Living with a Congenital Heart Defect

Many adults with some types of CHDs need to be cared for by physicians with additional training in caring for adults with CHDs. To help find a provider with this expertise, visit the Adult Congenital Heart Association’s Clinic Directory.

As medical care and treatment have improved, babies and children with CHDs are living longer and healthier lives. Most are now living into adulthood. Ongoing, appropriate medical care can help children and adults with a CHD live as healthy as possible.

Health Care

It is important for parents of children with a heart defect and adults living with a heart defect to talk with a heart doctor (cardiologist) regularly. Regular visits with a cardiologist are important, because they allow the parents of children with heart defects to make the best possible choices for the health of their child. These visits also allow adults living with a heart defect to make the best possible choices for their own health.

Children and adults with CHDs can help with their health care by knowing their medical history, including the:

- Type(s) of heart defect(s) they have.

- Procedures or surgeries they have had performed.

- Medicines and doses of these medicines that they are prescribed currently and were prescribed in the past.

- Type(s) of medical care they are receiving now.

As children transition to adult health care, it is important to notify any new healthcare provider(s) about the child’s CHD. Ongoing appropriate medical care for their specific heart defect will help children and adults with a CHD to live as healthy a life as possible.

Stories: Living with a Congenital Heart Defect

William’s Story

I was born with a heart defect, tetralogy of Fallot, in 1954. My parents were told that I would not survive even a year. At that time, the option of surgery was new and very few doctors were skilled in this type of procedure. In 1966, at the age of eleven, I had corrective surgery. The medical care had advanced and I was very lucky. I was doing well until May of 1969, when we discovered that my heart rate was dangerously low: less than 30 beats per minute. So, on May 21, 1969, I got my first pacemaker. Again, because of new developments in medical care, I was lucky. Advances in pacemaker technology have continually improved my quality of life. Today, I am 58 years old and have an implanted cardiac defibrillator.

Due to the advances in medical care, today, children can get the care they need within the first few weeks of life. If I was born today with the same heart defect, the surgery would be done at 4-8 weeks of age. As the medical community learns and moves forward, people with heart defects have and will benefit as a result. Now, we live longer, healthier lives. However, our surgery is not a total cure, and, as we age, we still suffer effects of these conditions. Continued medical care and ongoing research is vitally important to each of our lives.

Nick’s Story

As Susan welcomed the birth of her son Nick, she thought everything seemed normal. However, as she asked, “Is my baby fine?” the initial smiles surrounding her quickly changed to whispers and concerned looks. Soon, Nick was whisked away to specialists in a large children’s hospital while Susan was left behind. Shortly afterward, she was released, leaving with a balloon that read “It’s a boy!” but she held no baby boy in her arms. Susan did not realize then that the adventure had only begun as tests soon revealed that her baby had a congenital heart defect.

After Nick had three difficult open heart surgeries, his doctors decided that he could survive only with a heart transplant. Just before his second birthday, Nick received his new heart. Although Nick is 23 years old now and doing well, he and his parents still worry about transplant rejection and the future. “I think about the pain and frustration we have been through, and my hope for other families is that we can find out what causes congenital heart defects so that we can prevent them,” added Susan.

Asha's Story

Here is my incredible journey as a congenital heart patient. I was born with four defects in the heart called tetralogy of Fallot, commonly known as “blue baby”. In the 1960s in India, open heart surgeries were unheard of. Uncorrected, this condition rarely survives into adulthood. At age 4, I had a procedure to help my blood bypass the problems in my heart, which helped me attend school. Trying my best to be “normal” despite a long “do-not-do” list, I completed high school. I had a growth spurt at age 15, and my student life came crashing down, as daily school attendance became a challenge. In 1976, I was given a 5% chance of survival for an open-heart surgery. The decision was momentous both to me and my family. The 8-hour surgery involved not only correcting the defects, but also fixing what had been done in my previous procedure. The result of the surgery was unknown for about 72 hours, but I pulled through with only a scar infection as a complication. A three month stay in the hospital was followed by a year of a salt-free diet and no school.

Having survived the open-heart surgery (called total correction), I became a medical example. My spirit demanded an unusual education. With the doctor’s permission, I opted to become a software engineer, and took up a career in information technology. I met a man who was brave enough to take me on for a spouse, and we moved to Scotland where I began a Master’s program. Thirteen years after the open-heart surgery, a new murmur led to the discovery of the results of the initial procedure coming undone. I was shuttled to Glasgow to a pediatric surgical center to fix it.

In 1992, we moved to the US and in 1997, I had a daughter – a 32 week preemie. Motherhood and pregnancy took a toll and by 2002, I began to feel breathless and exhausted. My pulmonary valve needed to be replaced. Again, it was yet another pediatric hospital and pediatric heart surgeon who fixed me. This time the survival rate given was 99% and only a week’s hospital stay!

I am one of the first groups of adults alive with this congenital heart defect. We form a new population whose healthcare needs have not yet been studied and whose prognosis and life-expectancy are still unknown. Recently, I experienced heart palpitations requiring medication to slow my heart. A new unexpected defect in the left side of the heart has also come to light, making me a “rare” case. Patients living into adulthood and their doctors now face the unknown. Stepping into the sixth decade of life, I realized that my heart will never be totally corrected. Hence, I will need life-long monitoring at a specialized health clinic. My advice to others like me is to contact specialized clinics and face the unknown together with the doctors. Public health has a very important role in helping such patients with much needed research.

Shandler's Story

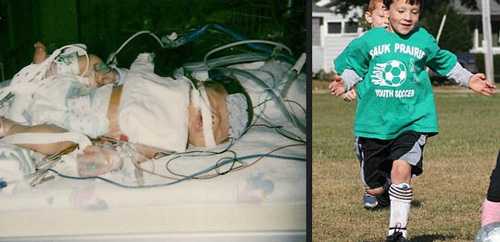

Our twins, a boy and girl, were born 6 weeks premature in 2002. Our son, Shandler, was born with two congenital heart defects: coarctation of the aorta and bicuspid aortic valve. Coarctation of the aorta is a narrowing of part of the aorta (the major artery that supplies oxygenated blood to the entire body). Bicuspid aortic valve is an aortic valve that has two leaflets, instead of three. Shandler was fairly small, weighing only 4 pounds. At four days old, he began to have difficulty breathing. The doctors detected a heart murmur, and diminished pulses in his legs and feet. Through echocardiography (ultrasound of the heart), the congenital heart defects were found. Three days later, the heart surgeon repaired the coarctation. There is no intervention for his bicuspid aortic valve.

Our family was absolutely terrified that he wouldn’t survive major heart surgery because of how tiny he was. He did well for about two weeks after surgery, and then he developed complications (a risk with any surgical procedure). Fluid collected around his lungs, making it difficult for him to breathe. He required a ventilator to assist with breathing and chest tubes placed to drain the fluid. After six weeks of no improvement in his condition, as well as developing bacterial meningitis (which almost took his life), he was taken back into surgery. Within 24 hours, he was able to breathe on his own again. After 11 weeks in the newborn intensive care unit, Shandler was finally able to come home, to be reunited with his twin sister and live with our family. However, he was discharged with a feeding tube. This was necessary because his heart condition caused fatigue during feedings, and he was not able to take the full amount necessary by mouth.

The past 10 years have had their ups and downs for our family. Shortly after coming home, Shandler developed a condition called dysphagia, due to severe acid reflux. Dysphagia is a problem with swallowing. Shandler started refusing to eat. He later had a feeding tube surgically placed, which was how he received his nutrition for several years. Just before turning 4, he was finally eating and drinking enough to have the tube removed.

His heart condition made him extremely fragile the first few years of life. As an infant, he was hospitalized for several weeks (in critical condition) in the pediatric intensive care unit, with complications from flu. At age 2, he contracted respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and was hospitalized for 1 week due to breathing difficulty.

Seeing Shandler today, you wouldn’t know he had such a rough start in life. Although he is small for his age, he is able to run and play with his peers, and eats everything in sight!! However, he does require yearly follow-up by a cardiologist. Through echocardiography, they look for any signs of aortic narrowing again, as well as checking the function of his bicuspid aortic valve. Complications of bicuspid aortic valve include: congestive heart failure, leakage of blood through the valve back into the heart, and narrowing of the valve’s opening. The valve will require repair or replacement if this occurs. Shandler is never allowed to participate in contact sports (football, hockey and wrestling). Despite this restriction, he is a bright, happy 5th grader, who loves to play jokes on others (especially his sisters). He enjoys building things, reading Harry Potter books, and is a whiz in math and other school subjects. He will always have his “battle scar”, although he jokes that it “makes him look tough”!! We have been truly blessed to have Shandler in our family.

Nicholas's Story

"Are you sitting down? Your baby has a serious heart defect." This phone call was supposed to be my mother, congratulating us as we brought our baby home for the first time. Instead, it marked the beginning of a whirlwind, which resulted in three hospitals, a helicopter ride and heart surgery, all in the first four days of Nicholas' life. Nicholas was born with a serious heart defect called critical coarctation of the aorta, a severe narrowing in his aorta cutting off blood flow to the lower half of his body.

The first couple of years of Nick's life were filled with caution, fear and anxiety, and they were consumed by doctors’ visits. This was compounded by the fact that there were always two other siblings in tow. The inside of my minivan was decorated with the hundreds of "good patient" stickers the three of them had collected. These stickers meant Nicholas had made it another day.

Truthfully, Nicholas is a poster child for successful surgery. He has done so well that the doctors’ visits have tapered off to a bi-annual cardiology visit. He is able to participate in sports with soccer and swimming topping his list, although hip-hop dancing is his favorite. Most days, it's easy to forget that he has a serious defect. Yet, occasionally, I catch myself wondering what his future holds. Until recently, children with severe heart defects didn't survive and there is a huge gap of information about adults with heart defects.

There are still questions: How? Why? What's next? No one really knows. I do know, that I will do everything I can to make sure he lives a long and healthy life.

Ken'sStory

My name is Ken, and I was born in 1981 with congenital heart disease (CHD). I had my first (and, so far, only) open heart surgery at the age of eight months to correct a defect known as tetralogy of Fallot. Like many people with CHD, I thought that the surgery had fixed me, and I was lost to cardiology care as an adolescent. I am incredibly fortunate in that I have enjoyed a healthy and active life that is somewhat unusual for people with CHD. I have always loved cycling; and in 2005, I completed my first endurance ride: 2 days and 180 miles between Illinois and Wisconsin. Since then, I have continued to pursue this passion by participating in multiple endurance rides across the country, including the 7-day, 560-mile AIDS/LifeCycle ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles in 2010.

The journey continues, and I am looking forward to the ride!

Care Across the Lifespan

Affordable Care Act

Affordable Care Act: Improving the Lives of People with Congenital Heart Defects

People with congenital heart defects can require a great deal of care, in many cases lifelong. The American Heart Association recently published a new fact sheet that describes how the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is already benefiting persons and families affected by congenital heart defects. Click here to learn more from the American Heart Association or visit www.healthcare.gov.

At this time, even with improved treatments, many people with a CHD are not cured, even if their heart defect has been repaired. As a person with a heart defect grows and gets older, further heart problems may occur. Additional medications, surgeries, or other procedures may be needed after the initial childhood surgeries. Some people with heart defects need lifelong care to stay as healthy as possible and address certain health issues:

Nutrition

Some babies with a CHD can become tired while feeding and might not eat enough to gain weight. Furthermore, because of the extra work that their heart may have to do to compensate for having a defect, some children with CHDs burn more calories. As they grow up, these children might be smaller and thinner than other children. After treatment for their heart defect, growth and weight gain often improve. It is important to talk with a healthcare provider about diet and nutrition.

Medications

Some children and adults with a CHD will need medicine to help with problems associated with their heart defect. For example, some medicines help make the heart stronger, and others help lower blood pressure. It is important for children and adults with a CHD to take medications as prescribed.

Physical activity

Physical activity is an important part of staying healthy, and it can help the heart become strong. Adults and parents of children with a CHD should discuss with their healthcare providers which physical activities are safe for them or their children, respectively, and if there are any physical activities that should be avoided.

Pregnancy

Women with CHDs who are considering having a baby should talk with a healthcare provider before becoming pregnant to discuss how the pregnancy might affect them or their baby, or both. Many women with a heart defect have healthy, uneventful pregnancies. However, having a CHD is the most common heart problem for pregnant women. Pregnancy can put stress on the heart of women with some types of heart defects. The woman might need to have procedures done related to her heart condition before becoming pregnant or take certain medications to help her heart during pregnancy. Her baby also might be at risk for having a heart defect, so talking with a genetic counselor could be helpful.

Other Potential Health Problems

Many people with a CHD live independent lives. Some people with a heart defect have little or no disability. For others, disability might increase or develop over time. People with a heart defect might also have genetic problems or other health conditions that increase the risk for disability. People with a CHD can develop other health problems related to their heart defect over time. These problems may depend on their specific heart defect, the number of heart defects they have, and the severity of their heart defect.

Some health problems that might need treatment include:

Infective Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis is an infection in the layers of the heart. If left untreated, it can lead to other problems, such as a blood clot, heart valve damage, or heart failure. Guidelines recommend that individuals with certain heart defects take oral antibiotics before having certain procedures, such as dental or surgical procedures. However, these guidelines have been updated, and many people with a CHD, such as those with valve stenosis or an unrepaired ventricular septal defect, no longer need to take antibiotics before procedures. Each person should discuss his or her condition with the doctor to find out if antibiotics are recommended for him or her.

Arrhythmia

Arrhythmia is a problem with how the heart beats. The heart can beat too fast, too slow, or irregularly. This can lead to a problem with the heart not pumping enough blood out to the body and can increase the risk for blood clots. Some people with a heart defect can have an arrhythmia associated with their heart defect or as a result of past treatments or procedures for their heart defect. Some people can have an arrhythmia even in the absence of any heart defects.

Pulmonary Hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension is high blood pressure in the arteries (blood vessels) that lead from the heart to the lungs. Certain heart defects can cause pulmonary hypertension, which forces the heart and lungs to work harder. If the pulmonary hypertension is not treated, over time the right side of the heart can become enlarged, and heart failure can occur.

Liver Disease

People with single ventricle heart defects can develop liver disease associated with their heart defect or as a result of past treatments or procedures for their heart defect. It is important for people with this type of heart defect to see a healthcare provider regularly to stay as healthy as possible.

Other Conditions

As adults with CHDs age, they can get other diseases of adulthood, such as diabetes, obesity, or atherosclerosis (buildup of cholesterol in the arteries). However, because of the problems associated with a CHD, these diseases might affect adults with a CHD differently from adults without a CHD. Therefore, they must have annual follow-up visits with cardiologists who are trained to care for adult patients with a CHD.

- Page last reviewed: May 18, 2016

- Page last updated: May 18, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir