Better water system maintenance needed to prevent Legionnaires' disease outbreaks

New toolkit offers practical tips for reducing germ’s growth, spread in building water systems

This website is archived for historical purposes and is no longer being maintained or updated.

Press Release

Embargoed Until: Tuedsay, June 7, 2016, 11:30 a.m. ET

Contact:

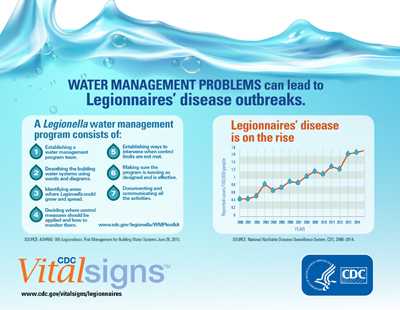

Water Management problems can lead to Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks.

Entire infographic

More effective water management might have prevented most of the Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks CDC investigated from 2000 through 2014, according to today’s CDC Vital Signs report.

Problems identified in these building-associated outbreaks included inadequate disinfectant levels, human error, and equipment breakdowns that led to growth of Legionella bacteria in water systems. CDC is releasing a new toolkit today to help building owner and managers prevent these problems.

Legionnaires’ disease is on the rise. In the last year, about 5,000 people were diagnosed with Legionnaires’ disease and more than 20 outbreaks were reported to CDC. Legionnaires’ disease is a serious type of lung infection (pneumonia) that people can get by breathing in small droplets of water contaminated with Legionella. Most people who get sick need hospital care and make a full recovery— but about 1 in 10 people will die from the infection.

“Many of the Legionnaire’s disease outbreaks in the United States over the past 15 years could have been prevented,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, M.D. M.P.H. “Better water system management is the best way to reduce illness and save lives, and today’s report promotes tools to make that happen.”

The Vital Signs report examined 27 building-associated Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks investigated by CDC across 24 states and territories, Mexico, and Canada. For each outbreak, CDC researchers recorded the location, source of exposure, and deficiencies in environmental control of Legionella.

The most common source of building-associated Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks was drinkable water (56 percent), such as water used for showering, followed by cooling towers (22 percent), and hot tubs (7 percent). Other sources included industrial equipment (4 percent) and a decorative fountain/water feature (4 percent). In two outbreaks, the source was never identified.

Twenty-three of the investigations included descriptions of failures that contributed to the outbreak. In nearly half, more than one type of failure was identified.

- About 2 in 3 (65 percent) were due to process failures, like not having a Legionella water management program.

- About 1 in 2 (52 percent) were due to human error, such as a hot tub filter not being cleaned or replaced as recommended by the manufacturer.

- About 1 in 3 (35 percent) were due to equipment, such as a disinfection system, not working.

- About 1 in 3 (35 percent) were due to changes in water quality from reasons external to the building itself, like nearby construction.

New toolkit for Legionnaires’ disease prevention

CDC today released a new toolkit for building owners and managers: em>Developing a Water Management Program to Reduce Legionella Growth & Spread in Buildings: A Practical Guide to Implementing Industry Standards. Based on ASHRAE Standard 188, a document for building engineers, the toolkit provides a checklist to help identify if a water management program is needed, examples to help identify where Legionella could grow and spread in a building, and ways to reduce the risk of Legionella contamination.

“Years of outbreak response have taught us where to find Legionella hot spots,” said Nancy Messonnier, M.D., director of CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. “The toolkit will help building owners and managers better understand where those hot spots are and put measures in place to reduce the risk of Legionnaires’ disease.”

Most healthy people do not get Legionnaires’ disease after being exposed to Legionella. People at increased risk of Legionnaire’s disease are 50 years of age or older and have certain risk factors, such as being a current or former smoker, having a chronic lung disease, or having a weakened immune system.

For more information on today’s Vital Signs, visit www.cdc.gov/VitalSigns. For more information on Legionella, Legionnaires’ disease, and the CDC toolkit visit www.cdc.gov/legionella.

- Page last reviewed: June 7, 2016 (archived document)

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir