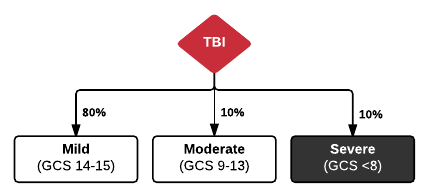

Severe traumatic brain injury

Contents

Background

Head trauma associated with severely depressed GCS (≤ 8). Accounts for approximately 10% of traumatic brain injury.

Clinical Features

History and physical examination often severely limited.

History

If collateral can be obtained, note presence of coagulopathy.

Physical Examination

- Calculate GCS

- Pupils: may identify herniation syndromes

- Motor

- Focus on symmetry as hemiparesis may suggest herniation syndrome

- Elicit movement with noxious stimuli in non-cooperative patients

- Note voluntary or purposeful movement (crossing the midline, approaching the stimulus, pushing the examiner's hand away)

- Cranial Nerves

- Assessable cranial nerves: pupils (III), corneal (V, VII), gag (IX, X), VOR (VII, VI)

- Reflexes

- Plantar extensor response: non-specific, delineates disruption along corticospinal tract (cortex to LMN)

Differential Diagnosis

Intracranial Hemorrhage

- Intra-axial

- Hemorrhagic stroke (Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage)

- Traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage

- Extra-axial

- Epidural hemorrhage

- Subdural hemorrhage

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (aneurysmal intracranial hemorrhage)

Maxillofacial Trauma

- Le Fort fractures

- Skull fracture (peds)

- Auricular hematoma

- Nasal fracture

- Zygomatic arch fracture

- Zygomaticomaxillary (tripod) fracture

- Dental trauma

- Mandible fracture

Orbital trauma

Acute

- Ruptured Globe^

- Corneal Abrasion

- Ocular foreign body

- Conjunctival laceration

- Caustic Keratoconjunctivitis^^

- Subconjunctival hemorrhage

- Traumatic iritis

- Traumatic hyphema

- Retinal detachment

- Retrobulbar hemorrhage/hematoma

- Traumatic mydriasis

- Orbital fracture

- Frontal sinus fracture

- Naso-ethmoid fracture

- Inferior orbial wall fracture

- Medial orbital wall fracture

Subacute/Delayed

Blunt Neck Trauma

- Spinal cord trauma

- Vertebral and carotid artery dissection

- Whiplash injury

- Cervical spine fractures and dislocations

- Strangulation

Evaluation

Imaging modality of choice is non-contrast head (cranial) computed tomography, obtained emergently.

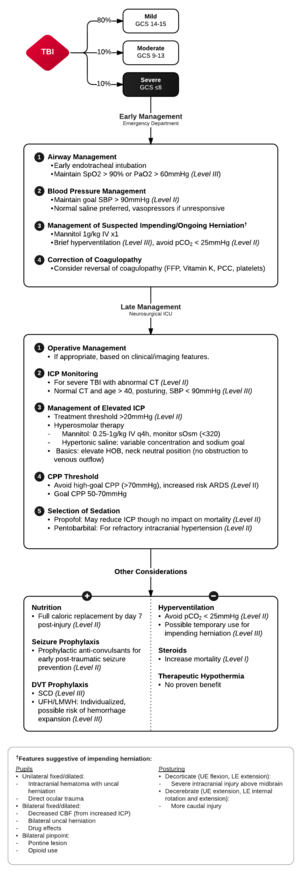

Management

Critical aspects of management related to minimizing secondary injury, primarily through the avoidance of hypoxia and hypotension - both of which are significantly associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Airway

- Avoid hypoxia (SpO2 <90%, PaO2 <60mmHg)

- Early endotracheal intubation is indicated.

- Pre-oxygenation: Hyperoxia in TBI can be harmful[1], however it can be assumed that resumption of targeting normoxemia immediately after securing airway control outweighs the potential harm of hypoxia during intubation (which can often be challenging in these settings due to maxillofacial trauma and maintenance of cervical spine precautions).

- Pre-treatment: No clear benefit to use of lidocaine to blunt reflex sympathetic response to laryngoscopy[2]. Short acting opioids can be considered in hemodynamically stable patients[3].

- Induction: Selection of induction agent remains controversial. Etomidate is well-studied with a stable hemodynamic profile. Ketamine which has shown promise in some trials due to its hemodynamic profile (commonly increased MAP and subsequently CPP) without previously-cited deleterious effects on ICP and may be the agent of choice for patients with hemodynamic compromise[4] [5].

- Paralysis: No apparent benefit to the addition of a defasciculating dose of non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent (to prevent transient elevation of intracranial pressure associated with widespread muscle fasciculation)[6].

Breathing

- Avoid hyperventilation as hypocapnia induces cerebral vasoconstriction, target low-normal PCO2 of 35mmHg.

Circulation

- Avoid hypotension (SBP <90mmHg)

- Fluid resuscitation with isotonic saline, and vasopressors if refractory.

- Albumin should be avoided[7].

- There is no apparent benefit to the initial administration of hypertonic saline[8] [9].

Management of Impending Herniation

Hyperosmolar therapy is indicated for patients with objective elevations of intracranial pressure or signs of impending or ongoing herniation.

- Both hypertonic saline and mannitol are effective at reducing intracranial pressure[10].

- Meta-analyses of limited and variable data suggest benefit towards hypertonic saline[11].

Increased ICP Treatment[12]

Head of Bed elevation

- 30 degrees or reverse Trendelenburg will lower ICP[13]

- Keep head and neck in neutral position, improving cerebral venous drainage

- Avoid compressing IVJ or EVJ with tight C-collars or fixation of ETT

Maintain cerebral perfusion

- CPP = MAP-ICP

- If MAP <80, then CPP<60

- Ultimately no Class 1 evidence for optimal CPP

- Transfuse PRBCs with goal Hb > 10 mg/dL in severe TBI[14]

- Provide fluids and vasopressors if needed for goal cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) of 70-80 mmHg[15][16][17]

- Mortality increases 20% for each 10 mmHg loss of CPP

- Avoid dips in CPP < 70 mmHg, which is associated with cerebral ischemia and glutamate increase[18]

- Vasopressors

- Phenylephrine increases CPP without increasing ICP in animal models[19][20]

- May be beneficial when patient is tachycardic (reflex bradycardia), but avoid phenylephrine if patient is already bradycardic (Cushing's reflex)

- Phenylephrine may be associated with less cell injury as compared to norepinephrine in TBI[21]

- IV fluids[22]

- Maintain euvolemia, initially resuscitate with Normal Saline

- Then consider hypertonic saline and/or mannitol

- Do not use free water, low osmolal, dextrose-alone solutions, and colloids

- Do not use Ringer's lactate as it is slightly hypotonic

- Prefer NS over D5-NS if possible, but D5-NS may be necessary to avoid hypoglycemia, especially in younger pediatric patients

- Correction of severe hypernatremia > 160 mmol/L (hypothalamic-pituitary injury, diabetes insipidus) should be gradual to not worsen cerebral edema

Osmotherapies

Therapies include either mannitol or hypertonic saline. In choosing the appropriate agent, coordinate with neurosurgery and take into account the patient's blood pressure. Mannitol may cause hypotension due to the osmotic diuresis.

- Mannitol[23]

- If SBP > 90 mmHg

- Bolus 20% at 0.25-1 gm/kg as rapid infusion over 15-20 min

- Target Osm 300-320 mOsm/kg

- Reduces ICP within 30min, duration of action of 6-8hr

- Monitor I/O to maintain euvolemia during expected diuresis and use normal saline to volume replace

- Do not use continuous infusions, as mannitol crosses the BBB after prolonged administration and contributes to cerebral edema

- Consider hypertonic saline for further boluses

- Hypertonic saline has higher osmotic gradient and is less permeable across BBB than mannitol

- Hypertonic saline may be more effective than mannitol, current standard of care[24]

- Obtain baseline serum osmolarity and sodium

- Most studies used 250 mL bolus of 7.5% saline with dextran[25]

- Initial 250 cc bolus of 3% will reduce ICP and can be delivered through a peripheral line

- Target sodium 145-155 mmol/dL

Prevent Cerebral Vasoconstriction

- Hyperventilation does not improve mortality, used only as temporizing measure

- Should only be used if reduction in ICP necessary without any other means or ICP elevation refractory to all other treatments:

- Sedation

- Paralytics

- CSF drainage

- Hypertonic saline, osmotic diuretics

- Maintain PaCO2 35-40 mmHg for only up to 30 minutes, no longer if it can be avoided[26]

- Hyperventilation to PaCO2 < 30 mmHg not indicated, and decreases cerebral blood flow to ischemic levels[27][28]

Seizure Control

- Treat immediately with benzodiazepines and antiepileptic drugs (AEDs)

- Consider propofol for post-intubation sedation

- Seizure prophylaxis reduces seizures but does not improve long-term outcomes[29]

- AEDs prevent early seizures (which occur between 24 hrs - 7 days), with NNT = 10 by Cochrane Review[30]

- Risk factors for post-traumatic seizures:

- GCS < 10 initially

- Cortical contusion

- Depressed skull fx

- Subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage or ICH

- Penetrating head injury

- Seizure within 24 hours of injury (immediate seizure)

- Treat any clinically apparent and EEG confirmed seizures

- Consider prophylaxis in patients with any risk factors as above

- Phenytoin or fosphenytoin first line agent by BTF guidelines[31]

- Load 20 PE/kg IV, then 100 PE IV q8hrs for 7 days

- Measure serum levels to titrate to therapeutic levels

- Levetiracetam may be used as alternative[32]

- 20 mg/kg load IV, followed by 1000 mg IV q12h for 7 days

- Levetiracetam may have less frequent and severe adverse drug side effects events as compared to phenytoin

Intubation Pretreatment

Goal cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) ~70mmHg

- If need for RSI, consider pretreatment with lidocaine and/or fentanyl

- Also ensure adequate sedation (prevent gag reflex)

- Etomidate may cause adrenal insufficiency especially in head injured patients, so consider hydrocortisone if refractory hypotension post-intubation[33]

Decrease metabolic rate

- Provide adequate sedation and analgesia

- Avoid HYPERthermia and treat fever aggressively

- However, hypothermia is not a necessary goal

- Moderate hypothermia 32°C to 34°C controversial, large RCT showed no effect[34]

Other Critical Care Measures

- DVT prophylaxis with SCDs, no anticoagulation

- Stress ulcer prophylaxis with H2-blocker/PPI and sucralfate to avoid Cushing's ulcers

- Good glycemic control, but tight maintenance not supported[35]

- Steroids, methylprednisolone contraindicated in severe TBI (risk of death increased in CRASH 2004 trial)[36]

- Routine paralysis not indicated[37]

- Increased risk of pneumonia and ICU length of stay

- However, may be used for refractory ICP elevation

Barbituate Coma[38]

- For ICP refractory to maximal medical and surgical therapy

- Only for hemodynamically stable patients

- Induce with the following:

- Pentobarbital 10 mg/kg over 30 min

- Then 5 mg/kg/hr for 3 hrs

- Followed by 1 mg/kg/hr

Guidelines for Neurosurgical Intervention

- Intracranial pressure monitoring is indicated for salvageable patients with severe TBI and abnormal CT (hematoma, contusion, swelling, herniation, compressed basal cisterns)[39]

- Surgical intervention/evacuation is indicated for:

- Epidural Hematoma: volume >30mL or any with GCS <8 or anisocoria[40]

- Subdural Hematoma: >10mm width with >5mm of midline shift, any with GCS <8 or decline >2[41]

- Posterior Fossa Hemorrhage: if mass effect (distortion of 4th ventricle, obstructive hydrocephalus)[42]

- Depressed Skull Fracture: depth > thickness of cranium, dural penetration, pneumocephalus[43]

Disposition

Generally warrant admission to a surgical intensive care unit.

See Also

External Links

References

- ↑ Brenner M, Stein D, Hu P, Kufera J, Wooford M, Scalea T. Association Between Early Hyperoxia and Worse Outcomes After Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Surg. 2012;147(11):1042–5. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2012.1560.

- ↑ Butler J, Jackson R, Mackway-Jones K. Lignocaine premedication before rapid sequence induction in head injuries. Emergency medicine journal. 2002.

- ↑ Chung KS, Sinatra RS, Halevy JD, Paige D, Silverman DG. A comparison of fentanyl, esmolol, and their combination for blunting the haemodynamic responses during rapid-sequence induction. Can J Anaesth. 1992;39(8):774–779. doi:10.1007/BF03008287.

- ↑ Sehdev RS, Symmons DA, Kindl K. Ketamine for rapid sequence induction in patients with head injury in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18(1):37–44. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00802.x.

- ↑ Hughes S. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. BET 3: is ketamine a viable induction agent for the trauma patient with potential brain injury. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(12):1076–1077. doi:10.1136/emermed-2011-200891.

- ↑ Paralysis:Clancy M, Halford S, Walls R, Murphy M. In patients with head injuries who undergo rapid sequence intubation using succinylcholine, does pretreatment with a competitive neuromuscular blocking agent improve outcome? A literature review. Emerg Med J. 2001;18(5):373–375.

- ↑ SAFE Study Investigators, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Australian Red Cross Blood Service, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(9):874–884. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067514.

- ↑ Cooper DJ, Myles PS, McDermott FT, et al. Prehospital hypertonic saline resuscitation of patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1350–1357. doi:10.1001/jama.291.11.1350.

- ↑ Bulger EM, May S, Brasel KJ, et al. Out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation following severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(13):1455–1464. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1405.

- ↑ Sakellaridis N, Pavlou E, Karatzas S, et al. Comparison of mannitol and hypertonic saline in the treatment of severe brain injuries. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(2):545–548. doi:10.3171/2010.5.JNS091685.

- ↑ Kamel H, Navi BB, Nakagawa K, Hemphill JC, Ko NU. Hypertonic saline versus mannitol for the treatment of elevated intracranial pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Critical Care Medicine. 2011;39(3):554–559. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206b9be.

- ↑ Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24 Suppl 1(supplement 1):S1-S106.fulltext

- ↑ Schwarz S et al. Effects of body position on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion in patients with large hemispheric stroke. Stroke. 2002; 33: 497-501

- ↑ Schöchl H, Solomon C, Traintinger S, Nienaber U, Tacacs-Tolnai A, Windhofer C, Bahrami S, Voelckel W: Thromboelastometric (ROTEM) findings in patients suffering from isolated severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011, 28 (10): 2033-2041.

- ↑ Bouma GJ et al. Blood pressure and intracranial pressure-volume dynamics in severe head injury: relationship with cerebral blood flow. J Neurosurg 77:15-19, 1992

- ↑ Rosner MJ et al. Cerebral perfusion pressure management in head injury. J Trauma 30:933-941, 1990

- ↑ Kirkman MA, Smith M. Intracranial pressure monitoring, cerebral perfusion pressure estimation, and ICP/CPP-guided therapy: a standard of care or optional extra after brain injury? Br J Anaesth. 2014 Jan;112(1):35-46.

- ↑ Vespa P. What is the Optimal Threshold for Cerebral Perfusion Pressure Following Traumatic Brain Injury? Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(6).

- ↑ Friess SH et al. Early cerebral perfusion pressure augmentation with phenylephrine after traumatic brain injury may be neuroprotective in a pediatric swine model. Crit Care Med. 2012 Aug;40(8):2400-6.

- ↑ Watts AD et al. Phenylephrine increases cerebral perfusion pressure without increasing intracranial pressure in rabbits with balloon-elevated intracranial pressure. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2002 Jan;14(1):31-4.

- ↑ Friess SH et al. Differing Effects when Using Phenylephrine and Norepinephrine To Augment Cerebral Blood Flow after Traumatic Brain Injury in the Immature Brain. J Neurotrauma. 2015 Feb 15; 32(4): 237–243.

- ↑ Haddad SH and Arabi YM. Critical care management of severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine201220:12.

- ↑ Muizelaar JP, Lutz HA, Becker DP: Effect of mannitol on ICP and CBF and correlation with pressure autoregulation in severely head-injured patients. J Neurosurg. 1984, 61: 700-706.

- ↑ Kamel H, Navi BB, Nakagawa K, Hemphill JC, Ko NU: Hypertonic saline versus mannitol for the treatment of elevated intracranial pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Crit Care Med. 2011, 39 (3): 554-559.

- ↑ Holmes, J. Therapeutic uses of Hypertonic Saline in the Critically Ill Emergency Department Patient. EB Medicine 2013

- ↑ Coles JP, Minhas PS, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, Aigbirihio F, Donovan T, Downey SP, Williams G, Chatfield D, Matthews JC, Gupta AK, Carpenter TA, Clark JC, Pickard JD, Menon DK: Effect of hyperventilation on cerebral blood flow in traumatic head injury: clinical relevance and monitoring correlates. Crit Care Med. 2002, 30 (9): 1950-1959.

- ↑ Stocchetti N et al. Hyperventilation in head injury: a review. Chest. 2005 May;127(5):1812-27.

- ↑ Bullock R, et al: Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007, 24 (Suppl 1): S1-S106.

- ↑ Khan AA, Banerjee A. The role of prophylactic anticonvulsants in moderate to severe head injury. Int J Emerg Med. 2010 Jul 22;3(3):187-91.

- ↑ Thompson K, Pohlmann-Eden B, Campbell LA. Pharmacological treatments for preventing epilepsy following traumatic head injury (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 6. Art. No.: CD009900.

- ↑ Khan AA, Banerjee A. The role of prophylactic anticonvulsants in moderate to severe head injury. Int J Emerg Med. 2010 Jul 22;3(3):187-91.

- ↑ Szaflarski JP et al. Prospective, randomized, single blinded comparative trial of intravenous levetiracetam versus phenytoin for seizure prophylaxis. Neurocrit Care 2010;12:165-172.

- ↑ Schulz-Stübner S: Sedation in traumatic brain injury: avoid etomidate. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33 (11): 2723.

- ↑ Marion DW, Penrod LE, Kelsey SF, et al: Treatment of traumatic brain injury with moderate hypothermia. New Engl J Med. 1997, 336: 540-546.

- ↑ Marion DW: Optimum serum glucose levels for patients with severe traumatic brain injury. F 1000 Med Rep. 2009, 1: 42.

- ↑ Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P, Farrell B, Wasserberg J, Lomas G, Cottingham R, Svoboda P, Brayley N, Mazairac G, Laloë V, Muñoz-Sánchez A, Arango M, Hartzenberg B, Khamis H, Yutthakasemsunt S, Komolafe E, Olldashi F, Yadav Y, Murillo-Cabezas F, Shakur H, Edwards P, CRASH trial collaborators: Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004, 364: 1321-1328.

- ↑ Haddad SH and Arabi YM. Critical care management of severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 2012. 20:12.

- ↑ Kassell NF, Hitchon PW, Gerk MK, Sokoll MD, Hill TR: Alterations in cerebral blood flow, oxygen metabolism, and electrical activity produced by high dose sodium thiopental. Neurosurgery. 1980, 7: 598-603.

- ↑ Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care, AANS/CNS, Carney NA, Ghajar J. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Introduction. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24 Suppl 1:S1–2. doi:10.1089/neu.2007.9997.

- ↑ Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al. Surgical management of acute epidural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3 Suppl):S7–15– discussion Si–iv. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000210361.83548.D0.

- ↑ Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al. Surgical management of acute subdural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3 Suppl):S16–24– discussion Si–iv.

- ↑ Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al. Surgical management of posterior fossa mass lesions. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3 Suppl):S47–55– discussion Si–iv. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000210366.36914.38.

- ↑ Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al. Surgical management of depressed cranial fractures. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3 Suppl):S56–60– discussion Si–iv. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000210367.14043.0E.