We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

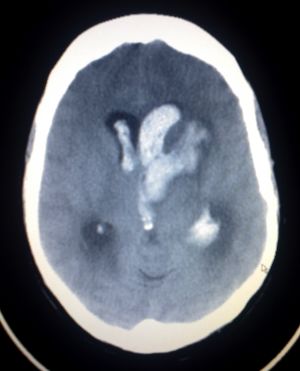

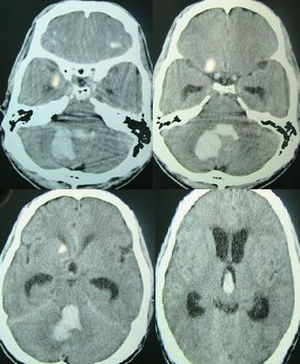

Hemorrhagic stroke

From WikEM

(Redirected from Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH))

Contents

Background

- Also known as "spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage" and sometimes generally as "cerebral hemorrhage"

- ~10% of all acute strokes

- Warfarin use is significant risk factor

- Accounts for 5-15% of all cases

- Risk of ICH doubles for each 0.5 increase in INR above 4.5

Hemorrhagic stroke causes (13% of all strokes)

- Intracerebral

- Hypertension

- Amyloidosis

- Anticoagulation

- Vascular malformations

- Cocaine use

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Berry aneurysm rupture

- Arteriovenous malformation

Clinical Features

- CT required as it is often clinically indistinguishable from SAH, ischemic stroke

- Signs and symptoms suggestive of hemorrhagic stroke

- Vomiting

- SBP >220 mm Hg

- Severe headache

- Coma or decreased LOC

- Symptom progression over minutes or hours all suggest ICH

- HA and nausea and vomiting often precede the neurologic deficit

- Findings dictated by location of bleed (in order of most common)

- Putamen

- Thalamus

- Pons

- Cerebellum

Anterior Circulation

Internal Carotid Artery

- Tonic gaze deviation towards lesion

- Global aphasia, dysgraphia, dyslexia, dyscalculia, disorientation (dominant lesion)

- Spatial or visual neglect (non-dominant lesion)

Anterior Cerebral Artery (ACA)

Signs and Symptoms:

- Contralateral sensory and motor symptoms in the lower extremity (sparing hands/face)

- Urinary incontinence

- Left sided lesion: akinetic mutism, transcortical motor aphasia

- Right sided lesion: Confusion, motor hemineglect

Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA)

Signs and Symptoms:

- Hemiparesis, facial plegia, sensory loss contralateral to affected cortex

- Motor deficits found more commonly in face and upper extremity than lower extremity

- Dominant hemisphere involved: aphasia

- Nondominant hemisphere involved: dysarthria w/o aphasia, inattention and neglect side opposite to infarct

- Contralateral homonymous hemianopsia

- Gaze preference toward side of infarct

Posterior circulation

- Blood supply via the vertebral vertebral artery

- Branches include, AICA, Basilar artery, PCA and PICA

Signs and Symptoms:

- Crossed neuro deficits (i.e., ipsilateral CN deficits w/ contralateral motor weakness)

- Multiple, simultaneous complaints are the rule

- 5 Ds: Dizziness (Vertigo), Dysarthria, Dystaxia, Diplopia, Dysphagia

- Isolated events are not attributable to vertebral occlusive disease (e.g. isolated lightheadedness, vertigo, transient ALOC, drop attacks)

Basilar artery

Signs and Symptoms:

- Quadriplegia, coma, locked-in syndrome

- Sparing of vertical eye movements (CN III exits brainstem just above lesion)

- Thus, may also have miosis b/l

- One and a half syndrome (seen in a variety of brainstem infarctions)

- "Half" - INO (internuclear opthalmoplegia) in one direction

- "One" - inability for conjugate gaze in other direction

- Convergence and vertical EOM intact

- Medial inferior pontine syndrome (paramedian basilar artery branch)

- Ipsilateral conjugate gaze towards lesion (PPRF), nystagmus (CN VIII), ataxia, diplopia on lateral gaze (CN VI)

- Contralateral face/arm/leg paralysis and decreased proprioception

- Medial midpontine syndrome (paramedian midbasilar artery branch)

- Ipsilateral ataxia

- Contralateral face/arm/leg paralysis and decreased proprioception

- Medial superior pontine syndrome (paramedian upper basilar artery branches)

- Ipsilateral ataxia, INO, myoclonus of pharynx/vocal cords/face

- Contralateral face/arm/leg paralysis and decreased proprioception

Superior Cerebellar Artery (SCA)

- ~2% of all cerebral infarctions[1]

- May present with nonspecific symptoms - N/V, dizziness, ataxia, nystagmus (more commonly horizontal)[2]

- Lateral superior pontine syndrome

- Ipsilateral ataxia, n/v, nystagmus, Horner's syndrome, conjugate gaze paresis

- Contralateral loss of pain/temperature in face/extremities/trunk, and loss of proprioception/vibration in LE > UE

Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA)

Signs and Symptoms:

- Common after CPR, as occiptal cortex is a watershed area

- Unilateral headache (most common presenting complaint)

- Visual field defects (contralateral homonymous hemianopsia, unilateral blindness)

- Visual agnosia - can't recognize objects

- Possible macular sparing if MCA unaffected

- Motor function is typically minimally affected

- Lateral midbrain syndrome (penetrating arteries from PCA)

- Ipsilateral CN III - eye down and out, pupil dilated

- Contralateral hemiataxia, tremor, hyperkinesis (red nucleus)

- Medial midbrain syndrome (upper basilar and proximal PCA)

- Ipsilateral CN III - eye down and out, pupil dilated

- Contralateral paralysis of face, arm, leg (corticospinal)

Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery (AICA)

- Lateral inferior pontine syndrome

- Ipsilateral facial paralysis, loss of corneal reflex (CN VII)

- Ipsilateral loss of pain/temp (CN V)

- Nystagmus, N/V, vertigo, ipsilateral hearing loss (CN VIII)

- Ipsilateral limb and gait ataxia

- Ipsilateral Horner syndrome

- Contralateral loss of pain/temp in trunk and extremities (lateral spinothalamic)

Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery (PICA)

Signs and Symptoms:

- Lateral medullary/Wallenberg syndrome

- Ipsilateral cerebellar signs, ipsilateral loss of pain/temp of face, ipsilateral Horner's syndrome, ipsilateral dysphagia and hoarseness, dysarthria, vertigo/nystagmus

- Contralateral loss of pain/temp over body

- Also caused by vertebral artery occlusion (most cases)

Internal Capsule and Lacunar Infarcts

- May present with either lacunar c/l pure motor or c/l pure sensory (of face and body)[3]

- Pure c/l motor - posterior limb of internal capsule infarct

- Pure c/l sensory - thalamic infarct (Dejerine and Roussy syndrome)

- C/l motor plus sensory if large enough

- Clinically to cortical large ACA + MCA stroke - the following signs suggest cortical rather than internal capsule[4]:

- Gaze preference

- Visual field defects

- Aphasia (dominant lesion, MCA)

- Spatial neglect (non-dominant lesion)

- Others

- I/l ataxic hemiparesis, with legs worse than arms - posterior limb of internal capsule infarct

Anterior Spinal Artery (ASA)

Superior ASA

- Medial medullary syndrome - displays alternating pattern of sidedness of symptoms below

- Contralateral arm/leg weakness and proprioception/vibration

- Tongue deviation towards lesion

Inferior ASA

- ASA syndrome

- Watershed area of hypoperfusion in T4-T8

- B/l pain/temp loss in trunk and extremities (spinothalamic)

- B/l weakness in trunk and extremities (corticospinal)

- Preservation of dorsal columns

Differential Diagnosis

Intracranial Hemorrhage

- Intra-axial

- Hemorrhagic stroke (Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage)

- Traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage

- Extra-axial

- Epidural hemorrhage

- Subdural hemorrhage

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (aneurysmal intracranial hemorrhage)

Evaluation

Stroke Work-Up

- Labs

- POC glucose

- CBC

- Chemistry

- Coags

- Troponin

- T&S

- ECG

- In large ICH or stroke, may see deep TWI and prolong QT, occ ST changes

- Head CT (non-contrast)

- Also consider:

- CTA brain and neck (to check for large vessel occlusion for potential thrombectomy)

- Pregnancy test

- CXR (if infection suspected)

- UA (if infection suspected)

- Utox (if ingestion suspected)

MR Imaging (for Rule-Out CVA or TIA)

- MRI Brain with DWI (without contrast) AND

- Cervical vascular imaging (ACEP Level B in patients with high short-term risk for stroke):[8]

- MRA brain (without contrast) AND

- MRA neck (without contrast)

- May instead use Carotid CTA or US (Carotid US slightly less sensitive than MRA)[9] (ACEP Level C)

Management

Elevating head of bed

- 30 degree elevation will help decrease ICP[10]

Blood Pressure

- Few studies on optimal management however many guidelines recommending moderate reduction, often a goal systolic of 140-160's

- Rapid SBP lowering <140 has been advocated with early research showing improved functional outcome[11], but more recent work has found no difference between SBP <140 and <180[12]

- SBP >200 or MAP >150

- Consider aggressive reduction w/ continuous IV infusion

- SBP >180 or MAP >130 and evidence or suspicion of elevated ICP

- Consider reducing BP using intermittent or continuous IV meds to keep CPP >60-80

- SBP >180 or MAP >130 and NO evidence or suspicion of elevated ICP

- Consider modest reduction of BP (e.g. MAP of 110 or target BP of 160/90)

Reverse coagulopathy

Heparin

- Give protamine 1mg/100units of heparin based on time since last dose

Warfarin

- Stop warfarin

- Give Vitamin K 5-10mg IV INR will decrease over 24-48 hours (small risk of anaphylaxis with IV Vitamin K)

- Give 4 Factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC)

- If no PCC, then give 15 ml/kg fresh frozen plasma (no benefit to combining PCC and FFP)

Antiplatelet

- Includes aspirin, prasagril, clopidogrel

- Consider Desmopressin (0.3mcg/kg)

- Transfusion of platelets has been shown to increase mortality[13]

Fondaparinux or Rivaroxaban

- rFVIIa 2mg (40 mcg/kg)

- Or PCC 25-50 U/kg

- Don't give both 2/2 to prothrombotic effects

Dabigatran

- Idarucizumab (Praxbind): 5 grams IV (approved as of October 2015)

- rFVIIa 100 mcg/kg

- Or PCC 25-50 U/kg

- Consider DDAVP 0.3 mcg/kg

- Hemodialysis, if feasible

Intubation

- Consider neuroprotective intubation

- Ensure patient is pain-free for post-intubation sedation

- Propofol with fentanyl

- Try to prioritize pain control with fentanyl

AHA Spontaneous ICH BP Guidelines 2015[15]

- If SBP is 150-220mmHg without contraindication to BP lowering, it is safe to acutely lower BP to 140mmHg and can be effective for improving functional outcome. (Class I Level A)

- For ICH patients presenting with SBP >220 mm Hg, it may be reasonable to consider aggressive reduction of BP with a continuous intravenous infusion and frequent BP monitoring (Class IIb; Level of Evidence C)

AHA ICH Coagulopathy Guidelines 2015[16]

- Patients with a severe coagulation factor deficiency or severe thrombocytopenia should receive appropriate factor replacement therapy or platelets, respectively (Class I; Level of Evidence C). (Unchanged from the previous guideline)

- Patients with ICH whose INR is elevated because of VKA should have their VKA withheld, receive therapy to replace vitamin K–dependent factors and correct the INR, and receive intravenous vitamin K (Class I; Level of Evidence C). PCCs may have fewer complications and correct the INR more rapidly than FFP and might be considered over FFP (Class IIb; Level of Evidence B). rFVIIa does not replace all clotting factors, and although the INR may be lowered, clotting may not be restored in vivo; therefore, rFVIIa is not recommended for VKA reversal in ICH (Class III; Level of Evidence C). (Revised from the previous guideline)

- For patients with ICH who are taking dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban, treatment with FEIBA, other PCCs, or rFVIIa might be considered on an individual basis. Activated charcoal might be used if the most recent dose of dabigatran, apixaban, or riva- roxaban was taken <2 hours earlier. Hemodialysis might be considered for dabigatran (Class IIb; Level of Evidence C). (New recommendation)

- Protamine sulfate may be considered to reverse hep- arin in patients with acute ICH (Class IIb; Level of Evidence C). (New recommendation)

- The usefulness of platelet transfusions in ICH patients with a history of antiplatelet use is uncer- tain (Class IIb; Level of Evidence C). (Revised from the previous guideline)

- Although rFVIIa can limit the extent of hematoma expansion in noncoagulopathic ICH patients, there is an increase in thromboembolic risk with rFVIIa and no clear clinical benefit in unselected patients. Thus, rFVIIa is not recommended (Class III; Level of Evidence A). (Unchanged from the previous guideline)

Disposition

- Admission for acute or subacute

See Also

External Links

References

- ↑ Macdonell RA, Kalnins RM, Donnan GA. Cerebellar infarction: natural history, prognosis, and pathology. Stroke. 18 (5): 849-55.

- ↑ Lee H, Kim HA. Nystagmus in SCA territory cerebellar infarction: pattern and a possible mechanism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013 Apr;84(4):446-51.

- ↑ Rezaee A and Jones J et al. Lacunar stroke syndrome. Radiopaedia. http://radiopaedia.org/articles/lacunar-stroke-syndrome.

- ↑ Internal Capsule Stroke. Stanford Medicine Guide. http://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/the25/ics.html

- ↑ Mullins ME, Schaefer PW, Sorensen AG, Halpern EF, Ay H, He J, Koroshetz WJ, Gonzalez RG. CT and conventional and diffusion-weighted MR imaging in acute stroke: study in 691 patients at presentation to the emergency department. Radiology. 2002 Aug;224(2):353-60.

- ↑ Suarez JI, Tarr RW, Selman WR. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(4):387–396.

- ↑ Douglas VC, Johnston CM, Elkins J, et al. Head computed tomography findings predict short-term stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2003;34:2894-2899.

- ↑ ACEP Clinical Policy: Suspected Transient Ischemic Attackfull text

- ↑ Nederkoorn PJ, Mali WP, Eikelboom BC, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of carotid artery stenosis. Accuracy of noninvasive testing. Stroke. 2002;33:2003-2008.

- ↑ http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/38/6/2001.full

- ↑ Anderson CS, Heeley E, Huang Y, et al. Rapid blood-pressure lowering in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:2355-2365.

- ↑ Qureshi AI, Palesch YY, Barsan WG, et al. Intensive Blood-Pressure Lowering in Patients with Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2016; 1-11. [Epub ahead of print].

- ↑ Baharoglu MI, Cordonnier C, Salman RA, et al. Platelet Transfusion Versus Standard Care After Acute Stroke due to Spontaneous Cerebral Haemorrhage Associated with Antiplatelt Therapy (PATCH): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet. 2016; 1 – 9. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ Bucher J and Koyfman A. Intubation of the neurologically injured patient. J Emerg Med. 2016; 49:920-927.

- ↑ Hemphill JC, et al. AHA/ASA Guideline: Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015.

- ↑ Hemphill JC, et al. AHA/ASA Guideline: Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015.