Global Disease Detection Stories: Five Steps to Scientific Success in Bangladesh

Writing is hard. Transferring even the simplest ideas from brain to page can be a challenging task. Scientific writing raises the stakes; complex concepts have to be conveyed clearly and precisely.

“Scientific writing is how we participate in the global conversation.”

- Dr. Steve Luby

Despite the difficulties, it’s important to get it right. Good scientific writing is “how we communicate and participate in the global conversation,” says Dr. Stephen Luby, former Country Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Bangladesh. Fortunately, thanks to Steve and his colleagues, strong scientific writing practices have taken root in Bangladesh, helping junior scientists grow and thrive. How do they do it?

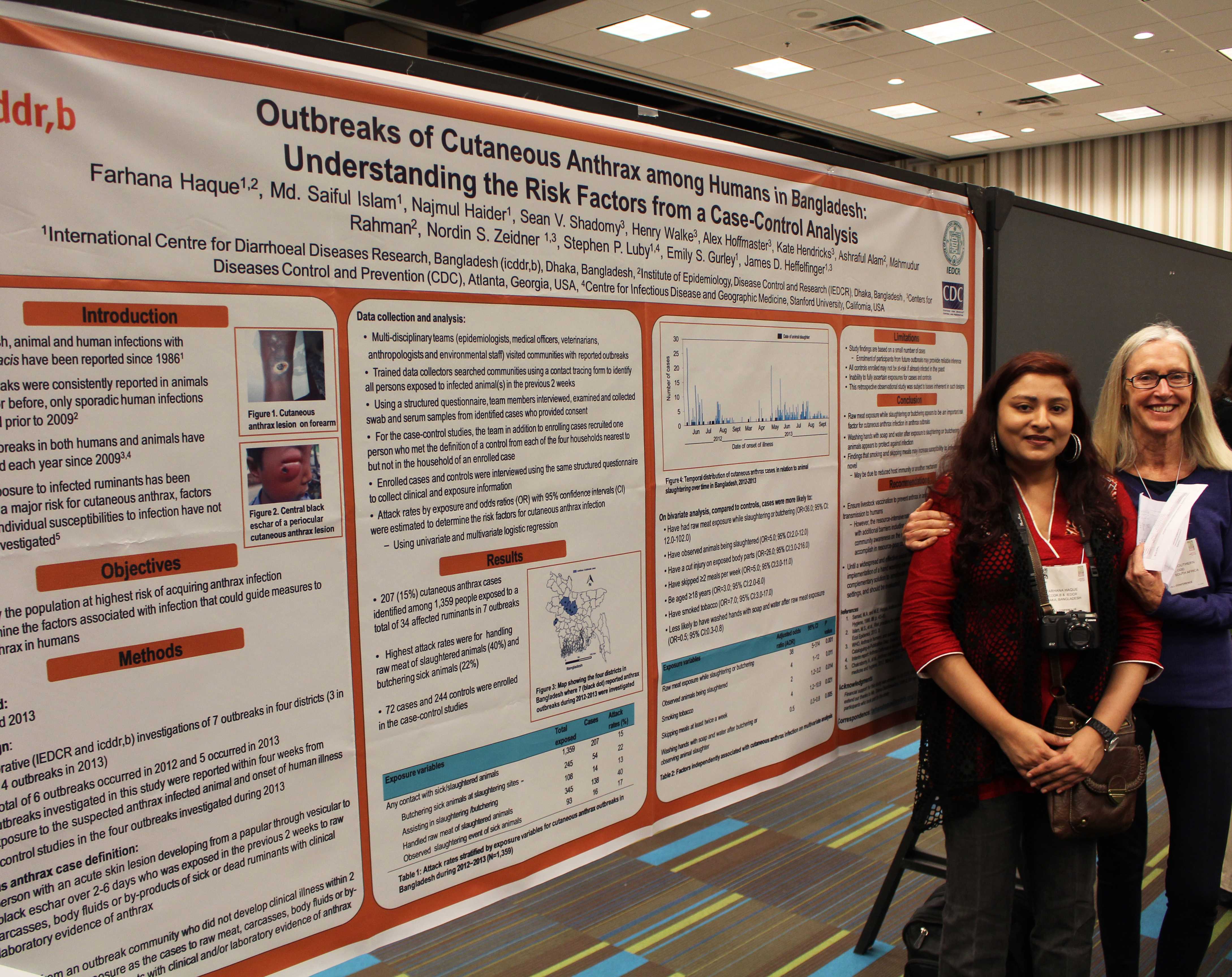

CDC’s Dorothy Southern with Bangladeshi scientist Farhana Haque at the 2015 International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases in Atlanta.

1. Hire people with aptitude

The scientific mentorship program is housed in the Center for Communicable Diseases at icddr,b, an international public health research organization based in Bangladesh. For each entry level research position, the organization can receive up to 300 applications. A rigorous examination screens candidates for their critical thinking and English language skills – every exam is developed from scratch to remove the possibility of cheating. Candidates who pass the examination are then interviewed. This competitive process ensures that only junior scientists with the highest potential are hired.

2. Set expectations

Writing scientific protocols and manuscripts are a prominent part of the job description for everyone hired to conduct research. Retention and promotion depend on productive scientific writing.

3. Provide focused, practical training

Junior scientists have access to a team of writing and statistics coaches. They also must complete a core training package of 12 courses within two years. Participants learn about topics including data analysis, ethics and plagiarism, and how to give effective presentations.

The first training courses were held in 2008 for 11 participants. In 2015, 20 different courses on writing, communications, and statistics are offered to participants in the mentorship program, as well as others in icddr,b who are interested in attending.

4. Structure the writing and feedback experience

Authors, co-authors, and coaches all have clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Authors follow a structured approach for developing manuscripts and tables, beginning with bulleted outlines, which are concise and easier to review than full paragraphs. There is no ghost-authorship, and coaches do not re-write manuscripts. To avoid writing the same critique into multiple manuscripts, Steve developed a “common error” list with explanations of how they should be addressed. While in Bangladesh, Steve collaborated with Dorothy Southern, a scientific writing advisor who edited and organized the list into a systematic guide. The guide is constantly updated and is available to anyone through Stanford University.

Kathy Sturm-Ramirez of CDC Bangladesh explains: “What is unique about this system is that it’s based on a coaching model. We don’t correct their language or arguments. Our comments prompt them to make a stronger argument or highlight the public health value of their paper.”

Diana DiazGranados with Research Investigator Dr. Zaikul Hassan

5. Mentor

Junior scientists receive extensive one-on-one mentoring, meeting with their scientific supervisor to make sure that they stay on track to becoming well-rounded scientists.

Promoting Science Globally

There’s no denying the benefits of solid training in scientific writing. Dr. Najmul Haider, now a PhD student in Denmark, participated in the first Bangladesh trainings in 2008: "Six years later, I have three first-author papers and I just submitted my fourth. I also have seven manuscripts where I am co-author. We didn't even realize how much we were learning. I use those skills every day." In fact, all of the researchers in the first course have produced first-authored manuscripts, and most have now earned their PhD or are working on their doctoral thesis.

Dorothy is now taking this approach on the road: she works with the Global Disease Detection (GDD) Center in South Africa to support scientific writing activities with local partners, as well as with Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) residents throughout the region (including Zambia, Tanzania, and Kenya), and the GDD Center in Thailand. “Scientific writing is crucial for scientific understanding,” says Dorothy about her mission.

Better science leads to better policy

Science conducted locally is relevant to the situation on the ground and can inform public health recommendations and policy. For example, the Bangladesh research team conducted multiple research studies on Nipah virus and discovered that using a barrier while collecting palm sap from trees prevents contamination by bats. They tested this intervention and shared the results with government officials. In response, officials provided guidance to date palm sap harvesters to better protect their product and the health of consumers. Communicating science well enables it to reach more people and fosters better decision-making.

Meanwhile, the scientific writing program is going strong in Bangladesh. According to Diana DiazGranados, head of the Training Support Group at the Center for Communicable Diseases in icddr,b, “The future for scientific writing in Bangladesh is bright. We will continue to provide training and mentoring using a method that we know works. It is a big investment in time and requires a serious commitment to developing independent scientists, but the results are worth it.”

Special thanks to Kevin Russell, Diana DiazGranados, Steve Luby, Dorothy Southern, Katherine Sturm-Ramirez, Najmul Haider, Shua Chai, Zaikul Hassan, Stanford University, GDD Bangladesh and icddr,b.

A new program, Data for Health, will extend training for scientific writing in Bangladesh and improve the strategic use of data for policy, thanks to a partnership between the Bloomberg Foundation and the CDC Foundation. Enhancing Bangladesh’s research and data use capability is a key goal of the GDD Center in Bangladesh, which is part of CDC’s country office. Bangladesh is one of 30 U.S. partner countries named in the Global Health Security Agenda.

- Page last reviewed: December 11, 2015

- Page last updated: December 11, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir