Career Probationary Fire Fighter and Captain Die as a Result of Rapid Fire Progression in a Wind-Driven Residential Structure Fire Texas

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2009-11 Date Released: April 8, 2010

Revised on January 4, 2011 to add NPPTL SCBA Evaluation report.

Revised on December 8, 2014 to correct the building construction type.

SUMMARY

Shortly after midnight on Sunday, April 12, 2009, a 30-year old male career probationary fire fighter and a 50-year old male career captain were killed when they were trapped by rapid fire progression in a wind-driven residential structure fire. The victims were members of the first arriving company and initiated fast attack offensive interior operations through the front entrance. Less than six minutes after arriving on-scene, the victims became disoriented as high winds pushed the rapidly growing fire through the den and living room areas where interior crews were operating. Seven other fire fighters were driven from the structure but the two victims were unable to escape. Rescue operations were immediately initiated but had to be suspended as conditions deteriorated. The victims were located and removed from the structure approximately 40 minutes after they arrived on location.

Key contributing factors identified in this investigation include: an inadequate size-up prior to committing to tactical operations; lack of understanding of fire behavior and fire dynamics; fire in a void space burning in a ventilation controlled regime; high winds; uncoordinated tactical operations, in particular fire control and tactical ventilation; failure to protect the means of egress with a backup hose line; inadequate fireground communications; and failure to react appropriately to deteriorating conditions.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that an adequate initial size-up and risk assessment of the incident scene is conducted before beginning interior fire fighting operations

- ensure that fire fighters and officers have a sound understanding of fire behavior and the ability to recognize indicators of fire development and the potential for extreme fire behavior (such as smoke color, velocity, density, visible fire, heat)

- ensure that fire fighters are trained to recognize the potential impact of windy conditions on fire behavior and implement appropriate tactics to mitigate the potential hazards of wind-driven fire

- ensure that fire fighters understand the influence of ventilation on fire behavior and effectively apply ventilation and fire control tactics in a coordinated manner

- ensure that fire fighters and officers understand the capabilities and limitations of thermal imaging cameras (TIC) and that a TIC is used as part of the size-up process

- ensure that fire fighters are trained to check for fire in overhead voids upon entry and as charged hoselines are advanced

- develop, implement and enforce a detailed Mayday Doctrine to insure that fire fighters can effectively declare a Mayday

- ensure fire fighters are trained in fireground survival procedures

- ensure all fire fighters on the fire ground are equipped with radios capable of communicating with the Incident Commander and Dispatch

Additionally, research and standard setting organizations should:

- conduct research to more fully characterize the thermal performance of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) facepiece lens materials and other personal protective equipment (PPE) components to ensure SCBA and PPE provide an appropriate level of protection.

Although there is no evidence that the following recommendation could have specifically prevented the fatalities, NIOSH investigators recommend that fire departments:

- ensure that all fire fighters recognize the capabilities and limitations of their personal protective equipment when operating in high temperature environments.

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after midnight on Sunday, April 12, 2009, a 30-year old male career probationary fire fighter (Victim # 1) and a 50-year old career fire captain (Victim # 2), members of Engine 26, the first-arriving engine company, were killed when they were trapped by rapid fire progression inside a 4,200 square-foot residential structure. On April 13, 2009, the fire department contacted the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Division of Safety Research, Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program and requested an investigation of the incident. The same day, the U. S. Fire Administration notified NIOSH of this incident. On April 15th, a NIOSH Safety Engineer traveled to Texas and met with representatives of the fire department, the State Fire Marshals Office, and two representatives of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to inspect and map the residential structure where the fatalities occurred. Note: NIST was requested by the fire department to develop a computerized fire model of the incident. On April 23rd, the NIOSH Safety Engineer and two Occupational Safety and Health Specialists returned to Texas to investigate the fatalities. Meetings were conducted with representatives of the fire department, the International Association of Fire Fighters union local, the State Fire Marshals Office and city arson investigators. Interviews were conducted with the fire fighters and officers involved in the incident. The two victims turnout clothing, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), and personal protective equipment worn at the time of the incident were inspected and photographed. The SCBA and personal alert safety system (PASS) devices were sent to the NIOSH National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory for further evaluation. NIOSH investigators reviewed the fire departments standard operating procedures and training requirements, as well as the training records of the two victims and the incident commander. The investigators reviewed incident scene photographs and video, fire ground dispatch audio records, SCBA and personal protective equipment (PPE) inspection and test records, fire apparatus test records and discussed the layout and construction features of the structure with the home-owners family members.

FIRE DEPARTMENT

The career fire department involved in this incident serves a metropolitan population of approximately 2.2 million residents and a total day-time population of more than 3 million in an area of approximately 618 square miles. The fire department had 3,605 uniformed fire personnel at the time of the incident. The fire department operates a total of 262 fire apparatus including 86 engines, 37 ladder trucks (including 6 tower ladders), 12 booster engines, 57 ambulances (basic life support services with 2 emergency medical technicians (EMTs) per ambulance), 27 medic units (with 1 paramedic and an EMT), 19 squad units (with 2 paramedics assigned), 18 airport rescue fire apparatus, 10 evacuation boats, 10 inflatable rescue boats, and 6 personal watercraft. The fire department operates 2 rescue units and 1 heavy rescue unit plus 3 Hazardous Materials (HazMat) units. During 2008, the fire department responded to 593,696 total runs that included 211,950 fire responses and 381,746 EMS responses. The 211,950 fire responses included 48,256 fire events.

The department maintains well-documented written procedures covering items such as training, incident management, fire suppression operations, accountability, Mayday, rapid-intervention team (RIT) operations, thermal imaging camera (TIC) usage, and rescue operations. Initial alarm assignments to structure fires include three engine companies, two ladder companies, one ambulance, one medic unit, and two district chiefs. The department typically employs fast attack offensive operations at structure fires. Generally, fast attack/offensive operations at this department involve the first arriving engine company attacking the fire with a hoseline charged with the engines tank water while water supply is being established. The first-in engine company also searches for victims in the immediate area. The first arriving ladder company initiates ventilation procedures. The second-in engine company pulls a second hoseline to back up the first engine company. The second-in ladder company assists the first-in engine company with search and rescue operations. The third engine company is assigned to rapid intervention team (RIT) operations. Other arriving units are assigned to assist with establishing water supply, back-up the initial engine company, search and rescue, RIT operations, assist with accountability and other duties as designated by the incident commander.

Since 2000, the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program has conducted four traumatic and one medical fire fighter line-of-duty death investigations at this department, prior to this incident.1-5 A second medical line-of-duty death is currently under investigation (F2009-17). Each of these previous traumatic fire fighter fatality investigations involved members of the first arriving company who died during interior fire suppression operations.

TRAINING and EXPERIENCE

The state of Texas requires 640 total hours of training for a fire fighter to receive Texas Fire Fighter certification. The fire department involved in this incident requires potential candidates for employment as a fire fighter to have a high school diploma or GED and 60 hours of college credit, or an honorable discharge from the military in addition to Texas Fire Fighter certification before they are admitted to the citys fire academy.

The fire departments recruit class curriculum includes an overview of radio operations and use in a classroom setting; rapid intervention team (RIT) and Mayday procedures while dressed in full bunker gear in a classroom setting, and radio use incorporated into burn building training. The burn building training includes hands on exercises in which the recruits enter the burn building in full bunker gear and perform a number of tasks that require radio communication with the training officer outside the burn building. These exercises include emergency scenarios requiring the recruits to radio Mayday.

Victim # 1 had been employed at the fire department less than one year and was a probationary fire fighter. He had received Basic Fire Fighter certification from the fire department training center and was also a certified emergency medical technician (EMT). He had previously served for 9 years in the U.S. Army.

Victim # 2 had been employed at the fire department for approximately 30 years and had received numerous training such as Basic Fire Fighter certification, engine company operations, pumper operations, high-rise firefighting, search line / tag line, roadway incident operations, ventilating metal deck roofs, radiological monitoring, electronic accountability system operation, crew resource management, medical issues, MRSA, and forcible entry. The bulk of this training included hands-on training provided by the fire department. He had completed 37 hours of fire department sponsored training in 2008 and 20 hours in 2009. He had previously completed several college credits and had been a captain since 2004. He had also been a certified Fire Service Instructor since 2004.

The Engine 26 engineer / operator (E/O) had been employed at the fire department for approximately 30 years and had been an E/O since the early 1990s. He was normally assigned to another station as an E/O on a ladder company. He was working a debit daya shift at Station 26 at the time of the incident. He had been trained and had experience as an engine company E/O but was not experienced with the type of engine operated at the time of the incident.

The Incident Commander had been employed at the fire department for approximately 36 years and had completed numerous training sponsored by the fire department including 38 hours in 2008 and 14 hours in 2009 at the time of the incident. He had been a district chief since 1992.

a Most fire fighters work a schedule requiring that one day each month, an extra shift must be worked so that the number of hours worked equals the number of hours paid. These extra shifts are referred to as a debit day and the fire fighter may be assigned to work outside their normal assignment during the debit day.

EQUIPMENT and PERSONNEL

The fire department dispatched three engine companies, two ladder companies, two district chiefs, and an ambulance crew on the first alarm assignment. Note: Some district chiefs are assigned an Incident Command Technician (ICT) who is a fire fighter that assists the district chief with a number of duties including assisting at the command post during major incidents. In this incident, the district chief who became the incident commander did not have an ICT assigned to him. Also, a safety officer is not routinely dispatched to first alarm residential structure fires. Table 1 identifies the apparatus and staff dispatched on the first alarm, along with their approximate arrival times on-scene (rounded to the nearest minute).

After arriving on-scene and sizing up the structure, District Chief 26 assumed Incident Command (IC) and requested upgrading the incident to a 1-11 assignment at approximately 0021 hours which resulted in the following additional units being dispatched:

- District Chief 46 with an ICT

- Engine 23 – Captain, Engineer / Operator, 2 fire fighters.

Once fire fighters were determined to be missing, the IC requested a 2-11 assignment at approximately 0026 hours. Additional resources were dispatched, including 4 engine companies, 2 ladder companies, 2 district chiefs, 1 rescue unit, 1 safety officer, 1 cascade unit, 1 rehab unit, 1 tower unit, a communications van, an ambulance supervisor and the shift commander. The units directly involved in the search and recovery operations for the two missing fire fighters included:

- Engine 35 – Acting Captain, Engineer / Operator, 2 fire fighters

- Engine 40 – Captain, Engineer / Operator, 2 fire fighters

- Engine 61 – Captain, Engineer / Operator, 2 fire fighters.

TIMELINE

See Appendix 1 for a timeline of events that occurred as the incident evolved, such as dispatch, arrival of companies, sentinel communications and tactical actions. The timeline also contains reference to changes in the ventilation profile and indicators of critical fire behavior. Note: Not all events are included in this timeline. The times are approximate and were obtained by studying the dispatch records, witness statements, and other available information. In most cases, the times are rounded to the nearest minute.

Table 1. First Alarm Equipment and Personnel Dispatched

| Resource Designation | Staffing | On-Scene (rounded to minute) |

|---|---|---|

| Engine 26 (E-26) |

Captain (Victim # 2) |

0013 hrs

|

| District Chief 26 (DC-26) |

District Chief

|

0014 hrs

|

| Ladder 26 (L-26) |

Captain |

0014 hrs

|

| Ambulance 26 (A-26) |

2 Fire fighters

|

0015 hrs

|

| Engine 36 (E-36) |

Captain |

0015 hrs

|

| Engine 29 (E-29) |

Captain |

0016 hrs

|

| Ladder 29 (L-29) |

Captain |

0016 hrs

|

| Medic 29 |

Engineer / operator |

0016 hrs

|

| District Chief 23 (DC-23) |

District Chief |

0018 hrs

|

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT

At the time of the incident, each fire fighter entering the structure was wearing their full ensemble of personal protective clothing and equipment, consisting of turnout gear (coats, pants, and Reed Hood (issued by this fire department and constructed of the same material as the turnout coat/pant ensemble)), helmet, gloves, boots, and a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). The Reed Hood is a two-layer hood constructed to the fire departments specifications. The Reed Hood is worn to provide an extra layer of thermal protection to the head and neck and is certified to meet the requirements of NFPA 1971 Standard on Protective Ensembles for Structural Fire Fighting and Proximity Fire Fighting (2007 Edition).6

Each fire fighters SCBA contained an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) device. In addition, a redundant system (TPASS) was also in use and worn by each fire fighter at the incident. This stand-alone TPASS (meeting the requirements of NFPA 1982 Standard on Personal Alert Safety Systems (PASS), 2007 Edition) 7 transmits a continuous radio signal to a base receiver that is maintained and monitored in the district chiefs vehicle at the command post. This stand-alone TPASS is a crucial component of the fire departments electronic accountability system on the fireground. The base receiver provides an audible and visual status of each fire fighter on the fireground. When the TPASS is activated, either by lack of motion or manual activation by the user, an emergency warning signal is sent to the base receiver indicating the existence of an emergency. This system identifies each crew member by apparatus number and riding position. Note: The officer is designated position A, the fire fighter riding behind the officer is designated position B, the fire fighter behind the engineer / operator (E/O) is position C and the E/O is position D. In this incident, the base receiver at the command post received alarms from E-26 C (when E-26 fire fighter 2 adjusted his helmet), E-26 A (Victim # 2) and E-26 B (Victim # 1). An evacuation signal can be transmitted from the base receiver to all TPASS devices where a distinct audible alarm alerts fire fighters to exit the structure or incident scene. Fire fighters manually reset their unit, acknowledging to the base receiver that the fire fighter has received the evacuation signal.

This department issues portable hand-held radios to all fire fighters by assigning radios to each apparatus riding position. After the incident, the Engine 26 captains (Victim # 2) radio was found on the apparatus and Victim #1s radio was found on his body turned off and on the dispatch channel (TAC 4).

Following the inspection by NIOSH investigators, the SCBA worn and used by both victims were sent to the NIOSH National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) for additional evaluation. The SCBA worn and used by both victims were too badly damaged by fire and heat exposure to be tested. Both SCBA facepiece lenses were melted with holes penetrating the lens material. The integrated PASS device on the SCBA used by Victim # 1 was operational. The integrated PASS device on the SCBA used by Victim # 2 did not function during the NPPTL inspection. The performance of the SCBA used by both victims does not appear to have been a contributing factor in this incident. The fire conditions encountered by the victims possibly exceeded the thermal resistivity of the SCBA. The SCBA evaluation report summary can be found in Appendix Two. Note: Rescuers reported hearing the sound of a PASS device which drew them to the location of Victim # 1. It was not clear whether or not rescuers heard the PASS device used by Victim # 2.

STRUCTURE

The structure involved in this incident was a one-story ranch-style residential structure of Type III ordinary construction. The structure consisted of traditional wood framing with a brick veneer exterior and contained approximately 4,200 square feet of living space. The original structure was built in the late 1950s with multiple improvements and additions to the property including an in-ground pool, a pool house, a detached apartment building and an electrical-generating wind mill approximately 40 feet high. The wind mill had been non-functional for approximately the previous 10 years but heavy-gauge, three-phase copper wiring used as part of the electrical service entrance ran through the concealed attic space along the length of the structure. Some of the renovation work included the addition of a vaulted ceiling and skylights added over the master bedroom and bathroom areas along with the addition of an exercise room and office area at the rear (Side C). All exterior walls were brick. A glass atrium was also added that enclosed a patio at the rear of the family room or den (see Photo 1). At the time of the fire, the structure measured approximately 109 feet across the front (Side-A) and 54 feet across Side-D. Most of the doors and windows (except for the glass atrium) were protected by metal burglar bars. While the structure was severely damaged by the fire, evidence suggested that some of this renovation work resulted in a double roof at the rear (C D corner) of the structure. The double roof produced a void space with fuel (asphalt shingles, framing lumber, sheeting, etc.). Note: Void spaces can create hazards for fire fighters, especially void spaces that contain high fuel loads (exposed framing lumber and wood products) and high energy fuels (asphalt roofing shingles, plastic pipe, insulation on wiring, etc.). Fires in roof voids and other compartments with limited ventilation generally progress to a ventilation-controlled burning regime.8 This hazard was identified in a previous NIOSH report F2007-29.9

|

|

Photo 1. Photo shows remains of glass atrium at C-side of structure. The glass atrium was added to enclose a patio at the rear of the family room. Failure of one or more windows on the C-side would have opened a path for wind blowing from the southeast to penetrate the living area. |

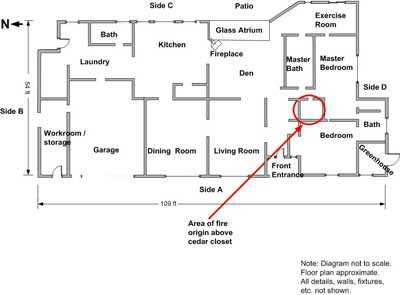

The citys fire / arson investigators determined that the fire was accidental in nature and originated in the electrical wiring above a hallway closet near the master bedroom (see Diagram 1 and Diagram 2). The closet ceiling light was controlled by a switch that automatically turned the light on when the door was opened. Reportedly, the door was left open and one of the homeowners smelled smoke so the couple left the house via the garage door, leaving the front entrance door locked and the garage door open.

The size and layout of the property presented a number of challenges to quickly conducting a full 360-degree size-up of the incident site. Chain link fences on both the B and D-sides extended from the edges of the structure to enclose the pool and patio areas located to the left (B-side) and rear (C-side) of the house. A brick and masonry wall approximately waist high also extended out from the A-D corner that separated the residence from the adjoining property. The house sat at the top of a steep embankment supported by a retaining wall. Immediately behind the rear patio and deck, the embankment dropped almost straight down approximately 11 feet to the bottom of the retaining wall where the back yard sloped downward for several more feet. The brick wall along the D-side and the chain link fence enclosing the pool and patio areas restricted access from the sides and rear (see Photos 2, 3, and 4). During the incident, the chain link fences at both sides were breached.

The property was bordered to the rear by a small pond and marsh that extended into a bayou located to the southeast (see Diagram 3).

|

|

Diagram 1. Satellite view of property showing approximate location of fire origin and where L-26 crew vented the roof. Also note the approximate origin of the fire. The objects within the highlighted oval are believed to be the roof vent and sky light where fire fighters observed flames showing above the roofline early into the event. |

|

|

Diagram 2 |

|

|

Photo 2. Photo taken from the A-D corner of the fire structure shows how access to the D-side of the structure was limited by the masonry wall. |

|

|

Photo 3. Photo taken from rear of structure standing in back yard shows how access to the C-side of the structure was limited by the location |

|

|

Photo 4. Photo taken from A-B corner in front of structure shows how access to B-side of structure was limited by the masonry and |

|

|

Diagram 3 |

WEATHER

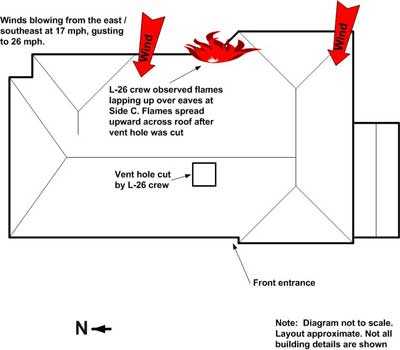

High winds may have been a contributing factor in this incident. At the time of the fire, weather conditions in the area included a temperature of 69 degrees Fahrenheit (21 degrees Celsius), 68 to 75 percent relative humidity, with sustained winds from the east / south-east at 17 miles per hour (mph) (27 km/hr) gusting to 26 mph (42 km/hr).10 Fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH investigators reported changing winds during the incident. At times, smoke blew across the street obstructing vision in front of the fire structure. Wind from the east / southeast was blowing against Side-C of the structure, increasing the air pressure on Side-C in relation to Side-A. After crews opened the front door, any failure of windows or self ventilation on Side C would have provided a flow path for hot gases and flames to be pushed by wind from Side C through the entrance on Side-A (see Photo 1 and Diagram 4). Research by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has shown wind speeds on the order of 10 to 20 mph (16 to 32 km/hr) are sufficient to create wind-driven fire conditions in a structure with an uncontrolled flow path.11

|

|

Diagram 4. Approximate location of roof vent hole cut by L-26 crew. |

INVESTIGATION

Shortly after midnight on Sunday, April 12, 2009, just before 0008 hours, the municipal 911 dispatch center received a phone call reporting a residential structure fire. The caller initially stated someone was still inside, and then stated that both residents were outside the residence. At 0008 hours a first alarm dispatch was sounded. District Chief 26 (DC-26), Engine 26 (E-26), Ladder 26 (L-26), Engine 36 (E-36), Engine 29 (E-29), Ladder 29 (L-29), Ambulance 26 (A-26), Medic 29 (M-29) and District Chief 23 (DC-23) were dispatched. All units marked enroute between 0009 and 0010 hours.

Responding crews observed smoke and could smell smoke as they approached the residential structure located on a twisting cul-de-sac. The first arriving crews encountered severely limited visibility due to the heavy layer of thick (optically dense) dark smoke blowing from east to west across the street. E-26 arrived first on-scene at approximately 0013 hours. The E-26 engineer / operator (E/O) and captain (Victim # 2) discussed the difficulty in determining which house was on fire as E-26 approached the scene. The E-26 E/O was not the regular E/O with this crew and was unfamiliar with the area. Due to the limited visibility, he was concerned about hitting bystanders who were waving at the arriving apparatus to direct them to the burning home. Engine 26 was positioned just past the front door. The E-26 E/O reported that visibility improved after E-26 passed the front door. A water hydrant on a dead-end main was located on the officers side of E-26 just a few feet away. The E-26 captain radioed that heavy smoke was coming from a one-story wood-frame residential structure and stated he was making a fast attack. District Chief 26 arrived on-scene immediately behind E-26 and radioed that he was assuming Incident Command (IC) at 0014 hours. The IC staged his vehicle on the side of the street, allowing room for Ladder 26 to drive past his location to stage behind E-26 (see Diagram 1 and Diagram 5). L-26 arrived on-scene a few seconds later and radioed that they would be venting the roof. The L-26 captain reported observing fire at what he described as a turbine vent near the peak of the roof. Engine 36 arrived next just before 0015 hours. The IC radioed that accountability (electronic accountability system) was in place before 0016 hours.

The E-26 probationary fire fighter (Victim # 1) started to pull a pre-connected hand line from the officers side of the apparatus, then was instructed to pull a pre-connect from the drivers side. After determining which house was on fire, Victim # 1 and the E-26 fire fighter # 2 (riding in position C) pulled the 1 3/4-inch pre-connected hand line (200 feet in length) to the front door. The E-26 fire fighter # 2 also carried a TNT tool. The E-26 captain (Victim # 2) arrived at the front door with a pry bar and the captain and fire fighter # 2 forced open the steel security bars and punched the lock out of the front door. The E-26 captain kicked open the front door and the crew observed heavy (optically dense) smoke and heat just inside the doorway. Note: Following the incident, the E-26 captains thermal imaging camera (TIC) was found lying on the ground outside the structure near the front door.

The L-26 captain immediately sized-up the structure from the front yard and instructed his crew that they were going to vent the roof. The L-26 crew quickly gathered two 16-foot ladders, two powered rotary saws and an 8-foot pike pole. A ground ladder was spotted immediately to the left of the sidewalk leading to the front door. The L-26 captain and an L-26 fire fighter climbed to the roof. The second L-26 fire fighter climbed to the top of the ladder and served as a spotter for the fire fighters working on the roof.

E-36 arrived on scene just before 0015 hours. The E-36 crew was instructed by the IC to advance a back-up line to support the E-26 crew. The E-36 E/O was instructed to skull-drag (drag by hand) a four-inch supply line from E-26 to the hydrant and assist the E-26 E/O in establishing water supply to E-26. The E-36 fire fighters pulled a second 200-foot length of 1 ¾-inch preconnected hand line from the drivers side of E-26 to the front door. The E-36 captain observed the E-26 crew getting ready to make entry and waved to the E-26 captain standing at the front entrance, indicating the E-36 crew would be right behind the E-26 crew.

|

|

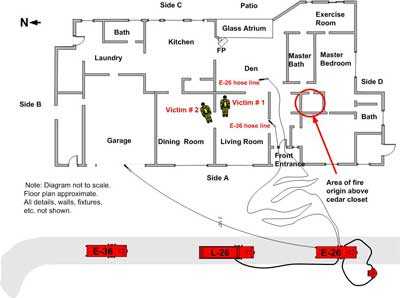

Diagram 5. Diagram shows location of initial attack lines and locations where victims were found. |

E-29 arrived on-scene just before 0016 hours. L-29 arrived on-scene and was assigned by the IC to assist the E-26 crew with an interior primary search at approximately 0016 hours. E-29 was assigned to Rapid Intervention Team (RIT) operations. DC-23 arrived on-scene at approximately 0018 hours and the IC assigned him to assume Sector A Command, responsible for interior operations. The IC instructed him to size up the scene and to advise the IC on whether to continue offensive operations or to switch to a defensive mode. Note: DC-23 was assigned a chiefs aide, known as an incident command technician (ICT). Upon arrival on-scene, DC-23s vehicle was staged behind the other emergency vehicles. DC-23 was assigned to Sector A Command and his ICT assisted the IC at the command post.

The E-26 crew initially waited at the front door, then advanced the hose line into the house, standing up, while waiting for the hose line to be charged. The E-26 probationary fire fighter (Victim # 1) carried the nozzle followed closely by the E-26 captain (Victim # 2). The E-26 E/O supplied water to the hose line when he saw the crew begin entering the front door (his view was restricted due to the optically dense smoke). As the crew advanced down the hallway, they encountered a piece of furniture or fallen debris that was blocking their advance. This object was passed back to the E-26 fire fighter # 2 (E-26C) who threw it outside. He then re-entered the structure and fed hose through the doorway as the E-26 captain and probationary fire fighter advanced the hose line down the hallway into the structure. Soon after, the E-36 crew entered the structure through the front door. The E-26 fire fighter # 2 experienced a problem when his helmet was dislodged as the E-36 crew passed by. He informed his captain that he needed to back out to adjust his helmet. The fire fighter stepped outside and while adjusting his helmet strap, his TPASS system went into alarm and had to be reset.b The hose line was initially charged with tank water while water supply was being established. Note: When A-26 arrived on-scene, the driver assisted the E-26 and E-36 engineer / operators in dragging supply lines to establish water supply while the A-26 EMT reported to the command post to set up and operate the TPASS accountability system. The A-26 driver was working an overtime shift and was normally assigned as an E/O on an engine company at another station. The E-26 E/O received assistance from the E-36 E/O and the A-26 driver in operating the pump and establishing the proper discharge pressures on the hose lines. After adjusting his helmet, the E-26 fire fighter # 2 (E-26C) re-entered the structure but could not locate the E-26 crew as other crews had entered the hallway in front of him.

b Manually resetting the TPASS system requires the user to push a button on the device.

The L-26 captain observed fire coming from a roof vent that was located on the back side of the roof and near the ridge line between the front door and D-side of the house. Note: This may have been a vent or skylight over the master bathroom. The L-26 captain surveyed the roof as an L-26 fire fighter began to cut a ventilation hole on the front side of the roof located above and to left of the front door. Fire was observed coming though the cut just behind the saw. The L-26 captain also observed a small amount of fire (approximately 1-2 feet wide) lapping up over the eave at the back (C-Side) of the roof below him (see Diagram 4). As the ventilation cuts were being finished, the IC radioed the L-26 captain to ask for a status report on the roof ventilation activities at approximately 0019 hours. The L-26 captain replied he was punching it right now then used the pike pole to pry up the roof decking and punched down with the pike pole twice, penetrating the ceiling both times. The IC also radioed E-26 for a progress report at 0019 hours but did not receive a response. Large flames erupted from the vent hole, forming a swirling vortex of fire extending several feet into the air. The L-26 captain looked toward the back side of the roof and observed that the flames lapping up over the eaves had now spread to be over 20 feet wide. He also observed that flames were racing across the surface of the roof right toward the L-26 crew. Note: The L-26 captain described the flames as flowing across the surface of the roof. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is thermal radiation from the plume of smoke, hot gases and fire erupting from the vent hole radiating energy down to the roof and pyrolyzing the asphalt shingles. Convective currents created by the rising smoke and winds could have mixed the pyrolysis products with air, creating a flammable mixture that burned as the wind currents moved the flammable mixture across the surface of the roof. The observed phenomenon was an indicator of the amount of heat energy being generated by the fire. After exiting the roof, the L-26 crew moved to the D-side of the structure to do a 360-degree walk-around size-up, but their attempt was stopped by the masonry and chain link fences separating the structure from the adjoining property.

The E-36 crew advanced the second 1 ¾-inch hand line through the doorway just as the Ladder 26 crew was finishing the ventilation cuts on the roof (the E-36 captain reported he could hear the sound of the ventilation saw running as the E-36 crew made entry). A E-36 fire fighter carried the nozzle, followed by the E-36 captain and the other E-36 fire fighter. The E-36 captain reported that he had to crouch down to see under the smoke layer and he attempted to use his thermal imaging camera (TIC) to search for fire but the smoke was so thick in the hallway that the captain could not see the TICs screen right in front of his facepiece. The E-36 captain reported that as he crouched down to peer under the smoke, he could see the legs of the E-26 crew 5 or 6 feet in front of him (possibly standing upright), just before they disappeared into the smoke. The E-36 crew advanced 10 to 15 feet down the hallway when the captain began pulling ceiling in the hallway with a pike pole that was carried into the structure by an E-36 fire fighter. The E-36 fire fighter with the nozzle informed the captain that the hose line had just been charged (from E-26 tank water) as the captain continued to pull ceiling. Suddenly, intense heat forced the E-36 crew to the floor and the E-36 fire fighter with the nozzle opened the nozzle and began flowing water through the hole in the ceiling. Note: One of the E-36 crew members reported seeing a red glow in the attic overhead as the ceiling was being pulled. Water flowed from the nozzle, then the pressure in the hose line dropped, disrupting the water flow as the hose went limp. When the fire fighter closed the nozzle, the pressure in the hose line increased but as soon as the nozzle was opened, the water pressure would drop off. The temperature continued to increase and the E-36 captain reported hearing a loud whooshing or roaring sound as the crew backed down the hallway toward Side A. As the E-36 fire fighter with the nozzle backed up, he came to the doorway to his left that led into the living room. He observed fire overhead, behind him and to his left, with an orange glow that reached almost to the floor. The E-36 captain reported hearing another loud whooshing or roaring sound behind the crew. At this point, the E-36 crew advanced a few feet into the living room where fire continued to burn overhead and the heat continued to intensify. Water flowing from their hoseline did not appear to have much effect on the fire.

The L-29 crew was assigned to assist E-26 in a primary search so they proceeded to the front door to make entry. The L-29 captain was first to enter the doorway following a hoseline that led through the door and went straight down the hallway. The L-29 crew (captain and two fire fighters) immediately felt the heat at the doorway and had to drop down and crawl into the house. The conditions worsened as they advanced along the hoseline into the house. The crew had to stop to move debris out of the way (possibly a board that had dropped down) that was blocking their path. The L-29 captain reported that at one point, he briefly saw legs of fire fighters in front of him (either the E-26 or E-36 crew) and he also reported that he knew the hoseline was being advanced. Note: Both L-29 and E-36 crew members reported briefly bumping into other fire fighters in the hallway. This may have occurred as the E-36 crew was retreating from the hallway into the living room and the L-29 crew was advancing into the hallway.

The L-29 captain reported that he attempted to use his thermal imaging camera but the view on the screen was obscured by the high heat readings. The L-29 crew could hear a crew (probably the E-36 crew) flowing water in the living room to their left. The L-29 captain observed that the hoseline he was following was no longer being advanced. He also reported the smoke layer dropping almost to floor level as they followed the hoseline. As the L-29 crew advanced, the captain came to the closed nozzle lying on the floor with no other fire fighters around. The L-29 captain reported the room was fully involved at this point. The L-29 captain began to work the nozzle overhead and side to side. He began to feel heat behind him and turned to observe fire blowing out a doorway to his left (possibly the doorway from the den to the living room see Diagram 5). The L-29 crew pulled the nozzle back to the doorway. The L-29 captain continued to work the nozzle until he heard the IC radio to go defensive. Note: The L-29 captain reported that the fire conditions were growing worse and the water was not effective in knocking down the fire. He also reported he appeared to have good water pressure up to this point. As the L-29 crew backed down the hallway, they encountered the E-36 crew coming from the living room (to their left) and both crews exited the house through the front door. Note: The rapidly deteriorating conditions, observed by both the E-36 and L-29 crews, possibly made worse by high wind conditions, may have caused the E-26 captain and fire fighter to become disoriented.

At approximately 0021 hours, the IC radioed Sector A Command and asked if the crews needed to pull out. At approximately 0021 hours, the IC radioed Sector A Command and asked for an update on the interior conditions. Note: At approximately this time, the incident was upgraded to a 1-11 incident. Engine 23 and a third district chief (District Chief 46) were dispatched for additional resources. Sector A Command observed heavy fire swirling from the roof ventilation hole and no other signs of any progress being made on the interior attack so he radioed the IC that they should switch to a defensive mode. At approximately 0022 hours, the IC radioed dispatch of the change to defensive operations, requested a personal accountability report (PAR) from all crews and instructed all E/Os to sound the evacuation signal using their air horns. An evacuation signal was also sent through the TPASS system. The Sector A Chief observed fire fighters exiting the front doorway and observed that some looked like they had taken a beating. He also observed 2 fire fighters exit with their helmets on fire.

The PAR indicated that all fire fighters were accounted for except the two E-26 crew members. The E-26 fire fighter # 2 (who had exited the structure to adjust his helmet) reported to the Sector A Chief that his crew had not yet come out of the structure. The Sector A Chief radioed to the IC that two E-26 crew members were missing. At approximately 0024 hours, the IC activated the RIT Team to search for the missing E-26 crew members. He also advised dispatch to assign the incident as a 2-11 fire. Note: The 2-11 assignment dispatched several additional companies including Engine 35 (E-35), Engine 40 (E-40), Engine 61 (E-61), Engine 18 (E-18), Rescue 42, and two District Chiefs (DC-8 and DC-70) for additional resources. At approximately 0025 hours, dispatch asked the IC if he wanted a Mayday declared for the E-26 crew. The IC confirmed the Mayday and advised dispatch that the RIT Team was being activated as the TPASS system was showing an emergency alarm for E-26 A and E-26 B.

The Rapid Intervention Team (RIT) (E-29 captain and 2 fire fighters) was staged in the front yard near the street. They asked for a dry 1 ¾-inch hand line lying in the front yard (pulled off E-26) to be charged so they could enter the structure but the E-26 E/O told them that based on the engines residual pump pressure, he didnt have enough pressure to charge another line. The RIT picked up the 1 ¾-inch line that the E-36 crew had pulled out and attempted to enter the front door. This hand line did not have much pressure and the RIT captain advised the Sector A Chief that they didnt have any water pressure. While at the front door, windows to the left of the door self-vented and fire began to roll out the windows and lap up over the eave. The RIT captains turnout coat started to catch fire and his crew members had to pat him down to extinguish the fire on his coat. Note: The RIT captain was standing near the front doorway and likely under the roof overhang. All PPE examined by the NIOSH investigators was NFPA-compliant so the fire observed on his turnout coat may have resulted from burning debris dropping from the burning overhang or possibly the roof itself (liquefied asphalt material in the roof shingles dripping down). It was also reported that the RIT captains SCBA harness strap was on fire. The RIT was not able to make entry due to the fire conditions. At approximately 0028 hours, the Sector A Chief requested another PAR and all crews were accounted for except the two missing E-26 crew members.

At approximately 0030 hours, the IC instructed the L-26 crew to set up the ladder pipe for master-stream operations. The Sector A Chief directed the operation of the ladder pipe and assigned the RIT (E-29 crew) to take a hand line to the D-side of the structure. The E-29 crew took the uncharged 1 ¾-inch hand line to the D-side and waited several minutes before the hoseline was pressurized. Note: Water supply consisted of two 4-inch supply lines running from the hydrant to E-26 and a single 4-inch supply line running from E-26 to L-26 to supply the ladder pipe for master stream operations. The hose line was eventually charged and the E-29 crew worked at the D-side fighting fire and protecting the adjacent house.

As the ladder pipe was being set up, the L-26 captain and a L-26 fire fighter crawled in the front door following the hoseline. The captain used his thermal imaging camera (TIC) to scan the area in an attempt to locate the missing fire fighters but the interior conditions were so hot that the image on the TIC screen turned white. They advanced further down the hallway a few feet with fire rolling above and behind them. They backed out, the captain briefly discussed the interior conditions with the Sector A Chief, and then the L-26 crew members crawled in the front door a second time. The master-stream began to knock debris down around them and they had to back out to the outside.

After the change to defensive operations, the L-29 crew was assigned to take a 2 ½-inch hand line to the garage door. The crews had to wear their SCBA while operating hand lines from the exterior. Fire fighters worked the master-stream and exterior hand lines for approximately 15 minutes knocking down the heavy fire conditions. District Chief 46 arrived on-scene at approximately 0035 and was assigned as Sector C Chief with the E-29 crew assigned to him. Due to the fences and layout of the property, they could not walk to the rear of the structure so the Sector C Chief reported back to the front of the house. Note: At some point, the E-29 crew breeched the chain-link fence to gain better access to the D-side. Engine 35 and Engine 40 arrived on-scene and were assigned to report to Sector A and standby for rescue operations. Additional companies arrived on-scene and E-35, E-40, Engine 61 and Rescue 42 crews were assigned to report to District Chief 46 at the front of the structure. The Sector A Chief advised the IC that part of the roof had burned off and the structure had been weakened, but crews were preparing to go offensive to search for the missing fire fighters.

At approximately 0046 hours, the Sector A Chief advised the IC that the conditions had improved enough for crews to go back inside and resume search and rescue operations. The IC instructed L-26 to shut down the master-stream and crews were assigned to enter the front door. The Sector A Chief advised the IC that he was now Interior Command. The E-61 crew entered the front door and started a left hand search through the living room area. As they passed the front living room window, the crew heard a TPASS alarm across the room to their right. At approximately 0051 hours, the E-61 crew located the E-26 probationary fire fighter (Victim # 1) in the living room near the doorway to the dining room. Victim # 1 was found on his knees slumped over a piece of furniture, covered with a small amount of debris (see Diagram 5 and Photo 5). His facepiece was on. The E-35 crew pulled a 1 ¾-inch hand line off E-36 and advanced the hose line through the front door. They also proceeded to their left and heard radio traffic that Victim # 1 had been located. The E-35 crew entered the dining room and observed reflective trim on the turnout clothing worn by the E-26 Captain (Victim # 2). At 0052 hours, Interior Command radioed the IC that both missing fire fighters had been found. The E-26 Captain (Victim # 2) was found just inside the dining room doorway (see Diagram 5 and Photo 6). The E-26 Captain was found lying face down with his facepiece on. It was unclear as to whether rescuers heard a PASS device on Victim # 2 or not, but the TPASS base unit did receive an emergency alarm from both victims. Both victims were pronounced dead at the scene.

Following the incident, the fire department conducted pump tests on E-26 and evaluated the hydrant pressure at the hydrant E-26 was connected to. The E-26 pumps were found operational. The hydrant static pressure and flow rate were found to be within their normal ranges. The cause of the water pressure problems experienced by the different hose lines was never determined.

|

|

Photo 5. Photo shows location where Victim # 1 was located in living room. The middle tool marks location where victim was found slumped against the chair at top of photo. Note that the upholstery on the chair is not burned, indicating that a flashover did not occur in this area. |

|

|

Photo 6. Photo shows location where Victim # 2 was located in dining room just through doorway separating the dining room from the living room. |

FIRE BEHAVIOR

According to the arson investigators report, the fire originated in the electrical wiring above a hallway closet near the master bedroom and was accidental in nature (see Diagram 2). It is unknown how long the fire burned before the residents observed fire in the closet and exited the structure.

The developing fire burning in the void space produced a large volume of fuel-rich excess pyrolizate and unburned products of incomplete combustion. First arriving companies observed optically-dense thick dark smoke from a one-story residential dwelling being pushed by sustained winds across the street (from east to west). The smoke obscured visibility in the street, making it difficult to determine which structure was on fire. The roof ventilation crew observed flames coming from a roof-mounted vent and a small amount of fire lapping up over the eave at the C-side (rear). Fire emitted from the saw kerf as the ventilation crew cut the roof opening. Moments after the roof was vented, the fire conditions changed drastically as the fuel-rich smoke and fire gases ignited. The carpet and furniture upholstery in the living and dining rooms (where the victims were found), were unburned, indicating that a flashover did not occur in those areas. Other areas of the house were more heavily damaged (i.e. master bedroom, bath, exercise room) by the fire that continued to burn after the fatalities occurred. Note: Conditions can vary considerably from compartment to compartment and flashover can occur in areas other than living spaces (e.g., roof voids).12 It is likely that a ventilation induced flashover occurred in the roof void and flames extending from this compartment entered the living spaces below. It is important to emphasize that flashover is a rapid transition to the fully developed stage of fire development.

Indicators of significant fire behavior

- 911 Dispatch received multiple phone calls reporting a residential structure fire

- First arriving crews could smell smoke and see smoke before arriving on-scene

- First arriving crews encountered limited visibility in the street as they approached the scene

- E-26 Captain reported heavy smoke coming from a one-story wood-frame residence

- Large residential structure with approximately 4,200 ft2 of living space (full 360-degree size-up not completed due to limited access to Side-C)

- Sustained wind from the east / south-east hitting Side-C

- L-26 Captain observed fire above roofline coming from rear C-D area (likely from roof vent(s)) near area of origin

- L-26 Captain observed fire overlapping eave at Side-C as crew ventilated roof

- E-26, E-36, and L-29 crews reported heavy smoke banked down from ceiling to near floor level at the front door

- Increasing heat in front hallway. E-26 crew reportedly entered standing up. E-36 and L-29 crew followed and reported high heat. L-29 forced to crawl in due to high heat

- E-36 captain attempted to use TIC but optically-dense thick smoke obscured the screen

- Flames emerged through roof cut just behind saw as roof was being ventilated

- Large flames erupted through vent hole when L-26 captain punched through ceiling with pike pole

- Fuel-rich smoke in the front hallway / living room / den areas erupted into flames moments after the roof was vented and ceiling was punched

- After venting roof, the flames overlapping eave grew from a few feet wide to over 20 feet wide and raced up the roof

- Interior crews reported hearing a loud roar or whooshing sound as flames engulfed them

- Interior crews felt a rapid and significant increase in heat

- Interior crews reported an orange glow from ceiling down to almost floor level in living room, hallway and den areas

- Water from two 1 ¾-inch hose lines inside structure was insufficient to control fire growth

- Deteriorating conditions prompted command officers to order evacuation and change to defensive operations

- Interior crew members exited with helmets on fire

- Large volume of fire exited front doorway and windows, overlapping Side-A eave.

Note: The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is developing a computerized fire model to aid in reconstructing the events of the fire. When completed, this model will be available at the NIST website: http://www.nist.gov/fire/. (Link Updated 8/8/2013)

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatality:

- An inadequate size-up prior to committing to tactical operations

- Lack of understanding of fire behavior and fire dynamics

- Fire in a void space burning in a ventilation controlled regime

- High winds

- Uncoordinated tactical operations, in particular fire control and tactical ventilation

- Failure to protect the means of egress with a backup hose line

- Inadequate fireground communications

- Failure to react appropriately to deteriorating conditions.

CAUSE OF DEATH

According to the County Coroners report, the cause of death for Victim # 1 was listed as thermal injuries. The cause of death for Victim # 2 was listed as thermal injuries and smoke inhalation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation # 1: Fire departments should ensure that an adequate initial size-up and risk assessment of the incident scene is conducted before beginning interior fire fighting operations.

Discussion: Among the most important duties of the first officer on the scene is conducting an initial size-up of the incident. This information lays the foundation for the entire operation. It determines the number of fire fighters and the amount of apparatus and equipment needed to control the blaze, assists in determining the most effective point of fire extinguishment attack, the most effective method of venting heat and smoke, and whether the attack should be offensive or defensive. A proper size-up begins from the moment the alarm is received and it continues until the fire is under control. The size-up should also include assessments of risk versus gain during incident operations. 8, 13-19 Retired Chief Alan Brunacini recommends that the arriving IC drive partially or completely around the structure whenever possible to get a complete view of the structure. While this may delay the ICs arrival by a few seconds, this drive-by may provide significant details not visible from the command post.15 The size-up should include an evaluation of factors such as the fire size and location, length of time the fire has been burning, conditions on arrival, occupancy, fuel load and presence of combustible or hazardous materials, exposures, time of day, and weather conditions. Information on the structure itself including size, construction type, age, condition (evidence of deterioration, weathering, etc), evidence of renovations, lightweight construction, loads on roof and walls (air conditioning units, ventilation ductwork, utility entrances, etc.), and available pre-plan information are all key information which can effect whether an offensive or defensive strategy is employed. The size-up and risk assessment should continue throughout the incident.

Interior size-up is just as important as exterior size-up. Since the IC is staged at the command post (outside), the interior conditions should be communicated to the IC as soon as possible. Interior conditions could change the ICs strategy or tactics. For example, if heavy smoke is emitting from the exterior roof system, but fire fighters cannot find any fire in the interior, it is a good possibility that the fire is above them in the roof system. Other warning signs that should be relayed to the IC include dense black smoke, turbulent smoke, smoke puffing around doorframes, discolored glass, and a reverse flow of smoke back inside the building. It is important for the IC to immediately obtain this type of information to help make the proper decisions. Departments should ensure that the first officer or fire fighter inside the structure evaluates interior conditions and reports them immediately to the IC.

In this incident, the first arriving companies officers concentrated on fast attack procedures at the front entrance (A-side) and on the roof. First arriving companies could have observed three sides of the structure (B-side, A-side and D-side), but visibility was limited due to the amount of optically-dense smoke blowing across the street. The incident commander established the command post behind the first three apparatus that arrived on-scene. A complete 360 degree size-up was not attempted until after the roof ventilation crew descended from the roof after completing roof ventilation at approximately 0020 hours, but the 360 degree size-up was not completed due to the brick wall and fence at the D-side. Another 360 degree walk-around was attempted when an arriving district chief was assigned as Sector C command at approximately 0035 hours. Sector C Command and the E-29 crew moved to the D-side, but again, the size-up was not completed due to the brick wall and fence. A full 360 degree size-up conducted early during the incident may have identified fire conditions at the C-side, the condition of the atrium windows or other factors that could have influenced a change in the operational tactics used during the event.

Recommendation # 2: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters and officers have a sound understanding of fire behavior and the ability to recognize indicators of fire development and the potential for extreme fire behavior (such as smoke color, velocity, density, visible fire, heat).

Discussion: Reading fire behavior indicators and recognizing fire conditions serve as the basis for predicting likely and potential fire behavior. Reading the fire requires recognition of patterns of key fire behavior indicators. It is essential to consider these indicators together and not to focus on the most obvious indicators or one specific indicator (e.g., smoke). 12, 20 Identifying building factors, smoke, wind direction, air movement, heat and flame indicators are all critical to reading the fire. Focusing on reading smoke may result in fire fighters missing other critical indicators of potential fire behavior. One important concept that must be emphasized is that smoke is fuel and must be viewed as potential energy.

Since the IC is staged at the command post (outside), the interior conditions should be communicated by interior company officers (or the member supervising the crew) as soon as possible to their supervisor (the IC, division supervisor, etc.). Interior conditions could change the ICs strategy or tactics. Interior crews can aid the IC in this process by providing reports of the interior conditions as soon as they enter the fire building and by providing regular updates. In addition to the importance of communicating reports on fire conditions, it is essential that fire fighters recognize what information is important. Command effectiveness can be impaired by excessive and extraneous information as well as from a lack of information. In the case of communicating observations related to fire behavior, this requires development of fire fighters skill in recognition of key fire behavior indicators and reading the fire.

In this incident, the first arriving companies found the street obscured by optically-dense thick smoke, which made identifying the involved residence difficult. Crews reported encountering a smoke-filled hallway with smoke banked down to near floor level when they entered the front door. Interior conditions rapidly deteriorated soon after the crews entered and the roof was ventilated. Thick fuel-rich smoke ignited, engulfed the interior crews, and possibly caused the two victims to become disoriented. The E-26 and E-36 attack lines were ineffective at controlling the fire or protecting the fire fighters. No interior size-up reports were communicated to the IC. The IC requested size-up reports via radio on several occasions.

Recommendation # 3: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained to recognize the potential impact of windy conditions on fire behavior and implement appropriate tactics to mitigate the potential hazards of wind-driven fire.

Discussion: Fire departments should develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) for incidents with high-wind conditions including defensive attack if necessary. It is important that fire fighters develop an understanding of how wind conditions influence fire behavior and tactics that may be effective under wind-driven conditions. Wind conditions can have a major influence on structural fire behavior. When wind speeds exceed 10 mph (16 km/hr) all fire fighters (incident commanders, company officers, crew members) should use caution and take wind direction and speed into account when selecting strategies and tactics. NIST research has determined that wind speeds as low as 10 mph (16 km/hr) are sufficient to create wind-driven fire conditions if the flow path is uncontrolled.21 NIST, in a recent study on wind-driven fires in structures, has shown that wind speeds as low as 10 mph can turn a routine room and contents fire into a floor to ceiling fire storm or blowtorch effect, generating untenable conditions for fire fighters, even outside of the room of origin. Temperatures in excess of 600 ºC (1100 ºF) and total heat fluxes in excess of 70 kW/m⊃2; were measured at 4 ft above the floor along the flow path between the fire room and the downwind exit vent. These conditions were attained within 30 seconds of the flow path being formed by an open vent on the upwind side of the structure and an open vent on the downwind side of the structure. 21

Incident commanders and company officers should change their strategy when encountering high wind conditions. An SOP should be developed to include obtaining the wind speed and direction, and guidelines established for possible scenarios associated with the wind speed and the possible fuel available, similar to that in wildland fire fighting.22 Under wind-driven conditions an exterior attack from the upwind side of the fire may be necessary to reduce fire intensity to the extent that fire fighters can gain access to the involved compartments. If the fire is on an upper floor, this method may require the use of an aerial or portable ladder. In addition to exterior attack from upwind, use of a wind control device to cover ventilation inlet openings on the upwind side may also aid in reducing wind-driven fire conditions (see Photo 7).11

|

|

Photo 7. Two different types of Wind Control Devices being used to decrease the wind fed to the fire. |

Fire departments must ensure that fire fighters are adequately trained and competent to implement SOPs that cover operating in windy conditions. In this incident, fire fighters encountered sustained winds measured at 17 mph with wind gusts to 26 mph blowing from the Side C (rear) of the structure toward the Side A (front). These winds probably served to accelerate the fire growth and spread within the structure. Wind-driven fire conditions were not detected by the first arriving crews and a full 360-degree size-up (which may have detected fire conditions at Side C) was not completed since access to both sides and the rear of the structure were limited by fences and the structures location at the top of a steep embankment.

Recommendation # 4: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters understand the influence of ventilation on fire behavior and effectively apply ventilation and fire control tactics in a coordinated manner.

Discussion: Ventilation is often defined as the systematic removal of heated air, smoke, and fire gases from a burning building and replacing them with fresh air.8 Considering that most fires beyond the incipient stage are or will quickly become ventilation controlled, changes in ventilation are likely to be some of the most significant factors in changing fire behavior. In some cases, these changes are caused by the fire acting on building materials (fire self-venting through roofs or exterior walls, windows failing, etc.), while in other cases fire behavior is influenced (positively or negatively) by tactical operations.8 Fire fighters must recognize that opening a door to make entry for fire attack or search and rescue operations can have as much influence on ventilation as opening a window to purposefully vent smoke and products of combustion.8

Properly coordinated ventilation can decrease how fast the fire spreads, increase visibility, and lower the potential for flashover or backdraft. Proper ventilation reduces the threat of flashover by removing heat before combustibles in a room or enclosed area reach their ignition temperatures, and can reduce the risk of a backdraft by reducing the potential for superheated fire gases and smoke to accumulate in an enclosed area. Properly ventilating a structure fire will reduce the tendency for rising heat, smoke, and fire gases, trapped by the roof or ceiling, to accumulate, bank down, and spread laterally to other areas within the structure. The ventilation opening may produce a chimney effect causing air movement from within a structure toward the opening. This air movement helps facilitate the venting of smoke, hot gases and products of combustion, but may also cause the fire to grow in intensity and may endanger fire fighters who are between the fire and the ventilation opening. For this reason, ventilation should be closely coordinated with hoseline placement and offensive fire suppression tactics. Close coordination means the hoseline is in place and ready to operate so that when ventilation occurs, the hoseline can overcome the increase in combustion likely to occur. If a ventilation opening is made directly above a fire, fire spread may be reduced, allowing fire fighters the opportunity to extinguish the fire. If the opening is made elsewhere, the chimney effect may actually contribute to the spread of the fire.23

Fire development in a compartment may be described in several stages, although the boundaries between these stages may not be clearly defined.8 The incipient stage starts with ignition, followed by growth, fully developed, and decay stages. The available fuel largely controls the growth of the fire during the early stages. This is known as a fuel controlled fire and ventilation during this time may initially slow the spread of the fire as smoke, hot gases and products of incomplete combustion are removed. As noted above, increased ventilation can also cause the fire to grow in intensity as additional oxygen is introduced. Effective application of water during this time can suppress the fire but if the fire is not quickly knocked down, it may continue to grow.

If the fire grows until the compartment approaches a fully developed state, the fire is likely to become ventilation controlled. Further fire growth is limited by the available air supply as the fire consumes the oxygen in the compartment. Ventilating the compartment at this point will allow a fresh air supply (with oxygen to support combustion) which may accelerate the fire growth resulting in an increased heat release rate. A ventilation induced flashover can occur when ventilation provides an increased air supply if coordinated fire suppression activities do not quickly decrease the heat release rate.8

In this incident, vertical ventilation was initiated just to the left of the front door where interior crews were advancing into the structure. The L-26 captain discussed the fire conditions with the IC but the interior conditions were not communicated to the IC or the roof ventilation crew. Fire erupted from the ventilation hole on the roof as soon as the opening was made, exposing the fire burning in the concealed attic space. The L-26 crew punched through the ceiling from the roof while the E-36 crew pulled ceiling inside the house, adding to the ventilation openings. These actions increased air supply to the ventilation controlled fire burning in the void space between the ceiling and roof. Flames in the attic ignited the fuel-rich smoke on the ground floor. Rapid fire development on the ground floor may have resulted in failure of windows on Side C providing a flow path for wind driven fire from Side C through the door on Side A.

Recommendation # 5: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters and officers understand the capabilities and limitations of thermal imaging cameras (TIC) and that a TIC is used as part of the size-up process

Discussion: Thermal imaging cameras (TICs) can be a useful tool for initial size up and for locating the seat of a fire. Infrared thermal cameras can assist fire fighters in quickly getting crucial information about the location of the source (seat) of the fire from the exterior of the structure which can help the IC plan an effective and rapid response. Knowing the location of the most dangerous and hottest part of the fire may help fire fighters determine a safer approach and avoid exposure to structural damage in a building that might have otherwise been undetectable. A fire fighter about to enter a room filled with flames and smoke can use a TIC to assist in judging whether or not it will be safe from falling beams, walls, or other dangers. While TICs provide useful information to aid in locating the seat of a fire, they cannot be relied upon to assess the strength or safety of floors and ceilings.27 TICs should be used in a timely manner, and fire fighters should be properly trained in their use and be aware of their limitations.24-25 While use of a TIC is important, research by Underwriters Laboratories has shown that there are significant limitations in the ability of these devices to detect temperature differences behind structural materials such as the exterior finish of a building or outside compartment linings (walls, ceilings, and floors).26 Fire fighters and officers should be wary of relying on this technology alone, and must integrate this data with other fire behavior indicators to determine potential fire conditions. TICs may not provide adequate size-up information in all cases, but using one is preferred to not using one.

In this incident, the use of a TIC prior to entry into the structure may have given an indication that fire was actively burning in the attic space. This information could have served as an indicator that more defensive tactics should be considered, such as not advancing down the hallway until the fire overhead was controlled. TICs were available on the fireground and at least one was used in the hallway during the initial attack but the screen could not be seen due to the thick black smoke in the hallway. A TIC was also used during the initial rescue attempt but the screen turned white due to the intense heat.

Recommendation # 6: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained to check for fire in overhead voids upon entry and as charged hoselines are advanced.

Discussion: Fire fighters may have difficulty in finding the exact location of fire in a building, even though heavy smoke makes it clear that fire is present. Fire or heavy smoke from the roof suggests that the fire could be in concealed areas of the roof system. When fire is suspected to be burning above a ceiling, fire fighters should use a pike pole or other tools to open up the ceiling immediately and check for smoke and signs of fire. The safest location for fire fighters is to make this examination while standing near a doorway in case rapid escape is necessary. When opening ceilings or other concealed spaces, it is important to have a charged hoseline ready. If a smoke layer is present, cooling the gases using short pulses of water fog before opening the ceiling reduces the potential that the smoke may be ignited by flames in the void space. 8, 12

If there is a fire barrier in the void, the same procedure should take place on the opposite side of the barrier. If the fire emerges behind the fire fighter, egress may be cut off, leading to the possibility of entrapment. Fire fighters need to be aware of their location in relation to the nearest exit and also be aware of the location of other fire fighters in the area. Fire fighters also need to ensure they have proper hose pressure before entering the fire area, bleeding the nozzle at the front door to ensure adequate water flow is available. The IC must consider and provide for alternative egress routes from all locations where fire fighters are operating. 27-28

In this incident, crews advanced down the front hallway and into the adjacent living room while fire burned undetected overhead. At the same time, the roof was being vented and crews may have advanced beyond the point where the roof was opened and the ceiling punched through. A crew also reported pulling ceiling well inside the front door. These separate and uncoordinated actions may have resulted in the rapid fire growth seen in this incident when the fuel-rich smoke ignited.

Recommendation # 7: Fire departments should develop, implement and enforce a detailed Mayday Doctrine to ensure that fire fighters can effectively declare a Mayday.

Discussion: Dr. Burton Clark, EFO, CFO, and noted Mayday Doctrine advocate with the U.S. Fire Administration, National Fire Academy has studied the need for enhanced Mayday training across the country. According to Dr. Clark, There are no national Mayday Doctrine standards to which fire fighters are required to be trained. 29 The NFPA 1001 fire fighter I & II standards 30 and the Texas Fire Fighter certification do not include any Mayday Doctrine performance, knowledge or skills. The word Mayday is not defined or referenced in either standard. In addition there are no national or state standards related to required continuing recertification of fire fighters to insure their continued Mayday competency throughout their career. In several investigations conducted by NIOSH, including a previous investigation at this department, NIOSH recommended that fire departments train fire fighters on initiating emergency traffic.2, 31-34

Both victims received Mayday training from the department, but the training does not appear to have been adequate. Victim # 1, a recent recruit, received department-provided Mayday training during the 3rd, 10th, and 17th weeks of his recruit class. All members of the recruit class passed Mayday evolutions. Following the incident, Victim # 1s radio was found to be turned off and set on the dispatch channel. There is no evidence on the fireground audio recordings of a Mayday transmission. Victim # 2 had also received training that encompassed initiating a Mayday, but he could not have called a Mayday since he did not have his radio with him.

The National Fire Academy has two courses addressing fire fighter Mayday Doctrine: Q133 Firefighter Safety: Calling the Mayday which is a 2 hour program covering the cognitive and affective learning domain of firefighter Mayday Doctrine and H134 Calling the Mayday: Hands on Training which is an 8 hour course that covers the psychomotor learning domain of firefighter Mayday Doctrine. These materials are based on the military methodology use to develop and teach fighter pilots ejection doctrine. A training CD is available to fire departments free of charge from the US Fire Administration Publications office. 35, 36

Recommendation # 8: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained in fireground survival procedures.

Discussion: As part of emergency procedures training, fire fighters need to understand that their personal protective equipment (PPE) and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) do not provide unlimited protection. Fire fighters should be trained to stay low when advancing into a fire as extreme temperature differences may occur between the ceiling and floor. When confronted with rapidly worsening fire conditions, the action to take depends on whether the crew has a hoseline or not. If not, the first action must be immediate egress from the building or to a place of safe refuge (e.g., behind a closed door in an uninvolved compartment). If they have a hoseline, a tactical withdrawal while continuing water application would be the first action that should be taken. Conditions are likely to become untenable in a matter of seconds. In such cases, delay in egress to transmit a Mayday message may be fatal. However, the Mayday message should be transmitted as soon as the crew is in a defensible position.