Health Disparities in Cancer

Health disparities refer to differences in health between groups of people. These differences in health may be seen among people of various races and ethnicities, residents of rural areas, women, men, children and adolescents, the elderly, people with disabilities, and the uninsured.

According to CDC’s Office of Minority Health and Health Equity, life expectancy and overall health have improved for most Americans in recent years, but not all Americans have benefited equally. CDC and its partners track trends in cancer incidence (new cancer cases), deaths, and survival (life after a cancer diagnosis) to learn which groups are affected negatively more than others.

Health disparities in cancer can be reduced by expanding access to cancer screening tests, high-quality treatment, and better follow-up after treatment, and by increasing awareness about healthy lifestyle choices that can lower the risk of getting cancer or having cancer come back after it has been treated. Also, social and economic factors which affect health, such as poorer housing and education and lack of transportation, can affect health disparities in cancer.

Breast Cancer

Carletta has lost several family members to cancer, and she knew that put her at higher risk. Knowing her risk helped Carletta catch her breast cancer early.

Carletta has lost several family members to cancer, and she knew that put her at higher risk. Knowing her risk helped Carletta catch her breast cancer early.

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States. Breast cancer deaths are going down the fastest among white women compared to women of other races and ethnicities. African American women have the highest death rate of all racial and ethnic groups and are 40% more likely to die of breast cancer than white women. The reasons for this difference result from many factors, including finding the cancer after it has spread, having more aggressive cancers, treatments that don’t work well, and fewer social and economic resources. To reduce this disparity in deaths, African American women need to be screened as recommended, and get better follow-up care for a mammogram that is not normal.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are two genes that are important to fighting cancer. Sometimes a change occurs in the BRCA genes that prevents them from working normally. This change, or mutation, can raise a person’s risk for breast, ovarian, and other cancers. Some groups are at a higher risk for a BRCA gene mutation than others, including women with Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.

The screening test for breast cancer is a mammogram. Learn about mammography screening recommendations.

Cervical Cancer

Hispanic and African American women have the highest rates of getting and dying from cervical cancer. Getting screened as recommended, starting at age 21, can help prevent cervical cancer or find it early. Getting children vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV), the main cause of cervical cancer, can help prevent them from getting cervical cancer later in life.

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among cancers that affect men and women. African Americans have the highest rates of getting and dying from colorectal cancer when compared to people of other races and ethnicities. Colorectal cancers typically grow slowly, but a person’s risk for colorectal cancer is affected by family and personal health history. It is important to know the signs and symptoms of colorectal cancer.

People with average risk for colorectal cancer should begin screening at age 50. There are several options for screening. Talk to your doctor about screening options and ways to reduce your risk of colorectal cancer.

Liver Cancer

New liver cancer cases and deaths are on the rise in the United States. Americans who are Asian, Pacific Islander, or Hispanic have the highest rates of getting and dying from liver cancer. Many liver cancer cases are related to the hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus. To lower your risk of getting liver cancer, get vaccinated against hepatitis B, get tested for hepatitis C, and avoid drinking too much alcohol.

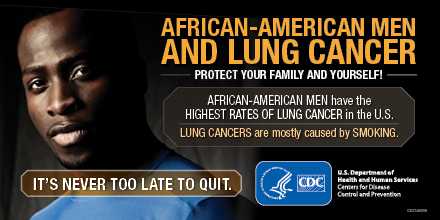

Lung Cancer

African-American men have the highest rates of lung cancer in the U.S. Cigarette smoking is the number one risk factor for lung cancer and other tobacco-related cancers. Using other tobacco products such as cigars or pipes, as well as smoke from other people’s cigarettes, pipes, or cigars (secondhand smoke) also increases the risk for lung cancer.

The most important thing you can do to lower your lung cancer risk is to quit smoking and avoid secondhand smoke. For help quitting, visit smokefree.gov, call 1 (800) QUIT-NOW (784-8669), or text “QUIT” to 47848 from your cell phone.

Not all people who get lung cancer have a history of smoking. It is important to discuss your health history and any symptoms with your doctor to find out if you should be screened.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is more common in African American men and men of African descent. It tends to start at younger ages and grow faster than in other racial or ethnic groups, but medical experts do not know why.

Prostate cancers usually grow slowly. Most men diagnosed with prostate cancer are older than 65 years and do not die from the disease. Finding and treating prostate cancer before symptoms occur may not improve your health or help you live longer. A prostate specific antigen (PSA) test may find prostate cancer at an earlier stage than if you don’t get screened, but many medical groups don’t recommend screening with the PSA test.

Learn about prostate cancer and talk to your doctor before you decide to get tested or treated for prostate cancer.

More Information

- Factors That Contribute to Health Disparities in Cancer

- Cancer Facts for Demographic Groups

- Cancer Among American Indians and Alaska Natives

- AMIGAS

- CDC’s research on health disparities in cancer

- CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report

- Time and distance barriers to mammography facilities in the Atlanta metropolitan area

- Racial disparities in travel time to radiotherapy facilities in the Atlanta metropolitan area

- Years of life and productivity lost from potentially avoidable colorectal cancer deaths in US counties with lower educational attainment (2008-2012)

- Page last reviewed: April 12, 2017

- Page last updated: April 17, 2017

- Content source:

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir