Malaria Visits a Child in Africa

The child in this story (Courtesy: The Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre and the Rufiji District Council Health Management Team, Tanzania)

Ramadhani Shida Mashaka* was only 8 months old when he got seriously ill, but it did not seem to be very bad at first. His young mother, Zainabu, noticed he had a fever one afternoon, but the child was still able to eat and play and did not seem to be bothered. "Sometimes these simple fevers can go as quickly as they come", she thought. The fever continued throughout the night and the next morning the child seemed very sleepy and his body felt very hot.

Zainabu wasn't sure what to do. She was new to the village of Njopeka in coastal Tanzania, having just moved there after her marriage last year. She had attended the antenatal clinic and taken Ramadhani for his baby shots at the free health clinic in their village. However, the clinic almost always ran out of medicines in the latter part of the month and she had very little money to go elsewhere.

What's more, Zainabu had to decide on her own what to do for the child. The boy's father, Shida, had left home about 2 months ago. He had been hired to cut logs in the forest, 90 kilometers (56 miles) to the south. Shortly after leaving home, Shida sent money back to his family but he had been unable to do so again.

Malaria is a frequent but unwelcome visitor to the children of Africa. (Courtesy: National Malaria Control Program, Democratic Republic of Congo)

Home treatment

The following day, after another night during which Ramadhani remained restless and feverish, Zainabu decided to ask a neighbor for help. Fortunately, Mama Tatu lived nearby. When Mama Tatu was a young woman she began training as a nurse, but she left the college when she got married and had children. People in the village often sought her advice when someone was ill. She didn't demand any payment but frequently her neighbors would offer whatever they could.

Zainabu was relieved when Mama Tatu told her that the boy probably just had a simple bout of malaria. Mama Tatu gave her some chloroquine tablets that she'd kept in her home. Chloroquine used to be the pill of choice for malaria, but nurses and doctors in the area said it no longer was able to cure the type of malaria found there. Thus, chloroquine was no longer available in health centers or at drug shops. (Editorial comment: Because of the widespread emergence of malaria parasites resistant to chloroquine in Africa, ministries of health in most African countries have decided not to use that drug to treat malaria anymore. They have replaced it with other, more effective antimalarial drugs; in Tanzania, this change in drug use policy occurred in 2001.) Nonetheless many of the local people still preferred chloroquine and had come to rely on Mama Tatu's supply. After giving the tablets to Ramadhani, Zainabu noticed that he seemed to improve. His body no longer felt hot and he began to play and eat as usual. For a while, it looked like the illness had passed.

Ramadhani seemed well for 4 or 5 days, but then the fever returned. It wasn't very bad when Zainabu first noticed it in the early morning, but she did not want to wait for it to worsen. Her father-in-law, Mashaka, was preparing to carry a load of cassava root on his bicycle, hoping to sell it in the shifting market at Mkiu, 12 km (8 miles) north near the end of the paved road from Dar-es-Salaam. Zainabu asked her father-in-law to help her by buying some fever medicine for Ramadhani at one of the drug shops in Mkiu. When he returned home that evening, he brought some Panadol tablets to Zainabu. (Editorial comment: Panadol is a brand name for paracetamol, a drug that alleviates fever and pain, two symptoms associated with malaria; however paracetamol has no effect on the malaria parasites themselves.) These she crushed in water and tried to get the child to swallow. By this time, however, Ramadhani was very weak and began refusing to eat or drink. Zainabu kept trying to get the child to take the medicines throughout the night. By morning the child was still refusing to eat or drink. His breathing had become very fast.

A shifting market in Tanzania (Courtesy: The Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre and the Rufiji District Council Health Management Team, Tanzania)

Seeking treatment outside the home

Zainabu knew the child was very seriously ill and needed to get to a health facility right away. But the clinic in the village would have no medicines by now, near the end of the month; and the doctors would only recommend that she buy medicines from the shop or take the child to an expensive mission hospital. Again, she asked her father-in-law, and he suggested taking the boy to a larger government clinic where services would be free. One had recently begun operating 6 km (4 miles) away, just over the border in the next district in the village of Jaribu-Mpakani. In fact, the shifting market would be held there that very day.

Mashaka agreed to take mother and child to the clinic there and he would take advantage of another opportunity to sell his cassava. Zainabu bathed herself and the baby and selected their best clothing. Then she quickly slipped onto the back of Mashaka's bicycle, with Ramadhani on her back, and gripping the cassava bundle with one hand.

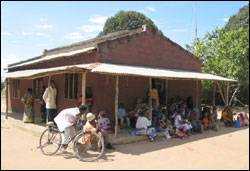

The dispensary

When they arrived at the Jaribu-Mpakani Dispensary there were already dozens of patients surrounding it, waiting to see the health workers. Zainabu took her place in the queue. Not long before, there had been no government health facility in any of the nearby villages. Locally elected leaders in Jaribu-Mpakani had organized their neighbors to build a small dispensary and eventually succeeded in persuading the district health officials to staff and supply it. A young clinical officer, Imani Kadula, was assigned to the post fresh out of his training college.

When it was Zainabu and Ramadhani's turn to enter the consultation room, Imani asked Zainabu about the boy's condition and what treatments they had already tried. He felt the child, looked at his hands, and counted his breathing. Imani told Zainabu that the child had a severe illness: most probably caused by malaria or pneumonia or both. Without a laboratory or x-ray, which the dispensary did not have, it was impossible to tell which. In this situation, he advised that the child should be treated for both, as well as for anemia, which had made the child pale and contributed to his poor condition. When children get malaria infection, he explained, some medicines can reduce the fever but don't affect the germs that cause the disease. While the patient might appear to get some relief from the symptoms, malaria germs continue to destroy the patient's blood cells, causing anemia and making the child very vulnerable to even minor infections. Sometimes the malaria-induced anemia can be so severe that children require a blood transfusion. (Editorial comment: Malarial anemia is a leading cause for blood transfusions in African children. Transfusions, if not well screened, carry risks for transmission of infectious agents such as HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.)

The Jaribu-Mpakani dispensary (Courtesy: The Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre and the Rufiji District Council Health Management Team, Tanzania)

Because the boy was too ill to swallow medicines, Imani's training had taught him to give an injection to start the treatment and to recommend that the family take the boy to a hospital at once. Zainabu explained that she had no money for transport or to pay the fees that would be necessary to get treatment at the nearest hospital — one operated by a Christian mission another 50 km (31 miles) away.

Imani understood her predicament; it's one faced by many of his patients. His training had also included provisions for what to do in situations where referral was not possible.

He proposed that they give the first doses of malaria medicine and antibiotics for pneumonia by injection immediately. Then they would watch and see if the boy improved before the late afternoon. After that Imani continued to evaluate and treat the other patients.

By late afternoon the child was improving and appeared well enough to swallow medicines. One of the nursing assistants, Bibi Kuruthumu, had worked at the district hospital for almost 20 years before being assigned to the dispensary at Jaribu-Mpakani. She was very experienced at helping mothers get their children to swallow medicines. She prepared a dose of a new combination treatment for malaria: one that included tablets of an artemisinin containing combination therapy. (Editorial comment: while the injection of quinine can act rapidly to save the life of a patient who cannot take drugs by mouth, other drugs must be added later to ensure that all the malaria germs are completely cleared from the patient's body.) She crushed the tablets and mixed them with a spoonful of water, then carefully coaxed the boy to swallow the mixture down.

Zainabu, to her relief, watched as the child swallowed the medicine without difficulty. Because it was late and Imani was still concerned about the child, he convinced Zainabu and Mashaka not to return home until morning. The small dispensary had no ward for admitting patients, but there was a cot and a bed in the labor room which was not in use. Bibi Kuruthumu encouraged Zainabu to spend the night there and loaned her some bedding materials. Zainabu's father-in-law had managed to sell his cassava and purchased some food for them both.

A happy ending (for now)

Zainabu woke the next morning and was greatly relieved. Ramadhani had slept through the night; his breathing calmed and his body was no longer hot to the touch. When he awoke, he was alert and showed a good appetite for the first time in days. Bibi Kuruthumu, Imani and the rest of the clinic workers were delighted at the child's improvement and counseled Zainabu to continue giving the rest of the medicines until they were completely finished. Even though the child had improved, the malaria could bounce back if the whole treatment wasn't completed. More importantly, the whole 3-day course of treatment was necessary to give the child's body a chance to recover completely from the anemia. Bibi Kuruthumu showed Zainabu how to crush the tablets and patiently get the child to swallow them. She also suggested that the next time her husband sent money home, Zainabu should consider getting an insecticide-treated mosquito net. (Editorial comment: Insecticide-treated bednets have now been adopted by most African countries as an important tool for preventing malaria.) Later that morning Mashaka, Zainabu and Ramadhani thanked the clinic workers and returned home to Njopeka.

* Names of the patient, family members and neighbors have been changed. Other details are authentic and used with permission. This scenario is a very common occurrence in sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria is a leading cause of death and disease in young children.

(Contributed by the Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre and the Rufiji District Council Health Management Team, Tanzania.)

- Page last reviewed: February 8, 2010

- Page last updated: February 8, 2010

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir