other populations that acid reflux worsens cough. It worsens asthma. It worsens sinus disease because the vapors come up and continually inflame the upper airway. It can cause chest pain, which some patients misdiagnose and are worried that they are having a heart attack. It can be the beginning of an inflammatory cycle that may lead to esophageal cancer. Barrett's esophagitis can be a problem from GERD: If left untreated, it can result in esophageal cancer. The treatment is tremendously effective and part of our comprehensive care. It reduces the symptoms and the progression of disease.

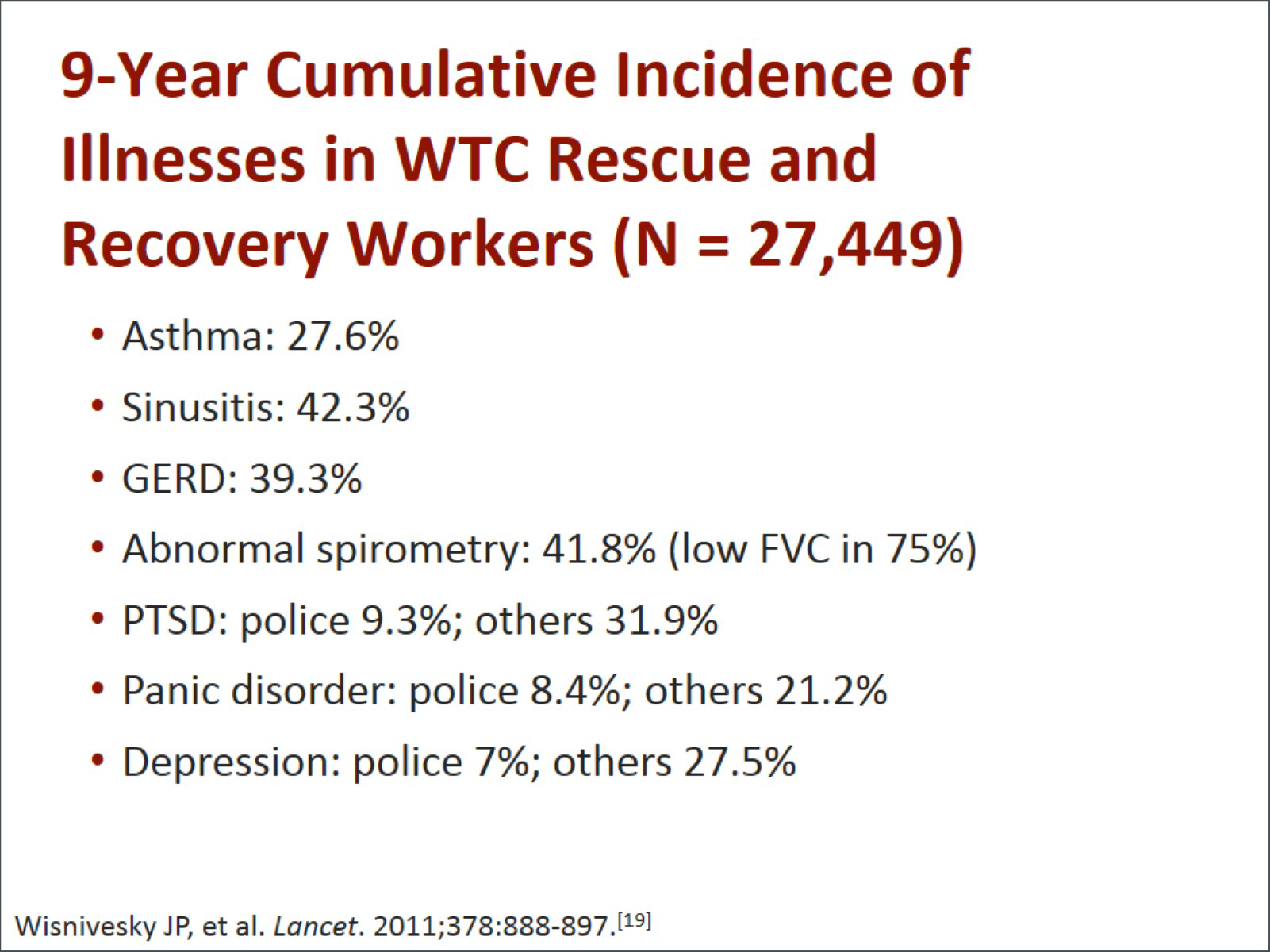

Dr. Crane: These conditions are enormously prevalent in these populations and the responder population. Asthma is now at an incidence of approximately almost 30%. Sinusitis and GERD are seen in around 40% of the population. Abnormal lung function test, which you were discussing, is seen in approximately 40%. Mental health conditions are very, very high. There are some lower end police responders, maybe because of their preparation and training, but other populations exceed 30%. Panic disorder and depression are also extremely prevalent.

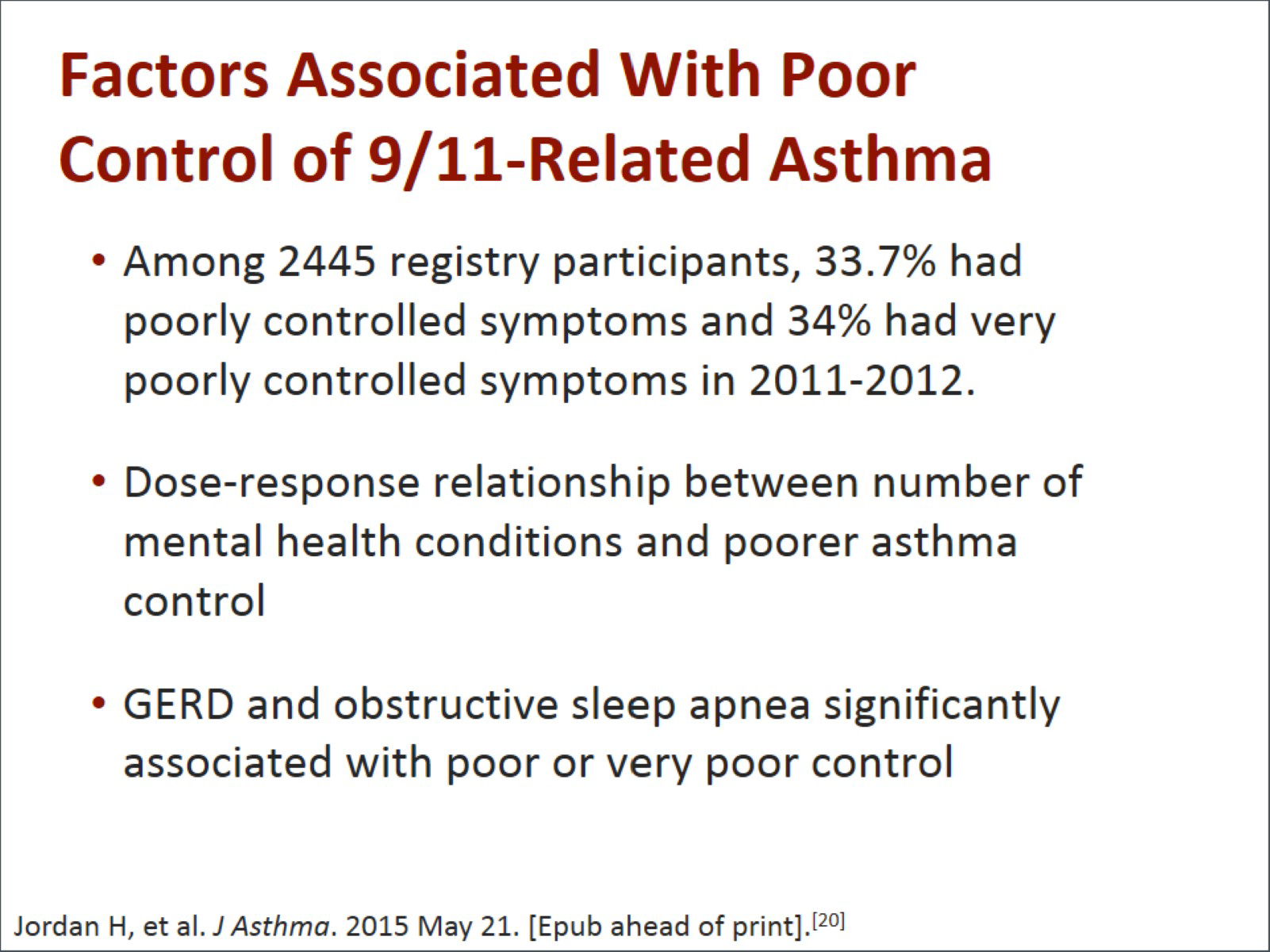

Not only are these things prevalent, but they certainly interact with each other and make the treatment of any one of the conditions a lot more difficult. There is a recent study from the registry that demonstrated that folks suffering from asthma had mostly poorly or very poorly controlled asthma. They were evenly divided: a third controlled, a third poorly controlled, and a third very poorly controlled. There was a dose-responsive relationship between the number of mental health conditions and poor asthma control. The numbers were enormously high, like 11 and 12 times higher. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and obstructive sleep apnea were also significantly associated with poor control. It is not just that they have one of these, they have multiples of these, and this makes it so much harder to treat them. Asthma itself is hard enough to treat, as you pulmonologists know, but this combination is very, very difficult.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: They have many comorbid medical conditions and many comorbid mental health conditions combined.

Dr. Prezant: All interacting.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: I think it is worth adding that the mental health symptoms can play out in many different ways. It can make some people seem more sensitive to some of their medical concerns or some of their medical symptoms, and it can make some people very avoidant, so they end up more symptomatic than they need to be. That is part of why we want to think about this multidisciplinary approach -- so that we can really understand whether someone is being avoidant of medical care. That is why they are more symptomatic than they need to be, or the opposite, that they are really minimizing how serious it is and we need to help them get more involved.

Dr. Crane: It can impact their adherence with medication. What we find, and I am certain you all have found the same thing, is that it is such a barrier for them to even think about the next day that they cannot make appointments. We often have to make appointments for them.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: The medications we use for some of these pulmonary illnesses also have side effects that can seem like mental health side effects. A lot of steroids are used. Asthma pumps can cause some tachycardia afterwards, which can be perceived by some people as a potential onset of a panic. Education is tremendously helpful. If you have clinicians who can foresee this, they also know how to ask their questions. You will not always have a patient tell you that their insomnia temporarily coincides exactly with when they needed the steroids to start. If the steroids are just going to last for 5 days, you can just reassure them that once that is done with, things will be better. That is very different from someone who has been sleeping for years.

Dr. Reibman: What we have been talking about over and over here is that you really need a multidisciplinary approach. We provide that in these Clinical Centers of Excellence. We help pulmonologists; occupational medicine specialists; gastroenterologists; ear, nose, and throat specialists; and oncologists, or we refer to oncologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. You really need all of those people involved, as well as the support staff in terms of nurses, nurse practitioners, administrative staff, and the people who help bring in these difficult-to-reach patients -- the outreach and retention staff.

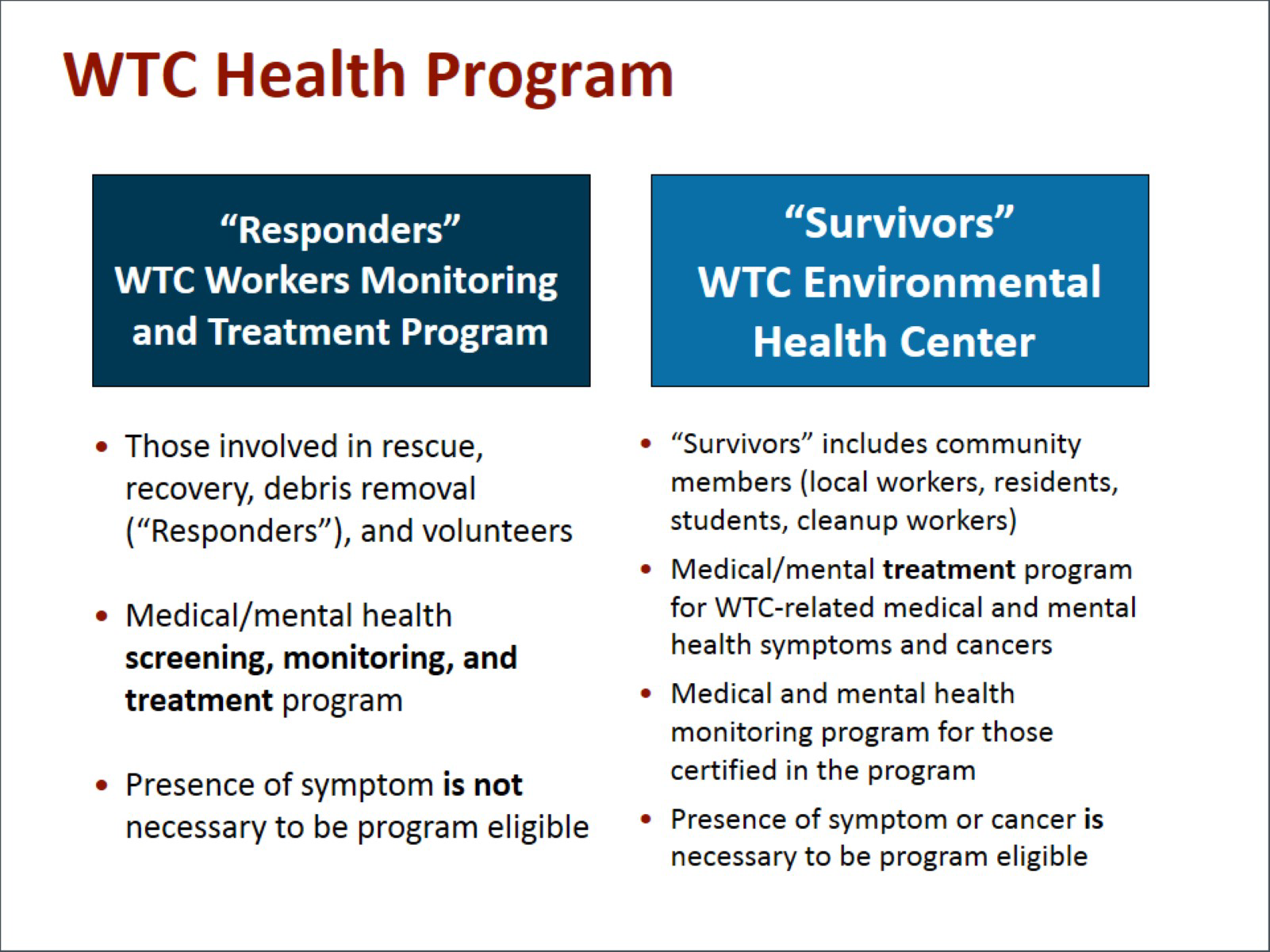

These are provided for in our 3 Centers of Excellence: The Responders, or World Trade Center Workers Monitoring and Treatment Program, the Survivors' World Trade Center Environmental Health Center, and our Nationwide Provider Network. If we were to talk about someone like our first patient who had evacuated a building and is a community member or survivor, she would end up being referred, or hopefully just come, to our survivor program, which is a treatment program for people who have World Trade Center-related illnesses or symptoms.

The other patient that Dr. Prezant talked about would go to the responder program: the FDNY one, or if they were not FDNY, they could go to the responder program in numerous sites around the tristate area. They would both go for treatment but also for routine screening and monitoring. Finally, for people who are not in this local area there is the Nationwide Provider Network, which can provide screening, monitoring, and treatment.

Dr. Levy-Carrick: We have learned a lot over the past 14 years now from our patients and from the research that we have done. To name a few of them, we know about the really high rates of comorbid medical and mental health conditions seen in rescue workers and survivors of the terrorist attack that precipitated an environmental disaster. These lessons learned can be applied in other situations. The comorbid conditions really affect the chronicity of disease, and they affect our treatment planning. Long-term surveillance and treatment of rescue workers and survivors is necessary to better characterize the impact and to inform clinical practice.

Referral to a World Trade Center Health Program for this multidisciplinary approach really recognizes that integration of mental and physical health care can decrease barriers to treatment, stigma, and other barriers to treatment adherence in the wake of it. It sensitizes both medical and mental health teams to screen for these different illnesses, to ask questions that are more specific to them, and to support a patient in navigating the chronic management of his or her diseases.

It really supports a patient's long-term relationship with the clinical center. At the end of the day, we want to meet the patient where they are and to be able to provide as much care as they are able to manage at that time. We want to help them with benefits counseling so they can take in as much as they need. It enhances surveillance. It provides opportunities to support well-being with proactive monitoring, and it improves management of both chronic and the acute on chronic conditions. Some symptoms will wax and wane over the years, and we really want to be able to titrate the intensity of their treatment to that need. Thank you all so much for joining me today in this important discussion.

File Formats Help:

File Formats Help: