Youth and Tobacco Use

Youth use of tobacco in any form is unsafe.

If smoking continues at the current rate among youth in this country, 5.6 million of today’s Americans younger than 18 will die early from a smoking-related illness. That’s about 1 of every 13 Americans aged 17 years or younger alive today.1

Background

Preventing tobacco use among youth is critical to ending the tobacco epidemic in the United States.

- Tobacco use is started and established primarily during adolescence.2,3

- Nearly 9 out of 10 cigarette smokers first tried smoking by age 18, and 99% first tried smoking by age 26.1,3

- Each day in the United States, more than 3,200 youth aged 18 years or younger smoke their first cigarette, and an additional 2,100 youth and young adults become daily cigarette smokers.1

- Flavorings in tobacco products can make them more appealing to youth.4

- In 2014, 73% of high school students and 56% of middle school students who used tobacco products in the past 30 days reported using a flavored tobacco product during that time.

Estimates of Current Tobacco Use Among Youth

Cigarettes

- From 2011 to 2016, current cigarette smoking declined among middle and high school students.5,6

- About 2 of every 100 middle school students (2.2%) reported in 2016 that they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days—a decrease from 4.3% in 2011.

- 8 of every 100 high school students (8.0%) reported in 2016 that they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days—a decrease from 15.8% in 2011.

Electronic cigarettes

- Current use of electronic cigarettes increased among middle and high school students from 2011 to 2016.5,6

- About 4 of every 100 middle school students (4.3%) reported in 2016 that they used electronic cigarettes in the past 30 days—an increase from 0.6% in 2011.

- About 11 of every 100 high school students (11.3%) reported in 2016 that they used electronic cigarettes in the past 30 days—an increase from 1.5% in 2011.

Hookahs

- From 2011 to 2016, current use of hookahs increased among middle and high school students.5,6

- 2 of every 100 middle school students (2.0%) reported in 2016 that they had used hookah in the past 30 days—an increase from 1.0% in 2011.

- Nearly 5 of every 100 high school students (4.8%) reported in 2016 that they had used hookah in the past 30 days—an increase from 4.1% in 2011.

Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011-2016

Larger infographic

Smokeless Tobacco

- In 20165:

- About 2 of every 100 middle school students (2.2%) reported current use of smokeless tobacco.

- Nearly 6 of every 100 high school students (5.8%) reported current use of smokeless tobacco.

All Tobacco Product Use

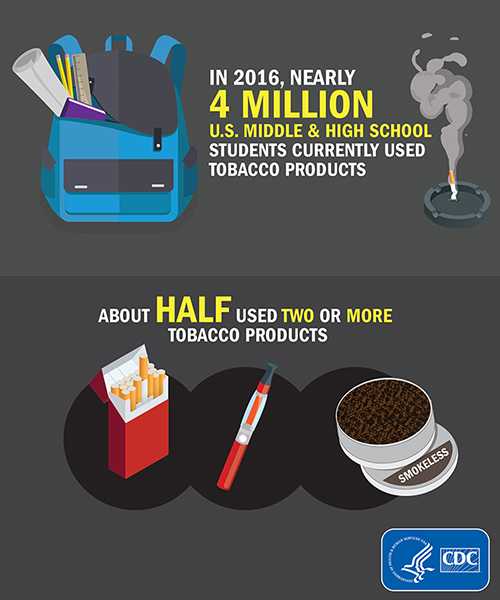

- In 2016, about 7 of every 100 middle school students (7.2%) and about 20 of every 100 high school students (20.2%) used some type of tobacco product.5

- In 2013, nearly 18 of every 100 middle school students (17.7%) and nearly half (46.0%) of high school students said they had ever tried a tobacco product.7

Use of multiple tobacco products is prevalent among youth.3

- In 2016, about 3 of every 100 middle school students (3.1%) and nearly 10 of every 100 high school students (9.6%) reported use of two or more tobacco products in the past 30 days.5

- In 2013, more than 31 of every 100 high school students (31.4%) said they had ever tried two or more tobacco products.7

Youth who use multiple tobacco products are at higher risk for developing nicotine dependence and might be more likely to continue using tobacco into adulthood.7

Notes:

“Current use” is determined by respondents indicating that they have used a tobacco product on at least 1 day during the past 30 days.

| Tobacco Product | Overall | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any tobacco product† | 20.2% | 17.0% | 23.5% |

| Electronic cigarettes | 11.3% | 9.5% | 13.1% |

| Cigarettes | 8.0% | 6.9% | 9.1% |

| Cigars | 7.7% | 5.6% | 9.0% |

| Smokeless tobacco | 5.8% | 3.3% | 8.3% |

| Hookahs | 4.8% | 5.1% | 4.5% |

| Pipe tobacco | 1.4% | 0.9% | 1.8% |

| Bidis | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| Tobacco Product | Overall | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|

| *Use is determined by respondents indicating that they have used a tobacco product on at least 1 day during the past 30 days.

†Any tobacco product includes cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco (including chewing tobacco, snuff, dip, snus, and dissolvable tobacco), tobacco pipes, bidis, hookah, and electronic cigarettes. §Where percentages are missing, sample sizes were less than 50 and thus considered unreliable. |

|||

| Any tobacco product† | 7.2% | 5.9% | 8.3% |

| Electronic cigarettes | 4.3% | 3.4% | 5.1% |

| Cigarettes | 2.2% | 1.8% | 2.5% |

| Smokeless tobacco | 2.2% | 1.5% | 3.0% |

| Cigars | 2.2% | 1.7% | 2.7% |

| Hookahs | 2.0% | 1.9% | 2.1% |

| Pipe tobacco | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.8% |

| Bidis | 0.3% | –§ | 0.4% |

Factors Associated With Youth Tobacco Use

Factors associated with youth tobacco use include the following:

- Social and physical environments2,8

- The way mass media show tobacco use as a normal activity can promote smoking among young people.

- Youth are more likely to use tobacco if they see that tobacco use is acceptable or normal among their peers.

- High school athletes are more likely to use smokeless tobacco than their peers who are non-athletes.9

- Parental smoking may promote smoking among young people.

- Biological and genetic factors2

- There is evidence that youth may be sensitive to nicotine and that teens can feel dependent on nicotine sooner than adults.

- Genetic factors may make quitting smoking more difficult for young people.

- A mother’s smoking during pregnancy may increase the likelihood that her offspring will become regular smokers.

- Mental health: There is a strong relationship between youth smoking and depression, anxiety, and stress.2

- Personal perceptions: Expectations of positive outcomes from smoking, such as coping with stress and controlling weight, are related to youth tobacco use.2

- Other influences that affect youth tobacco use include:2,8

- Lower socioeconomic status, including lower income or education

- Lack of skills to resist influences to tobacco use

- Lack of support or involvement from parents

- Accessibility, availability, and price of tobacco products

- Low levels of academic achievement

- Low self-image or self-esteem

- Exposure to tobacco advertising

Reducing Youth Tobacco Use

National, state, and local program activities have been shown to reduce and prevent youth tobacco use when implemented together. They include the following:

- Higher costs for tobacco products (for example, through increased taxes)2,10,11

- Prohibiting smoking in indoor areas of worksites and public places2,10,11

- Raising the minimum age of sale for tobacco products to 21 years, which has recently emerged as a potential strategy for reducing youth tobacco use11

- TV and radio commercials, posters, and other media messages targeted toward youth to counter tobacco product advertisements2,10

- Community programs and school and college policies and interventions that encourage tobacco-free environments and lifestyles2,10

- Community programs that reduce tobacco advertising, promotions, and availability of tobacco products2,10

Some social and environmental factors have been found to be related to lower smoking levels among youth. Among these are:2

- Religious participation

- Racial/ethnic pride and strong racial identity

- Higher academic achievement and aspirations

Continued efforts are needed to prevent and reduce the use of all forms of tobacco use among youth.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1994 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flavored Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2015;64(38):1066–70 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2017;66(23):597-603 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011 and 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2013;62(45):893–7 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2014;63(45):1021–6 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2000 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Combustible and Smokeless Tobacco Use Among High School Athletes—United States, 2001–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2015;64(34):935–9 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2014. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- King BA, Jama AO, Marynak KL, Promoff GR. Attitudes Toward Raising the Minimum Age of Sale for Tobacco Among U.S. Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2015-49(4):583-8. [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

For Further Information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Office on Smoking and Health

E-mail: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Phone: 1-800-CDC-INFO

Media Inquiries: Contact CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health press line at 770-488-5493.

- Page last reviewed: September 20, 2017

- Page last updated: September 20, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir