Poliomyelitis

On this Page

Poliomyelitis

- First described by Michael Underwood in 1789

- First outbreak described in U.S. in 1843

- More than 21,000 paralytic cases reported in the U.S. in 1952

- Global eradication within next decade

The words polio (grey) and myelon (marrow, indicating the spinal cord) are derived from the Greek. It is the effect of poliomyelitis virus on the spinal cord that leads to the classic manifestation of paralysis.

Records from antiquity mention crippling diseases compatible with poliomyelitis. Michael Underwood first described a debility of the lower extremities in children that was recognizable as poliomyelitis in England in 1789. The first outbreaks in Europe were reported in the early 19th century, and outbreaks were first reported in the United States in 1843. For the next hundred years, epidemics of polio were reported from developed countries in the Northern Hemisphere each summer and fall. These epidemics became increasingly severe, and the average age of persons affected rose. The increasingly older age of persons with primary infection increased both the disease severity and number of deaths from polio. Polio reached a peak in the United States in 1952, with more than 21,000 paralytic cases. However, following introduction of effective vaccines, polio incidence declined rapidly. The last case of wild-virus polio acquired in the United States was in 1979, and global polio eradication may be achieved within this decade.

Poliovirus

Poliovirus

- Enterovirus (RNA)

- Three serotypes: 1, 2, 3

- Minimal heterotypic immunity between serotypes

- Rapidly inactivated by heat, formaldehyde, chlorine, ultraviolet light

Poliovirus is a member of the enterovirus subgroup, family Picornaviridae. Enteroviruses are transient inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract, and are stable at acid pH. Picornaviruses are small, ether-insensitive viruses with an RNA genome.

There are three poliovirus serotypes (P1, P2, and P3). There is minimal heterotypic immunity between the three serotypes. That is, immunity to one serotype does not produce significant immunity to the other serotypes.

The poliovirus is rapidly inactivated by heat, formaldehyde, chlorine, and ultraviolet light.

Pathogenesis

Poliomyelitis Pathogenesis

- Entry into mouth

- Replication in pharynx, GI tract

- Hematologic spread to lymphatics and central nervous system

- Viral spread along nerve fibers

- Destruction of motor neurons

The virus enters through the mouth, and primary multiplication of the virus occurs at the site of implantation in the pharynx and gastrointestinal tract. The virus is usually present in the throat and in the stool before the onset of illness. One week after onset there is less virus in the throat, but virus continues to be excreted in the stool for several weeks. The virus invades local lymphoid tissue, enters the bloodstream, and then may infect cells of the central nervous system. Replication of poliovirus in motor neurons of the anterior horn and brain stem results in cell destruction and causes the typical manifestations of poliomyelitis.

Clinical Features

The incubation period for nonparalytic poliomyelitis is 3-6 days. For the onset of paralysis in paralytic poliomyelitis, the incubation period usually is 7 to 21 days.

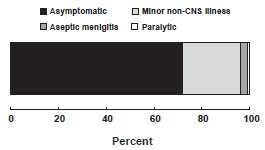

The response to poliovirus infection is highly variable and has been categorized on the basis of the severity of clinical presentation.

Up to 72% of all polio infections in children are asymptomatic. Infected persons without symptoms shed virus in the stool and are able to transmit the virus to others.

Approximately 24% of polio infections in children consist of a minor, nonspecific illness without clinical or laboratory evidence of central nervous system invasion. This clinical presentation is known as abortive poliomyelitis, and is characterized by complete recovery in less than a week. This is characterized by a low grade fever and sore throat.

Nonparalytic aseptic meningitis (symptoms of stiffness of the neck, back, and/or legs), usually following several days after a prodrome similar to that of minor illness, occurs in 1%–5% of polio infections in children. Increased or abnormal sensations can also occur. Typically these symptoms will last from 2 to 10 days, followed by complete recovery.

Outcomes of poliovirus infection

Fewer than 1% of all polio infections in children result in flaccid paralysis. Paralytic symptoms generally begin 1 to 18 days after prodromal symptoms and progress for 2 to 3 days. Generally, no further paralysis occurs after the temperature returns to normal. The prodrome may be biphasic, especially in children, with initial minor symptoms separated by a 1- to 7-day period from more major symptoms. Additional prodromal signs and symptoms can include a loss of superficial reflexes, initially increased deep tendon reflexes and severe muscle aches and spasms in the limbs or back. The illness progresses to flaccid paralysis with diminished deep tendon reflexes, reaches a plateau without change for days to weeks, and is usually asymmetrical. Strength then begins to return. Patients do not experience sensory losses or changes in cognition.

Many persons with paralytic poliomyelitis recover completely and, in most, muscle function returns to some degree. Weakness or paralysis still present 12 months after onset is usually permanent.

Paralytic polio is classified into three types, depending on the level of involvement. Spinal polio is most common, and during 1969–1979, accounted for 79% of paralytic cases. It is characterized by asymmetric paralysis that most often involves the legs. Bulbar polio leads to weakness of muscles innervated by cranial nerves and accounted for 2% of cases during this period. Bulbospinal polio, a combination of bulbar and spinal paralysis, accounted for 19% of cases.

The death-to-case ratio for paralytic polio is generally 2%–5% among children and up to 15%–30% for adults (depending on age). It increases to 25%–75% with bulbar involvement.

Laboratory Testing

Viral Isolation

Poliovirus may be recovered from the stool, is less likely recovered from the pharynx, and only rarely recovered from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or blood. If poliovirus is isolated from a person with acute flaccid paralysis, it must be tested further, using reverse transcriptase - polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or genomic sequencing, to determine if the virus is “wild type” (that is, the virus that causes polio disease) or vaccine type (virus that could derive from a vaccine strain).

Serology

Serology may be helpful in establishing a diagnosis of disease if obtained early in the course of disease. Two specimens are needed, one early in the course of the illness and another three weeks later. A four-fold rise in the titer suggests poliovirus infection. Two specimens in which no antibody is detected may rule out poliovirus infection. There are limitations to antibody titers. Patients who are immunocompromised may have two titers with no antibody detected and still be infected with poliovirus. For any patient, neutralizing antibodies appear early and may be at high levels by the time the patient is hospitalized; therefore, a four-fold rise in antibody titer may not be demonstrated. Someone who has been vaccinated and does not have poliovirus infection may have a specimen with detectable antibody from the vaccine.

Poliovirus Epidemiology

- Reservoir

- Human

- Transmission

- Fecal-oral

- Oral-oral possible

- Communicability

- most infectious 7-10 days before and after onset of symptoms

- Virus present in stool 3 to 6 weeks

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

In poliovirus infection, the CSF usually contains an increased number of white blood cells (10–200 cells/mm3, primarily lymphocytes) and a mildly elevated protein (40–50 mg/100 mL).

Epidemiology

Occurrence

At one time poliovirus infection occurred throughout the world. Transmission of wild poliovirus was interrupted in the United States in 1979 or possibly earlier. A polio eradication program conducted by the Pan American Health Organization led to elimination of polio in the Western Hemisphere in 1991. The Global Polio Eradication Program has dramatically reduced poliovirus transmission throughout the world. In 2012, only 223 confirmed cases of polio were reported globally and polio was endemic only in three countries.

Reservoir

Humans are the only known reservoir of poliovirus, which is transmitted most frequently by persons with inapparent infections. There is no asymptomatic carrier state except in immune deficient persons.

Transmission

Person-to-person spread of poliovirus via the fecal-oral route is the most important route of transmission, although the oral-oral route is possible.

Temporal Pattern

Poliovirus infection typically peaks in the summer months in temperate climates. There is no seasonal pattern in tropical climates.

Communicability

Poliovirus is highly infectious, with seroconversion rates among susceptible household contacts of children nearly 100%, and greater than 90% among susceptible household contacts of adults. Persons infected with poliovirus are most infectious from 7 to 10 days before and after the onset of symptoms, but poliovirus may be present in the stool from 3 to 6 weeks.

Secular Trends in the United States

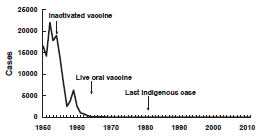

Poliomyelitis - United States, 1950-2011

Source: National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, CDC

Before the 18th century, polioviruses probably circulated widely. Initial infections with at least one type probably occurred in early infancy, when transplacentally acquired maternal antibodies were high. Exposure throughout life probably provided continual boosting of immunity, and paralytic infections were probably rare. (This view has been challenged based on data from lameness studies in developing countries).

In the immediate prevaccine era, improved sanitation allowed less frequent exposure and increased the age of primary infection. Boosting of immunity from natural exposure became more infrequent and the number of susceptible persons accumulated, ultimately resulting in the occurrence of epidemics, with 13,000 to 20,000 paralytic cases reported annually.

In the early vaccine era, the incidence dramatically decreased after the introduction of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) in 1955. The decline continued following oral polio vaccine (OPV) introduction in 1961. In 1960, a total of 2,525 paralytic cases were reported, compared with 61 in 1965.

The last cases of paralytic poliomyelitis caused by endemic transmission of wild virus in the United States were in 1979, when an outbreak occurred among the Amish in several Midwest states. The virus was imported from the Netherlands.

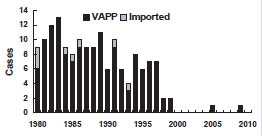

Poliomyelitis - United States, 1980-2010

Poliovirus Vaccine

- 1955 - Inactivated vaccine

- 1961 - Types 1 and 2 monovalent OPV

- 1962 - Type 3 monovalent OPV

- 1963 - Trivalent OPV

- 1987 - Enhanced-potency IPV (IPV)

Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV)

- Contains 3 serotypes of vaccine virus

- Grown on monkey kidney (Vero) cells

- Inactivated with formaldehyde

- Contains 2-phenoxyethanol, neomycin, streptomycin, polymyxin B

From 1980 through 1999, a total of 162 confirmed cases of paralytic poliomyelitis were reported, an average of 8 cases per year. Six cases were acquired outside the United States and imported. The last imported case was reported in 1993. Two cases were classified as indeterminant (no poliovirus isolated from samples obtained from the patients, and patients had no history of recent vaccination or direct contact with a vaccine recipient). The remaining 154 (95%) cases were vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) caused by live oral polio vaccine.

In order to eliminate VAPP from the United States, ACIP recommended in 2000 that IPV be used exclusively in the United States. The last case of VAPP acquired in the United States was reported in 1999. In 2005, an unvaccinated U.S. resident was infected with polio vaccine virus in Costa Rica and subsequently developed VAPP. A second case of VAPP from vaccine-derived poliovirus in a person with long-standing combined immunodeficiency was reported in 2009. The patient was probably infected approximately 12 years prior to the onset of paralysis. Also in 2005, several asymptomatic infections with a vaccine-derived poliovirus were detected in unvaccinated children in Minnesota. The source of the vaccine virus has not been determined, but it appeared to have been circulating among humans for at least 2 years based on genetic changes in the virus. No VAPP has been reported from this virus.

Poliovirus Vaccines

Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) was licensed in 1955 and was used extensively from that time until the early 1960s. In 1961, type 1 and 2 monovalent oral poliovirus vaccine (MOPV) was licensed, and in 1962, type 3 MOPV was licensed. In 1963, trivalent OPV was licensed and largely replaced IPV use. Trivalent OPV was the vaccine of choice in the United States and most other countries of the world after its introduction in 1963. An enhanced-potency IPV was licensed in November 1987 and first became available in 1988. Use of OPV was discontinued in the United States in 2000.

Characteristics

Inactivated poliovirus vaccine

Two enhanced forms of inactivated poliovirus vaccine are currently licensed in the U.S., but only one vaccine (IPOL, sanofi pasteur) is actually distributed. This vaccine contains all three serotypes of polio vaccine virus. For sanofi’s single component vaccine the viruses are grown in a type of monkey kidney tissue culture (Vero cell line) and inactivated with formaldehyde. The vaccine contains 2-phenoxyethanol as a preservative, and trace amounts of neomycin, streptomycin, and polymyxin B. It is supplied in a single-dose prefilled syringe and should be administered by either subcutaneous or intramuscular injection. For sanofi’s combination DTaP-IPV/Hib vaccine (Pentacel) the IPV component is grown in a human diploid cell line and does not contain 2-phenoxyethanol at preservative level concentrations. GlaxoSmithKline’s combination vaccine DTaP-IPV (Kinrix) uses IPV grown in the Vero cell line. Kinrix does not contain any preservative.

Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV)

- Contains 3 serotypes of vaccine virus

- Grown on monkey kidney (Vero) cells

- Contains neomycin and streptomycin

- Shed in stool for up to 6 weeks following vaccination

Oral poliovirus vaccine (not available in the United States)

Trivalent OPV contains live attenuated strains of all three serotypes of poliovirus in a 10:1:3 ratio. The vaccine viruses are grown in monkey kidney tissue culture (Vero cell line). The vaccine is supplied as a single 0.5-mL dose in a plastic dispenser. The vaccine contains trace amounts of neomycin and streptomycin. OPV does not contain a preservative.

Live attenuated polioviruses replicate in the intestinal mucosa and lymphoid cells and in lymph nodes that drain the intestine. Vaccine viruses are excreted in the stool of the vaccinated person for up to 6 weeks after a dose. Maximum viral shedding occurs in the first 1–2 weeks after vaccination, particularly after the first dose.

Vaccine viruses may spread from the recipient to contacts. Persons coming in contact with fecal material of a vaccinated person may be exposed and infected with vaccine virus.

Immunogenicity and Vaccine Efficacy

IPV Efficacy

- Highly effective in producing immunity to poliovirus

- 90% or more immune after 2 doses

- At least 99% immune after 3 doses

- Duration of immunity not known with certainty

OPV Efficacy

- Highly effective in producing immunity to poliovirus

- Approximately 50% immune after 1 dose

- More than 95% immune after 3 doses

- Immunity probably lifelong

Polio Vaccination Recommendations, 1996-1999

- Increased use of IPV (sequential IPV-OPV schedule) recommended in 1996

- Intended to reduce the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP)

- Continued risk of VAPP for contacts of OPV recipients

Inactivated poliovirus vaccine

IPV is highly effective in producing immunity to poliovirus and protection from paralytic poliomyelitis. Ninety percent or more of vaccine recipients develop protective antibody to all three poliovirus types after two doses, and at least 99% are immune following three doses. Protection against paralytic disease correlates with the presence of antibody.

IPV appears to produce less local gastrointestinal immunity than does OPV, so persons who receive IPV are more readily infected with wild poliovirus than OPV recipients.

The duration of immunity with IPV is not known with certainty, although it probably provides protection for many years after a complete series.

Oral poliovirus vaccine

OPV is highly effective in producing immunity to poliovirus. A single dose of OPV produces immunity to all three vaccine viruses in approximately 50% of recipients. Three doses produce immunity to all three poliovirus types in more than 95% of recipients. As with other live-virus vaccines, immunity from oral poliovirus vaccine is probably lifelong. OPV produces excellent intestinal immunity, which helps prevent infection with wild virus.

Serologic studies have shown that seroconversion following three doses of either IPV or OPV is nearly 100% to all three vaccine viruses. However, seroconversion rates after three doses of a combination of IPV and OPV are lower, particularly to type 3 vaccine virus (as low as 85% in one study). A fourth dose (most studies used OPV as the fourth dose) usually produces seroconversion rates similar to three doses of either IPV or OPV.

Vaccination Schedule and Use

Polio Vaccination Recommendations

- Exclusive use of IPV recommended in 2000

- OPV no longer routinely available in the United States

- Indigenous VAPP eliminated

Polio Vaccination Schedule

| Age | Vaccine | Minimum Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 2 months | IPV | -- |

| 4 months | IPV | 4 weeks |

| 6-18 months | IPV | 4 weeks |

| 4-6 years | IPV | 6 months |

Trivalent OPV was the vaccine of choice in the United States (and most other countries of the world) since it was licensed in 1963. The nearly exclusive use of OPV led to elimination of wild-type poliovirus from the United States in less than 20 years. However, one case of VAPP occurred for every 2 to 3 million doses of OPV administered, which resulted in 8 to 10 cases of VAPP each year in the United States (see Adverse Events section for more details on VAPP). From 1980 through 1999, VAPP accounted for 95% of all cases of paralytic poliomyelitis reported in the United States.

In 1996, ACIP recommended an increase in use of IPV through a sequential schedule of IPV followed by OPV. This recommendation was intended to reduce the occurrence of vaccine-associated paralytic polio. The sequential schedule was expected to eliminate VAPP among vaccine recipients by producing humoral immunity to polio vaccine viruses with inactivated polio vaccine prior to exposure to live vaccine virus. Since OPV was still used for the third and fourth doses of the polio vaccination schedule, a risk of VAPP would continue to exist among contacts of vaccinees, who were exposed to live vaccine virus in the stool of vaccine recipients.

The sequential IPV–OPV polio vaccination schedule was widely accepted by both providers and parents. Fewer cases of VAPP were reported in 1998 and 1999, suggesting an impact of the increased use of IPV. However, only the complete discontinuation of use of OPV would lead to complete elimination of VAPP. To further the goal of complete elimination of paralytic polio in the United States, ACIP recommended in July 1999 that inactivated polio vaccine be used exclusively in the United States beginning in 2000. OPV is no longer routinely available in the United States. Exclusive use of IPV eliminated the shedding of live vaccine virus, and eliminated any indigenous VAPP.

A primary series of IPV consists of three doses. In infancy, these primary doses are integrated with the administration of other routinely administered vaccines. The first dose may be given as early as 6 weeks of age but is usually given at 2 months of age, with a second dose at 4 months of age. The third dose should be given at 6–18 months of age. The recommended interval between the primary series doses is 2 months. However, if accelerated protection is needed, the minimum interval between each of the first 3 doses of IPV is 4 weeks.

Schedules That Include Both IPV and OPV

- Only IPV is available in the United States

- Schedule begun with OPV should be completed with IPV

- Any combination of 4 doses of IPV and OPV by 4-6 years of age constitutes a complete series

Combination Vaccines That Contain IPV

- Pediarix

- DTaP, Hepatitis B and IPV

- Kinrix

- DTaP and IPV

- Pentacel

- .DTaP, Hib and IPV

Polio Vaccination of Adults

- Routine vaccination of U.S. residents 18 years of age and older not necessary or recommended

- May consider vaccination of travelers to polio-endemic countries and selected laboratory workers

The final dose in the IPV series should be administered at 4 years of age or older. A dose of IPV on or after age 4 years is recommended regardless of the number of previous doses. The minimum interval from the next-to-last to final dose is 6 months.

When DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel) is used to provide 4 doses at ages 2, 4, 6, and 15-18 months, an additional booster dose of age-appropriate IPV-containing vaccine (IPV or DTaP-IPV [Kinrix]) should be administered at age 4-6 years. This will result in a 5-dose IPV vaccine series, which is considered acceptable by ACIP. DTaP-IPV/Hib is not indicated for the booster dose at 4-6 years of age. ACIP recommends that the minimum interval from dose 4 to dose 5 should be at least 6 months to provide an optimum booster response.

Shorter intervals between doses and beginning the series at a younger age may lead to lower seroconversion rates. Consequently, ACIP recommends the use of the minimum age (6 weeks) and minimum intervals between doses in the first 6 months of life only if the vaccine recipient is at risk for imminent exposure to circulating poliovirus (e.g., during an outbreak or because of travel to a polio-endemic region).

Only IPV is available for routine polio vaccination of children in the United States. A polio vaccination schedule begun with OPV should be completed with IPV. If a child receives both types of vaccine, four doses of any combination of IPV or OPV by 4–6 years of age is considered a complete poliovirus vaccination series. The last dose should be given after the fourth birthday. A minimum interval of 4 weeks should separate all doses of the series, with the exception that if dose three and dose four are both IPV, the interval between these two doses should be six months.

There are three combination vaccines that contain inactivated polio vaccine. Pediarix is produced by GlaxoSmithKline and contains DTaP, hepatitis B and IPV vaccines. Pediarix is licensed for the first 3 doses of the DTaP series among children 6 weeks through 6 years of age. Kinrix is also produced by GSK and contains DTaP and IPV. Kinrix is licensed only for the fifth dose of DTaP and fourth dose of IPV among children 4 through 6 years of age. Pentacel is produced by sanofi pasteur and contains DTaP, Hib and IPV. It is licensed for the first four doses of the component vaccines among children 6 weeks through 4 years of age. Pentacel is not licensed for children 5 years or older. Additional information about these combination vaccines is in the Pertussis chapter of this book.

Polio Vaccination of Adults

Polio Vaccination of Unvaccinated Adults

- Use standard IPV schedule if possible (0, 1-2 months, 6-12 months)

- May separate first and second doses by 4 weeks if accelerated schedule needed

- The minimum interval between the second and third doses is 6 months

Polio Vaccination of Previously Vaccinated Adults

- Previously complete series

- administer one dose of IPV

- Incomplete series

- administer remaining doses in series

- no need to restart series

Routine vaccination of adults (18 years of age and older) who reside in the United States is not necessary or recommended because most adults are already immune and have a very small risk of exposure to wild poliovirus in the United States.

Some adults, however, are at increased risk of infection with poliovirus. These include travelers to areas where poliomyelitis is endemic or epidemic (see CDC Health Information for International Travel 2014 (the Yellow Book) for specific regions), and laboratory workers handling specimens that may contain polioviruses.

Recommendations for poliovirus vaccination of adults in the above categories depend upon the previous vaccination history and the time available before protection is required.

For unvaccinated adults (including adults without a written record of prior polio vaccination) at increased risk of exposure to poliomyelitis, primary immunization with IPV is recommended. The recommended schedule is two doses separated by 1 to 2 months, and a third dose given 6 to 12 months after the second dose. The minimum interval between the second and the third doses is 6 months.

In some circumstances time will not allow completion of this schedule. If 8 weeks or more are available before protection is needed, three doses of IPV should be given at least 4 weeks apart. If 4 to 8 weeks are available before protection is needed, two doses of IPV should be given at least 4 weeks apart. If less than 4 weeks are available before protection is needed, a single dose of IPV is recommended. In all instances, the remaining doses of vaccine should be given later, at the recommended intervals, if the person remains at increased risk.

Adults who have previously completed a primary series of 3 or more doses and who are at increased risk of exposure to poliomyelitis should receive one dose of IPV. The need for further supplementary doses has not been established. Only one supplemental dose of polio vaccine is recommended for adults who have received a complete series (i.e., it is not necessary to administer additional doses for subsequent travel to a polio endemic country).

Adults who have previously received less than a full primary course of OPV or IPV and who are at increased risk of exposure to poliomyelitis should be given the remaining doses of IPV, regardless of the interval since the last dose and type of vaccine previously received. It is not necessary to restart the series of either vaccine if the schedule has been interrupted.

Contraindications and Precautions to Vaccination

Polio Vaccine Contraindications and Precautions

- Severe allergic reaction to a vaccine component or following a prior dose of vaccine

- Moderate or severe acute illness

Severe allergic reaction (e.g. anaphylaxis) to a vaccine component, or following a prior dose of vaccine, is a contraindication to further doses of that vaccine. Since IPV contains trace amounts of streptomycin, neomycin, and polymyxin B, there is a possibility of allergic reactions in persons sensitive to these antibiotics. Persons with allergies that are not anaphylactic, such as skin contact sensitivity, may be vaccinated.

Persons with a moderate or severe acute illness normally should not be vaccinated until their symptoms have decreased.

Breastfeeding does not interfere with successful immunization against poliomyelitis with IPV. IPV may be administered to a child with diarrhea. Minor upper respiratory illnesses with or without fever, mild to moderate local reactions to a prior dose of vaccine, current antimicrobial therapy, and the convalescent phase of an acute illness are not contraindications for vaccination with IPV.

Contraindications to combination vaccines that contain IPV are the same as the contraindications to the individual components (e.g., DTaP, hepatitis B).

Adverse Reactions Following Vaccination

Polio Vaccine Adverse Reactions

- Local reactions (IPV)

- Paralytic poliomyelitis (OPV)

Minor local reactions (pain, redness) most commonly occur following IPV. Because IPV contains trace amounts of streptomycin, polymyxin B, and neomycin, allergic reactions may occur in persons allergic to these antibiotics.

Vaccine-Associated Paralytic Poliomyelitis

Vaccine-associated paralytic polio is a rare adverse event following live oral poliovirus vaccine. Inactivated poliovirus vaccine does not contain live virus, so it cannot cause VAPP. The mechanism of VAPP is believed to be a mutation, or reversion, of the vaccine virus to a more neurotropic form. These mutated viruses are called revertants. Reversion is believed to occur in almost all vaccine recipients, but it only rarely results in paralytic disease. The paralysis that results is identical to that caused by wild virus, and may be permanent.

Vaccine-Associated Paralytic Poliomyelitis

- More likely in persons 18 years of age and older

- Much more likely in persons with immunodeficiency

- No procedure available for identifying persons at risk of paralytic disease

The risk of VAPP is not equal for all OPV doses in the vaccination series. The risk of VAPP is 7 to 21 times higher for the first dose than for any other dose in the OPV series. VAPP is more likely to occur in persons 18 years of age and older than in children, and is much more likely to occur in immunodeficient children than in those who are immunocompetent. Compared with immunocompetent children, the risk of VAPP is almost 7,000 times higher for persons with certain types of immunodeficiencies, particularly B-lymphocyte disorders (e.g., agammaglobulinemia and hypogammaglobulinemia), which reduce the synthesis of immune globulins. There is no procedure available for identifying persons at risk of paralytic disease, except excluding older persons and screening for immunodeficiency.

From 1980 through 1999, 162 cases of paralytic polio were reported in the United States; 2 cases were indeterminate as to source, and 154 (95%) of these cases were VAPP, and the remaining six were in persons who acquired documented or presumed wild-virus polio outside the United States. Some cases occurred in vaccine recipients and some cases occurred in contacts of vaccine recipients. None of the vaccine recipients were known to be immunologically abnormal prior to vaccination. Since 1999, only 2 cases of VAPP have been reported in the United States: one acquired outside the United States and one who likely was infected prior to the cessation of OPV in the United States.

Vaccine Storage and Handling

Polio vaccine should be maintained at refrigerator temperature between 35°F and 46°F (2°C and 8°C). Manufacturer package inserts contain additional information. For complete information on best practices and recommendations please refer to CDC’s Vaccine Storage and Handling Toolkit [4.33 MB, 109 pages].

Outbreak Investigation and Control

Collect preliminary clinical and epidemiologic information (including vaccine history and contact with OPV vaccines) on any suspected case of paralytic polio. Notify CDC, (Emergency Operations Center (EOC), 770-488-7100). Follow-up should occur in close collaboration with local and state health authorities. Paralytic polio is designated “immediately notifiable, extremely urgent”, requiring state and local health authorities to notify CDC within 4 hours of their notification. Non-paralytic polio is designated “immediately notifiable and urgent” requiring state and local health authorities to notify CDC within 24 hours of their notification. CDC’s EOC will provide consultation regarding the collection of appropriate clinical specimens for virus isolation and serology, the initiation of appropriate consultations and procedures to rule out or confirm poliomyelitis, the compilation of medical records, and most importantly, the evaluation of the likelihood that the disease may be caused by wild poliovirus.

Polio Eradication

Polio Eradication

- Last case in United States in 1979

- Western Hemisphere certified polio free in 1994

- Last isolate of type 2 poliovirus in India in October 1999

- Global eradication goal

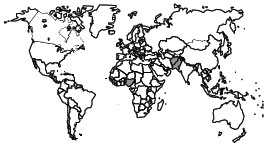

Wild Poliovirus 1988

Wild Poliovirus 2012

Following the widespread use of poliovirus vaccine in the mid-1950s, the incidence of poliomyelitis declined rapidly in many industrialized countries. In the United States, the number of cases of paralytic poliomyelitis reported annually declined from more than 20,000 cases in 1952 to fewer than 100 cases in the mid-1960s. The last documented indigenous transmission of wild poliovirus in the United States was in 1979.

In 1985, the member countries of the Pan American Health Organization adopted the goal of eliminating poliomyelitis from the Western Hemisphere by 1990. The strategy to achieve this goal included increasing vaccination coverage; enhancing surveillance for suspected cases (i.e., surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis); and using supplemental immunization strategies such as national immunization days, house-to-house vaccination, and containment activities. Since 1991, when the last wild-virus–associated indigenous case was reported from Peru, no additional cases of poliomyelitis have been confirmed despite intensive surveillance. In September 1994, an international commission certified the Western Hemisphere to be free of indigenous wild poliovirus. The commission based its judgment on detailed reports from national certification commissions that had been convened in every country in the region.

In 1988, the World Health Assembly (the governing body of the World Health Organization) adopted the goal of global eradication of poliovirus by the year 2000. Although this goal was not achieved, substantial progress has been made. In 1988, an estimated 350,000 cases of paralytic polio occurred, and the disease was endemic in more than 125 countries. By 2012, only 223 cases were reported globally—a reduction of more than 99% from 1988—and polio remained endemic in only three countries. In addition, one type of poliovirus appears to have already been eradicated. The last isolation of type 2 virus was in India in October 1999.

The polio eradication initiative is led by a coalition of international organizations that includes WHO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), CDC, and Rotary International. Other bilateral and multilateral organizations also support the initiative. Rotary International has contributed more than $600 million to support the eradication initiative. Current information on the status of the global polio eradication initiative is available on the World Health Organization.

Post-polio Syndrome

After an interval of 15–40 years, 25%–40% of persons who contracted paralytic poliomyelitis in childhood experience new muscle pain and exacerbation of existing weakness, or develop new weakness or paralysis. This disease entity is referred to as post-polio syndrome. Factors that increase the risk of post-polio syndrome include increasing length of time since acute poliovirus infection, presence of permanent residual impairment after recovery from the acute illness, and female sex. The pathogenesis of post-polio syndrome is thought to involve the failure of oversized motor units created during the recovery process of paralytic poliomyelitis. Post-polio syndrome is not an infectious process, and persons experiencing the syndrome do not shed poliovirus.

For more information, or for support for persons with post-polio syndrome and their families, contact:

Post-Polio Health International

4207 Lindell Boulevard #110

St. Louis, MO 63108-2915

314-534-0475

info@post-polio.org

Acknowledgment

The editors thank Drs. Greg Wallace, and Jim Alexander, CDC for their assistance in updating this chapter.

Selected References

- CDC. Imported vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis—United States, 2005. MMWR 2006;55:97–9.

- CDC.. Tracking Progress Toward Global Polio Eradication — Worldwide, 2009–2010. MMWR 2011;60(No. 14):441-5.

- CDC. Poliomyelitis prevention in the United States: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. (ACIP). MMWR 2000;49 (No. RR-5):1–22.

- CDC. Apparent global interruption of wild poliovirus type 2 transmission. MMWR 2001;50:222–4.

- CDC. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) regarding routine poliovirus vaccination. MMWR 2009;58 (No. 30):829–30.

- Page last reviewed: November 15, 2016

- Page last updated: September 29, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir