HIV Among African American Gay and Bisexual Men

Fast Facts

- Black/African Americana gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with menb account for more US HIV diagnoses than any other group.

- The estimated number of annual HIV infections remained stable among African American gay and bisexual men from 2010 to 2014.

- Though HIV rates are high among African American gay and bisexual men, there are more tools than ever before to prevent HIV.

African American gay and bisexual men are more affected by HIV than any other group in the United States. More than 10,000 African American gay and bisexual men received an HIV diagnosis in 2015.

The Numbers

HIV Infectionsc

From 2010 to 2014, estimated annual HIV infections remained stable among African American gay and bisexual men, at about 10,000 per year.

HIV Diagnosesd

In 2015:

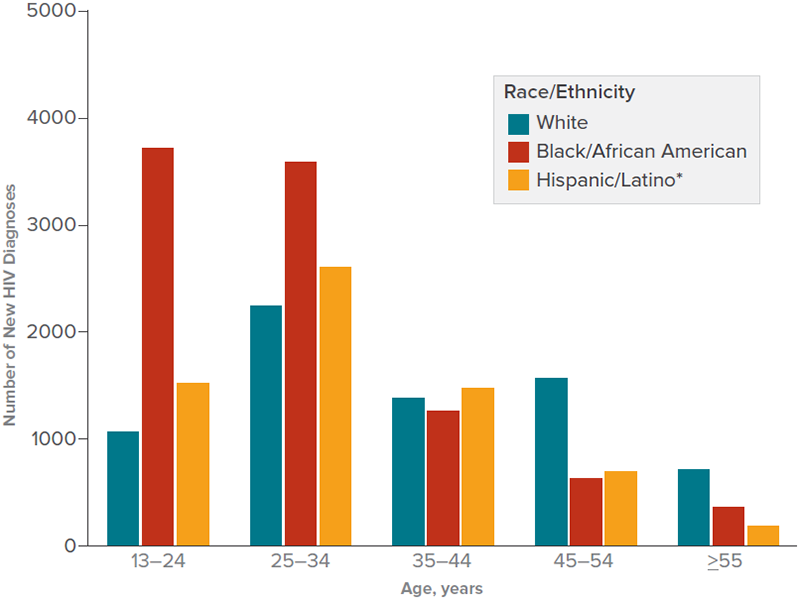

- Among all gay and bisexual men who received an HIV diagnosis in the United States, African Americans accounted for the highest number (10,315; 39%), followed by whites (7,570; 29%) and Hispanics/Latinose (7,013; 27%).f

- 38% (3,888) of African American gay and bisexual men who received an HIV diagnosis were aged 13-24. Thirty-seven percent (3,843) were aged 25-34; 13% (1,305) were aged 35-44; 8% (872) were aged 45-54; and 4% (405) were aged 55 or older.

Between 2010 and 2014:

- After years of increases, HIV diagnoses among African American gay and bisexual men stabilized, increasing less than 1%.

- HIV diagnoses among young African American gay and bisexual men (aged 13 to 24) declined 2%.

Living With HIV and Deaths

- At the end of 2014, an estimated 615,400 gay and bisexual men were living with HIV (56% of everyone living with HIV in the United States). African Americans accounted for 32% of gay and bisexual men living with HIV.

- In 2014, an estimated 20% of African American gay and bisexual men living with HIV did not know they had the virus. But that percentage has declined since 2010, when 24% were unaware of their infection.

- Among all African American gay and bisexual men who received an HIV diagnosis in 2015, 69% were linked to HIV medical care within 1 month.g

- Among all African American gay and bisexual men who received an HIV diagnosis in 2013 or earlier, 71% received HIV medical care in 2014, 54% received continuous HIV care, and 52% had a suppressed viral load.h

- In 2014, there were 1,938 deaths among African American gay and bisexual men living with diagnosed HIV infection.i

HIV Diagnoses Among Men Who Have Sex With Men, by Race/Ethnicity and Age at Diagnosis, 2015—United States

Prevention Challenges

Stigma, homophobia, and discrimination put gay and bisexual men of all races/ethnicities at risk for multiple physical and mental health problems and may affect whether they seek and are able to receive high-quality health services, including HIV testing, treatment, and other prevention services. In addition to stigma and other risk factors affecting all gay and bisexual men (a larger percentage of men with HIV in sexual networks; a significant proportion of the population engaging in receptive anal sex, or “bottoming,” which is the riskiest sexual behavior for getting HIV; more sex partners compared to other men), several factors are specific to African American gay and bisexual men. These include:

- Smaller and more exclusive sexual networks. African American gay and bisexual men are a small subset of all gay and bisexual men, and their partners tend to be of the same race. Because of the small population size and the higher prevalence of HIV in that population relative to other races/ethnicities, African American gay and bisexual men are at greater risk of being exposed to HIV within their sexual networks.

- Lack of awareness of HIV status. Among African American gay and bisexual men who have HIV, a lower percentage know their HIV status compared to HIV-positive gay and bisexual men of some other races/ethnicities.j People who do not know they have HIV cannot take advantage of HIV care and treatment and may unknowingly pass HIV to others.

- Socioeconomic factors. Having limited access to quality health care, lower income and educational levels, and higher rates of unemployment and incarceration may place some African American gay and bisexual men at higher risk for HIV than men of some other races/ethnicities.

What CDC Is Doing

CDC funds state and local health departments and community-based organizations (CBOs) to deliver effective HIV prevention services for African American gay and bisexual men. Some of CDC’s activities include:

- Under the current funding opportunity, CDC has awarded at least $330 million per year to health departments to direct resources to the populations and geographic areas of greatest need and prioritize the HIV prevention strategies that will have the greatest impact. A new notice of funding opportunity (NOFO) will begin in 2018.

- In 2017, CDC awarded nearly $11 million per year for 5 years to 30 CBOs to provide HIV testing to young gay and bisexual men of color and transgender youth of color, with the goals of identifying undiagnosed HIV infections and linking those who have HIV to care and prevention services.

- In 2015, CDC added three new NOFOs to help health departments reduce HIV infections and improve HIV medical care among gay and bisexual men.

- Targeted Highly-Effective Interventions to Reverse the HIV Epidemic (THRIVE) supports state and local health department demonstration projects to develop community collaborations that provide comprehensive HIV prevention and care services for MSM of color.

- Training and Technical Assistance for THRIVE strengthens the capacity of funded health departments and their collaborative partners to plan, implement, and sustain (through ongoing engagement, assessment, linkage, and retention) comprehensive prevention, care, behavioral health, and social services models for MSM of color at risk for and living with HIV infection.

- Project PrIDE (PrEP, Implementation, Data2Care, and Evaluation) supports 12 health departments in implementing PrEP and Data to Care demonstration projects for to gay and bisexual men of color.

- The Capacity Building Assistance for High-Impact HIV Prevention, a national program that provides training and technical assistance for health departments, CBOs, and health care organizations to help them better address gaps in the HIV continuum of care and provide high-impact prevention for people at high risk for HIV.

Through its Act Against AIDS campaigns and partnerships, CDC provides African American gay and bisexual men with effective and culturally appropriate messages about HIV prevention and treatment. For example,

- Start Talking. Stop HIV. helps gay and bisexual men communicate about safer sex, testing, and other HIV prevention issues.

- Doing It, a national HIV testing and prevention campaign, encourages all adults to know their HIV status and protect themselves and their community by making HIV testing a part of their regular health routine.

- HIV Treatment Works shows how people living with HIV have overcome barriers to stay in care and provides resources on how to live well with HIV.

- Partnering and Communicating Together (PACT) to Act Against AIDS, a 5-year partnership with organizations such as the National Black Justice Coalition and the Black Men’s Xchange, is raising awareness about testing, prevention, and retention in care among populations disproportionately affected by HIV, including African American gay and bisexual men.

To learn more about health issues affecting gay and bisexual men, visit the CDC Gay and Bisexual Men’s Health site.

a Referred to as African American in this fact sheet.

b The term male-to-male sexual contact is used in CDC surveillance systems. It indicates a behavior that transmits HIV infection, not how individuals self-identify in terms of their sexuality. This fact sheet uses the term gay and bisexual men.

cEstimated annual HIV infections are the estimated number of new infections (HIV incidence) that occurred in a particular year, regardless of when those infections were diagnosed.

dHIV diagnoses refers to the number of people diagnosed with HIV infection during a given time period, not when the people were infected.

e Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

f The numbers reported in this fact sheet include infections attributed to male-to-male sexual contact only, not those attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use.

g In 37 states and the District of Columbia (the areas with complete lab reporting by December 2016).

h Viral suppression is defined as having fewer than 200 copies of the virus per milliliter of blood on the most recent viral load test in 2014. Receiving continuous HIV care is defined as having two viral load or CD4 tests 3 or more months apart in 2014. (CD4 cells are the cells in the body’s immune system that are destroyed by HIV.)

i Deaths may be due to any cause.

j Though African American gay and bisexual men report higher HIV testing in the past year than Hispanic/Latino or white gay and bisexual men, they also have a higher prevalence of HIV. That means a greater proportion of those who have not been tested recently are HIV-positive.

Bibliography

- CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report 2016:27.

- CDC. High-impact HIV prevention: CDC’s approach to reducing HIV infections in the United States. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- CDC. HIV incidence: Estimated annual infections in the U.S., 2008-2014 [fact sheet]. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- CDC. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 U.S. cities, 2014. HIV Surveillance Special Report 2016;15.

- HIV testing experience before HIV diagnosis among men who have sex with men—21 Jurisdictions, United States, 2007–2013. MMWR 2016;65(37):999-1003.

- CDC. Lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis [press release]. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- CDC. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2017;22(2).

- CDC. New HIV infections drop 18 percent in six years [press release]. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- CDC. Progress along the continuum of HIV care among blacks with diagnosed HIV—United States, 2010. MMWR 2014;63(5):85-9.

- CDC. Trends in U.S. HIV diagnoses, 2005-2014 [fact sheet]. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- Kwan CK, Rose CE, Brooks JT, Marks G, Sionean C. HIV testing among men at risk for acquiring HIV infection before and after the 2006 CDC recommendations. Public Health Rep 2016;131(2):311-9. PubMed abstract.

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;380(9839):341-8. PubMed abstract.

- CDC. HIV care outcomes among men who have sex with men with diagnosed HIV infection—United States, 2015. MMWR 2017;66(37):969-74.

Fact Sheets

Other Resources

Web Sites

- Gay and Bisexual Men’s Health

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health

- Positive Spin

- National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

General Resources

- CDC-INFO 1-800-CDC-INFO (232-4636)

- CDC HIV Website

- CDC Act Against AIDS Campaign

- CDC HIV Risk Reduction Tool (BETA)

- Page last reviewed: September 27, 2017

- Page last updated: September 27, 2017

- Content source: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir