We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

Pulmonary edema

From WikEM

(Redirected from Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema)

Contents

Background

Pulmonary Edema Types

Cardiogenic pulmonary edema

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Negative pressure pulmonary edema

- Upper airway obstruction

- Reexpansion edema

- Neurogenic causes

- Iatrogenic fluid overload

- Multiple blood transfusions

- IV fluid

- Inhalation injury

- Pulmonary contusion

- Aspiration pneumonia and pneumonitis

- Other

Clinical Features

- Crackles

- Respiratory distress

- Increased jugular venous distension

- Signs of poor organ perfusion

Differential Diagnosis

Shortness of breath

Emergent

- Pulmonary

- Airway obstruction

- Anaphylaxis

- Aspiration

- Asthma

- Cor pulmonale

- Inhalation exposure

- Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Pneumonia

- Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP)

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Tension pneumothorax

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis acute exacerbation

- Cardiac

- Other Associated with Normal/↑ Respiratory Effort

- Other Associated with ↓ Respiratory Effort

Non-Emergent

- ALS

- Ascites

- Uncorrected ASD

- Congenital heart disease

- COPD exacerbation

- Fever

- Hyperventilation

- Neoplasm

- Obesity

- Panic attack

- Pleural effusion

- Polymyositis

- Porphyria

- Pregnancy

- Rib fracture

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

- Thyroid Disease

Evaluation

- CBC (rule out anemia)

- Chem

- ECG

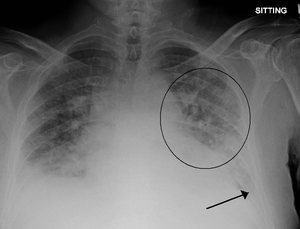

- CXR

- Cephalization

- Interstitial edema

- Pulmonary venous congestion

- Pleural effusion

- Alveolar edema

- Cardiomegaly

- Troponin?

- Ultrasound

- Bedside to assess global function, B lines, assessment of IVC

- Formal TTE/TEE

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)[1]

- Biologically active metabolite of proBNP (released from ventricles in response to increased volume/pressure)

- Utility is controversial and may not affect patient centered outcomes[2]

- May be trended to gauge treatment response in acute decompensated CHF

- May have false negative with isolated diastolic dysfunction

- Measurement

- <100 pg/mL: Negative for acute CHF (Sn 90%, NPV 89%)

- 100-500 pg/mL: Indeterminate (Consider differential diagnosis and pre-test probability)

- >500 pg/mL: Positive for acute CHF (Sp 87%, PPV 90%)

NT-proBNP[3][4][5]

- N-terminal proBNP (biologically inert metabolite of proBNP)

- <300 pg/mL → CHF unlikely

- CHF likely in:

- >450 pg/mL in age < 50 years old

- >900 pg/mL in 50-75 years old

- >1800 pg/mL in > 75 years old

Differential Diagnosis (Elevated BNP)

BNP In Obese Patients

- Visceral fat expansion leads to increased clearance of active natriuretic peptides[6]

- Obese patients also frequently treated for hypertension or coronary artery disease which may also contribute to lower BNP levels

Interpretation

- In one study of 204 patients with acute CHF, an inverse relationship between BMI and BNP was noted. The standard cutoff of 100pg/mL resulted in a 20% false-negative rate[7]

- Analysis of a subgroup of patients with documented BMI from the Breathing Not Properly study showed that a lower cutoff was more appropriate to maintain 90% sensitivity in obese and morbidly obese patients (54pg/mL)[8]

Management

- CPAP/BiPAP with PEEP 6-8; titrate up to PEEP of 10-12

- Nitroglycerin

- Dosing Options

- Sublingual 0.4mg q5min

- Nitropaste (better bioavailability than oral Nitroglycerin)

- Intravenous: 0.1mcg/kg/min - 5mcg/kg/min

- Generally start IV Nitroglycerin 50mcg/min and titrate rapidly (150mcg/min or higher) to symptom relief

- Nursing may be resistant. Explain that 1 SL tab (400 mcg) Q4min = 100 mcg/min for perspective.

- Dosing Options

- If NTG fails to reduce BP consider nitroprusside (reduces both preload and afterload) or ACE-inhibitiors (preload reducer)

- After patient improves titrate down NTG as enaliprilat (0.625 - 1.25mg IV) or captopril are started

- Morphine is no longer recommended do to increased morbidity[9][10]

Disposition

See Also

- Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- Sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema (SCAPE)

References

- ↑ Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):161-167. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020233.

- ↑ Carpenter CR et al. BRAIN NATRIURETIC PEPTIDE IN THE EVALUATION OF EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT DYSPNEA: IS THERE A ROLE? J Emerg Med. 2012 Feb; 42(2): 197–205.

- ↑ Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, et al. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study. Eur Heart J. 2006 Feb. 27(3):330-7.

- ↑ Kragelund C, Gronning B, Kober L, Hildebrandt P, Steffensen R. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term mortality in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2005 Feb 17. 352(7):666-75.

- ↑ Moe GW, Howlett J, Januzzi JL, Zowall H,. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide testing improves the management of patients with suspected acute heart failure: primary results of the Canadian prospective randomized multicenter IMPROVE-CHF study. Circulation. 2007 Jun 19. 115(24):3103-10.

- ↑ Clerico A, Giannoni A, Vittorini S, Emdin M. The paradox of low BNP levels in obesity. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;17(1):81-96. doi:10.1007/s10741-011-9249-z.

- ↑ Krauser DG, Lloyd-Jones DM, Chae CU, et al. Effect of body mass index on natriuretic peptide levels in patients with acute congestive heart failure: A ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) substudy. Am Heart J. 2005;149(4):744-750. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.010.

- ↑ Daniels LB, Clopton P, Bhalla V, et al. How obesity affects the cut-points for B-type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of acute heart failure. Results from the Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study. Am Heart J. 2006;151(5):999-1005. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.10.011.

- ↑ Peacock WF, Hollander JE, Diercks DB, Lopatin M, Fonarow G, Emerman CL. Morphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE analysis. Emerg Med J. 2008 Apr;25(4):205-9.

- ↑ Ellingsrud C, Agewall S. Morphine in the treatment of acute pulmonary oedema--Why? Int J Cardiol. 2016 Jan 1;202:870-3.