HIV and Injection Drug Use

Fast Facts

- Sharing needles, syringes, and other injection equipment is a direct route of HIV transmission.

- Social and structural factors make it difficult to prevent and treat HIV among people who inject drugs.

- Recent trends in injection drug use have created new prevention challenges.

The risk for getting or transmitting HIV is very high if an HIV-negative person uses injection equipment that someone with HIV has used. This high risk is because the drug materials may have blood in them, and blood can carry HIV. HIV diagnoses among persons who inject drugs (PWID) declined 48% from 2008 to 2014. However, injection drug use (IDU) in nonurban areas has created prevention challenges and has placed new populations at risk for HIV.

The Numbers

HIV and AIDS Diagnosesa

- In 2015, 6% (2,392) of the 39,513 diagnoses of HIV in the United States were attributed to IDU and another 3% (1,202) to male-to-male sexual contactb and IDU.

- Of the HIV diagnoses attributed to IDU in 2015,c 59% (1,412) were among men, and 41% (980) were among women.

- Of the HIV diagnoses attributed to IDU in 2015, 38% (901) were among blacks/African Americans, 40% (951) were among whites, and 19% (443) were among Hispanics/Latinos.d

- If current rates continue, 1 in 23 women who inject drugs and 1 in 36 men who inject drugs will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime.

- Of the 18,303 AIDS diagnoses in 2015, 10% (1,804) were attributed to IDU, and another 4% (761) were attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and IDU.

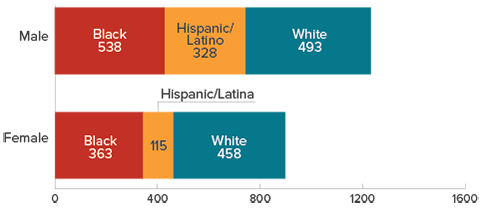

HIV Diagnoses Attributed to Injection Drug Use

by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2015 – United States

*Subpopulations representing 2% or less of the overall US epidemic are not represented in this cart.

Source: CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report 2016;27.

Living With HIV

- At the end of 2013, an estimated 103,100 men in the United States were living with HIV attributed to IDU. Of these, 5% were undiagnosed. An estimated 68,200 women were living with HIV attributed to IDU, and 5% were undiagnosed.

- Among PWID who were diagnosed with HIV in 2014, 82% of males and 83% of females were linked to care within 3 months.e

- Among PWID diagnosed with HIV in 2012 or earlier, 49% of males and 56% of females were retained in HIV care at the end of 2013.e

Prevention Challenges

- The high-risk practices of sharing needles, syringes, and other injection equipment are common among PWID. In a study of cities with high levels of HIV, 40% of new PWID (those who have been injecting for 5 years or less) shared syringes. From 2005 to 2015, syringe sharing declined 34% among black PWID and 12% among Hispanic/Latino PWID, but did not decline among white PWID.

- Risk estimates show that the average chance that an HIV-negative person will get HIV each time that person shares needles to inject drugs with an HIV-positive person is about 1 in 160.

- Injecting drugs can reduce inhibitions and increase sexual risk behaviors, such as having sex without a condom or without medicines to prevent HIV, having sex with multiple partners, or trading sex for money or drugs.

- Studies have found that young PWID (aged <30 years) are at higher risk for HIV than older users because young persons are more likely to share needles and engage in risky sexual behaviors such as sex without a condom or without medicines to prevent HIV.

- The epidemic of prescription opioid misuse and abuse has led to increased numbers of PWID, placing new populations at increased risk for HIV. Nonurban areas with limited HIV prevention and treatment services and substance use disorder treatment services, traditionally areas at low risk for HIV, have been disproportionately affected.

- Social and economic factors limit access to HIV prevention and treatment services among PWID. In a study of cities with high levels of HIV, more than half (51%) of HIV-positive PWID reported being homeless, 30% reported being incarcerated, and 20% reported having no health insurance in the last 12 months.

- Stigma and discrimination are associated with illicit substance use. Often, IDU is viewed as a criminal activity rather than a medical issue that requires counseling and rehabilitation. Stigma and mistrust of the health care system may prevent PWID from seeking HIV testing, care, and treatment.

- IDU can cause other diseases and complications. In addition to being at risk for HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) such as viral hepatitis, PWID can get other serious health problems, like skin infections, abscesses, or even infections of the heart. People can overdose and get very sick or even die from IDU.

What CDC Is Doing

CDC and its partners are pursuing a high-impact prevention approach to advance the goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, updated to 2020, to maximize the effectiveness of current HIV prevention methods, and to increase what we know about the behaviors of PWID and the risks they face. For example, CDC

- Has awarded at least $330 million each year, starting in 2012 ($343.7 million in 2015), to health departments to direct resources to the populations and geographic areas of greatest need, including PWID, and prioritize the HIV prevention strategies that will have the greatest impact.

- Supports intervention programs that deliver services to PWID such as Community PROMISE, a community-level HIV/STD prevention program for populations at high risk that uses role-model stories and peer advocates to distribute prevention materials within social networks.

- Provides guidance about which syringe services program (SSP) activities can be supported with CDC funds and how CDC-funded programs may request to direct resources to implement new or expand existing SSPs. SSPs can play a role in preventing HIV and other health problems among PWID. SSPs provide access to sterile syringes and ideally provide other comprehensive services such as help with stopping substance misuse; testing and linkage to treatment for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C; and other prevention services.

- Supports responses for outbreaks of HIV traced to injection drug use such as the 2015 outbreak in rural Indiana.

- Supports programs to deliver biomedical approaches to HIV prevention and treatment for PWID such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for people at high risk, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to lower the chances of becoming infected after an exposure, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) or daily medicines to treat HIV.

- Maintains the National HIV Surveillance System to monitor and evaluate HIV and AIDS trends among various populations, including PWID. Data are collected through state and local health departments about HIV and AIDS cases and then reported to CDC after personal identifiers have been removed. These data may be used to determine who is most at-risk and to develop and implement interventions that reach PWID.

- Conducts the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance survey every three years to examine behaviors of PWID in jurisdictions with high HIV prevalence, including risk behaviors, testing behaviors, and use of HIV prevention services.

- Provides culturally appropriate prevention messages through Act Against AIDS, a national initiative that focuses on raising awareness, fighting stigma, and reducing the risk of HIV infection among at-risk populations, including PWID.

a HIV and AIDS diagnoses indicate when a person is diagnosed with HIV or AIDS, not when the person was infected.

b The term male-to-male sexual contact is used in CDC surveillance systems to indicate a behavior that transmits HIV infection, not how individuals self-identify in terms of their sexuality.

c Unless otherwise indicated, the numbers include infections attributed to IDU only, not those attributed to IDU and male-to-male sexual contact.

d Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

e Based on 32 states and the District of Columbia (the areas with complete lab reporting by December 2015).

Injection Drug Use Data

CDC’S National HIV Surveillance System is the primary source for monitoring HIV trends in the United States. It combines information on characteristics, utilization of care services, disease progression, and behaviors of people diagnosed with HIV infection. CDC funds and assists state and local health departments to collect the information and report data to CDC after personal identifiers are removed. Information from around the country can be analyzed to determine who is being affected and is essential for monitoring whether people are receiving the vital HIV medical care services they need to live long, healthy lives and reduce transmission to others. Data from NHSS on HIV infection among persons who inject drugs is disseminated through national HIV/AIDS surveillance reports, surveillance slide sets, the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Tuberculosis Prevention (NCHHSTP) Atlas , and other sources for a wide range of uses at the federal, state, and local levels.

CDC conducted a meta-analysis of behavioral data from national surveys to estimate the number of persons in the U.S. who have injected drugs to use as a denominator to calculate HIV diagnosis and prevalence rates for IDU. National estimates of population sizes can be used to provide a broader understanding of the HIV epidemic among those at risk for transmission and acquisition of HIV. These estimates and disease rate calculations also provide important tools for monitoring and characterizing the HIV epidemic in the United States as well as planning and optimizing the allocation of resources to programs serving disproportionately affected populations and addressing health inequities.

Bibliography

- CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report 2016;27.

- CDC. HIV and Injection Drug Use: Syringe Services Programs for HIV Prevention. Vital Signs. December 2016.

- CDC. HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs—national HIV behavioral surveillance: injection drug use, 20 U.S. cities, 2012. HIV Surveillance Special Report;15. Revised edition.

- Semaan S, Des Jarlais, Malow R. Behavior change and health-related interventions for heterosexual risk reduction among drug users. Subst Use Misuse 2006;40(10-12):1349-78. PubMed abstract.

- Broz D, Pham H, Spiller M, Wejnert C, Le B, Neaigus A, Paz-Bailey G. Prevalence of HIV infection and risk behaviors among younger and older injecting drug users in the United States, 2009. AIDS Behav 2014;18(3) Supplement:284-96. PubMed abstract.

- Rondinelli AJ, Ouellet LJ, Strathdee SA, Latka MH, Hudson SM, Hagan H, et al. Young adult injection drug users in the United States continue to practice HIV risk behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;104(1-2):167-74. PubMed abstract.

- Wagner KD, Lankenau SE, Palinkas LA, Richardson JL, Chou CP, Unger JB. The perceived consequences of safer injection: an exploration of qualitative findings and gender differences. Psychol Health Med 2010;15(5):560-73. PubMed abstract.

- CDC. Recommendations for HIV prevention with adults and adolescents with HIV in the United States, 2014.

- CDC. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV – United States, 2016.

- Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection among people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok tenofovir study): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381(9883):2083-90. PubMed abstract.

- US Public Health Service. PreExposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States – a clinical practice guideline, 2014.

- CDC. Community outbreak of HIV infection linked to injection drug use of Oxymorphone — Indiana, 2015. MMWR 64(16);443-44.

Other Resources

Related Resources

- HIV And Injecting Drugs 101 Consumer Info Sheet

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

- Vital Signs: HIV and Injection Drug Use

- CDC Act Against AIDS Campaigns

- Injury Prevention & Control: Prescription Drug Overdose

- HIV and Substance Use in the United States

General Resources

- CDC-INFO 1-800-CDC-INFO (232-4636)

- CDC HIV Website

- CDC Act Against AIDS Campaign

- CDC HIV Risk Reduction Tool (BETA)

- Page last reviewed: March 16, 2017

- Page last updated: March 16, 2017

- Content source: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir